Riding the Centaur Metaphor from Past to Present: Myth, Constellation and Non-Gendered Hybrid

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Introducing the 10 Shortlisted Ghetto Film School Fellows for the Inaugural Deutsche Bank Frieze Los Angeles Film Award 2020

Frieze Los Angeles Press Release December 19, 2019 Introducing the 10 Shortlisted Ghetto Film School Fellows for the Inaugural Deutsche Bank Frieze Los Angeles Film Award 2020 Today Frieze and Deutsche Bank announce the ten shortlisted fellows that will headline the inaugural Deutsche Bank Frieze Los Angeles Film Award. Presented in partnership with award-winning, non-profit film academy Ghetto Film School (GFS), the initiative offers a platform and development program for ten emerging, Los Angeles-based filmmakers aged 20-34 years old. Frieze Los Angeles takes place February 14 – 16, 2020 at Paramount Pictures Studios in Hollywood. Launched in 2019, Frieze Los Angeles brings together more than 70 galleries from around the world and is supported by global lead partner Deutsche Bank for the second consecutive year. The ten shortlisted fellows are as follows: Danielle Boyd, Mya Dodson, Michelle Jihyon Kim, Nabeer Khan, Silvia Lara, Alima Lee, Timothy Offor, Toryn Seabrooks, Noah Sellman and Nicole L. Thompson. The recipient of the award, selected by a jury of leading art and entertainment figures including Doug Aitken, Shari Frilot, Jeremy Kagan, Sam Taylor Johnson and Hamza Walker will be announced at a ceremony on February 13 at Paramount Pictures Theatre and receive a $10,000 prize. Selected from an open call throughout Los Angeles, the ten shortlisted fellows completed an intensive three-month program at GFS each producing a short film in response to Los Angeles’ vibrant art, culture and social landscape. The resulting 10 short films will be screened at the Paramount Pictures Theatre throughout the fair, February 14-16, 2020. -

Ovid's Metamorphoses Translated by Anthony S. Kline1

OVID'S METAMORPHOSES TRANSLATED BY 1 ANTHONY S. KLINE EDITED, COMPILED, AND ANNOTATED BY RHONDA L. KELLEY Figure 1 J. M. W. Turner, Ovid Banished from Rome, 1838. 1 http://ovid.lib.virginia.edu/trans/Ovhome.htm#askline; the footnotes are the editor’s unless otherwise indicated; for clarity’s sake, all names have been standardized. The Metamorphoses by the Roman poet Publius Ovidius Naso (Ovid) was published in 8 C.E., the same year Ovid was banished from Rome by Caesar Augustus. The exact circumstances surrounding Ovid’s exile are a literary mystery. Ovid himself claimed that he was exiled for “a poem and a mistake,” but he did not name the poem or describe the mistake beyond saying that he saw something, the significance of which went unnoticed by him at the time he saw it. Though Ovid had written some very scandalous poems, it is entirely possible that this satirical epic poem was the reason Augustus finally decided to get rid of the man who openly criticized him and flouted his moral reforms. In the Metamorphoses Ovid recounts stories of transformation, beginning with the creation of the world and extending into his own lifetime. It is in some ways, Ovid’s answer to Virgil’s deeply patriotic epic, The Aeneid, which Augustus himself had commissioned. Ovid’s masterpiece is the epic Augustus did not ask for and probably did not want. It is an ambitious, humorous, irreverent romp through the myths and legends and even the history of Greece and Rome. This anthology presents Books I and II in their entirety. -

CHROME COULD BE BACK for >18 PEGASUS, and WHY NOT?

TUESDAY, JANUARY 31, 2017 CLYDE RICE PASSES AWAY CHROME COULD BE BACK by Jessica Martini FOR >18 PEGASUS, Clyde Rice, the patriarch of a far-ranging family of trainers, jockeys and consignors, passed away Monday at his home in AND WHY NOT? Anthony, Florida. He was 79. A native of Antigo, Wisconsin, Rice was a high school teacher before deciding to pursue a career in the horse industry. Several times leading trainer at Penn National in the 1970s and 80s, he became a pioneer in the yearling-to-juvenile pinhooking market, raising horses at his Indian Prairie Ranch in Anthony. Rice grew up alongside future Hall of Fame trainer D. Wayne Lukas and the two men shared a passion for horses. AHe was a dear friend and I can=t tell you what a great horseman he was,@ Lukas recalled Monday. AWe grew up about a half-mile apart and spent our whole boyhoods with these horses and traveling miles and miles to sales and shows. He was special and he had a great knack, a really good eye for a horse.@ Cont. p4 IN TDN EUROPE TODAY California Chrome in Gulfstream paddock | A Coglianese STEWARD’S CUP GOES TO PARAGON by Bill Finley Helene Paragon (Fr) (Polan {Fr}), formerly trained in Spain, Ask someone in horse racing why things are done a certain landed the G1 Stewards’ Cup at Sha Tin on Monday. Click or way and the answer is usually Abecause that=s the way it=s tap here to go straight to TDN Europe. always been done.@ It=s a terrible answer and speaks to an industry so stuck in the past that it's afraid to try anything new and innovative. -

106June Crossword 2019 Astrology

Vic Skeptics June 2019 Crossword Theme – Astrology by Roy Arnott & Ken Greatorex (With standard and cryptic clues) 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 Standard clues: pp 2 – 4 Cryptic clues: pp 5 – 7 Solution: p 8 2 STANDARD CLUES ACROSS: 4. A chart of the heavens cast for a particular moment in time, as seen from a particular place on the Earth's surface [9] 7. In astrology, a “killing planet” which cuts off the light and influence of nearby bodies [9] 8. A time of equal day and equal night occurring twice a year [7] 11. The only inanimate sign in the Zodiac [5] 12. Procurer [4] 13. Rims [5] 15. Existing at the beginning [7] 16. The Water Carrier [8] 18. The convention that the Earth, rather than the Sun is at the centre of the Solar System [9] 19. Regularly and predictably repeated [6] 22. Proceed [2] 23. Written text of a play or film [6] 26. Description of the moon when more than half of its illuminated surface is visible [7] 28. The Fish (derived from the ichthyocentaurs, who in Greek mythology aided Aphrodite when she was born from the sea) [6] 30. Fire, water, air & earth collectively in astrology; They relate to three of the signs of the zodiac each [8] 31. -

Frieze Los Angeles: Announcing Highlights for the Inaugural Edition

Frieze Los Angeles Press Release January 23, 2019 Frieze Los Angeles: Announcing Highlights for the Inaugural Edition Hosted at Paramount Pictures Studios, Including Special Gallery Presentations and Curated Artist Projects, Talks and Film More than 70 invited galleries will take part in the first Frieze Los Angeles – including a special selection of emerging spaces from the city – presenting a global cross-section of today’s most significant and exciting artists and creating an exceptional opportunity for collecting and discovery The curated program will celebrate the unique creative spirit of Los Angeles. Artist projects, talks, films, restaurants and experiments in patronage and activism, will transform the movie set backlot of Paramount Pictures Studios into a symbolic cityscape where art is at the center of civic life Frieze today announces the programs and highlights for the launch edition of Frieze Los Angeles. The new annual contemporary art fair will feature more than 70 L.A.-based and international galleries, alongside a site-specific program of talks, music and commissioned artist projects. Organized in collaboration with leading curators and working closely with venue partner Paramount Pictures Studios, Frieze Los Angeles joins Frieze New York, Frieze London and Frieze Masters at the forefront of the international art fair calendar, celebrating Los Angeles’ position as a global arts center and destination. Global lead partner Deutsche Bank will support the inaugural edition of Frieze Los Angeles, continuing a shared commitment to discovery and artistic excellence. Taking place in a bespoke structure designed by Kulapat Yantrasast, Frieze Los Angeles is led by Victoria Siddall (Director, Frieze Fairs) and Bettina Korek (Executive Director, Frieze Los Angeles). -

Duke Certamen 2018 Intermediate Division Round 1

DUKE CERTAMEN 2018 INTERMEDIATE DIVISION ROUND 1 1. Which emperor reformed the Praetorian Guard, replacing it with his loyal provincial troops upon his ascension? SEPTIMIUS SEVERUS B1: At which city did his troops declare Severus emperor? CARNUNTUM B2: Which of his two main rivals did Severus defeat first? PESCENNIUS NIGER 2. Differentiate in meaning between lupus and lepus. WOLF and HARE / RABBIT B1: Give a synonym for the animal bōs. VACCA / VITULA B2: Give either Latin animal from which we derive “porpoise.” PORCUS or PISCIS 3. Europa, Minos, Procris, and Amphitryon all owned what infallible hunting hound? LAELAPS B1: What husband of Procris tried to use Laelaps to hunt the Teumessian vixen? CEPHALUS B2: According to Hyginus, Cephalus was the father of what Ithacan man? LAERTES 4. Give the Latin and English for the abbreviation Rx. RECIPE – TAKE B1: If your prescription label tells you to take your medication prn., how often should you take it? AS NEEDED B2: Give the Latin and English for the abbreviation gtt. GUTTAE – DROPS 5. Translate the following sentence from Latin to English: Mulierēs quae ducēs factae erant fortiōrēs quam omnēs erant. THE WOMEN WHO HAD BECOME / BEEN MADE LEADERS WERE STRONGER / BRAVER THAN ALL B1: Translate this sentence: Hannibal ipse cum hīs mulieribus pūgnāre nōluit. HANNIBAL HIMSELF DID NOT WANT TO FIGHT (WITH) THESE WOMEN B2: Finally translate: Urbe servātā dūcibus triumphī ā cīvibus datī sunt. AFTER THE CITY WAS SAVED / WITH THE CITY HAVING BEEN SAVED, TRIUMPHS WERE GIVEN TO/FOR THE LEADERS BY THE CITIZENS 6. What son of Cephissus and Liriope fell in love with his own reflection, died of starvation, and was turned into a flower? NARCISSUS B1. -

Frieze Los Angeles Press Release September 12, 2018

Frieze Los Angeles Press Release September 12, 2018 Frieze Los Angeles: Announcing Galleries and Curators for the Inaugural Edition Around 70 galleries will take part in the first Frieze Los Angeles, including a special selection of emerging spaces from Los Angeles Curator Hamza Walker to program Frieze Talks and Frieze Music Frieze today announces the 68 participating galleries in the inaugural edition of Frieze Los Angeles. The new annual contemporary art fair will feature a site-specific program of talks, music and commissioned artist projects organized in collaboration with leading curators. Opening at Paramount Pictures Studios in Hollywood from February 14 through February 17, 2019, Frieze Los Angeles will join Frieze New York, Frieze London and Frieze Masters at the forefront of the international art fair calendar, celebrating Los Angeles’ position as a global arts center and destination. Taking place in a bespoke structure designed by Kulapat Yantrasast, Frieze Los Angeles is led by Bettina Korek (Executive Director, Frieze Los Angeles) working with Victoria Siddall (Director, Frieze Fairs). Joining them is the newly announced curator of Frieze Talks and Music, Hamza Walker (Executive Director, LAXART), and Ali Subotnick, who will commission Frieze Projects and Frieze Film. Also announced today Frieze Los Angeles will be supported by Deutsche Bank, global lead partner for Frieze London, Frieze Masters and Frieze New York. Victoria Siddall said, “The extremely positive reaction to Frieze Los Angeles from galleries is testament to the importance of this city which is so rich in great artists, museums, galleries, and art schools. I am thrilled with the response we have had and the strength of the exhibitor list, which includes exceptional contemporary art galleries from around the world as well as leading established and emerging spaces from LA. -

M. Paul Friedberg Reflections

The Cultural Landscape Foundation Pioneers of American Landscape Design ___________________________________ M. PAUL FRIEDBERG ORAL HISTORY REFLECTIONS ___________________________________ Howard Abel Jim Balsley Charlotte Frieze Bernard Jacobs Sonja Johansson Signe Nielson Nicholas Quennell Lee Weintraub Mingkuo Yu © 2009 The Cultural Landscape Foundation, all rights reserved. May not be used or reproduced without permission. Reflections on M. Paul Friedberg from Howard Abel April 2009 I worked with Paul from 1961-1964 with a 6 month Army Reserve tour in the middle. When I began there were four of us in the office. The office was in an apartment on 86th Street and Madison Avenue with Paul working out of the kitchen and Walter Diakow, his partner, and Phil Loman and myself in the converted living room. Paul used the back bedroom as his living quarters. I had been out of school for about six months and had worked for a traditional landscape architectural firm before joining Paul's office. The pace and excitement were electrifying. We worked on lots of small projects, mainly housing with Paul wanting to try ten new ideas for each project. He usually got at least one but at the end of the tenth project he'd have his ten and just kept on going. His vision on how urban space should be used and defined was quite different from the then thinking current attitude. His work seemed to be intuitive and emotional usually thinking how people would fit into the landscape. Proportion, scale and use of material took on a completely different meaning. I always marveled that he was willing to try to do anything. -

![World History--Part 1. Teacher's Guide [And Student Guide]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1845/world-history-part-1-teachers-guide-and-student-guide-2081845.webp)

World History--Part 1. Teacher's Guide [And Student Guide]

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 462 784 EC 308 847 AUTHOR Schaap, Eileen, Ed.; Fresen, Sue, Ed. TITLE World History--Part 1. Teacher's Guide [and Student Guide]. Parallel Alternative Strategies for Students (PASS). INSTITUTION Leon County Schools, Tallahassee, FL. Exceptibnal Student Education. SPONS AGENCY Florida State Dept. of Education, Tallahassee. Bureau of Instructional Support and Community Services. PUB DATE 2000-00-00 NOTE 841p.; Course No. 2109310. Part of the Curriculum Improvement Project funded under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), Part B. AVAILABLE FROM Florida State Dept. of Education, Div. of Public Schools and Community Education, Bureau of Instructional Support and Community Services, Turlington Bldg., Room 628, 325 West Gaines St., Tallahassee, FL 32399-0400. Tel: 850-488-1879; Fax: 850-487-2679; e-mail: cicbisca.mail.doe.state.fl.us; Web site: http://www.leon.k12.fl.us/public/pass. PUB TYPE Guides - Classroom - Learner (051) Guides Classroom Teacher (052) EDRS PRICE MF05/PC34 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Academic Accommodations (Disabilities); *Academic Standards; Curriculum; *Disabilities; Educational Strategies; Enrichment Activities; European History; Greek Civilization; Inclusive Schools; Instructional Materials; Latin American History; Non Western Civilization; Secondary Education; Social Studies; Teaching Guides; *Teaching Methods; Textbooks; Units of Study; World Affairs; *World History IDENTIFIERS *Florida ABSTRACT This teacher's guide and student guide unit contains supplemental readings, activities, -

Unbridled Achievement SMU 2011-12 ANNUAL REPORT TABLE of CONTENTS

UNBRIDLED ACHIEVEMENT SMU 2011-12 ANNUAL REPORT TABLE OF CONTENTS 4 | SMU BOARD OF TRUSTEES 2011–12 5 | LETTER FROM THE CHAIR OF THE BOARD OF TRUSTEES 6 | SMU ADMINISTRATION 2011–12 7 | LETTER FROM THE PRESIDENT 8 | THE SECOND CENTURY CELEBRATION 14 | PROGRESS REPORT Student Quality Faculty and Academic Excellence Campus Experience 38 | FINANCIAL REPORT Consolidated Financial Statements Expenditures Toward Strategic Goals Endowment Report Campaign Update Yearly Giving 48 | HONOR ROLLS Second Century Campaign Donors New Endowment Donors New Dallas Hall Society Members President’s Associates Corporations, Foundations and Organizations Hilltop Society 2 | SMU.EDU/ANNUALREPORT In 2011-12 SMU celebrated the second year of the University’s centennial commemoration period marking the 100th anniversaries of SMU’s founding and opening. The University’s progress was marked by major strides forward in the key areas of student quality, faculty and academic excellence and the campus experience. The Second Century Campaign, the largest fundraising initiative in SMU history, continued to play an essential role in drawing the resources that are enabling SMU to continue its remarkable rise as a top educational institution. By the end of the fiscal year, SMU had received commitments for more than 84 percent of the campaign’s financial goals. Thanks to the inspiring support of alumni, parents and friends of the University, SMU is continuing to build a strong foundation for an extraordinary second century on the Hilltop. SMU BOARD OF TRUSTEES 2011-12 LETTER FROM THE CHAIR OF THE BOARD OF TRUSTEES Caren H. Prothro, Chair Gerald J. Ford ’66, ’69 Helmut Sohmen ’66 Civic and Philanthropic Leader Diamond A Ford Corporation BW Corporation Limited Michael M. -

The New World Mythology in Italian Epic Poetry: 1492-1650

THE NEW WORLD MYTHOLOGY IN ITALIAN EPIC POETRY: 1492-1650 by CARLA ALOÈ A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of Italian Studies School of Languages, Cultures, Art History and Music College of Arts and Law University of Birmingham September 2015 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT My thesis explores the construction of the New World mythology as it appears in early modern Italian epic poems. It focuses on how Italian writers engage with and contribute to this process of myth-creation; how the newly created mythology relates to the political, social and cultural context of the time; and investigates extent to which it was affected by the personal agendas of the poets. By analysing three New World myths (Brazilian Amazons, Patagonian giants and Canadian pygmies), it provides insights into the perception that Italians had of the newly discovered lands in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries, as well as providing a greater understanding of the role that early modern Italy had in the ‘invention’ of the Americas. -

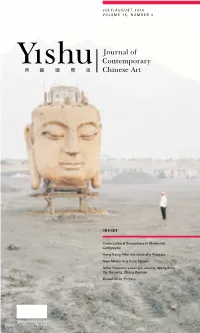

July/August 2016 Volume 15, Number 4 Inside

J U L Y / A U G U S T 2 0 1 6 VOLUME 15, NUMBER 4 INSIDE Cross-Cultural Encounters in Modernist Calligraphy Hong Kong After the Umbrella Protests New Media Arts from Taiwan Artist Features: susan pui san lok, Wang Bing, Xie Nanxing, Zhang Kechun Buried Alive: Preface US$12.00 NT$350.00 PRINTED IN TAIWAN 6 VOLUME 15, NUMBER 4, JULY/AUGUST 2016 CONTENTS 29 2 Editor’s Note 4 Contributors 6 Lines in Translation: Cross-Cultural Encounters in Modernist Calligraphy, Early 1980s–Early 1990s Shao-Lan Hertel 53 29 Spots, Dust, Renderings, Picabia, Case Notes, Flavour, Light, Sound, and More: Xie Nanxing’s Creations Carol Yinghua Lu 45 Zhang Kechun: Photographing "China’s Sorrow" Adam Monohon 53 Hong Kong After the Umbrella Protests John Batten 65 65 RoCH Redux Alice Ming Wai Jim 71 Wuxia Makes Me Nervous Henry Tsang 76 New and Greater Prospects Beyond the Frame: New Media Arts from Taiwan Claudia Bohn-Spector 81 In and Out of the Dark with Extreme Duration: Documenting China One Person at a Time in 76 the Films of Wang Bing Brian Karl 91 Buried Alive: Preface Lu Huanzhi 111 Chinese Name Index Cover: Zhang Kechun, Buddha in a Coal Yard, Ningxia (detail), 81 from the series The Yellow River, 2011, archival pigment print, 107.95 x 132 cm. © Zhang Kechun. Courtesy of the artist. We thank JNBY Art Projects, D3E Art Limited, Chen Ping, and Stephanie Holmquist and Mark Allison for their generous contribution to the publication and distribution of Yishu. Vol. 15 No.