Atari Games Corp. V. Nintendo of America, Inc. ATARI GAMES CORP

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A History of Video Game Consoles Introduction the First Generation

A History of Video Game Consoles By Terry Amick – Gerald Long – James Schell – Gregory Shehan Introduction Today video games are a multibillion dollar industry. They are in practically all American households. They are a major driving force in electronic innovation and development. Though, you would hardly guess this from their modest beginning. The first video games were played on mainframe computers in the 1950s through the 1960s (Winter, n.d.). Arcade games would be the first glimpse for the general public of video games. Magnavox would produce the first home video game console featuring the popular arcade game Pong for the 1972 Christmas Season, released as Tele-Games Pong (Ellis, n.d.). The First Generation Magnavox Odyssey Rushed into production the original game did not even have a microprocessor. Games were selected by using toggle switches. At first sales were poor because people mistakenly believed you needed a Magnavox TV to play the game (GameSpy, n.d., para. 11). By 1975 annual sales had reached 300,000 units (Gamester81, 2012). Other manufacturers copied Pong and began producing their own game consoles, which promptly got them sued for copyright infringement (Barton, & Loguidice, n.d.). The Second Generation Atari 2600 Atari released the 2600 in 1977. Although not the first, the Atari 2600 popularized the use of a microprocessor and game cartridges in video game consoles. The original device had an 8-bit 1.19MHz 6507 microprocessor (“The Atari”, n.d.), two joy sticks, a paddle controller, and two game cartridges. Combat and Pac Man were included with the console. In 2007 the Atari 2600 was inducted into the National Toy Hall of Fame (“National Toy”, n.d.). -

Trouble in Toyland Table of Contents

Trouble in Toyland Table of Contents 1. Executive Summary..................................................................................2 2. Introduction...............................................................................................5 3. Choking Hazards Regulatory History .............................................................................5 Requirements of the 1994 Child Safety Protection Act ......................6 4. Phthalates in Children’s Toys ...................................................................7 5. Dangerously Loud Toys............................................................................11 6. Other Toy Hazards ...................................................................................12 7. Gaps Remaining in Toy Safety ................................................................14 8. Positive Trends in 2002 ............................................................................17 9. Appendices...............................................................................................18 The 2002 PIRG Potentially Hazardous Toys List Deaths from Toys 1990-2001 Toys Recalled As a Result of PIRG Toy Surveys PIRG’s 2002 Survey of Online Toy Retailers Toy Companies and their Policies Regarding Phthalates PIRG’s Tips for Toy Safety PIRG’s 2002 Trouble in Toyland Report – Page 1 Executive Summary The 2002 Trouble in Toyland report is the seventeenth annual Public Interest Research Group (PIRG) toy safety survey. PIRG uses its survey to educate parents and the general public -

Accolade-Catalog2

Introduction • • Jack Nicklaus Golf & Course • Design: Signature Edition'" • AI Michaels Announces ~ • HardBall III'" • T • Road & Track®Presents Grand Prix Unlimited'" • • Science Fiction Role-Playing: • Star Control II'" • ® SNOOPY's Game Club'" • • Accolade in Motion • • Sports: Mike Ditka Ultimate • Footbalr & Winter Challenge • • Driving: A Test Drive III: The Passion'" 1 L 0 Role Playing: Elvira®Mistress (J • of the Dark'" & Elvira II the ~ • Jaws of Cerberus'" Graphic Adventure: Les Manley in: Lost in LA'" Science Fiction: Hoverforce'" & Star Contror o Ordering Information Macintosh Titles All Time Favorites Product Availability s 1 Accolade In Motion •••••• From the moment hen it comes to entertainment software, you'll find a game IS Accolade in motion creating the finest and most conceived imaginative computer games on the market today. through design, Whether your favorite genre is sports, driving, role-playing, science fiction or graphic adventure, Accolade has a great ... production, game for you. and meticulous From the soaring drives of Jack Nicklaus to the towering home testing, we runs of HardBall 111- from the blazingly fast Formula One work hard to cars of Grand Prix Unlimited to the white-hot space combat of Star Control 11- Accolade pours on the excitement. produce the We pour out our hearts, too, with children's games like our very finest warm and funny SNOOPY's Game Club. games Accolade is proud that so many of the titles in our constantly possible. growing library have won critical acclaim for their realistic simulations, graphic excellence and absorbing gameplay. Yet it is our minds in motion - the creativity and dedication of our Accolade staff - that is our greatest pride. -

Case History

Page 1 of 15 Case History: Yinjie Soon STS 145, Winter 2002 Page 2 of 15 Yinjie Soon STS145: History of Computer Game Design Final Paper 12 February 2002 Case History Star Control II: The Ur-Quan Masters In July 1990, the two partners who formed the software company Toys for Bob released their first game, Star Control, under game publisher Accolade for the personal computer system. These two men – Paul Reiche III and Fred Ford – were big fans of science fiction, and in Reiche’s case, fantasy role playing games (especially Dungeons and Dragons). Unsurprisingly, the game had a strong science fiction theme and heavy doses of traditional role-playing elements, wherein the player controlled one of two sides in an effort to either take over the universe as the marauding conquerors of the Ur-Quan Hierarchy, or save the universe as the brave defenders of the Alliance of Free Stars. Star Control effectively interleaved elements of strategy and action; the player tried to outwit the opposing forces in various turn-based inter-planetary strategic scenarios, and subsequently engaged enemy ships in real-time “space melee” one-on-one spaceship dogfights, similar in style to Spacewar, the earliest of video games (Derrenbacker). Many of the sequel’s most interesting elements, such as the unique characteristics of each race’s ships and behaviors, were established in this game and would carry on to Star Control 2. Figures 1a and 1b show some scenes from Star Control, illustrating how advanced some of the graphics from the game were for the time (figure 1a is also an early manifestation of the creators’ sense of humor – the ship shown in the middle of the picture is the flagship of an all-female race of humanoids; the explanation behind the visual is left to the reader’s imagination.). -

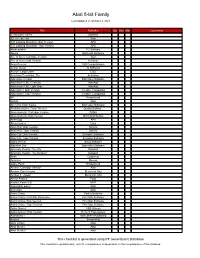

Atari 8-Bit Family

Atari 8-bit Family Last Updated on October 2, 2021 Title Publisher Qty Box Man Comments 221B Baker Street Datasoft 3D Tic-Tac-Toe Atari 747 Landing Simulator: Disk Version APX 747 Landing Simulator: Tape Version APX Abracadabra TG Software Abuse Softsmith Software Ace of Aces: Cartridge Version Atari Ace of Aces: Disk Version Accolade Acey-Deucey L&S Computerware Action Quest JV Software Action!: Large Label OSS Activision Decathlon, The Activision Adventure Creator Spinnaker Software Adventure II XE: Charcoal AtariAge Adventure II XE: Light Gray AtariAge Adventure!: Disk Version Creative Computing Adventure!: Tape Version Creative Computing AE Broderbund Airball Atari Alf in the Color Caves Spinnaker Software Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves Quality Software Alien Ambush: Cartridge Version DANA Alien Ambush: Disk Version Micro Distributors Alien Egg APX Alien Garden Epyx Alien Hell: Disk Version Syncro Alien Hell: Tape Version Syncro Alley Cat: Disk Version Synapse Software Alley Cat: Tape Version Synapse Software Alpha Shield Sirius Software Alphabet Zoo Spinnaker Software Alternate Reality: The City Datasoft Alternate Reality: The Dungeon Datasoft Ankh Datamost Anteater Romox Apple Panic Broderbund Archon: Cartridge Version Atari Archon: Disk Version Electronic Arts Archon II - Adept Electronic Arts Armor Assault Epyx Assault Force 3-D MPP Assembler Editor Atari Asteroids Atari Astro Chase Parker Brothers Astro Chase: First Star Rerelease First Star Software Astro Chase: Disk Version First Star Software Astro Chase: Tape Version First Star Software Astro-Grover CBS Games Astro-Grover: Disk Version Hi-Tech Expressions Astronomy I Main Street Publishing Asylum ScreenPlay Atari LOGO Atari Atari Music I Atari Atari Music II Atari This checklist is generated using RF Generation's Database This checklist is updated daily, and it's completeness is dependent on the completeness of the database. -

Games and Other Uncopyrightable Systems Bruce E

Marquette University Law School Marquette Law Scholarly Commons Faculty Publications Faculty Scholarship 1-1-2011 Games and Other Uncopyrightable Systems Bruce E. Boyden Marquette University Law School, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.marquette.edu/facpub Part of the Law Commons Publication Information Bruce E. Boyden, Games and Other Uncopyrightable Systems, 18 Geo. Mason L. Rev. 439 (2011) Repository Citation Boyden, Bruce E., "Games and Other Uncopyrightable Systems" (2011). Faculty Publications. Paper 82. http://scholarship.law.marquette.edu/facpub/82 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Marquette Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Marquette Law Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 2011] 439 GAMES AND OTHER UNCOPYRIGHTABLE SYSTEMS Bruce E. Boyden* INTRODUCTION Games are deceptively simple objects of human culture.1 They are familiar, commonplace, and often easy to learn: young children play them at an early age. For most people, games are a pastime, a form of recreation that involves relatively little preparation or time commitment.2 They are thus the very opposite of work, and hardly comparable to such serious pursuits as scholarship or art.3 For all their seeming ingenuousness, however, games are also deeply puzzling. Defining games is a notoriously difficult enterprise.4 Scholars from several different disciplines have struggled to determine what the nature, or essence, of games really is. And the elusiveness of games poses problems for intellectual property law as well. -

Download Jumpman Mp3 Free Download Jumpman Junior

download jumpman mp3 free Download Jumpman Junior. Jumpman Junior is a video game published in 1983 on Commodore 64 by Epyx, Inc.. It's an action game, set in a platform theme, and was also released on Atari 8-bit and ColecoVision. Captures and Snapshots. Comments and reviews. Sonic25 2020-12-22 0 point. One of my faves for the C64! Only 12 levels compared to the 30 of the original but well designed and the difficulty ramps up quicker. mymoon 2020-03-29 0 point Commodore 64 version. This is one of the most enjoyable games of its era. Still could not complete it. Should try again. Mr Vampire 2019-02-09 1 point Commodore 64 version. As good as the original Jumpman. Played this almost as much as the first one back in the 80's when dayglow socks were trendy not camp. Enric 2018-08-08 1 point ColecoVision version. I had this on collecovision and is an mazing game for those who wish the improve on everything. Love it. unknXwn 2017-07-25 -1 point Commodore 64 version. I had this on the ol C64 in the 90's when I was a kid. I got caught up on games before I hit the Playstation. Write a comment. Share your gamer memories, help others to run the game or comment anything you'd like. If you have trouble to run Jumpman Junior (Commodore 64), read the abandonware guide first! Download Jumpman Junior. We may have multiple downloads for few games when different versions are available. Also, we try to upload manuals and extra documentations when possible. -

Sega Enterprises LTD. V. Accolade, Inc.: What's So Fair About Reverse Engineering?

Loyola of Los Angeles Entertainment Law Review Volume 14 Number 3 Article 3 3-1-1994 Sega Enterprises LTD. v. Accolade, Inc.: What's so Fair about Reverse Engineering? David C. MacCulloch Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/elr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation David C. MacCulloch, Sega Enterprises LTD. v. Accolade, Inc.: What's so Fair about Reverse Engineering?, 14 Loy. L.A. Ent. L. Rev. 465 (1994). Available at: https://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/elr/vol14/iss3/3 This Notes and Comments is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews at Digital Commons @ Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Loyola of Los Angeles Entertainment Law Review by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NOTES SEGA ENTERPRISES LTD. v. ACCOLADE, INC.: WHAT'S SO FAIR ABOUT REVERSE ENGINEERING? I. INTRODUCTION You are the president of a major corporation that develops and distributes computer video game cartridges and the consoles on which the games can be played. Your company has maintained a majority of the market share by remaining at the forefront of the game cartridges field. Your company's ability to be the first to incorporate all the latest enhance- ments is due to the efforts of one man-your chief designer of game concepts. If he were to leave, your company's position as number one in the industry would be jeopardized. One day, your chief designer demands that if he is not made an executive vice-president and equity shareholder in the company he will resign and take with him a new concept he has been privately developing at home that will take video game technology to the next level. -

Newagearcade.Com 5000 in One Arcade Game List!

Newagearcade.com 5,000 In One arcade game list! 1. AAE|Armor Attack 2. AAE|Asteroids Deluxe 3. AAE|Asteroids 4. AAE|Barrier 5. AAE|Boxing Bugs 6. AAE|Black Widow 7. AAE|Battle Zone 8. AAE|Demon 9. AAE|Eliminator 10. AAE|Gravitar 11. AAE|Lunar Lander 12. AAE|Lunar Battle 13. AAE|Meteorites 14. AAE|Major Havoc 15. AAE|Omega Race 16. AAE|Quantum 17. AAE|Red Baron 18. AAE|Ripoff 19. AAE|Solar Quest 20. AAE|Space Duel 21. AAE|Space Wars 22. AAE|Space Fury 23. AAE|Speed Freak 24. AAE|Star Castle 25. AAE|Star Hawk 26. AAE|Star Trek 27. AAE|Star Wars 28. AAE|Sundance 29. AAE|Tac/Scan 30. AAE|Tailgunner 31. AAE|Tempest 32. AAE|Warrior 33. AAE|Vector Breakout 34. AAE|Vortex 35. AAE|War of the Worlds 36. AAE|Zektor 37. Classic Arcades|'88 Games 38. Classic Arcades|1 on 1 Government (Japan) 39. Classic Arcades|10-Yard Fight (World, set 1) 40. Classic Arcades|1000 Miglia: Great 1000 Miles Rally (94/07/18) 41. Classic Arcades|18 Holes Pro Golf (set 1) 42. Classic Arcades|1941: Counter Attack (World 900227) 43. Classic Arcades|1942 (Revision B) 44. Classic Arcades|1943 Kai: Midway Kaisen (Japan) 45. Classic Arcades|1943: The Battle of Midway (Euro) 46. Classic Arcades|1944: The Loop Master (USA 000620) 47. Classic Arcades|1945k III 48. Classic Arcades|19XX: The War Against Destiny (USA 951207) 49. Classic Arcades|2 On 2 Open Ice Challenge (rev 1.21) 50. Classic Arcades|2020 Super Baseball (set 1) 51. -

Organization of Computer Programs Organization of Computer Programs

Organization of Computer Programs Organization of Computer Programs Hardware Organization of Computer Programs Operating System Hardware Organization of Computer Programs Application Application Program Program Operating System Hardware Interoperability Application Application Program Program Operating System Hardware Interoperability Application Application Program Program Operating System Hardware Interoperability Strategy #1 (e.g., Microsoft, Apple) Borland Microsoft Free access Microsoft Dell Interoperability Strategy #2 (e.g., Sega, Nintendo) Licensee Nintendo License fees Nintendo Nintendo Interoperability Strategy #3 (e.g., MAI Systems Corp.) MAI MAI No licenses MAI MAI Sega (CA9 1992) Licensed Sega Games Games License fees TMSS Sega Genesis III Sega (CA9 1992) Licensed Sega Games Games Accolade Games License fees TMSS Lock-out Sega Genesis III Sega (CA9 1992) Microcode (copied by Accolade) Licensed Sega Games Games Accolade Games License fees TMSS Lock-out Sega Genesis III Sega (CA9 1992) Licensed Sega Games Games Accolade Games License fees TMSS TMSS initialization Lock-out code Sega Genesis III Sega (CA9 1992) Licensed Sega Games Games Accolade Games License fees TMSS Sega Genesis III Reverse Engineering for Interoperability • Courts finding this to be fair use: – CAFC (Atari 1992 [dictum]; Bowers 2003 [dictum]) – CA5 (DSC Communications 1996) – CA 9 (Sega 1992; Sony 2000) – CA11 (Bateman 1996) • EC Directive 91/250, Art. 6, takes same position Fair Use Doctrine • Purpose and Character of the Use – commercial use – transformative uses – parody – propriety of defendant’s conduct • Nature of the Copyrighted Work – fictional works/factual works – unpublished/published • Amount of the portion used • Impact on Potential Market – rival definitions of “market” – only substitution effects are cognizable Fair Use Doctrine -- as applied in Sega • Purpose and Character of the Use – commercial use: purpose of A’s copying was “study” (noncom) – transformative uses: concede no transformative use – parody: n.a. -

Press Release Retro Gaming Platform Antstream Announces First

Press Release Retro Gaming Platform Antstream Announces First Wave Partnerships with Legendary Game Brands Ahead of Global Launch SNK, Data East, Epyx, Gremlin Interactive And Technōs Among The Iconic Game Brands Players Will Find On The Service At Launch Q1 2019 London, United Kingdom - 13 December, 2018 - Antstream, the upcoming gaming platform dedicated to retro games, is proud to announce it has secured a partnership with five legendary gaming brands and will be able to offer a variety of their most famous titles at launch. Antstream will then feature multiple games from: ● SNK (Ikari Warriors) ● Data East (Joe & Mac) ● Epyx (California Games) ● Gremlin Interactive (Zool) ● Technōs (Double Dragon) Antstream will offer its subscribers an easy, legal, and fun way to play thousands of classic games that have previously been beyond the reach of most gamers. Antstream is set to launch on PC, Mac, Xbox One, Tablets and Smartphones in Q1 2019. “Giving instant access to great games is at the heart of what we are building, tracking down and securing the rights of those titles that are the foundation of videogaming is no easy task, and the partners we are able to announce today are just the tip of the iceberg of what we have planned.” said Steve Cottam CEO at Antstream. “The video games industry had been suffering from the absence of a way for many arcade games to be played years after their original platform disappeared,” said Koichi Toyama, Company President & CEO at SNK. “We are working with Antstream to right this wrong, and allow everyone to play and challenge their friends at some of our most iconic retro titles.” In the new year, Antstream will reveal more about its plan to bring back retro games to the world, players can register today on the website to be the first informed: www.antstream.com. -

Pokemon Fans Can Now Choose Yahoo! Auctions to Bid on Hasbro's

Pokemon Fans Can Now Choose Yahoo! Auctions To Bid On Hasbro's "I Choose You Pikachu™" Toys Charity Auction of "Must Have" Toy for Holiday Season to Benefit Hasbro Children's Hospital Pokemon Fans Can Now Choose Yahoo! Auctions To Bid On Hasbro's "I Choose You Pikachu™" Toys Charity Auction of "Must Have" Toy for Holiday Season to Benefit Hasbro Children's Hospital CINCINNATI, OH -- December 2, 1999 -- Consumers can help make a difference in the lives of children this holiday season by heading to Yahoo!® Auctions (http://auctions.yahoo.com). Hasbro, Inc. (NYSE: HAS) today announced that it has teamed with Yahoo! Inc. (NASDAQ: YHOO) to host a series of online auctions of Hasbro's "I Choose You Pikachu," already a hot toy since making its retail debut in November. "I Choose You Pikachu" is the first in a series of electronic plush Pokémon toys to be released by Hasbro, Nintendo's worldwide master toy and board game licensee for Pokémon. "Pokémon, The First Movie " opened to record box office attendance in November. "I Choose You Pikachu" is no ordinary plush toy; it is an electronic plush version of the most popular Pokémon character of all, #25 Pikachu. The adorable eight-inch huggable Pikachu is the ultimate combination of today's hot electronic plush toy and the even hotter Pokémon phenomenon. All proceeds from the Yahoo! charity auction will benefit Hasbro Children's Hospital in Providence, Rhode Island. The more that kids interact with their "I Choose You Pikachu," the more talkative it gets. Squeeze its hand and Pikachu's mouth wiggles while saying its name (at first, "Pi," then "Pi-ka," then "Pikachu!").