Translating Rule of Law to Myanmar

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Journal of Urban History

Journal of Urban History http://juh.sagepub.com/ Urban Forms and Civic Space in Nineteenth- to Early Twentieth-Century Bangkok and Rangoon Elizabeth Howard Moore and Navanath Osiri Journal of Urban History 2014 40: 158 originally published online 27 September 2013 DOI: 10.1177/0096144213504381 The online version of this article can be found at: http://juh.sagepub.com/content/40/1/158 Published by: http://www.sagepublications.com On behalf of: Urban History Association Additional services and information for Journal of Urban History can be found at: Email Alerts: http://juh.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts Subscriptions: http://juh.sagepub.com/subscriptions Reprints: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav Permissions: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav >> Version of Record - Nov 26, 2013 OnlineFirst Version of Record - Sep 27, 2013 What is This? Downloaded from juh.sagepub.com at SOAS London on December 1, 2013 JUH40110.1177/0096144213504381Journal of Urban HistoryHoward-Moore and Osiri 504381research-article2013 Article Journal of Urban History 2014, Vol 40(1) 158 –177 Urban Forms and Civic Space in © 2013 SAGE Publications Reprints and permissions: Nineteenth- to Early Twentieth- sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav DOI: 10.1177/0096144213504381 Century Bangkok and Rangoon juh.sagepub.com Elizabeth Howard Moore1 and Navanath Osiri2 Abstract Buddhist spaces in Bangkok and Rangoon both had long common traditions prior to nineteenth- and early twentieth-century colonial incursions. Top–down central city planning with European designs transformed both cities. While Siamese kings personally initiated civic change that began to widen economic and social interaction of different classes, British models segregated European, Burmese, Indian, and Chinese populations to exacerbate social differences. -

Materiality and Construction of a Church in Myanmar

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Theses from the M. Arch. Program Architecture, College of Spring 5-3-2021 Materiality and Construction of a Church in Myanmar Sunkist Judson University of Nebraska-Lincoln Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/marchthesis Part of the Architecture Commons Judson, Sunkist, "Materiality and Construction of a Church in Myanmar" (2021). Theses from the M. Arch. Program. 31. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/marchthesis/31 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Architecture, College of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses from the M. Arch. Program by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. University of Nebraska-Lincoln Materiality and Construction of a Church in Myanmar By: Sunkist Judson A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FUL- FILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE Master of Architecture APPROVED, THESIS COMMITTEE: Sign and Date Dr. Sharon Kuska Materiality and Construction of a Church in Myanmar Sunkist Judson April 29th, 2021 ARCH 544 Thesis Spring 2021 01 02 Abstract This is my investigation related to Theinla village church. This is an investigation of architectural impacts on a protestant religious house of worship experience through a cultural case study. Churches were built and design based on worship culture and traditions. Churches have evolved for over two thousand years due to innovation and technology and imitating previous architecture styles. The way people worship in protestant religion is a little different in every culture. I would like to find out if there is any overlap in Baptist churches in different cultures. -

University of Mandalay Mandalay, Myanmar March 2007 Tint Lwin

University of Mandalay ART AND ARCHITECTURE IN PAKHAN GYI DURING THE MONARCHICAL DAYS Tint Lwin Mandalay, Myanmar March 2007 ART AND ARCHITECTURE IN PAKHAN GYI DURING THE MONARCHICAL DAYS University of Mandalay ART AND ARCHITECTURE IN PAKHAN GYI DURING THE MONARCHICAL DAYS A Dissertation submitted to University of Mandalay in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in History Department of History Tint Lwin 4 Ph.D/Hist.-3 Mandalay, Myanmar March 2007 University of Mandalay ART AND ARCHITECTURE IN PAKHAN GYI DURING THE MONARCHICAL DAYS By Tint Lwin, B.A(Hist:), M.A. 4 Ph.D./Hist.-3 (2006-07) This Dissertation is submitted to the Board of Examiners In History, University of Mandalay in Candidature For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Approved External Examiner, Referee Supervisor Member Member Co-Supervisor Chairperson Abstract In writing this dissertation on the "Art and Architecture in Pakhangyi during the monarchical days", every conceivable aspect has been covered, and the dissertation is divided into four chapters. In writing the First Chapter, the artifacts and implements of Neolithic age period, the religious edifices and wall paintings are mainly used as evidences to show the development of Pakhangyi region as one of the main centres of Myanmar civilization other than Bagan and other places of cultural interest. The First Chapter asserts the historical and cultural legitimacy of the Pakhangyi region by presenting its visible facets of successive periods starting from the stone age: stone implements, how the very term Pakhangyi emerge, the oldest villages, the massive city wall, how the city was rebuilt five times, the quality of bricks used and the pattern of brick bonding, water supply system, agriculture and the region’s inhabitants. -

Burma Watching: a Retrospective

Griffith Asia Institute Regional Outlook Burma Watching: A Retrospective Andrew Selth About the Griffith Asia Institute The Griffith Asia Institute produces innovative, interdisciplinary research on key developments in the politics, economics, societies and cultures of Asia and the South Pacific. By promoting knowledge of Australia’s changing region and its importance to our future, the Griffith Asia Institute seeks to inform and foster academic scholarship, public awareness and considered and responsive policy making. The Institute’s work builds on a 41 year Griffith University tradition of providing cutting- edge research on issues of contemporary significance in the region. Griffith was the first University in the country to offer Asian Studies to undergraduate students and remains a pioneer in this field. This strong history means that today’s Institute can draw on the expertise of some 50 Asia–Pacific focused academics from many disciplines across the university. The Griffith Asia Institute’s ‘Regional Outlook’ papers publish the institute’s cutting edge, policy-relevant research on Australia and its regional environment. They are intended as working papers only. The texts of published papers and the titles of upcoming publications can be found on the Institute’s website: www.griffith.edu.au/asiainstitute ‘Burma Watching: A Retrospective’, Regional Outlook Paper No. 39, 2012. About the Author Andrew Selth Andrew Selth is an Adjunct Research Fellow at the Griffith Asia Institute. He has been studying international security issues and Asian affairs for 40 years, as a diplomat, strategic intelligence analyst and research scholar. He has published four books and more than 50 other peer-reviewed works, most of them about Burma and related subjects. -

The Journal of the Walters Art Museum

THE JOURNAL OF THE WALTERS ART MUSEUM VOL. 73, 2018 THE JOURNAL OF THE WALTERS ART MUSEUM VOL. 73, 2018 EDITORIAL BOARD FORM OF MANUSCRIPT Eleanor Hughes, Executive Editor All manuscripts must be typed and double-spaced (including quotations and Charles Dibble, Associate Editor endnotes). Contributors are encouraged to send manuscripts electronically; Amanda Kodeck please check with the editor/manager of curatorial publications as to compat- Amy Landau ibility of systems and fonts if you are using non-Western characters. Include on Julie Lauffenburger a separate sheet your name, home and business addresses, telephone, and email. All manuscripts should include a brief abstract (not to exceed 100 words). Manuscripts should also include a list of captions for all illustrations and a separate list of photo credits. VOLUME EDITOR Amy Landau FORM OF CITATION Monographs: Initial(s) and last name of author, followed by comma; italicized or DESIGNER underscored title of monograph; title of series (if needed, not italicized); volume Jennifer Corr Paulson numbers in arabic numerals (omitting “vol.”); place and date of publication enclosed in parentheses, followed by comma; page numbers (inclusive, not f. or ff.), without p. or pp. © 2018 Trustees of the Walters Art Gallery, 600 North Charles Street, Baltimore, L. H. Corcoran, Portrait Mummies from Roman Egypt (I–IV Centuries), Maryland 21201 Studies in Ancient Oriental Civilization 56 (Chicago, 1995), 97–99. Periodicals: Initial(s) and last name of author, followed by comma; title in All Rights Reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced without the written double quotation marks, followed by comma, full title of periodical italicized permission of the Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, Maryland. -

Refugees from Burma Acknowledgments

Culture Profile No. 21 June 2007 Their Backgrounds and Refugee Experiences Writers: Sandy Barron, John Okell, Saw Myat Yin, Kenneth VanBik, Arthur Swain, Emma Larkin, Anna J. Allott, and Kirsten Ewers RefugeesEditors: Donald A. Ranard and Sandy Barron From Burma Published by the Center for Applied Linguistics Cultural Orientation Resource Center Center for Applied Linguistics 4646 40th Street, NW Washington, DC 20016-1859 Tel. (202) 362-0700 Fax (202) 363-7204 http://www.culturalorientation.net http://www.cal.org The contents of this profile were developed with funding from the Bureau of Population, Refugees, and Migration, United States Department of State, but do not necessarily rep- resent the policy of that agency and the reader should not assume endorsement by the federal government. This profile was published by the Center for Applied Linguistics (CAL), but the opinions expressed herein do not necessarily reflect positions or policies of CAL. Production supervision: Sanja Bebic Editing: Donald A. Ranard Copyediting: Jeannie Rennie Cover: Burmese Pagoda. Oil painting. Private collection, Bangkok. Design, illustration, production: SAGARTdesign, 2007 ©2007 by the Center for Applied Linguistics The U.S. Department of State reserves a royalty-free, nonexclusive, and irrevocable right to reproduce, publish, or otherwise use, and to authorize others to use, the work for Government purposes. All other rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, in any form or by any means, without permission in writing from the publisher. All inquiries should be addressed to the Cultural Orientation Resource Center, Center for Applied Linguistics, 4646 40th Street, N.W., Washington, D.C. 20016. -

Myanmar (Burma): a Reading Guide Andrew Selth

Griffith Asia Institute Research Paper Myanmar (Burma): A reading guide Andrew Selth i About the Griffith Asia Institute The Griffith Asia Institute (GAI) is an internationally recognised research centre in the Griffith Business School. We reflect Griffith University’s longstanding commitment and future aspirations for the study of and engagement with nations of Asia and the Pacific. At GAI, our vision is to be the informed voice leading Australia’s strategic engagement in the Asia Pacific— cultivating the knowledge, capabilities and connections that will inform and enrich Australia’s Asia-Pacific future. We do this by: i) conducting and supporting excellent and relevant research on the politics, security, economies and development of the Asia-Pacific region; ii) facilitating high level dialogues and partnerships for policy impact in the region; iii) leading and informing public debate on Australia’s place in the Asia Pacific; and iv) shaping the next generation of Asia-Pacific leaders through positive learning experiences in the region. The Griffith Asia Institute’s ‘Research Papers’ publish the institute’s policy-relevant research on Australia and its regional environment. The texts of published papers and the titles of upcoming publications can be found on the Institute’s website: www.griffith.edu.au/asia-institute ‘Myanmar (Burma): A reading guide’ February 2021 ii About the Author Andrew Selth Andrew Selth is an Adjunct Professor at the Griffith Asia Institute, Griffith University. He has been studying international security issues and Asian affairs for 45 years, as a diplomat, strategic intelligence analyst and research scholar. Between 1974 and 1986 he was assigned to the Australian missions in Rangoon, Seoul and Wellington, and later held senior positions in both the Defence Intelligence Organisation and Office of National Assessments. -

Title Integration of Traditional Architectural Identities With

Integration of Traditional Architectural Identities with Title Contemporary Myanmar Houses in Central Myanmar( Dissertation_全文 ) Author(s) Nandar, Linn Citation 京都大学 Issue Date 2018-03-26 URL https://doi.org/10.14989/doctor.k21078 Right Type Thesis or Dissertation Textversion ETD Kyoto University Integration of Traditional Architectural Identities with Contemporary Myanmar Houses in Central Myanmar Nandar Linn 2018 Integration of Traditional Architectural Identities with Contemporary Myanmar Houses in Central Myanmar A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Engineering Nandar Linn 2018 KYOTO UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL OF ENGINEERING DEPARTMENT OF CIVIL AND EARTH RESOURCES ENGINEERING i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The author would like to express her sincere and deepest gratitude to Professor Masashi Kawasaki from Urban and Landscape Design Laboratory, Department of Civil and Earth Resources Engineering, Kyoto University for accepting her as his student and giving her precious guidance, criticism and generous support for the accomplishment of this thesis. She is deeply indebted to the continuous help, understanding and guidance from Associate Professor Keita Yamaguchi from Urban and Landscape Design Laboratory. Sincere thanks and appreciation are also extended to Professor Yoshiaki Kubota for his valuable suggestions and support before and even after he has been appointed in Toyama University. She owes a debt of gratitude to Professor Nobuhiro Uno from Department of Civil and Earth Resources Engineering who generously shared his knowledge and suggestions throughout the reviewing process of her dissertation. She is greatly indebted to all the professors in Department of Civil and Earth Resources Engineering and the lecturers who have contributed in Kyoto University Global COE Program on Human Security Engineering for all of their valuable lectures. -

The Significance of the Visual Culture of Three Foreign Temples at Bodhgaya (India) a Sri Lankan, Burmese and Thai Temple

15-07-2016 The significance of the visual culture of three foreign temples at Bodhgaya (India) A Sri Lankan, Burmese and Thai Temple Student: Shita Bakker, Student No: S0951730 Master Asian Studies, History, Arts and Culture of Asia Supervisor: Prof. Dr. Marijke J. Klokke Word count: 15.298 Content Chapter 1. Introduction 1.1 Brief background information and description of three foreign temples 1.2 Theravada Buddhism 1.3 Previous literature on the subject 1.4 Relevance of paper and research questions 1.5 Methodology and approach 1.6 Short note on terminology Chapter 2. Bodhgaya, from a lieu de mémoire into a global village 2.1 History and memory 2.2 The idea of conscious remembering 2.3 Conclusion Chapter 3. The visual elements of the foreign temples expressing Bodhgaya as a lieu de mémoire 3.1 The Sri Lankan Temple and Bodhgaya as a lieu de mémoire 3.2 Sri Lanka and its relation to Bodhgaya 3.3 The Burmese Temple and Bodhgaya as a lieu de mémoire 3.4 Burma and its relation to Bodhgaya 3.5 The Thai Temple and Bodhgaya as a lieu de mémoire 3.6 Thailand and its relation to Bodhgaya 3.7 Conclusion Chapter 4. The temples and the visual expression of their domestic cultures 4.1 The Sri Lankan Temple and its visual culture ` 4.2 The Burmese Temple and its visual culture 4.3 The Thai Temple and its visual culture 4.4 Conclusion Chapter 5. Conclusion 2 Chapter 1. Introduction Bodhgaya is situated in the state of Bihar in India and is known as the place where the Buddha became awakened while sitting under a Bodhi tree, which is marked by the diamond seat (Sanskrit: vajrasana). -

Reflections on the Red Sea Style: Beyond the Surface of Coastal Architecture

Binghamton University The Open Repository @ Binghamton (The ORB) Art History Faculty Scholarship Art History 2012 Reflections on the Red Sea Style: Beyond the Surface of Coastal Architecture Nancy Um Binghamton University--SUNY, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://orb.binghamton.edu/art_hist_fac Part of the Architectural History and Criticism Commons, and the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Recommended Citation Nancy Um, “Reflections on the Red Sea Style: Beyond the Surface of Coastal Architecture,” Northeast African Studies 12:1 (2012): 243-271. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Art History at The Open Repository @ Binghamton (The ORB). It has been accepted for inclusion in Art History Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of The Open Repository @ Binghamton (The ORB). For more information, please contact [email protected]. Reflections on the Red Sea Style: Beyond the Surface of Coastal Architecture Nancy Um, Binghamton University, Binghamton, New York, USA ABSTRACT In 1953, a British architect named Derek H. Matthews introduced the idea of “The Red Sea Style” in print, in a modest article with that title. Although brief and focused on a single site, this article proposed that the architecture around the rim of the Red Sea could be conceived of as a coherent and unified building category. Since then, those who have written about Red Sea port cities have generally ac- cepted Matthews’s suggestion of a shared architectural culture. Indeed, the houses of the region’s major ports, such as Suakin in modern-day Sudan, Massawa in Eritrea, Jidda and Yanbuᶜ al-Baḥr in Saudi Arabia, and Mocha, al-Ḥudayda, and al-Luḥayya in Yemen, share a number of visual similarities that support this cross- regional designation. -

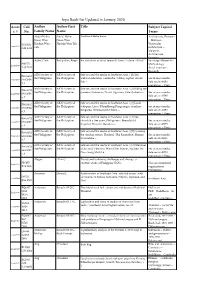

Inya Book-List Updated in January 2020

Inya Book-list Updated in January 2020 Acces Call Author Author First Title Subject Topical s. # No. Family Name Name Terms Abdul Halim Abdul Halim Traditional Malay house Architecture, Domestic Nasir, Wan Nasir, Wan -- Malaysia. NA7436 . Hashim Wan Hashim Wan Teh. Vernacular Inya-0335 A24 1996 Teh. architecture -- Malaysia. Architecture, Domestic. Adler; Clark Emily Stier; Roger An invitation to social research : how it's done / 4th ed Sociology--Research-- HM571 . Methodology. Inya-0399 A35 2011 Social sciences-- Research-- AIDS Society of AIDS Society of Safe sex and the media in Southeast Asia. / [1] Sex Methodology. P96.S452 the Philippines. the Philippines. without substance, Cambodia / Chhay Sophal, Steven Sex in mass media. Inya-0283 S68 2004 Pak -- Safe sex in AIDS v.1 prevention -- Press AIDS Society of AIDS Society of Safe sex and the media in Southeast Asia. / [2] Riding the coverage -- Southeast P96.S452 the Philippines. the Philippines. paradox, Indonesia / Nurul Agustina, Irwan Julianto -- Asia.Sex in mass media. Inya-0410 S68 2004 SexualSafe sex health in AIDS -- Press v.2 coverageprevention -- --Southeast Press AIDS Society of AIDS Society of Safe sex and the media in Southeast Asia. / [3] Loud Asia.coverage -- Southeast P96.S452 the Philippines. the Philippines. whispers, Laos / Khamkhong Kongvongsa, Somkiao Asia.Sex in mass media. Inya-0411 S68 2004 Kingsada, Phonesavanh Thikeo -- SexualSafe sex health in AIDS -- Press v.3 coverageprevention -- --Southeast Press AIDS Society of AIDS Society of Safe sex and the media in Southeast Asia. / [4] Sex, Asia.coverage -- Southeast P96.S452 the Philippines. the Philippines. church & a free press, Philippines / Reynaldo H. -

Study on Form and Space of Shwe Ye Taik Monastery in Mawlamyine City

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL FOR INNOVATIVE RESEARCH IN MULTIDISCIPLINARY FIELD ISSN – 2455-0620 Volume - 3, Issue - 1, Jan - 2017 STUDY ON FORM AND SPACE OF SHWE YE TAIK MONASTERY IN MAWLAMYINE CITY, MYANMAR SAN SAN MYINT1 , Dr.MG HLAING2 , Dr.YIN MIN PAIK3 1Ph.D Candidate, Department of Architecture, Yangon Technological University, Yangon, Myanmar 2Professor, Department of Architecture, Yangon Technological University, Yangon, Myanmar 3Associate Professor, Department of Architecture, Yangon Technological University, Yangon, Myanmar Email – [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] Abstract: Every Country has its’ own Architectural style. Myanmar also has its’ unique Architecture which is difference from other countries’ Architecture. Religious buildings have much Architectural features than any other building types. Among them, Monasteries possess most of the Myanmar Architectural features and creation.In this paper, the functions, spatial composition and form composition of Shwe Ye Taik Monastery is studied. Firstly, the development of the Monasteries in Myanmar is studied. It will include the coming of monasteries in buddhism, the evolution of monasteries in Myanmar. And then, the general information of Shwe Ye Taik Monastery is studied. Finally, the author would like to figure out what kinds of function are used in Shwe Ye Taik Monastery. And then, the author wishes to point out the creation of spatial composition and form composition ofthis monastery. This paper aims to realize the real unique architecture of Myanmar Monasteries. The heritage Monasteries can be conserved and recorded. Architectural creation can be used in future Monasteries. Key Words: Shwe Ye Taik Monastery, Function, Spatial Composition, Form Composition. 1. INTRODUCTION: Myanmar is a country which has great history, culture and architecture.