Association Between Media Exposure and Family Planning in Myanmar

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Burma Watching: a Retrospective

Griffith Asia Institute Regional Outlook Burma Watching: A Retrospective Andrew Selth About the Griffith Asia Institute The Griffith Asia Institute produces innovative, interdisciplinary research on key developments in the politics, economics, societies and cultures of Asia and the South Pacific. By promoting knowledge of Australia’s changing region and its importance to our future, the Griffith Asia Institute seeks to inform and foster academic scholarship, public awareness and considered and responsive policy making. The Institute’s work builds on a 41 year Griffith University tradition of providing cutting- edge research on issues of contemporary significance in the region. Griffith was the first University in the country to offer Asian Studies to undergraduate students and remains a pioneer in this field. This strong history means that today’s Institute can draw on the expertise of some 50 Asia–Pacific focused academics from many disciplines across the university. The Griffith Asia Institute’s ‘Regional Outlook’ papers publish the institute’s cutting edge, policy-relevant research on Australia and its regional environment. They are intended as working papers only. The texts of published papers and the titles of upcoming publications can be found on the Institute’s website: www.griffith.edu.au/asiainstitute ‘Burma Watching: A Retrospective’, Regional Outlook Paper No. 39, 2012. About the Author Andrew Selth Andrew Selth is an Adjunct Research Fellow at the Griffith Asia Institute. He has been studying international security issues and Asian affairs for 40 years, as a diplomat, strategic intelligence analyst and research scholar. He has published four books and more than 50 other peer-reviewed works, most of them about Burma and related subjects. -

The Journal of the Walters Art Museum

THE JOURNAL OF THE WALTERS ART MUSEUM VOL. 73, 2018 THE JOURNAL OF THE WALTERS ART MUSEUM VOL. 73, 2018 EDITORIAL BOARD FORM OF MANUSCRIPT Eleanor Hughes, Executive Editor All manuscripts must be typed and double-spaced (including quotations and Charles Dibble, Associate Editor endnotes). Contributors are encouraged to send manuscripts electronically; Amanda Kodeck please check with the editor/manager of curatorial publications as to compat- Amy Landau ibility of systems and fonts if you are using non-Western characters. Include on Julie Lauffenburger a separate sheet your name, home and business addresses, telephone, and email. All manuscripts should include a brief abstract (not to exceed 100 words). Manuscripts should also include a list of captions for all illustrations and a separate list of photo credits. VOLUME EDITOR Amy Landau FORM OF CITATION Monographs: Initial(s) and last name of author, followed by comma; italicized or DESIGNER underscored title of monograph; title of series (if needed, not italicized); volume Jennifer Corr Paulson numbers in arabic numerals (omitting “vol.”); place and date of publication enclosed in parentheses, followed by comma; page numbers (inclusive, not f. or ff.), without p. or pp. © 2018 Trustees of the Walters Art Gallery, 600 North Charles Street, Baltimore, L. H. Corcoran, Portrait Mummies from Roman Egypt (I–IV Centuries), Maryland 21201 Studies in Ancient Oriental Civilization 56 (Chicago, 1995), 97–99. Periodicals: Initial(s) and last name of author, followed by comma; title in All Rights Reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced without the written double quotation marks, followed by comma, full title of periodical italicized permission of the Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, Maryland. -

Refugees from Burma Acknowledgments

Culture Profile No. 21 June 2007 Their Backgrounds and Refugee Experiences Writers: Sandy Barron, John Okell, Saw Myat Yin, Kenneth VanBik, Arthur Swain, Emma Larkin, Anna J. Allott, and Kirsten Ewers RefugeesEditors: Donald A. Ranard and Sandy Barron From Burma Published by the Center for Applied Linguistics Cultural Orientation Resource Center Center for Applied Linguistics 4646 40th Street, NW Washington, DC 20016-1859 Tel. (202) 362-0700 Fax (202) 363-7204 http://www.culturalorientation.net http://www.cal.org The contents of this profile were developed with funding from the Bureau of Population, Refugees, and Migration, United States Department of State, but do not necessarily rep- resent the policy of that agency and the reader should not assume endorsement by the federal government. This profile was published by the Center for Applied Linguistics (CAL), but the opinions expressed herein do not necessarily reflect positions or policies of CAL. Production supervision: Sanja Bebic Editing: Donald A. Ranard Copyediting: Jeannie Rennie Cover: Burmese Pagoda. Oil painting. Private collection, Bangkok. Design, illustration, production: SAGARTdesign, 2007 ©2007 by the Center for Applied Linguistics The U.S. Department of State reserves a royalty-free, nonexclusive, and irrevocable right to reproduce, publish, or otherwise use, and to authorize others to use, the work for Government purposes. All other rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, in any form or by any means, without permission in writing from the publisher. All inquiries should be addressed to the Cultural Orientation Resource Center, Center for Applied Linguistics, 4646 40th Street, N.W., Washington, D.C. 20016. -

Myanmar (Burma): a Reading Guide Andrew Selth

Griffith Asia Institute Research Paper Myanmar (Burma): A reading guide Andrew Selth i About the Griffith Asia Institute The Griffith Asia Institute (GAI) is an internationally recognised research centre in the Griffith Business School. We reflect Griffith University’s longstanding commitment and future aspirations for the study of and engagement with nations of Asia and the Pacific. At GAI, our vision is to be the informed voice leading Australia’s strategic engagement in the Asia Pacific— cultivating the knowledge, capabilities and connections that will inform and enrich Australia’s Asia-Pacific future. We do this by: i) conducting and supporting excellent and relevant research on the politics, security, economies and development of the Asia-Pacific region; ii) facilitating high level dialogues and partnerships for policy impact in the region; iii) leading and informing public debate on Australia’s place in the Asia Pacific; and iv) shaping the next generation of Asia-Pacific leaders through positive learning experiences in the region. The Griffith Asia Institute’s ‘Research Papers’ publish the institute’s policy-relevant research on Australia and its regional environment. The texts of published papers and the titles of upcoming publications can be found on the Institute’s website: www.griffith.edu.au/asia-institute ‘Myanmar (Burma): A reading guide’ February 2021 ii About the Author Andrew Selth Andrew Selth is an Adjunct Professor at the Griffith Asia Institute, Griffith University. He has been studying international security issues and Asian affairs for 45 years, as a diplomat, strategic intelligence analyst and research scholar. Between 1974 and 1986 he was assigned to the Australian missions in Rangoon, Seoul and Wellington, and later held senior positions in both the Defence Intelligence Organisation and Office of National Assessments. -

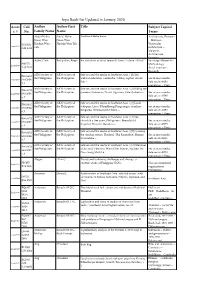

Inya Book-List Updated in January 2020

Inya Book-list Updated in January 2020 Acces Call Author Author First Title Subject Topical s. # No. Family Name Name Terms Abdul Halim Abdul Halim Traditional Malay house Architecture, Domestic Nasir, Wan Nasir, Wan -- Malaysia. NA7436 . Hashim Wan Hashim Wan Teh. Vernacular Inya-0335 A24 1996 Teh. architecture -- Malaysia. Architecture, Domestic. Adler; Clark Emily Stier; Roger An invitation to social research : how it's done / 4th ed Sociology--Research-- HM571 . Methodology. Inya-0399 A35 2011 Social sciences-- Research-- AIDS Society of AIDS Society of Safe sex and the media in Southeast Asia. / [1] Sex Methodology. P96.S452 the Philippines. the Philippines. without substance, Cambodia / Chhay Sophal, Steven Sex in mass media. Inya-0283 S68 2004 Pak -- Safe sex in AIDS v.1 prevention -- Press AIDS Society of AIDS Society of Safe sex and the media in Southeast Asia. / [2] Riding the coverage -- Southeast P96.S452 the Philippines. the Philippines. paradox, Indonesia / Nurul Agustina, Irwan Julianto -- Asia.Sex in mass media. Inya-0410 S68 2004 SexualSafe sex health in AIDS -- Press v.2 coverageprevention -- --Southeast Press AIDS Society of AIDS Society of Safe sex and the media in Southeast Asia. / [3] Loud Asia.coverage -- Southeast P96.S452 the Philippines. the Philippines. whispers, Laos / Khamkhong Kongvongsa, Somkiao Asia.Sex in mass media. Inya-0411 S68 2004 Kingsada, Phonesavanh Thikeo -- SexualSafe sex health in AIDS -- Press v.3 coverageprevention -- --Southeast Press AIDS Society of AIDS Society of Safe sex and the media in Southeast Asia. / [4] Sex, Asia.coverage -- Southeast P96.S452 the Philippines. the Philippines. church & a free press, Philippines / Reynaldo H. -

Mekong River

CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION The Mekong is one of the world’s great rivers, sustaining million of people with its rich fisheries and fertile flood plains. The Mekong River basin is home to over 60 million people from more than 100 different ethnic groups, most of whom are heavily dependent on the river’s natural 10.14457/KU.the.2007.3resources for their livelihoods. The river itself is among the richest in the world in terms of its abundance of aquatic biodiversity, supporting 1,300 species of fish. เมื่อ 06/10/2564 06:02:55 However, ambitious development projects for the region are sometimes poorly planned. Moreover, they can become major obstacles to sustainable management of the river basin and could adversely affect the socio-economic balance of the whole region and the livelihoods of its people. The mass media is a crucial tool for the guidance of development processes. The media both receives and sends messages. Most of the time, we see the media as the message sender, news creator or even the speaker of the issues. It’s true that media has the power to draw the attention of people towards the specific issues. The Mekong has been a “hot spot” for the news. The local, regional and international media all keep their eyes on developments in the Mekong River Basin, and this is having an impact. For example, the Mekong Rapids Blasting Project has been temporarily halted in the Thai part of the Mekong River because of public opposition to the project and boundary demarcation between Thailand and Laos. -

Political Will: Will: Political a Short Introduction a Short

POLITICAL WILL: A SHORT INTRODUCTION POLITICAL WILL: A SHORT POLITICAL WILL: A SHORT INTRODUCTION CASE STUDY - BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA CASE STUDY - BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA Edited by Dino Abazović Asim Mujkić Dino Abazović and Asim Mujkić (editor) POLITICAL WILL: A SHORT INTRODUCTION CASE STUDY - BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA Sarajevo, 2015. Title: Political will: a short introduction Case study - Bosnia and Herzegovina Original title: Kratki uvod u problem političke volje: studija slučaja Bosne i Hercegovine Editors: Dino Abazović Asim Mujkić Publisher: Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung (FES) Kupreška 20 71 000 Sarajevo Bosnia and Herzegovina Tel. : +387 (0)33 722 010 E-mail: [email protected] www.fes.ba Responsible: Judith Illerhues Proofreading: Zinaida Lakić DTP: Filip Andronik CIP - Katalogizacija u publikaciji Nacionalna i univerzitetska biblioteka Bosne i Hercegovine, Sarajevo 321.01(082) POLITICAL will: a short introduction case study - Bosnia and Herzegovina / [Dino Abazović, Asim Mujkić, editors]. - Sarajevo : Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung, 2015. - 284 str. : graf. prikazi ; 21 cm Prijevod djela: Kratki uvod u problem političke volje. - Bibliografija i bilješke uz tekst. ISBN 978-9958-884-41-2 COBISS.BH-ID 22260230 Attitudes, opinions and conclusions expressed in this publication do not necessarily express attitudes of the Friedrich-Ebert Foundation. The Friedrich-Ebert Foundation does not vouch for the accuracy of the data stated in this publication.commercial use of all media published by the Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung (FES) is not permitted without the written consent of the FES. POLITICAL WILL: A SHORT INTRODUCTION CASE STUDY - BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA Sarajevo, 2015. Contents FOREWORD.................................................................................... 7 Asim Mujkić AN INTRODUCTION TO POLITICAL WILL ....................................... 11 Jelena Brkić Šmigoc POLITICAL WILL FOR POLITICAL BEHAVIOUR ................................ -

Book List for Download.Xlsx

Inya Book-list Updated in January 2019 Accession Call Aurthor Family Author First Title Subject Topical Terms No. No. Name Name traditional Malay house Architecture, Domestic -- Malaysia. Vernacular architecture -- Malaysia. Abdul Halim Nasir, Abdul Halim Nasir, NA7436 Architecture, Domestic. Inya-0335 Wan Hashim Wan Wan Hashim Wan .A24 1996 Teh. Teh. An invitation to social research : how Sociology--Research--Methodology. HM571 Inya-0399 Adler; Clark Emily Stier; Roger it's done / 4th ed Social sciences--Research-- .A35 2011 Methodology. Safe sex and the media in Southeast P96.S452 Sex in mass media. AIDS Society of the AIDS Society of the Asia. / [1] Sex without substance, Inya-0283 S68 2004 Safe sex in AIDS prevention -- Press Philippines. Philippines. Cambodia / Chhay Sophal, Steven Pak - coverage -- Southeast Asia. v.1 - Sexual health -- Press coverage -- Southeast Asia. Safe sex and the media in Southeast P96.S452 Sex in mass media. AIDS Society of the AIDS Society of the Asia. / [2] Riding the paradox, Inya-0410 S68 2004 Safe sex in AIDS prevention -- Press Philippines. Philippines. Indonesia / Nurul Agustina, Irwan v.2 coverage -- Southeast Asia. Julianto -- Sexual health -- Press coverage -- Southeast Asia. Safe sex and the media in Southeast Sex in mass media. P96.S452 Asia. / [3] Loud whispers, Laos / AIDS Society of the AIDS Society of the Safe sex in AIDS prevention -- Press Inya-0411 S68 2004 Khamkhong Kongvongsa, Somkiao Philippines. Philippines. coverage -- Southeast Asia. v.3 Kingsada, Phonesavanh Thikeo -- Sexual health -- Press coverage -- Southeast Asia. Safe sex and the media in Southeast Sex in mass media. P96.S452 Asia. / [4] Sex, church & a free press, AIDS Society of the AIDS Society of the Safe sex in AIDS prevention -- Press Inya-0412 S68 2004 Philippines / Reynaldo H. -

Translating Rule of Law to Myanmar

Translating Rule of Law to Myanmar: Intermediaries’ Power and Influence A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The Australian National University Kristina Simion School of Regulation and Global Governance (RegNet) Australian National University April, 2018 © Copyright by Kristina Simion, 2018 All Rights Reserved Candidate’s declaration This thesis contains no material that has been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma in any university. To the best of the author‘s knowledge, it contains no material previously published or written by another person, except where due reference is made in the text. 9 April 2018 Kristina Simion Date Word count: 99 814 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am grateful to many people for supporting me throughout this thesis. I am especially indebted to my primary supervisor, Veronica Taylor, who devoted much time and energy to this project. As well as your constant encouragement and support, your contributions challenged me and helped me influence my ideas into a coherent form. Thanks for keeping me interested in this field with your creativity and originality in thought. I was also very lucky to have the support of my thesis panel advisers Martin Krygier, Nick Cheesman, and Morten Pedersen who provided thorough advice on my writing, encouraging discussions, and friendly support in the field when I needed it the most. I have been fortunate to share my PhD journey with fellow colleagues at the School of Regulation and Global Governance (RegNet), each of whom helped make the experience an enjoyable one. Robyn Holder and Therese Pearce Laanela, thanks for being great room-mates and friends. -

MYANMAR Disaster Management Reference Handbook

MYANMAR Disaster Management Reference Handbook March 2020 Acknowledgements CFE-DM would like to thank the following people for providing support and valuable inputs to this document: Dr. Sithu Pe Thein Christine Rivera Torres Alan Aoki Ranya Ghadban Cover and section photo credits Cover Photo: Bagan Myanmar by Yoshitaka Ando. 2 May 2017. CC https://flickr.com/photos/jenlung-box/34587536486 Country Overview Section Photo: Young Monk in the Window. Photo courtesy of Christine Rivera Torres. 8 February 2020 Disaster Overview Section Photo: Fighting Floods in Myanmar by EU/ECHO/Pierre Prakash. Civil Protections Humanitarian Aid. 8 September 2015. https://flickr.com/photos/eu_echo/30145370151 Organizational Structure for Disaster Management Section Photo: Yangon by Rayesh-India. 4 October 2014. CC https://flickr.com/photos/pamnani/15437975075 Infrastructure Section Photo: Inle Lake, Myanmar Fisherman Rowing with Food so Hands are Free to Fish. Photo courtesy of Christine Rivera Torres. 8 February 2020 Health Section Photo: Fighting Floods in Myanmar by EU/ECHO/Pierre Prakash. Civil Protections Humanitarian Aid. 8 September 2015. https://flickr.com/photos/eu_echo/30196045456 Women, Peace, and Security Section Photo: Burmese Woman Wearing Thanaka. Photo courtesy of Christine Rivera Torres. 8 February 2020 Conclusion Section Photo: Sulamani Phaya Temple With Local Nuns. Photo courtesy of Christine Rivera Torres. 8 February 2020 Appendices Section Photo: Mandalay Kuthodaw Pagoda – World’s Largest Book. Photo courtesy of Christine Rivera Torres. -

สื่อมวลชนประเทศเมียนมาร์ Journalists in Myanmar

วารสารวิชาการ คณะวิทยาการจัดการ มหาวิทยาลัยราชภัฏมหาสารคาม ปีที่ 2 ฉบับที่ 4 กรกฎาคม - ธันวาคม 2560 Management Science Rajabhat Maha Sarakham University Journal Vol. 2 No. 4 : July - December 2017 83 สื่อมวลชนประเทศเมียนมาร์ Journalists in Myanmar สิงห์ สิงห์ขจร 1 Singh Singkhajorn 1 บทคัดย่อ สถานการณ์ของสื่อมวลชนของประเทศเมียนมาร์หลังจากการยกเลิกมาตรการตรวจต้นฉบับของรัฐบาล ทา� ให้มีการออกใบอนุญาตประกอบกิจการใหม่ให้แก่หนังสือพิมพ์เอกชน ทา� ให้หนังสือพิมพ์เอกชนของเมียนมาร์กลับ มาตีพิมพ์วางแผงอีกครั้ง และยังเป็นครั้งแรกในรอบหลายสิบปี ทา� ให้มีการวิพากษ์วิจารณ์รัฐบาลอย่างกว้างขวางใน หน้าหนังสือพิมพ์ ทั้งในเรื่องนโยบาย และการทุจริตคอรัปชั่น และการก่อตั้ง สภาการสื่อมวลชนเมียนมาร์ (Myanmar Press Council : MPC) ในปี 2012 ท�าหน้าที่ก�ากับดูแลสื่อมวลชน ซึ่งในสภานั้น 1 ใน 3 ของสมาชิกมาจากการ แต่งตั้งโดยรัฐบาล และ 2 ใน 3 มาจากนักข่าวที่เป็นตัวแทนของสมาคมต่าง ๆ และการไกล่เกลี่ยประเด็นต่าง ๆ ที่เป็นประเด็นปัญหาการร้องเรียนสื่อมวลชนจ�านวน 70 เรื่อง 2) ความคาดหวังของสื่อมวลชนของประเทศเมียนมาร์ ในการจัดท�าร่างกฎหมายใหม่ของสื่อมวลชนอยู่ในระหว่างการยกร่างกฎหมายสื่อมวลชน (Media Law) ตั้งแต่ปี 2013 จนถึงปัจจุบัน ซึ่งได้มีการน�ากฎหมายที่เกี่ยวข้องกับสื่อมวลชน 6 ฉบับน�ามารวมกฎหมายสื่อมวลชนใหม่ มีการประชุมร่วมกับทั้งตัวแทนของสื่อมวลชน ตัวแทนของรัฐบาล และตัวแทนของสมาชิกสภาแห่งชาติเมียนมาร์ (Union Parliament Myanmar) ประเด็นที่ส�าคัญคือเสรีภาพของสื่อมวลชน และการเข้าถึงข้อมูลข่าวสารของ ราชการ ค�าส�าคัญ : สถานการณ์ สื่อมวลชน ประเทศเมียนมาร์ 1 สาขาวิชาการประชาสัมพันธ์และการสื่อสารองค์การ คณะวิทยาการจัดการ มหาวิทยาลัยราชภัฏบ้านสมเด็จเจ้าพระยา (Email : [email protected]) -

Abstract Cultural Models of Democracy Among Burmese

ABSTRACT CULTURAL MODELS OF DEMOCRACY AMONG BURMESE RESIDENTS IN CHICAGO, ILLINOIS, AND FORT WAYNE, INDIANA John Hillory Hood, M.A. Department of Anthropology Northern Illinois University, 2019 Giovanni Bennardo, Director This thesis examines implicit assumptions about democracy among Burmese residents in Chicago, Illinois and Fort Wayne, Indiana. A major focus of the research is the durability of foundational cultural models – basic, simple, widely-shared modes of thought – that may or may not change over time, measured in this study through length-of-residency. As such, I examined three distinct sample groups: temporary residents, immigrants, and adult offspring of immigrants. This research comprised methods of ethnography, semi-structured interviews, as well as a free- listing memory task. A key point of inquiry is intracultural variation occurring between sample groups. Particular attention was paid to heterogenous discourses from opinion communities, and the inner conflict that such discourses can generate within the mind. Key Words: Burma, Myanmar, Southeast Asia, democracy, cultural model, discourse analysis, cognitive anthropology, intracultural variation, cultural durability, cultural memory, refugee, migration, diaspora, authoritarianism NORTHERN ILLINOIS UNIVERSITY DEKALB, ILLINOIS MAY 2019 CULTURAL MODELS OF DEMOCRACY AMONG BURMESE RESIDENTS IN CHICAGO, ILLINOIS, AND FORT WAYNE, INDIANA BY JOHN HILLORY HOOD ©2019 John Hillory Hood A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE MASTER OF ARTS DEPARTMENT OF ANTHROPOLOGY Thesis Director: Giovanni Bennardo ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This thesis would not have been possible without several people. I would like to acknowledge my thesis director, Giovanni Bennardo, from whom I learned so much about cognitive anthropology and who worked very closely with me even while on sabbatical.