TTSTA Tuesday Week #13 Happy TTSTA Tuesday!

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MISY: Mandalay Campus 2018/2019 Calendar M O Tu W E Th Fr S a Su

MISY: Mandalay Campus 2018/2019 Calendar M W S o Tu e Th Fr a Su Important Dates th th 1 2 3 4 5 10 Aug – 17 Staff induction th 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 25 Aug – School Opening Day Celebration 9.00 am to 12 noon August 27th Aug – Students First Day 2018 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 st (5 days) 31 Aug – Meet the Parents 3.45 pm to 5.30 pm 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 1 2 September 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 4th Sep – Fire Drill @ 9.50 am 2018 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 th st (20 days) 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 17 –21 Anti-Bullying Week 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 st October 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 31 October – Teacher Appreciation Day 2018 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 15th – 19th International Week 22nd- 26th Mid-term holiday / 23rd Pre-full moon of Thadingyut / 24th Full moon of 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 th (18 days) Thadingyut / 25 Post-full moon of Thadingyut 29 30 31 1 2 3 4 1st Nov – Fire Drill @ 11.50 am November 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 2018 12th Parent, Student, Teacher Conferences (Nursery – Year 8) 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 th th 13 -16 Week Without Walls (Years 7- 8) (20 days) 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 21st Pre-full moon of Tasaungmone / 22nd Full moon of Tasaungmone / 26 27 28 29 30 1 2 2nd National Day 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 December th 14 Christmas Shows Written reports released (Nursery – Year 8) / Last Day of 2018 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 Term 1 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 17th School Holidays (10 days) 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 25th Christmas Day 31 31st New Year’s Eve th 1 2 3 4 5 6 4 Independence Day/ 6th Karen New Year Day th st January 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 7 Jan – Students and Teachers 1 Day term 2 2019 -

Shwe U Daung and the Burmese Sherlock Holmes: to Be a Modern Burmese Citizen Living in a Nation‐State, 1889 – 1962

Shwe U Daung and the Burmese Sherlock Holmes: To be a modern Burmese citizen living in a nation‐state, 1889 – 1962 Yuri Takahashi Southeast Asian Studies School of Languages and Cultures Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences The University of Sydney April 2017 A thesis submitted in fulfilment of requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Statement of originality This is to certify that to the best of my knowledge, the content of this thesis is my own work. This thesis has not been submitted for any degree or other purposes. I certify that the intellectual content of this thesis is the product of my own work and that all the assistance received in preparing this thesis and sources has been acknowledged. Yuri Takahashi 2 April 2017 CONTENTS page Acknowledgements i Notes vi Abstract vii Figures ix Introduction 1 Chapter 1 Biography Writing as History and Shwe U Daung 20 Chapter 2 A Family after the Fall of Mandalay: Shwe U Daung’s Childhood and School Life 44 Chapter 3 Education, Occupation and Marriage 67 Chapter ‘San Shar the Detective’ and Burmese Society between 1917 and 1930 88 Chapter 5 ‘San Shar the Detective’ and Burmese Society between 1930 and 1945 114 Chapter 6 ‘San Shar the Detective’ and Burmese Society between 1945 and 1962 140 Conclusion 166 Appendix 1 A biography of Shwe U Daung 172 Appendix 2 Translation of Pyone Cho’s Buddhist songs 175 Bibliography 193 i ACKNOWLEGEMENTS I came across Shwe U Daung’s name quite a long time ago in a class on the history of Burmese literature at Tokyo University of Foreign Studies. -

Pathein University Research Journal 2017, Vol. 7, No. 1

Pathein University Research Journal 2017, Vol. 7, No. 1 2 Pathein University Research Journal 2017, Vol. 7, No. 1 Pathein University Research Journal 2017, Vol. 7, No. 1 3 4 Pathein University Research Journal 2017, Vol. 7, No. 1 စ Pathein University Research Journal 2017, Vol. 7, No. 1 5 6 Pathein University Research Journal 2017, Vol. 7, No. 1 Pathein University Research Journal 2017, Vol. 7, No. 1 7 8 Pathein University Research Journal 2017, Vol. 7, No. 1 Pathein University Research Journal 2017, Vol. 7, No. 1 9 10 Pathein University Research Journal 2017, Vol. 7, No. 1 Spatial Distribution Pattrens of Basic Education Schools in Pathein City Tin Tin Mya1, May Oo Nyo2 Abstract Pathein City is located in Pathein Township, western part of Ayeyarwady Region. The study area is included fifteen wards. This paper emphasizes on the spatial distribution patterns of these schools are analyzed by using appropriate data analysis methods. This study is divided into two types of schools, they are governmental schools and nongovernmental schools. Qualitative and quantitative methods are used to express the spatial distribution patterns of Basic Education Schools in Pathein City. Primary data are obtained from field surveys, informal interview, and open type interview .Secondary data are collected from the offices and departments concerned .Detailed facts are obtained from local authorities and experience persons by open type interview. Key words: spatial distribution patterns, education, schools, primary data ,secondary data Introduction The study area, Pathein City is situated in the Ayeyarwady Region. The study focuses only on the unevenly of spatial distribution patterns of basic education schools in Pathein City . -

A Checklist for Adding Soft Signage to Your Digital Print Business Ebook

A Checklist for Adding Soft Signage to your Digital Print Business Presented by: What you need to know Customers Requirements & Consumables Printing Equipment Finishing Equipment Integration 2 Questions that must be answered? Do you currently manufacture textile goods? If so, what technology/equipment are you using and is it cost effective? Do you currently outsource textiles? If so, how much, what technology/equipment is used, does it make sense to bring in house? 3 Questions that must be answered? Do you already have the customer base or is it a “if I build it they will come” situation? Is your customer buying textiles from someone else? Would they buy from you? Do you fully understand the required equipment and processes involved in manufacturing textiles yourself? Software, printer, direct/transfer, fixation, cutting/finishing/sewing, consumables, fabric, knowledge? 4 Requirements & consumables Control the variables 5 Requirements: Control the variables RIP/Color management software Controlled print room • Water quality • Humidity, temperature, cleanliness • Waste water/ink Equipment settings/logs Media handling equipment & safety 6 Know your environment is controlled! USB data logger • Temperature • Humidity • Dew point • LCD 7 Media handling Transfer paper 105 - 57gsm • 400 lbs roll weight Uniquely Designed • 10.5’ roll width Specifically for the EFI Soft Signage Printer Line • 14” roll diameter Foster 61577 • 990 lbs roll weight • 16.5’ roll width • 19.6” roll diameter 8 Consumables OEM water-based sublimation inks high transfer -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA, IRVINE The

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, IRVINE The Intersection of Economic Development, Land, and Human Rights Law in Political Transitions: The Case of Burma THESIS submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in Social Ecology by Lauren Gruber Thesis Committee: Professor Scott Bollens, Chair Associate Professor Victoria Basolo Professor David Smith 2014 © Lauren Gruber 2014 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF MAPS iv LIST OF TABLES v ACNKOWLEDGEMENTS vi ABSTRACT OF THESIS vii INTRODUCTION 1 CHAPTER 1: Historical Background 1 Late 20th Century and Early 21st Century Political Transition 3 Scope 12 CHAPTER 2: Research Question 13 CHAPTER 3: Methods 13 Primary Sources 14 March 2013 International Justice Clinic Trip to Burma 14 Civil Society 17 Lawyers 17 Academics and Politicians 18 Foreign Non-Governmental Organizations 19 Transitional Justice 21 Basic Needs 22 Themes 23 Other Primary Sources 23 Secondary Sources 24 Limitations 24 CHAPTER 4: Literature Review Political Transitions 27 Land and Property Law and Policy 31 Burmese Legal Framework 35 The 2008 Constitution 35 Domestic Law 36 International Law 38 Private Property Rights 40 Foreign Investment: Sino-Burmese Relations 43 CHAPTER 5: Case Studies: The Letpadaung Copper Mine and the Myitsone Dam -- Balancing Economic Development with Human ii Rights and Property and Land Laws 47 November 29, 2012: The Letpadaung Copper Mine State Violence 47 The Myitsone Dam 53 CHAPTER 6: Legal Analysis of Land Rights in Burma 57 Land Rights Provided by the Constitution 57 -

Theocracy Metin M. Coşgel Thomas J. Miceli

Theocracy Metin M. Coşgel University of Connecticut Thomas J. Miceli University of Connecticut Working Paper 2013-29 November 2013 365 Fairfield Way, Unit 1063 Storrs, CT 06269-1063 Phone: (860) 486-3022 Fax: (860) 486-4463 http://www.econ.uconn.edu/ This working paper is indexed on RePEc, http://repec.org THEOCRACY by Metin Coşgel* and Thomas J. Miceli** Abstract: Throughout history, religious and political authorities have had a mysterious attraction to each other. Rulers have established state religions and adopted laws with religious origins, sometimes even claiming to have divine powers. We propose a political economy approach to theocracy, centered on the legitimizing relationship between religious and political authorities. Making standard assumptions about the motivations of these authorities, we identify the factors favoring the emergence of theocracy, such as the organization of the religion market, monotheism vs. polytheism, and strength of the ruler. We use two sets of data to test the implications of the model. We first use a unique data set that includes information on over three hundred polities that have been observed throughout history. We also use recently available cross-country data on the relationship between religious and political authorities to examine these issues in current societies. The results provide strong empirical support for our arguments about why in some states religious and political authorities have maintained independence, while in others they have integrated into a single entity. JEL codes: H10, -

Thai-Burmese Warfare During the Sixteenth Century and the Growth of the First Toungoo Empire1

Thai-Burmese warfare during the sixteenth century 69 THAI-BURMESE WARFARE DURING THE SIXTEENTH CENTURY AND THE GROWTH OF THE FIRST TOUNGOO EMPIRE1 Pamaree Surakiat Abstract A new historical interpretation of the pre-modern relations between Thailand and Burma is proposed here by analyzing these relations within the wider historical context of the formation of mainland Southeast Asian states. The focus is on how Thai- Burmese warfare during the sixteenth century was connected to the growth and development of the first Toungoo empire. An attempt is made to answer the questions: how and why sixteenth century Thai-Burmese warfare is distinguished from previous warfare, and which fundamental factors and conditions made possible the invasion of Ayutthaya by the first Toungoo empire. Introduction As neighbouring countries, Thailand and Burma not only share a long border but also have a profoundly interrelated history. During the first Toungoo empire in the mid-sixteenth century and during the early Konbaung empire from the mid-eighteenth to early nineteenth centuries, the two major kingdoms of mainland Southeast Asia waged wars against each other numerous times. This warfare was very important to the growth and development of both kingdoms and to other mainland Southeast Asian polities as well. 1 This article is a revision of the presentations in the 18th IAHA Conference, Academia Sinica (December 2004, Taipei) and The Golden Jubilee International Conference (January 2005, Yangon). A great debt of gratitude is owed to Dr. Sunait Chutintaranond, Professor John Okell, Sarah Rooney, Dr. Michael W. Charney, Saya U Myint Thein, Dr. Dhiravat na Pombejra and Professor Michael Smithies. -

Bailey Aw20 Western

Western Handbook 2020 Promoting American craftsmanship and Proud Member of ingenuity. This product complies with American Made Matters® American Made Matters® standards for Made in America. Bailey Showroom WESTERN HANDBOOK 411 Fifth Avenue, 2nd Floor, New York, NY 10016 2020 Global Customer Service and Distribution Center ® ® 50 Denver Road, Denver, PA 18517 Bailey Renegade Tel: 800-927-4539 Fax: 717-336-0148 Toll Free Fax: 888-428-7329 Straw 4 Straw 36 20x 4 Felt 37 15x 12 ® 10x 17 Wind River 7x 20 Straw 39 4x 21 Felt 42 Gunmetal Spur Pin Bangora 22 ® Felt 24 Eddy Bros. 100x 24 Straw 46 20x 25 Felt 47 10x 26 Bailey® Hat Box Mini Metal Spur Pin Kids 50 7x, 5x, 27 4x, 3x 28 Hat Size Converstion Chart 2x 30 Swatches 51 Size USA Metric Inches Frontier 34 XS 65/8 53 cm 20 3/4 Kids 35 6 3/4 54 cm 21 1/8 S 6 7/8 55 cm 21 1/2 7 56 cm 21 7/8 M 7 1/8 57 cm 22 1/4 7 1/4 58 cm 22 5/8 L 7 3/8 59 cm 23 7 1/2 60 cm 23 1/2 XL 7 5/8 61 cm 23 7/8 7 3/4 62 cm 24 1/4 7/8 5/8 XXL 7 63 cm 24 Bailey®, Renegade®, Eddy Bros®, Wind River®, LiteStraw®, and LiteFelt® are registered trademarks of the Bollman Hat Company. 3 20x New New 20x S2020A Deuce 20x S2020B Banco 5 3/4” Dallas Crown Brim: 4 1/2” 4” Rodeo Crown Brim: 4 1/2” Natural Sizes: 6 5/8” – 7 5/8” Natural Sizes: 6 5/8” – 7 5/8” 4 20x 20x S1920A Berserk 20x S1920B Taos 4” Rodeo Crown Brim: 4 1/2” 4” Rodeo Crown Brim: 4 1/2” Natural Sizes: 6 3/4” – 7 5/8” Beige Sizes: 6 5/8” – 7 5/8” 5 20x 6 Made in the USA of US and imported components. -

Burma Road to Poverty: a Socio-Political Analysis

THE BURMA ROAD TO POVERTY: A SOCIO-POLITICAL ANALYSIS' MYA MAUNG The recent political upheavals and emergence of what I term the "killing field" in the Socialist Republic of Burma under the military dictatorship of Ne Win and his successors received feverish international attention for the brief period of July through September 1988. Most accounts of these events tended to be journalistic and failed to explain their fundamental roots. This article analyzes and explains these phenomena in terms of two basic perspec- tives: a historical analysis of how the states of political and economic devel- opment are closely interrelated, and a socio-political analysis of the impact of the Burmese Way to Socialism 2, adopted and enforced by the military regime, on the structure and functions of Burmese society. Two main hypotheses of this study are: (1) a simple transfer of ownership of resources from the private to the public sector in the name of equity and justice for all by the military autarchy does not and cannot create efficiency or elevate technology to achieve the utopian dream of economic autarky and (2) the Burmese Way to Socialism, as a policy of social change, has not produced significant and fundamental changes in the social structure, culture, and personality of traditional Burmese society to bring about modernization. In fact, the first hypothesis can be confirmed in light of the vicious circle of direct controls-evasions-controls whereby military mismanagement transformed Burma from "the Rice Bowl of Asia," into the present "Rice Hole of Asia." 3 The second hypothesis is more complex and difficult to verify, yet enough evidence suggests that the tradi- tional authoritarian personalities of the military elite and their actions have reinforced traditional barriers to economic growth. -

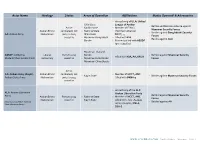

ACLED – Myanmar Conflict Update – Table 1

Actor Name Ideology Status Areas of Operation Affiliations Modus Operandi & Adversaries - Armed wing of ULA: United - Chin State League of Arakan - Battles and Remote violence against Active - Kachin State - Member of FPNCC Myanmar Security Forces Arakan Ethnic combatant; not - Rakhine State (Northern Alliance) - Battles against Bangladeshi Security AA: Arakan Army Nationalism party to 2015 - Shan State - NCCT, , , Forces ceasefire - Myanmar-Bangladesh - Allied with KIA - Battles against ALA Border - Formerly allied with ABSDF (pre-ceasefire) - Myanmar-Thailand ABSDF: All Burma Liberal Party to 2015 Border - Battled against Myanmar Security - Allied with KIA, AA, KNLA Students’ Democratic Front democracy ceasefire - Myanmar-India Border Forces - Myanmar-China Border Active AA: Arakan Army (Kayin): Arakan Ethnic combatant; not - Member of NCCT, ANC - Kayin State - Battles against Myanmar Security Forces Arakan State Army Nationalism party to 2015 - Allied with DKBA-5 ceasefire - Armed wing of the ALP: ALA: Arakan Liberation Arakan Liberation Party - Battled against Myanmar Security Army Arakan Ethnic Party to 2015 - Rakhine State - Member of NCCT, ANC Forces Nationalism ceasefire - Kayin State - Allied with AA: Arakan (Also known as RSLP: Rakhine - Battled against AA State Liberation Party) Army (Kayin), KNLA, SSA-S WWW.ACLEDDATA.COM | Conflict Update – Myanmar – Table 1 Rohingya Ethnic Active ARSA: Arakan Rohingya - Rakhine State Nationalism; combatant; not Salvation Army - Myanmar-Bangladesh UNKNOWN - Battles against Myanmar Security -

Research Impact of Pāli on the Development of Myanmar Literature

Journal homepage: http://twasp.info/journal/home Research Impact of Pāli on the Development of Myanmar Literature Dr- Tin Tin New1*, Yee Mon Phay2, Dr- Minn Thant3 1Professor, Department of Oriental Studies, Mandalay University, Mandalay, Myanmar 2PhD Candidate, School of Liberal Arts, Department of Global Studies, Shanghai University, Shanghai, China 3Lecturer, Department of Oriental Studies, Mandalay University, Myanmar *Corresponding author Accepted:19 August, 2019 ;Online: 25 August, 2019 DOI : https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3377041 Abstract Buddhism introduced Myanmar since the first century AD and there prospered in about 4th to 5th century AD in Śriksetra (Hmawza, Pyay), Suvannabhūmi (Thaton), Rakhine and Bagan. Since that time, people of Myanmar made their effort to develop and prosper Buddhism having studied Pāli, the language of Theravāda Buddhism. In Bagan period, they attempted to create Burmese scripts and writing system imitating to Pāli. From that time Myanmar Literature gradually had been developed up to present. In this paper it is shed a light about influence of Pāli on Myanmar Literature. Keywords Burmese literature, Ancient literature. Impact of Pāli on the Development of Myanmar Literature Literary and archaeological sources as founded in Śriksetra (Hmawza, Pyay), Suvannabhūmi (Thaton), Rakhine and Bagan proved that Buddhism introduced Myanmar since the first century AD and there prospered in about 4th to 5th century AD. Pyu people recorded Pāli extracts in Pyu scripts, Mon also recorded Pāli in their own scripts and Myanmar recorded Pāli in Myanmar script. In this way, people of Myanmar made their effort to develop and prosper Buddhism having studied Pāli, the language of Theravāda Buddhism. -

Kayah State: Myanmar’S Hidden Gem Discover the Unknown Myanmar at ITB 2016

MEDIA ADVISORY: 07.03.2016 Kayah State: Myanmar’s hidden gem Discover the unknown Myanmar at ITB 2016 (Yangon/Berlin) – Myanmar Tourism Marketing (MTM) in partnership with the International Trade Centre (ITC) and the United Nations World Tourism Organization (UNWTO) will on 9 March 2015 present Kayah State as Myanmar’s latest tourist destination. The presentation will take place on during the Internationale Tourismus Börse (ITB) 2016 2016, taking place in Berlin. New cultural tourism tours and experiences will be presented, and the media and other participants are invited to join any of these events and meet with representatives from ITC and Kayah State. More than 5 million people visited Myanmar in 2015, but tourism has so far been concentrated on a few destinations, including the bustling capital of Yangon, the colonial Mandalay, the temples of Bagan and Inle Lake. However, recent political changes in the country have led to a surge interest from visitors who want to discover Myanmar’s many hidden gems. One such gem is Kayah State, situated in the country’s east. Closed for over half a century and recently opened to visitors, Kayah is one of South-East Asia´s last frontiers for inspiring, authentic travel. With pristine nature, ethnic diversity and a location close to Inle Lake and the Thai border, Kayah holds great potential for cultural tourism in the small local villages and offers a privileged insight into traditional ways of life. As part of the ‘Myanmar Inclusive Tourism Focusing on Kayah State’ project, launched in 2014 and funded by the Netherlands Trust Fund, ITC has worked with the Government of Myanmar to develop suitable cultural and ecotourism products, preparing local communities for the arrival of international visitors.