The Casual Revolution Of... 1987 Making Adventure Games Accessible to the Masses

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tiadventureland-Manual

Texas Instruments Home Computer ADVENTURE Overview Author: Adventure International Language: TI BASIC Hardware: TI Home Computer TI Disk Drive Controller and Disk Memory Drive or cassette tape recorder Adventure Solid State Software™ Command Module Media: Diskette and Cassette Have you ever wanted to discover the treasures hidden in an ancient pyramid, encounter ghosts in an Old West ghost town, or visit an ancient civilization on the edge of the galaxy? Developed for Texas Instruments Incorporated by Adventure International, the Adventure game series lets you e xperience these and many other adventures in the comfort of your own home. To play any of the Adventure games, you need both the Adventure Command Module (sold separately) and a cassette- or diskette based Adventure game. The module contains the general program instructions which are customized by the particular cassette tape or diskette game you use with it. Each game in the series is designed to challenge your powers of logical reasoning and may take hours, days, or even weeks to complete. However, you can leave a game and continue it at another time by saving your current adventure on a cassette tape or diskette. Copyright© 1981, Texas Instruments Incorporated. Program and database contents copyright © 1981, Adventure International and Texas Instruments Incorporated. Page l Texas Instruments ADVENTURE Description ADVENTURE Description A variety of adventure games are available on cassette tape or Pyramid of Doom diskette from your local dealer or Adventure International. To give you an idea of the exciting and interesting games you can The Pyramid of Doom adventure starts in a desert near a pool of play, a brief summary of the currently available adventures is liquid, with a pole sticking out of the sand. -

Penser La Formation Et Les Évolutions Du Jeu Sur Support Numérique Sébastien Genvo

Penser la formation et les évolutions du jeu sur support numérique Sébastien Genvo To cite this version: Sébastien Genvo. Penser la formation et les évolutions du jeu sur support numérique. Sciences de l’information et de la communication. Université de Lorraine, 2013. tel-02169832 HAL Id: tel-02169832 https://hal.univ-lorraine.fr/tel-02169832 Submitted on 1 Jul 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. UNIVERSITÉ DE LORRAINE Centre de recherche sur les médiations (ÉA 3476) Mémoire pour l’habilitation à diriger des recherches en sciences de l’information et de la communication TOME 1 PENSER LA FORMATION ET LES ÉVOLUTIONS DU JEU SUR SUPPORT NUMÉRIQUE Présenté et soutenu publiquement le cinq décembre 2013 par Sébastien Genvo Garant : M. Jacques Walter, Professeur à l’université de Lorraine Jury M. Jean-Jacques Boutaud, Professeur à l’université de Bourgogne M. Gilles Brougère, Professeur à l’université Paris Nord Mme Sylvie Leleu-Merviel, Professeure à l’université de Valenciennes et du Hainaut-Cambrésis M. Bernard Perron, Professeur titulaire à l’université de Montréal Mme Brigitte Simonnot, Professeure à l’université de Lorraine Sommaire Introduction .......................................................................................... -

Accolade-Catalog2

Introduction • • Jack Nicklaus Golf & Course • Design: Signature Edition'" • AI Michaels Announces ~ • HardBall III'" • T • Road & Track®Presents Grand Prix Unlimited'" • • Science Fiction Role-Playing: • Star Control II'" • ® SNOOPY's Game Club'" • • Accolade in Motion • • Sports: Mike Ditka Ultimate • Footbalr & Winter Challenge • • Driving: A Test Drive III: The Passion'" 1 L 0 Role Playing: Elvira®Mistress (J • of the Dark'" & Elvira II the ~ • Jaws of Cerberus'" Graphic Adventure: Les Manley in: Lost in LA'" Science Fiction: Hoverforce'" & Star Contror o Ordering Information Macintosh Titles All Time Favorites Product Availability s 1 Accolade In Motion •••••• From the moment hen it comes to entertainment software, you'll find a game IS Accolade in motion creating the finest and most conceived imaginative computer games on the market today. through design, Whether your favorite genre is sports, driving, role-playing, science fiction or graphic adventure, Accolade has a great ... production, game for you. and meticulous From the soaring drives of Jack Nicklaus to the towering home testing, we runs of HardBall 111- from the blazingly fast Formula One work hard to cars of Grand Prix Unlimited to the white-hot space combat of Star Control 11- Accolade pours on the excitement. produce the We pour out our hearts, too, with children's games like our very finest warm and funny SNOOPY's Game Club. games Accolade is proud that so many of the titles in our constantly possible. growing library have won critical acclaim for their realistic simulations, graphic excellence and absorbing gameplay. Yet it is our minds in motion - the creativity and dedication of our Accolade staff - that is our greatest pride. -

Case History

Page 1 of 15 Case History: Yinjie Soon STS 145, Winter 2002 Page 2 of 15 Yinjie Soon STS145: History of Computer Game Design Final Paper 12 February 2002 Case History Star Control II: The Ur-Quan Masters In July 1990, the two partners who formed the software company Toys for Bob released their first game, Star Control, under game publisher Accolade for the personal computer system. These two men – Paul Reiche III and Fred Ford – were big fans of science fiction, and in Reiche’s case, fantasy role playing games (especially Dungeons and Dragons). Unsurprisingly, the game had a strong science fiction theme and heavy doses of traditional role-playing elements, wherein the player controlled one of two sides in an effort to either take over the universe as the marauding conquerors of the Ur-Quan Hierarchy, or save the universe as the brave defenders of the Alliance of Free Stars. Star Control effectively interleaved elements of strategy and action; the player tried to outwit the opposing forces in various turn-based inter-planetary strategic scenarios, and subsequently engaged enemy ships in real-time “space melee” one-on-one spaceship dogfights, similar in style to Spacewar, the earliest of video games (Derrenbacker). Many of the sequel’s most interesting elements, such as the unique characteristics of each race’s ships and behaviors, were established in this game and would carry on to Star Control 2. Figures 1a and 1b show some scenes from Star Control, illustrating how advanced some of the graphics from the game were for the time (figure 1a is also an early manifestation of the creators’ sense of humor – the ship shown in the middle of the picture is the flagship of an all-female race of humanoids; the explanation behind the visual is left to the reader’s imagination.). -

![[Japan] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1000 Miglia](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3367/japan-sala-giochi-arcade-1000-miglia-393367.webp)

[Japan] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1000 Miglia

SCHEDA NEW PLATINUM PI4 EDITION La seguente lista elenca la maggior parte dei titoli emulati dalla scheda NEW PLATINUM Pi4 (20.000). - I giochi per computer (Amiga, Commodore, Pc, etc) richiedono una tastiera per computer e talvolta un mouse USB da collegare alla console (in quanto tali sistemi funzionavano con mouse e tastiera). - I giochi che richiedono spinner (es. Arkanoid), volanti (giochi di corse), pistole (es. Duck Hunt) potrebbero non essere controllabili con joystick, ma richiedono periferiche ad hoc, al momento non configurabili. - I giochi che richiedono controller analogici (Playstation, Nintendo 64, etc etc) potrebbero non essere controllabili con plance a levetta singola, ma richiedono, appunto, un joypad con analogici (venduto separatamente). - Questo elenco è relativo alla scheda NEW PLATINUM EDITION basata su Raspberry Pi4. - Gli emulatori di sistemi 3D (Playstation, Nintendo64, Dreamcast) e PC (Amiga, Commodore) sono presenti SOLO nella NEW PLATINUM Pi4 e non sulle versioni Pi3 Plus e Gold. - Gli emulatori Atomiswave, Sega Naomi (Virtua Tennis, Virtua Striker, etc.) sono presenti SOLO nelle schede Pi4. - La versione PLUS Pi3B+ emula solo 550 titoli ARCADE, generati casualmente al momento dell'acquisto e non modificabile. Ultimo aggiornamento 2 Settembre 2020 NOME GIOCO EMULATORE 005 SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1 On 1 Government [Japan] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1000 Miglia: Great 1000 Miles Rally SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 10-Yard Fight SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 18 Holes Pro Golf SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1941: Counter Attack SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1942 SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1943 Kai: Midway Kaisen SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1943: The Battle of Midway [Europe] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1944 : The Loop Master [USA] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1945k III SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 19XX : The War Against Destiny [USA] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 2 On 2 Open Ice Challenge SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 4-D Warriors SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 64th. -

Explore a Change of Perspective in Virtual Reality

Rim: Explore a Change of Perspective in Virtual Reality Thesis Presented by Jiayu Liu to The College of Arts, Media and Design In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Game Science and Design Northeastern University Boston, Massachusetts December 2017 1 Rim: Explore a Change of Perspective in Virtual Reality by Jiayu Liu ABSTRACT Player perspective is a vital and rudimentary component of game design. Perspective defines points of view (POV) and what the player as a particular character can both see and interact with. Perspective can greatly affect player agency in making decisions and getting feedback from the game world. However, the change in perspective and character embodiment as a part of player agency is rarely explored in video games. In the paper, Rim is introduced as an adventure spatial puzzle game in VR which uses the core mechanic of changing perspective as the principal form of player agency. 2 1. Introduction Player perspective is a vital and rudimentary component of game design. Perspective defines points of view (POV) and what the player as a particular character can both see and interact with. POVs convey visual information in distinctive ways that lead to a myriad of possibilities to perceiving and engaging with the game world [2]. However, despite its expressive capabilities, the option to change perspective and character representation during gameplay, with a few exceptions, is rare in video games. In some cases, changes of perspective take place in preset cinematic sequences and functionalities such as zooming-in/-out and rotating camera [5]. -

Thf SO~Twarf Toolworks®Catalog SOFTWARE for FUN & INFORMATION

THf SO~TWARf TOOlWORKS®CATAlOG SOFTWARE FOR FUN & INFORMATION ORDER TOLL FREE 1•800•234•3088 moni tors each lesson and builds a seri es of personalized exercises just fo r yo u. And by THE MIRACLE PAGE 2 borrowi ng the fun of vid eo ga mes, it Expand yo ur repertoire ! IT'S AMIRAClf ! makes kids (even grown-up kids) want to The JI!/ irac/e So11g PAGE 4 NINT!NDO THE MIRACLE PIANO TEACHING SYSTEM learn . It doesn't matter whether you 're 6 Coflectioll: Vo/11111e I ~ or 96 - The Mirttcle brings th e joy of music adds 40 popular ENT!RTA INMENT PAGE/ to everyo ne. ,.-~.--. titles to your The Miracle PiC1110 PRODUCTI VITY PAGE 10 Tet1dti11gSyste111, in cluding: "La Bamba," by Ri chi e Valens; INFORMATION PAGElJ "Sara," by Stevie Nicks; and "Thi s Masquerade," by Leon Russell. Volume II VA LU EP ACKS PAGE 16 adds 40 MORE titles, including: "Eleanor Rigby," by John Lennon and Paul McCartney; "Faith," by George M ichael; Learn at your own pace, and at "The Girl Is M in e," by Michael Jackson; your own level. THESE SYMBOLS INDICATE and "People Get Ready," by C urtis FORMAT AVAILABILITY: As a stand-alone instrument, The M irt1de Mayfield. Each song includes two levels of play - and learn - at yo ur own rivals the music industry's most sophis playin g difficulty and is full y arra nged pace, at your own level, NIN TEN DO ti cated MIDI consoles, with over 128 with complete accompaniments for a truly ENTERTAINMENT SYST!M whenever yo u want. -

Lucasarts and the Design of Successful Adventure Games

LucasArts and the Design of Successful Adventure Games: The True Secret of Monkey Island by Cameron Warren 5056794 for STS 145 Winter 2003 March 18, 2003 2 The history of computer adventure gaming is a long one, dating back to the first visits of Will Crowther to the Mammoth Caves back in the 1960s and 1970s (Jerz). How then did a wannabe pirate with a preposterous name manage to hijack the original computer game genre, starring in some of the most memorable adventures ever to grace the personal computer? Is it the yearning of game players to participate in swashbuckling adventures? The allure of life as a pirate? A craving to be on the high seas? Strangely enough, the Monkey Island series of games by LucasArts satisfies none of these desires; it manages to keep the attention of gamers through an admirable mix of humorous dialogue and inventive puzzles. The strength of this formula has allowed the Monkey Island series, along with the other varied adventure game offerings from LucasArts, to remain a viable alternative in a computer game marketplace increasingly filled with big- budget first-person shooters and real-time strategy games. Indeed, the LucasArts adventure games are the last stronghold of adventure gaming in America. What has allowed LucasArts to create games that continue to be successful in a genre that has floundered so much in recent years? The solution to this problem is found through examining the history of Monkey Island. LucasArts’ secret to success is the combination of tradition and evolution. With each successive title, Monkey Island has made significant strides in technology, while at the same time staying true to a basic gameplay formula. -

Sega Enterprises LTD. V. Accolade, Inc.: What's So Fair About Reverse Engineering?

Loyola of Los Angeles Entertainment Law Review Volume 14 Number 3 Article 3 3-1-1994 Sega Enterprises LTD. v. Accolade, Inc.: What's so Fair about Reverse Engineering? David C. MacCulloch Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/elr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation David C. MacCulloch, Sega Enterprises LTD. v. Accolade, Inc.: What's so Fair about Reverse Engineering?, 14 Loy. L.A. Ent. L. Rev. 465 (1994). Available at: https://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/elr/vol14/iss3/3 This Notes and Comments is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews at Digital Commons @ Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Loyola of Los Angeles Entertainment Law Review by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NOTES SEGA ENTERPRISES LTD. v. ACCOLADE, INC.: WHAT'S SO FAIR ABOUT REVERSE ENGINEERING? I. INTRODUCTION You are the president of a major corporation that develops and distributes computer video game cartridges and the consoles on which the games can be played. Your company has maintained a majority of the market share by remaining at the forefront of the game cartridges field. Your company's ability to be the first to incorporate all the latest enhance- ments is due to the efforts of one man-your chief designer of game concepts. If he were to leave, your company's position as number one in the industry would be jeopardized. One day, your chief designer demands that if he is not made an executive vice-president and equity shareholder in the company he will resign and take with him a new concept he has been privately developing at home that will take video game technology to the next level. -

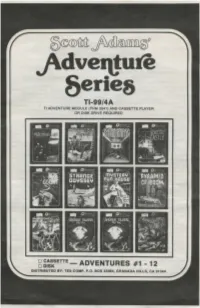

J\Dveqtute Series Tl-99/4A TI ADVENTURE MODULE (PHM 3041) and CASSETIE PLAYER OR DISK DRIVE REQUIRED SCOTT ADAMS' ADVENTURE by Scott Adams INSTRUCTIONS TEX•COMP- P.O

®~@lilt ftcdl®mID~0 j\dveqtute Series Tl-99/4A TI ADVENTURE MODULE (PHM 3041) AND CASSETIE PLAYER OR DISK DRIVE REQUIRED SCOTT ADAMS' ADVENTURE by Scott Adams INSTRUCTIONS TEX•COMP- P.o. Box 33089 • Granada Hills, CA 91344 (818) 366-6631 ADVENTURE Overview CopyrightC1981 by Adventure International, Texas Instruments, Inc. Cl 985 TEX-COMP TI Users Supply Company All rights reserved Printed with permission ADVENTURES by Scott Adams Author: Adventure International AN OVERVIEW How do you know which objects you need? Trial and er Language: TI Basic I stood at the bottom of a deep chasm. Cool air sliding ror, logic and imagination. Each time you try some action, down the sides of the crevasse hit waves of heat rising you learn a little more about the game. Hardware: TI Home Computer from a stream of bubbling lava and formed a mist over the Which brings us to the term "game" again. While called sluggish flow. Through the swrlling clouds I caught games, Adventures are actually puzzles because you have to TI Disk Drive Controller and Disk Memory Drive or glimpses of two ledges high above me: one was bricked, discover which way the pieces (actions, manipulations, use cassette tape recorder the other appeared to lead to the throne room I had been of magic words, etc.) lit together in order to gather your seeking. treasures or accomplish the mission. Like a puzzle, there are Adventure Solld State Software™ Command Module A blast of fresh air cleared the mist near my feet and a number of ways to fit the pieces together; players who like a single gravestone a broken sign appeared momen have found and stored ail the treasures (there are 13) of Ad Media: Diskette and Cassette tarily. -

Organization of Computer Programs Organization of Computer Programs

Organization of Computer Programs Organization of Computer Programs Hardware Organization of Computer Programs Operating System Hardware Organization of Computer Programs Application Application Program Program Operating System Hardware Interoperability Application Application Program Program Operating System Hardware Interoperability Application Application Program Program Operating System Hardware Interoperability Strategy #1 (e.g., Microsoft, Apple) Borland Microsoft Free access Microsoft Dell Interoperability Strategy #2 (e.g., Sega, Nintendo) Licensee Nintendo License fees Nintendo Nintendo Interoperability Strategy #3 (e.g., MAI Systems Corp.) MAI MAI No licenses MAI MAI Sega (CA9 1992) Licensed Sega Games Games License fees TMSS Sega Genesis III Sega (CA9 1992) Licensed Sega Games Games Accolade Games License fees TMSS Lock-out Sega Genesis III Sega (CA9 1992) Microcode (copied by Accolade) Licensed Sega Games Games Accolade Games License fees TMSS Lock-out Sega Genesis III Sega (CA9 1992) Licensed Sega Games Games Accolade Games License fees TMSS TMSS initialization Lock-out code Sega Genesis III Sega (CA9 1992) Licensed Sega Games Games Accolade Games License fees TMSS Sega Genesis III Reverse Engineering for Interoperability • Courts finding this to be fair use: – CAFC (Atari 1992 [dictum]; Bowers 2003 [dictum]) – CA5 (DSC Communications 1996) – CA 9 (Sega 1992; Sony 2000) – CA11 (Bateman 1996) • EC Directive 91/250, Art. 6, takes same position Fair Use Doctrine • Purpose and Character of the Use – commercial use – transformative uses – parody – propriety of defendant’s conduct • Nature of the Copyrighted Work – fictional works/factual works – unpublished/published • Amount of the portion used • Impact on Potential Market – rival definitions of “market” – only substitution effects are cognizable Fair Use Doctrine -- as applied in Sega • Purpose and Character of the Use – commercial use: purpose of A’s copying was “study” (noncom) – transformative uses: concede no transformative use – parody: n.a. -

A Tour of Maniac Mansion

Written by: Jok Church, Ron Gilbert, Doug Glen, Brenda Laurel, John Sinclair Layout by: Wendy Bertram, Martin Cameron, Gary Winnick TM and © 1987, 1988 Lucasfilm Ltd. All rights reserved. MANIAC MANSIONTM Table of Contents Problems? Unusual Questions? Get as much or as little help as you want in the..... ...Maniac Mansion Hint Book pages 1 through 26 Maniac Mansion is full of rooms which are all filled with useful things. Find which is where in the..... ...Maniac Mansion Objects List pages 27 through 30 Maniac Mansion has both stories and stories - the kind that have a beginning, middle and end; and the kind that are filled with rooms. In fact, Maniac Mansion has six full stories of rooms. A floorplan can be found in the..... ...Map of Maniac Mansion pages 31 through 32 Perhaps it's best to follow in the footsteps of one who has gone before. Dave has been there and knows his way around. It could save you lots of trouble. Check out the..... ...Tour of Maniac Mansion pages 33 through 47 Maniac MansionTM Hint Book How to use your Maniac Mansion Hint Book secret decoder strip. The red gelatin strip is provided for your protection. Without it, you couldn't help discovering how to solve all the mysteries. Which would take most of the fun out of the game. With the gelatin strip, you only see the clues that you really need. So you can get yourself out of one jam, and still thoroughly enjoy the next one. Just skim through the hint book until you find the question that has you stumped, then place the gelatin strip over the first line of clues underneath.