Yishu Awards for Critical Writing and Curating on Contemporary Chinese Art

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Introducing the 10 Shortlisted Ghetto Film School Fellows for the Inaugural Deutsche Bank Frieze Los Angeles Film Award 2020

Frieze Los Angeles Press Release December 19, 2019 Introducing the 10 Shortlisted Ghetto Film School Fellows for the Inaugural Deutsche Bank Frieze Los Angeles Film Award 2020 Today Frieze and Deutsche Bank announce the ten shortlisted fellows that will headline the inaugural Deutsche Bank Frieze Los Angeles Film Award. Presented in partnership with award-winning, non-profit film academy Ghetto Film School (GFS), the initiative offers a platform and development program for ten emerging, Los Angeles-based filmmakers aged 20-34 years old. Frieze Los Angeles takes place February 14 – 16, 2020 at Paramount Pictures Studios in Hollywood. Launched in 2019, Frieze Los Angeles brings together more than 70 galleries from around the world and is supported by global lead partner Deutsche Bank for the second consecutive year. The ten shortlisted fellows are as follows: Danielle Boyd, Mya Dodson, Michelle Jihyon Kim, Nabeer Khan, Silvia Lara, Alima Lee, Timothy Offor, Toryn Seabrooks, Noah Sellman and Nicole L. Thompson. The recipient of the award, selected by a jury of leading art and entertainment figures including Doug Aitken, Shari Frilot, Jeremy Kagan, Sam Taylor Johnson and Hamza Walker will be announced at a ceremony on February 13 at Paramount Pictures Theatre and receive a $10,000 prize. Selected from an open call throughout Los Angeles, the ten shortlisted fellows completed an intensive three-month program at GFS each producing a short film in response to Los Angeles’ vibrant art, culture and social landscape. The resulting 10 short films will be screened at the Paramount Pictures Theatre throughout the fair, February 14-16, 2020. -

CHROME COULD BE BACK for >18 PEGASUS, and WHY NOT?

TUESDAY, JANUARY 31, 2017 CLYDE RICE PASSES AWAY CHROME COULD BE BACK by Jessica Martini FOR >18 PEGASUS, Clyde Rice, the patriarch of a far-ranging family of trainers, jockeys and consignors, passed away Monday at his home in AND WHY NOT? Anthony, Florida. He was 79. A native of Antigo, Wisconsin, Rice was a high school teacher before deciding to pursue a career in the horse industry. Several times leading trainer at Penn National in the 1970s and 80s, he became a pioneer in the yearling-to-juvenile pinhooking market, raising horses at his Indian Prairie Ranch in Anthony. Rice grew up alongside future Hall of Fame trainer D. Wayne Lukas and the two men shared a passion for horses. AHe was a dear friend and I can=t tell you what a great horseman he was,@ Lukas recalled Monday. AWe grew up about a half-mile apart and spent our whole boyhoods with these horses and traveling miles and miles to sales and shows. He was special and he had a great knack, a really good eye for a horse.@ Cont. p4 IN TDN EUROPE TODAY California Chrome in Gulfstream paddock | A Coglianese STEWARD’S CUP GOES TO PARAGON by Bill Finley Helene Paragon (Fr) (Polan {Fr}), formerly trained in Spain, Ask someone in horse racing why things are done a certain landed the G1 Stewards’ Cup at Sha Tin on Monday. Click or way and the answer is usually Abecause that=s the way it=s tap here to go straight to TDN Europe. always been done.@ It=s a terrible answer and speaks to an industry so stuck in the past that it's afraid to try anything new and innovative. -

Frieze Los Angeles: Announcing Highlights for the Inaugural Edition

Frieze Los Angeles Press Release January 23, 2019 Frieze Los Angeles: Announcing Highlights for the Inaugural Edition Hosted at Paramount Pictures Studios, Including Special Gallery Presentations and Curated Artist Projects, Talks and Film More than 70 invited galleries will take part in the first Frieze Los Angeles – including a special selection of emerging spaces from the city – presenting a global cross-section of today’s most significant and exciting artists and creating an exceptional opportunity for collecting and discovery The curated program will celebrate the unique creative spirit of Los Angeles. Artist projects, talks, films, restaurants and experiments in patronage and activism, will transform the movie set backlot of Paramount Pictures Studios into a symbolic cityscape where art is at the center of civic life Frieze today announces the programs and highlights for the launch edition of Frieze Los Angeles. The new annual contemporary art fair will feature more than 70 L.A.-based and international galleries, alongside a site-specific program of talks, music and commissioned artist projects. Organized in collaboration with leading curators and working closely with venue partner Paramount Pictures Studios, Frieze Los Angeles joins Frieze New York, Frieze London and Frieze Masters at the forefront of the international art fair calendar, celebrating Los Angeles’ position as a global arts center and destination. Global lead partner Deutsche Bank will support the inaugural edition of Frieze Los Angeles, continuing a shared commitment to discovery and artistic excellence. Taking place in a bespoke structure designed by Kulapat Yantrasast, Frieze Los Angeles is led by Victoria Siddall (Director, Frieze Fairs) and Bettina Korek (Executive Director, Frieze Los Angeles). -

Frieze Los Angeles Press Release September 12, 2018

Frieze Los Angeles Press Release September 12, 2018 Frieze Los Angeles: Announcing Galleries and Curators for the Inaugural Edition Around 70 galleries will take part in the first Frieze Los Angeles, including a special selection of emerging spaces from Los Angeles Curator Hamza Walker to program Frieze Talks and Frieze Music Frieze today announces the 68 participating galleries in the inaugural edition of Frieze Los Angeles. The new annual contemporary art fair will feature a site-specific program of talks, music and commissioned artist projects organized in collaboration with leading curators. Opening at Paramount Pictures Studios in Hollywood from February 14 through February 17, 2019, Frieze Los Angeles will join Frieze New York, Frieze London and Frieze Masters at the forefront of the international art fair calendar, celebrating Los Angeles’ position as a global arts center and destination. Taking place in a bespoke structure designed by Kulapat Yantrasast, Frieze Los Angeles is led by Bettina Korek (Executive Director, Frieze Los Angeles) working with Victoria Siddall (Director, Frieze Fairs). Joining them is the newly announced curator of Frieze Talks and Music, Hamza Walker (Executive Director, LAXART), and Ali Subotnick, who will commission Frieze Projects and Frieze Film. Also announced today Frieze Los Angeles will be supported by Deutsche Bank, global lead partner for Frieze London, Frieze Masters and Frieze New York. Victoria Siddall said, “The extremely positive reaction to Frieze Los Angeles from galleries is testament to the importance of this city which is so rich in great artists, museums, galleries, and art schools. I am thrilled with the response we have had and the strength of the exhibitor list, which includes exceptional contemporary art galleries from around the world as well as leading established and emerging spaces from LA. -

M. Paul Friedberg Reflections

The Cultural Landscape Foundation Pioneers of American Landscape Design ___________________________________ M. PAUL FRIEDBERG ORAL HISTORY REFLECTIONS ___________________________________ Howard Abel Jim Balsley Charlotte Frieze Bernard Jacobs Sonja Johansson Signe Nielson Nicholas Quennell Lee Weintraub Mingkuo Yu © 2009 The Cultural Landscape Foundation, all rights reserved. May not be used or reproduced without permission. Reflections on M. Paul Friedberg from Howard Abel April 2009 I worked with Paul from 1961-1964 with a 6 month Army Reserve tour in the middle. When I began there were four of us in the office. The office was in an apartment on 86th Street and Madison Avenue with Paul working out of the kitchen and Walter Diakow, his partner, and Phil Loman and myself in the converted living room. Paul used the back bedroom as his living quarters. I had been out of school for about six months and had worked for a traditional landscape architectural firm before joining Paul's office. The pace and excitement were electrifying. We worked on lots of small projects, mainly housing with Paul wanting to try ten new ideas for each project. He usually got at least one but at the end of the tenth project he'd have his ten and just kept on going. His vision on how urban space should be used and defined was quite different from the then thinking current attitude. His work seemed to be intuitive and emotional usually thinking how people would fit into the landscape. Proportion, scale and use of material took on a completely different meaning. I always marveled that he was willing to try to do anything. -

![World History--Part 1. Teacher's Guide [And Student Guide]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1845/world-history-part-1-teachers-guide-and-student-guide-2081845.webp)

World History--Part 1. Teacher's Guide [And Student Guide]

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 462 784 EC 308 847 AUTHOR Schaap, Eileen, Ed.; Fresen, Sue, Ed. TITLE World History--Part 1. Teacher's Guide [and Student Guide]. Parallel Alternative Strategies for Students (PASS). INSTITUTION Leon County Schools, Tallahassee, FL. Exceptibnal Student Education. SPONS AGENCY Florida State Dept. of Education, Tallahassee. Bureau of Instructional Support and Community Services. PUB DATE 2000-00-00 NOTE 841p.; Course No. 2109310. Part of the Curriculum Improvement Project funded under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), Part B. AVAILABLE FROM Florida State Dept. of Education, Div. of Public Schools and Community Education, Bureau of Instructional Support and Community Services, Turlington Bldg., Room 628, 325 West Gaines St., Tallahassee, FL 32399-0400. Tel: 850-488-1879; Fax: 850-487-2679; e-mail: cicbisca.mail.doe.state.fl.us; Web site: http://www.leon.k12.fl.us/public/pass. PUB TYPE Guides - Classroom - Learner (051) Guides Classroom Teacher (052) EDRS PRICE MF05/PC34 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Academic Accommodations (Disabilities); *Academic Standards; Curriculum; *Disabilities; Educational Strategies; Enrichment Activities; European History; Greek Civilization; Inclusive Schools; Instructional Materials; Latin American History; Non Western Civilization; Secondary Education; Social Studies; Teaching Guides; *Teaching Methods; Textbooks; Units of Study; World Affairs; *World History IDENTIFIERS *Florida ABSTRACT This teacher's guide and student guide unit contains supplemental readings, activities, -

Unbridled Achievement SMU 2011-12 ANNUAL REPORT TABLE of CONTENTS

UNBRIDLED ACHIEVEMENT SMU 2011-12 ANNUAL REPORT TABLE OF CONTENTS 4 | SMU BOARD OF TRUSTEES 2011–12 5 | LETTER FROM THE CHAIR OF THE BOARD OF TRUSTEES 6 | SMU ADMINISTRATION 2011–12 7 | LETTER FROM THE PRESIDENT 8 | THE SECOND CENTURY CELEBRATION 14 | PROGRESS REPORT Student Quality Faculty and Academic Excellence Campus Experience 38 | FINANCIAL REPORT Consolidated Financial Statements Expenditures Toward Strategic Goals Endowment Report Campaign Update Yearly Giving 48 | HONOR ROLLS Second Century Campaign Donors New Endowment Donors New Dallas Hall Society Members President’s Associates Corporations, Foundations and Organizations Hilltop Society 2 | SMU.EDU/ANNUALREPORT In 2011-12 SMU celebrated the second year of the University’s centennial commemoration period marking the 100th anniversaries of SMU’s founding and opening. The University’s progress was marked by major strides forward in the key areas of student quality, faculty and academic excellence and the campus experience. The Second Century Campaign, the largest fundraising initiative in SMU history, continued to play an essential role in drawing the resources that are enabling SMU to continue its remarkable rise as a top educational institution. By the end of the fiscal year, SMU had received commitments for more than 84 percent of the campaign’s financial goals. Thanks to the inspiring support of alumni, parents and friends of the University, SMU is continuing to build a strong foundation for an extraordinary second century on the Hilltop. SMU BOARD OF TRUSTEES 2011-12 LETTER FROM THE CHAIR OF THE BOARD OF TRUSTEES Caren H. Prothro, Chair Gerald J. Ford ’66, ’69 Helmut Sohmen ’66 Civic and Philanthropic Leader Diamond A Ford Corporation BW Corporation Limited Michael M. -

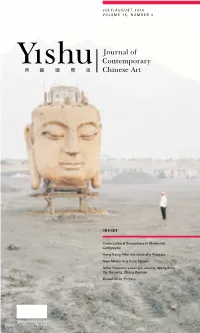

July/August 2016 Volume 15, Number 4 Inside

J U L Y / A U G U S T 2 0 1 6 VOLUME 15, NUMBER 4 INSIDE Cross-Cultural Encounters in Modernist Calligraphy Hong Kong After the Umbrella Protests New Media Arts from Taiwan Artist Features: susan pui san lok, Wang Bing, Xie Nanxing, Zhang Kechun Buried Alive: Preface US$12.00 NT$350.00 PRINTED IN TAIWAN 6 VOLUME 15, NUMBER 4, JULY/AUGUST 2016 CONTENTS 29 2 Editor’s Note 4 Contributors 6 Lines in Translation: Cross-Cultural Encounters in Modernist Calligraphy, Early 1980s–Early 1990s Shao-Lan Hertel 53 29 Spots, Dust, Renderings, Picabia, Case Notes, Flavour, Light, Sound, and More: Xie Nanxing’s Creations Carol Yinghua Lu 45 Zhang Kechun: Photographing "China’s Sorrow" Adam Monohon 53 Hong Kong After the Umbrella Protests John Batten 65 65 RoCH Redux Alice Ming Wai Jim 71 Wuxia Makes Me Nervous Henry Tsang 76 New and Greater Prospects Beyond the Frame: New Media Arts from Taiwan Claudia Bohn-Spector 81 In and Out of the Dark with Extreme Duration: Documenting China One Person at a Time in 76 the Films of Wang Bing Brian Karl 91 Buried Alive: Preface Lu Huanzhi 111 Chinese Name Index Cover: Zhang Kechun, Buddha in a Coal Yard, Ningxia (detail), 81 from the series The Yellow River, 2011, archival pigment print, 107.95 x 132 cm. © Zhang Kechun. Courtesy of the artist. We thank JNBY Art Projects, D3E Art Limited, Chen Ping, and Stephanie Holmquist and Mark Allison for their generous contribution to the publication and distribution of Yishu. Vol. 15 No. -

Riding the Centaur Metaphor from Past to Present: Myth, Constellation and Non-Gendered Hybrid

IAFOR Journal of Literature & Librarianship Volume 8 – Issue 1 – Winter 2019 Riding the Centaur Metaphor from Past to Present: Myth, Constellation and Non-gendered Hybrid Jeri Kroll Flinders University, Australia 31 IAFOR Journal of Literature & Librarianship Volume 8 – Issue 1 – Winter 2019 Abstract Tracking the ancient centaur as myth and metaphor through cultural history to the twenty-first century reveals how humans have begun to reconceive animal-human relations. Its origins are open to question, but at least date from pre-classical and early Greek history, when nomadic tribes with superior horsemanship skills appeared. Associated with the astronomical constellation Centaurus, the centaur metaphor was initially gendered. The hybrid embodied human and equine qualities, both negative and positive (for example, the bestial classical centaur and the supra-human Spanish conquistador). After examining the history of the centaur metaphor as well as relationships between horses and humans in the pre-twentieth century Western literary tradition, this research focuses on five texts: Monty Roberts’ The Man Who Listens to Horses (2009); Tom McGuane’s Some Horses (2013); John Steinbeck’s The Red Pony (1945); Jane Smiley’s Horse Heaven (2000); and Gillian Mears’ Foal’s Bread (2011). It argues that contemporary nonfiction and fiction demonstrate a change in the way in which the metaphor has been used, reflecting a will to reshape relationships between species, grounded in empathy as well as respect for alternative communication strategies. The centaur metaphor as non-gendered hybrid appears when riders feel one with their horses through harmonious partnerships inherent in teamwork. They feel as if they have become the centaur, literalizing the metaphor within themselves. -

Results Book

THE REAL CHAMPIONS Thanks for making this years Dallas conditions, related neurological disorders White Rock Marathon a huge success! Your and learning disabilities. support of the Dallas White Rock Marathon Texas Scottish Rite Hospital provides T E x A directly benefits the lives 8 ongoing treatment to more of many yo~ng ~atients at SCOTTISH RITE HOSPITAL than 13,000 children a . Texas Scotnsh Rite •N-P.111• year - at no charge to their Hospital for Children. · IIMllll.all•• families. Since 1921, our Supported entirely through private efforts have dramatically impacted the lives donations, the hospital has emerged as one of more than 130,000 children around the of the nation's leading pediatric medical world. And thanks to your support, we'll centers for the treatment of orthopedic continue impacting lives for years to come. 2222 Welborn Street Dallas, Texas 75219-3993 (214) 559-5000 (800) 421-1121 www.tsrhc.org I Dear Runners: I December 10, 2000. The tlrirty-fust running of the Dallas was later accused of taking several shortcuts through the White Rock Marathon was one of America's last streets of Paris in order to secure the gold medal - was the marathons of the 20th century. How far our sport - and only participant wearing shorts rather than long pants. Dallas' flagship Marathon -- have come in this century! Seventy years later, Marathon running was slowly becom Marathons were a curiosity a hundred years ago. At the ing a mainstream sport for amateur athletes. Still, in Paris Olympics of 1900, only seven men competed in the 1971, when the Dallas White Rock Marathon was first Marathon and the winner - a French candy maker who established and named for one of America's most scenic urban lakes, only 82 dedicated dis tance runners - 80 men and two women - braved the 26.2-mile three loop course. -

Jean-Luc Moulène 简历

Jean-Luc Moulène 简历 Born in 1955, Reims, France. Lives & works in Normandy, France. EDUCATION 1979 Master’s degree in Arts Teaching, titled: “De la division des Arts”. Université Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne. 1978 BA in Literature at Sorbonne Paris 1. SOLO EXHIBITIONS (SELECTION) 2021 Mona – Museum of Old and New Art, Hobart, Tasmania, Australia. Casa Sao Roque, Porto, Portugal. 2020 Implicites & Objets, Galerie Chantal Crousel, Paris, France. 2019 L'art dans les chapelles, Chapelle Notre-Dame de Joie, le Gohazé, à Saint-Thuriau, Pontivy, France. More or Less Bone, SculptureCenter, New York, U.S.A. Jean-Luc Moulène, Bouboulina with Works on Paper, Miguel Abreu Gallery, New York, NY, U.S.A. La Vigie (extraits), Paris, 2004-2011 / ... , Galerie Chantal Crousel, Paris, France. 2018 Objets et faits, Synagogue de Delme, France. En angle mort, La Verrière, Fondation Hermès, Bruxelles, Belgique. Galerie Greta Meert, Brussels, Belgium. Un día que no estabas, Galeria Desiré Saint Phalle @ Galeria Marso, Mexico. 2017 10 RUE CHARLOT, 75003 PARIS +33 1 42 77 38 87 | CROUSEL.COM [email protected] The Secession Knot (5.1), Secession, Vienna, Austria. Hole, Bubble, Bump., Miguel Abreu Gallery, New York, U.S.A. 2016 Ce fut une belle journée., Galerie Chantal Crousel, Paris, France. Jean-Luc Moulène, Musée National d'Art Moderne, Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris, France. Jean-Luc Moulène: Larvae and Ghosts, Thomas Dane Gallery, London, U.K. 2015 Verde Azul Blanco Negro Rojo, Torre de los Vientos, Mexico D.F., Mexico. Il était une fois, Villa Medici, Roma, Italy. Documents & Opus, Kunstverein, Hannover, Germany. 2014 Miguel Abreu Gallery, New York, U.S.A. -

M.E. VIBRATIONS the Mechanical Engineering Department Alumni Newsletter March 2005

M.E. VIBRATIONS The Mechanical Engineering Department Alumni Newsletter March 2005 Welcome to the latest issue of Vibrations! The academic year will be coming to a close soon, with fewer than two months until graduation (May 22). There is much to accomplish by both students and faculty as we near completion of Ron Dougherty, Professor and Chair the school year and watch another group of seniors [and graduate students] reach engineering maturity and head out into the world. The seniors are working hard on their projects, whether it’s the Formula Vehicle, the explosion containment system for bomb-laden luggage carried on board a commercial airliner, the ergonomic improvement of an assembly-line-type of work station, or the system to test for damage caused by full-sized forklifts colliding with plastic pallets for large/heavy merchandise transport. Graduate students are completing their research with biomechanical knee simulators, intelligently designed/controlled robots, fundamental finite element code development, and space thermal systems. These soon-to-be-graduates are preparing to leave and tackle new challenges. Or, whether it’s one of our student athletes such as Lindsey Morris from the volleyball team, Chris Veit who is one the students who “sports” the Jayhawk mascot outfit at various sporting/KU events, Kelly Warrick who plays trombone for the pep band, Kelley Briant who will be enrolling in law school, James Winblad who’s going to medical school, or a number of other students who will be taking positions with Ford, Black & Veatch, Boeing, Whirlpool, the armed services, business schools, educational institutions, or graduate schools - - we will surely miss them.