Ecologizing Industrialization in Chinese Small Towns

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

馬 鞍 山 鋼 鐵 股 份 有 限 公 司 Maanshan Iron & Steel Company

Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing Limited and The Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited take no responsibility for the contents of this announcement, make no representation as to its accuracy or completeness, and expressly disclaim any liability whatsoever for any loss howsoever arising from or in reliance upon the whole or any part of the contents of this announcement. 馬鞍山鋼鐵股份有限公司 Maanshan Iron & Steel Company Limited (A joint stock limited company incorporated in the People’s Republic of China) (Stock Code: 00323) ANNOUNCEMENT IN RELATION TO THE CONFIRMATION OF GAINS ON THE DISPOSAL OF ASSETS BY CONTROLLING SUBSIDIARY Reference is made to the announcement of Maanshan Iron & Steel Company Limited (the “Company”) dated 6 March 2014 in relation to the discloseable transaction - disposal of land. As China has attached increasing importance to the issue of pollution and protection of environment, Ma Steel (Hefei) Iron & Steel Co., Ltd. (“Ma Steel (Hefei)”), a 71%-owned controlling subsidiary of the Company, entered into the “Resumption Contract for the Land Use Right of State-owned Land for Construction in Hefei” (the “Contract”) with the Land Reserve Centre of Hefei on 28 February 2014 to phase out inefficient and obsoleted smelting facilities and to initiate the transition to a new business model, stipulating that the Land Reserve Center of Hefei would resume a land parcel granted to Ma Steel (Hefei) in Yaohai District of Hefei with an area of 3,377.9 mu and part of the buildings and structures erected thereon; the Land Reserve Center of Hefei would pay no less than RMB1.2 billion to Ma Steel (Hefei) as compensation in four installments and the specific amount shall be subject to the pro forma audit of the appraised price. -

Ethical Sourcing at the Warehouse 2018 Report 2019 Update 2 Contents

ETHICAL SOURCING AT THE WAREHOUSE 2018 REPORT 2019 UPDATE 2 CONTENTS ETHICAL SOURCING AT THE WAREHOUSE CONTENTS 2018 REPORT Ethical Sourcing 4 // Introduction at The Warehouse 5 // The Warehouse and its supply chains 2018 & 2019 Report 7 // Ethical sourcing programme structure The structure and content of this report was informed by: 13 // Policy Themes and commentary The Warehouse Group Ethical 5.1 Management Systems Sourcing Policy (2017) 5.2 Child Labour The Modern Slavery Act 5.3 Voluntary Labour (UK) 2015 and its guidance 5.4 Health & Safety on Transparency in Supply 5.5 Wages and Benefts Chains. 5.6 Working Hours Baptist World Aid Australia’s 5.7 Freedom of Association and Collective Bargaining ongoing series of “Behind 5.8 Environment the Barcode“ reports on the 5.9 Subcontracting Fashion industry. 5.10 Business Integrity Data within this report is derived from labour 22 // New Initiatives audits undertaken for Apparel Supplier Survey & Tier 2 Discovery The Warehouse in calendar Customer Survey – New Zealanders views on Ethical Sourcing years, 2017 & 2018 and from our internal purchase ELearning – online resources for factory managers order management Worker Voice - Integrated Audits systems. Responsible Workplace Programme - Malaysia Where data or commentary 31 // Trending now is derived from external Transparency sources these are referenced in the footnotes Living wages on each page. Bangladesh Human Trafcking and Modern Slavery The report was compiled and authored by our Ethical 37 // Programme Update January 2019 Sourcing Manager and reviewed and approved by 40 // Appendices our Executive. Factory Lists List of The Warehouse’s Private Label (“House”) Brands Country Working Hour and Wages table 3 INTRODUCTION INTRODUCTION The Warehouse Ltd is the largest subsidiary of The Warehouse Group1 – New Zealand’s largest publicly listed non-food retailer. -

Huishang Bank Corporation Limited* 徽 商 銀 行 股 份 有 限

Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing Limited and The Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited take no responsibility for the contents of this announcement, make no representation as to its accuracy or completeness and expressly disclaim any liability whatsoever for any loss howsoever arising from or in reliance upon the whole or any part of the contents of this announcement. Huishang Bank Corporation Limited* 徽商銀行股份有限公司* (A joint stock company incorporated in the People’s Republic of China with limited liability) (Stock Code: 3698 and 4608 (Preference shares)) 2017 INTERIM RESULTS ANNOUNCEMENT The board of directors (the“ Board”) of Huishang Bank Corporation Limited (the “Bank”) is pleased to announce the unaudited interim results of the Bank and its subsidiaries for the six months ended June 30, 2017. This announcement, containing the full text of the 2017 Interim Report of the Bank, complies with the relevant content requirements of the Rules Governing the Listing of Securities on The Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited in relation to preliminary announcements of interim results. The printed version of the Bank’s 2017 Interim Report will be delivered to the holders of H Shares of the Bank and available for viewing on the websites of Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing Limited at www.hkexnews.hk and of the Bank at www.hsbank.com.cn in September 2017. By order of the Board Huishang Bank Corporation Limited* Li Hongming Chairman Hefei, Anhui Province, China August 25, 2017 As at the date of this announcement, the board of directors of the Bank comprises Li Hongming, Wu Xuemin and Ci Yaping as executive directors; Zhang Feifei, Zhu Jiusheng, Qian Li, Lu Hui, Zhao Zongren, Qiao Chuanfu and Gao Yang as non-executive directors; Au Ngai Daniel, Dai Genyou, Wang Shihao, Zhang Shenghuai and Zhu Hongjun as independent non-executive directors. -

Analysis of Character Convergence of Jiangnan Ancient Towns Lei Yunyao , Zhang Qiongfang

International Forum on Management, Education and Information Technology Application (IFMEITA 2016) Analysis of Character Convergence of Jiangnan Ancient Towns Lei Yunyao1, a, Zhang Qiongfang 1,b 1 Wuchang Shouyi University, Wuhan 430064 China [email protected], b [email protected] Key Words:Jiangnan Ancient Towns; Character convergence; Analysis Abstract:This article illustrates the representation of character convergence of Jiangnan Ancient Towns. It analyzes the formation mechanism of character convergence to build the whole image of these ancient towns with Zhouzhuang as a prototype. Based on Tourism Geography Theory and Regional Linkage Theory, it puts forward the fact that the character convergence can be beneficial to building a whole tourism image and to enhancing people’s awareness of ancient heritage. But some problems caused by the convergence will also be presented, such as the identical tourism development model, the backward infrastructure and the destruction of original ecology. Introduction With Taihu Lake as the center, the region of Jiangnan, the south of the lower reaches of the Yangtze River, is scattered all over by many historic ancient towns. These towns have a long history and deep cultural deposit. They are densely occupied and economically developed. They form a national transport network combined with inland waterway. These towns have witnessed a long-term economic prosperity in the south of the lower reaches of the Yangtze River and are now generally called “Jiangnan Ancient Towns”. Since 1980s, under the wave of reform, opening up and modernization construction, experience-based tourism and leisure tourism of these towns have achieved great development. Under the influence of “China's First Water Town” Zhouzhuang, some other similar towns like Tongli, Luzhi, Xitang, Nanxun, Wuzhen all choose to follow suit. -

Proquest Dissertations

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy sutxnitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indisünct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6” x 9” black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. Bell & Howell Information and Leaming 300 North Zeeb Road. Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA 800-521-0600 UMÏ METAPHORS OF EXCHANGE AND THE SHANGHAI STOCK MARKET DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School o f The Ohio State University By Susan Diane Menke, M A ***** The Ohio State University 2000 Dissertation committee: Approved by: Dr. -

Risky Expertise in Chinese Financialisation Haigui Returnee Migrants in the Shanghai Financial Market

Risky Expertise in Chinese Financialisation Haigui Returnee Migrants in the Shanghai Financial Market. A thesis submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the award for the degree Doctorate of Philosophy From Western Sydney University Giulia Dal Maso Institute for Culture and Society Western Sydney University 2016 Statement of Authentication The work presented in this thesis is, to the best of my knowledge and belief, original except as acknowledged in the text. I hereby declare that I have not submitted this material, either in full or in part, for a degree at this or any other institution. Sections of chapter 5 have been previsouly published in Dal Maso, Giulia. “The Financialisation Rush: Responding to Precarious Labor and Social Security by Investing in the Chinese Stock Market.” South Atlantic Quarterly 114, no. 1: 47-64. ............................................................................... (Signature) Acknowledgements I would like to thank my supervisors Professor Brett Neilson and Professor Ned Rossiter for their extraordinary intellectual support, encouragement and incredible patience. They have been invaluable interlocutors and the best supervisors I could hope for. My gratitude also goes to Professor Sandro Mezzadra for his intellectual generosity, guidance and for having encouraged me many times. It is thanks to him that my Chinese adventure started. Particular thanks go to Giorgio Casacchia. His support has been essential both for the time of my research fieldwork and for sustenance when writing. He has not -

Table of Codes for Each Court of Each Level

Table of Codes for Each Court of Each Level Corresponding Type Chinese Court Region Court Name Administrative Name Code Code Area Supreme People’s Court 最高人民法院 最高法 Higher People's Court of 北京市高级人民 Beijing 京 110000 1 Beijing Municipality 法院 Municipality No. 1 Intermediate People's 北京市第一中级 京 01 2 Court of Beijing Municipality 人民法院 Shijingshan Shijingshan District People’s 北京市石景山区 京 0107 110107 District of Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 人民法院 Municipality Haidian District of Haidian District People’s 北京市海淀区人 京 0108 110108 Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 民法院 Municipality Mentougou Mentougou District People’s 北京市门头沟区 京 0109 110109 District of Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 人民法院 Municipality Changping Changping District People’s 北京市昌平区人 京 0114 110114 District of Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 民法院 Municipality Yanqing County People’s 延庆县人民法院 京 0229 110229 Yanqing County 1 Court No. 2 Intermediate People's 北京市第二中级 京 02 2 Court of Beijing Municipality 人民法院 Dongcheng Dongcheng District People’s 北京市东城区人 京 0101 110101 District of Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 民法院 Municipality Xicheng District Xicheng District People’s 北京市西城区人 京 0102 110102 of Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 民法院 Municipality Fengtai District of Fengtai District People’s 北京市丰台区人 京 0106 110106 Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 民法院 Municipality 1 Fangshan District Fangshan District People’s 北京市房山区人 京 0111 110111 of Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 民法院 Municipality Daxing District of Daxing District People’s 北京市大兴区人 京 0115 -

Spatial Distribution Pattern of Minshuku in the Urban Agglomeration of Yangtze River Delta

The Frontiers of Society, Science and Technology ISSN 2616-7433 Vol. 3, Issue 1: 23-35, DOI: 10.25236/FSST.2021.030106 Spatial Distribution Pattern of Minshuku in the Urban Agglomeration of Yangtze River Delta Yuxin Chen, Yuegang Chen Shanghai University, Shanghai 200444, China Abstract: The city cluster in Yangtze River Delta is the core area of China's modernization and economic development. The industry of Bed and Breakfast (B&B) in this area is relatively developed, and the distribution and spatial pattern of Minshuku will also get much attention. Earlier literature tried more to explore the influence of individual characteristics of Minshuku (such as the design style of Minshuku, etc.) on Minshuku. However, the development of Minshuku has a cluster effect, and the distribution of domestic B&Bs is very unbalanced. Analyzing the differences in the distribution of Minshuku and their causes can help the development of the backward areas and maintain the advantages of the developed areas in the industry of Minshuku. This article finds that the distribution of Minshuku is clustered in certain areas by presenting the overall spatial distribution of Minshuku and cultural attractions in Yangtze River Delta and the respective distribution of 27 cities. For example, Minshuku in the central and eastern parts of Yangtze River Delta are more concentrated, so are the scenic spots in these areas. There are also several concentrated Minshuku areas in other parts of Yangtze River Delta, but the number is significantly less than that of the central and eastern regions. Keywords: Minshuku, Yangtze River Delta, Spatial distribution, Concentrated distribution 1. -

Facile Fabrication of Ultra-Light and Highly Resilient PU/RGO Foams for Microwave

Electronic Supplementary Material (ESI) for RSC Advances. This journal is © The Royal Society of Chemistry 2017 Supporting Information Facile fabrication of ultra-light and highly resilient PU/RGO foams for microwave absorption Chunmei Zhanga,+, Hua Lia,b,+,*, Zhangzhi Zhuoc, Roberto Dugnanid, Chongyang Suna , Yujie Chena,*, Hezhou Liua,b aState Key Laboratory of Metal Matrix Composites, School of Materials Science and Engineering, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, Dongchuan Road No. 800, Shanghai 200240, China. bCollaborative Innovation Center for Advanced Ship and deep-Sea Exploration, Shanghai Jiao Tong University. cWuHu State-owned Factory of Machining, Jiujiang District Wanli Village No. 99, WuHu 241000, China. dUniversity of Michigan-Shanghai Jiao Tong University Joint Institute. *Corresponding author: Hua Li (email: [email protected]) or Yujie Chen (email: [email protected]) +These authors contributed equally to this work. Figure S1 SEM images of PU/RGO foams with different loadings of RGO: (a) and (b) sample S- 3, (c) and (d) sample S-6, (e) and (f) sample S-9, (g) and (h) sample S-12, and (i) and (j) sample S-15 Figure S2 The photos of the PU foam and the prepared PU/RGO foams with different RGO loadings Figure S3 Schematic illustration of the dissipation routes of microwaves irradiated in the PU/RGO foams Figure S4 The variation curves of (a) SETotal, (b) SEA, and (c) SER of samples with different RGO loadings in the frequency range of 2 - 18 GHz The samples used for electromagnetic shielding performance measurements were made into toroidal-shaped specimens with an outer diameter of 7.0 mm and an inner diameter of 3.04 mm. -

CHINA VANKE CO., LTD.* 萬科企業股份有限公司 (A Joint Stock Company Incorporated in the People’S Republic of China with Limited Liability) (Stock Code: 2202)

Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing Limited and The Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited take no responsibility for the contents of this announcement, make no representation as to its accuracy or completeness and expressly disclaim any liability whatsoever for any loss howsoever arising from or in reliance upon the whole or any part of the contents of this announcement. CHINA VANKE CO., LTD.* 萬科企業股份有限公司 (A joint stock company incorporated in the People’s Republic of China with limited liability) (Stock Code: 2202) 2019 ANNUAL RESULTS ANNOUNCEMENT The board of directors (the “Board”) of China Vanke Co., Ltd.* (the “Company”) is pleased to announce the audited results of the Company and its subsidiaries for the year ended 31 December 2019. This announcement, containing the full text of the 2019 Annual Report of the Company, complies with the relevant requirements of the Rules Governing the Listing of Securities on The Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited in relation to information to accompany preliminary announcement of annual results. Printed version of the Company’s 2019 Annual Report will be delivered to the H-Share Holders of the Company and available for viewing on the websites of The Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited (www.hkexnews.hk) and of the Company (www.vanke.com) in April 2020. Both the Chinese and English versions of this results announcement are available on the websites of the Company (www.vanke.com) and The Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited (www.hkexnews.hk). In the event of any discrepancies in interpretations between the English version and Chinese version, the Chinese version shall prevail, except for the financial report prepared in accordance with International Financial Reporting Standards, of which the English version shall prevail. -

De La Música Tradicional De China. Selección

Discografía de la música tradicional de China. Selección Biblioteca Fundación Juan March Esta selección discográfica ha sido preparada con motivo de la exposición El principio Asia. China, Japón e India y el arte contemporáneo en España (1957-2017) y del ciclo de cinco conciertos Oriente y la música occidental. Durante la preparación de esta discografía no han sido incluidos numerosos registros publicados en China de muy difícil localización en Occidente. Tampoco se mencionan grabaciones sonoras anteriores al vinilo. Las músicas que aparecen en estos discos son un breve apunte de la riqueza musical tradicional que aún se practica en este país. Muchos de estos soportes sonoros han sido y son, además, fuente de estudio para compositores e intérpretes occidentales. La influencia de estas músicas sobre las técnicas compositivas, el timbre vocal e instrumental o sobre la concepción del tiempo musical es esencial para comprender una gran parte de la historia musical del siglo XX. Selección discográfica de José Luis Maire Biblioteca Fundación Juan March Abril de 2018 Música y canto budista La liturgia budista y taoísta en China tiene una historia de casi 2000 años y todavía se practica ampliamente en la actualidad. Desde su llegada a China hasta las llamadas tres dinastías del Norte y del Sur (420-589 d. C.), el budismo sufrió un proceso de consolidación hasta su profunda adaptación. Como numerosos documentos históricos demuestran (textos, pinturas y esculturas), el budismo introdujo en China nuevos géneros y prácticas rituales de una manera progresiva. Uno de los géneros más representativos y específicos de la liturgia vocal china es el denominado canto fanbei, caracterizado por la construcción de melodías melismáticas surgidas como consecuencia de un proceso de transculturación con las formas nativas de China. -

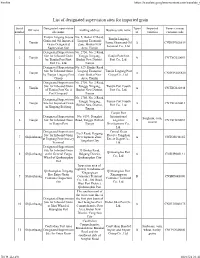

List of Designated Supervision Sites for Imported Grain

Firefox https://translate.googleusercontent.com/translate_f List of designated supervision sites for imported grain Serial Designated supervision Types Imported Venue (venue) Off zone mailing address Business unit name number site name of varieties customs code Tianjin Lingang Jiayue No. 5, Bohai 37 Road, Tianjin Lingang Grain and Oil Imported Lingang Economic 1 Tianjin Jiayue Grain and Oil A CNDGN02S619 Grain Designated Zone, Binhai New Terminal Co., Ltd. Supervision Site Area, Tianjin Designated Supervision No. 2750, No. 2 Road, Site for Inbound Grain Tanggu Xingang, Tianjin Port First 2 Tianjin A CNTXG020051 by Tianjin Port First Binhai New District, Port Co., Ltd. Port Co., Ltd. Tianjin Designated Supervision No. 529, Hunhe Road, Site for Inbound Grain Lingang Economic Tianjin Lingang Port 3 Tianjin A CNDGN02S620 by Tianjin Lingang Port Zone, Binhai New Group Co., Ltd. Group Area, Tianjin Designated Supervision No. 2750, No. 2 Road, Site for Inbound Grain Tanggu Xingang, Tianjin Port Fourth 4 Tianjin A CNTXG020448 of Tianjin Port No. 4 Binhai New District, Port Co., Ltd. Port Company Tianjin No. 2750, No. 2 Road, Designated Supervision Tanggu Xingang, Tianjin Port Fourth 5 Tianjin Site for Imported Grain A CNTXG020413 Binhai New District, Port Co., Ltd. in Xingang Beijiang Tianjin Tianjin Port Designated Supervision No. 6199, Donghai International Sorghum, corn, 6 Tianjin Site for Inbound Grain Road, Tanggu District, Logistics B CNTXG020051 sesame in Tianjin Port Tianjin Development Co., Ltd. Designated Supervision Central Grain No.9 Road, Haigang Site for Inbound Grain Reserve Tangshan 7 Shijiazhuang Development Zone, A CNTGS040165 at Jingtang Port Grocery Direct Depot Co., Tangshan City Terminal Ltd.