Introduction Introduction Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Letter from the Dean

C News fromIR the University of ChicagoC DivinityA School STAGE DIRECTIONS: SCENE TWO. MY ROOM 101. (Enter Miriam.) A woman in her early 60s strides to the front of a large lecture hall, dark wood paneling. She waits for the class to quiet down, for the school bell to fade away. MIRIAM: (holding the book up again) This is the most powerful, and the most dangerous…text… inA merican culture today. And so we’d better try to understand what’s in it, don’t you think?* Earlier this month I stood backstage at Joe’s their experiences, beliefs and values, she Pub, a venue for public performance on the goes on to share much more of her own on east side of New York City, with playwrights day one (including a recurrent childhood Lisa Peterson and Denis O’Hare, actors memory) than many teachers (myself F. Murray Abraham and Micah Stock, and Letter included) would be comfortable with. But in popular author Bruce Feiler, waiting to go the performance I did have fun with Miriam; out front and do a dramatic reading of four I camped it up a bit with “first day of the scenes from a play in progress, The Good from the semester” bravura, playing to a crowd of Book. This play, commissioned by Court ersatz students who (while eating arugula Theatre from the authors of the highly and drinking Brooklyn lager) might mistake acclaimed An Iliad, will have its world premier Dean the professor for the subject matter (and at Court on March 19, 2015. -

Philip Melanchthon and the Historical Luther by Ralph Keen 7 2 Philip Melanchthon’S History of the Life and Acts of Dr Martin Luther Translated by Thomas D

VANDIVER.cvr 29/9/03 11:44 am Page 1 HIS VOLUME brings By placing accurate new translations of these two ‘lives of Luther’ side by side, Vandiver together two important Luther’s T and her colleagues have allowed two very contemporary accounts of different perceptions of the significance of via free access the life of Martin Luther in a Luther to compete head to head. The result is as entertaining as it is informative, and a Luther’s confrontation that had been postponed for more than four powerful reminder of the need to ensure that secondary works about the Reformation are hundred and fifty years. The first never displaced by the primary sources. of these accounts was written imes iterary upplement after Luther’s death, when it was rumoured that demons had seized lives the Reformer on his deathbed and dragged him off to Hell. In response to these rumours, Luther’s friend and colleague, Downloaded from manchesterhive.com at 09/25/2021 06:33:04PM Philip Melanchthon wrote and Elizabeth Vandiver, Ralph Keen, and Thomas D. Frazel - 9781526120649 published a brief encomium of the Reformer in . A completely new translation of this text appears in this book. It was in response to Melanchthon’s work that Johannes Cochlaeus completed and published his own monumental life of Luther in , which is translated and made available in English for the first time in this volume. After witnessing Luther’s declaration before Charles V at the Diet of Worms, Cochlaeus had sought out Luther and debated with him. However, the confrontation left him convinced that Luther was an impious and —Bust of Luther, Lutherhaus, Wittenberg. -

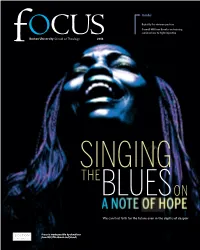

The One Who Even Did It, but It’S Methodist Bishop-In-Residence

182462 BU 182462 Cover~P.pdf 1 5_17_2018 Nonprofit Inside: US Postage PAID Equality for women pastors Boston MA Cornell William Brooks on training 745 Commonwealth Avenue Permit No. 1839 seminarians to fight injustice Boston, Massachusetts 02215 2018 At STH, I was surrounded by professors and supervisors who were passionate about preparing me for the journey that followed, and colleagues who were exploring how God was involved in their lives and in the world. The impact of my theological education on my personal and professional SINGING development has been long-standing, for which I am very grateful. THE Frank J. Richardson, Jr. (’77,’82) Richardson has included a gift to STH in his estate plans. BLUESON Education is a gift. Pass it on. We can find faith for the future even in the depths of despair MAKE YOUR IMPACT THROUGH A PLANNED GIFT Contact us today at [email protected] or 800-645-2347 focus is made possible by donations Dotty Raynor from BU STH alumni and friends 182462 BU 182462 Cover~P.pdf 2 5_17_2018 182462 BU 182462 Text~P.pdf 3 5_17_2018 TABLEof Boston University CONTENTS School of Theology 2018 DEAN’S MESSAGE 2 JOURNAL: LEADERSHIP IN A TIME OF TURMOIL Dean MARY ELIZABETH MOORE Director of Development FEATURES Singing the Blues on a Note of Hope 20 Martin Luther, Rebel with a Cause 36 RAY JOYCE (Questrom’91) Holding on when we’re harassed by hell A profile of the reformer who upended the Alumni Relations Officer By Julian Armand Cook (’16) Church in his quest to heal it Tiny Homes for Big Dreams 10 JACLYN K. -

American Society of Church History 2017 Council Reports Table Of

American Society of Church History 2017 Council Reports Table of Contents President’s Report Executive Secretary’s Report Nominating Committee’s Report Church History Editor’s Report Membership Committee Report Research and Prize Committee Report Program Committee Report GS / IS Committee Report 0 President’s Report The year 2017 has been a season of transition and growth for ASCH in terms of: 1) Staffing, 2) Conferences; 3) Governance; 4) Diversity. 1) Staffing ASCH’s Executive Secretary Keith Francis submitted his resignation, effective December 31, 2016. The presidential team recruited Caleb Maskell as Executive Secretary; Bryan Bademan as Assistant Secretary for Finances; and Andrew Hansen as Assistant Secretary for Membership, with Matt King as Webmaster/Digital Content Supervisor. This expanded leadership team stepped into their new roles at the January 2017 annual meeting in Denver. Over the past year, they have done outstanding work, bringing enhanced clarity to ASCH finances, membership records, communication, and internet presence. They have one additional year in their current appointment; ASCH’s incoming president, Ralph Keen, will oversee a search during 2018. 2) Conferences ASCH has navigated a shifting relationship with the AHA, following lengthy negotiations in 2016. We remain affiliated and continue to encourage co-sponsored annual meeting sessions, but ASCH is now hosting independent meetings next door to, rather than as part of, the AHA annual meeting. We were able to negotiate excellent hotel contracts in Washington D.C. (2018) and Chicago (2019); we obtained sleeping room rates lower than AHA could offer and free meeting room space (including space for our own book exhibit), within a few minutes’ walk of AHA headquarters’ hotels. -

Introduction

On the Law of Nature in the Three States of Life E. J. Hutchinson and Korey D. Maas Introduction Niels Hemmingsen (1513–1600) and the Development of Lutheran Natural-Law Teaching Because the Danish Protestant theologian and philosopher Niels Hemmingsen (1513–1600) is today little known outside his homeland, some of the claims made for his initial importance and continuing impact can appear rather extravagant. He is described, for example, not only as having “dominated” the theology of his own country for half a century1 but more broadly as having been “the greatest builder of systems in his generation.”2 In the light of this indefatigable system building, he has further been credited with (or blamed for) initiating modern trends in critical biblical scholarship,3 as well as for being “one of the founders 1 Lief Grane, “Teaching the People—The Education of the Clergy and the Instruction of the People in the Danish Reformation Church,” in The Danish Reformation against Its International Background, ed. Leif Grane and Kai Hørby (Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1990), 167. 2 F. J. Billeskov Janson, “From the Reformation to the Baroque,” in A History of Danish Literature, ed. Sven Hakon Rossel (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1993), 79. 3 Kenneth Hagen, “De Exegetica Methodo: Niels Hemmingsen’s De Methodis (1555),” in The Bible in the Sixteenth Century, ed. David C. Steinmetz (Durham: Duke University Press, 1990), 196. iii 595 Scholia iv Introduction of modern jurisprudence.”4 Illuminating this last claim especially are the more -

Ralph Keen CV

RALPH KEEN Department of History (MC 198) [email protected] University of Illinois at Chicago 319 400-8574 601 S. Morgan Street Chicago, IL 60607 EDUCATION Ph.D., History of Christianity, University of Chicago, 1990 M.A., Classics, Yale University, 1980 B.A., Greek, Columbia University, 1979 APPOINTMENTS Professor of History and Arthur Schmitt Foundation Chair of Catholic Studies, UIC, 2010- Assistant (1993-98) to Associate (1998-2010 ) Professor of Religious Studies, University of Iowa Visiting Associate Professor of the History of Christianity, Harvard Divinity School, Spring 2003 Newman Assistant Professor of Religion, Alaska Pacific University, 1991-93 POSTDOCTORAL HONORS AND AWARDS ICRU Research Award, University Honors Program, University of Iowa, 2009-10. Obermann Center for Advanced Studies, University of Iowa, 2008-09 Career Development Assignment, University of Iowa, 2008 International Programs Course Development Award, University of Iowa, 2008 International Programs Travel Grant, University of Iowa, 2006 Margaret Mann Phillips Lecturer, Erasmus of Rotterdam Society, 2004 Arts and Humanities Initiative Grant, University of Iowa, 2002 International Programs Travel Grant, University of Iowa, 2000 Miller Fund Traveling Award, University of Iowa, 1998 Developmental Leave, University of Iowa, 1996 Old Gold Summer Fellowship, University of Iowa, (1994 &) 1995 Forschungsstipendium, Herzog August Bibliothek, Wolfenbüttel, 1994-95 NEH Summer Stipend (for research at Columbia University), 1993 NEH Travel to Collections Grant (to Herzog August Bibliothek, Wolfenbüttel), 1991 Faculty Research Grant, Alaska Pacific University, 1992 Faculty Research Grant, H. H. Meeter Center for Calvin Studies, Grand Rapids, Mich., 1991 NEH Summer Seminar at Northwestern University, 1990 I. RESEARCH A. Books Exile and Restoration in Jewish Thought: An Essay in Interpretation. -

Appoint Interim Dean, Honors College, Chicago

3 Board Meeting September 10, 2015 APPOINT INTERIM DEAN, HONORS COLLEGE, CHICAGO Action: Appoint Interim Dean, Honors College Funding: State Appropriated Funds The Chancellor, University of Illinois at Chicago, and Vice President, University of Illinois, recommends the appointment of Ralph Keen, presently Arthur J. Schmitt Endowed Chair in Catholic Studies, Coordinator of Religious Studies, and Professor of History, College of Liberal Arts and Sciences, University of Illinois at Chicago, as Interim Dean, Honors College, non-tenured, on a twelve-month service basis, on 75 percent time, at an annual salary of $114,538 (equivalent to an annual nine-month base salary of $93,713 plus two-ninths annualization of $20,825), and an administrative increment of $15,284, for a salary of $129,822, beginning September 11, 2015. In addition, Dr. Keen will continue to hold the rank of Professor of History, College of Liberal Arts and Sciences, on indefinite tenure, on an academic year service basis, on 25 percent time, at an annual salary of $31,238, effective September 11, 2015; and Arthur J. Schmitt Endowed Chair in Catholic Studies, College of Liberal Arts and Sciences, non-tenured, on an academic year service basis, on zero percent time, non- salaried, effective September 11, 2015. While Dr. Keen serves as Interim Dean, he will receive additional compensation equivalent to 25 percent of two-ninths annualization 2 during the summer ($6,940 for summer 2016), for a total salary of $168,000. Dr. Keen was appointed as Interim Dean-Designate under the same conditions and salary arrangement, effective August 16, 2015. -

Introduction Introduction Introduction

Introduction Introduction Introduction We have only two substantial eyewitness accounts of the life of Martin Luther. Best known is a 9,000-word Latin memoir by Philip Melanchthon published in Latin at Heidelberg in 1548, two years after the Reformer’s death.1 In 1561, ‘Henry Bennet, Callesian’ translated this pamphlet into English; the martyro- logist John Foxe adopted Bennet’s text into his Memorials verbatim, including a number of the Englisher’s mistranslations. For example, where Melanchthon wrote that Luther nailed his 95 Theses to the door of the Castle Church in Wittenberg ‘pridie festi omnium Sanctorum’ – that is, ‘on the day before the feast of All Saints’ (31 October 1517) – Bennet mistranslated pridie as ‘after’ and wrote, ‘the morrowe after the feast of all Saynctes, the year. 1517.’ 2 Since every English church was obliged to own a copy of Foxe, Elizabethans – including William Shakespeare – believed Luther’s Reformation began on 2 November. The present volume corrects this and other Bennet/Foxe errors, and provides an authoritative English edition of Melanchthon’s Historia de Vita et Actis Reverendiss. Viri D. Mart. Lutheri, the first new translation in English to appear in print in many years.3 But the other substantial vita of Luther – at 175,000 words by far the longest and most detailed eyewitness account of the Reformer – has never been published in English. Recorded contemporaneously over the first twenty-five years of the Reformation by Luther’s lifelong antagonist Johannes Cochlaeus, the Commentaria de Actis et Scriptis Martini Lutheri was published in Latin at Mainz in 1549. -

The Humanistic, Fideistic Philosophy of Philip Melanchthon (1497-1560)

Marquette University e-Publications@Marquette Dissertations (2009 -) Dissertations, Theses, and Professional Projects The umH anistic, Fideistic Philosophy of Philip Melanchthon (1497-1560) Charles William Peterson Marquette University Recommended Citation Peterson, Charles William, "The umH anistic, Fideistic Philosophy of Philip Melanchthon (1497-1560)" (2012). Dissertations (2009 -). Paper 237. http://epublications.marquette.edu/dissertations_mu/237 THE HUMANISTIC, FIDEISTIC PHILOSOPHY OF PHILIP MELANCHTHON (1497-1560) by Charles W. Peterson, B.A., M.A., M. Div., S.T.M. A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School, Marquette University, in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Milwaukee, Wisconsin December 2012 ABSTRACT THE HUMANISTIC, FIDEISTIC PHILOSOPHY OF PHILIP MELANCHTHON (1497-1560): Charles W. Peterson, B.A., M.A., M.Div., S.T.M. Marquette University, 2012 This dissertation examines the way Philip Melanchthon, author of the Augsburg Confession and Martin Luther’s closest co-worker, sought to establish the relationship between faith and reason in the cradle of the Lutheran tradition, Wittenberg University. While Melanchthon is widely recognized to have played a crucial role in the Reformation of the Church in the sixteenth century as well as in the Renaissance in Northern Europe, he has in general received relatively little scholarly attention, few have attempted to explore his philosophy in depth, and those who have examined his philosophical work have come to contradictory or less than helpful conclusions about it. He has been regarded as an Aristotelian, a Platonist, a philosophical eclectic, and as having been torn between Renaissance humanism and Evangelical theology. An understanding of the way Melanchthon related faith and reason awaits a well-founded and accurate account of his philosophy. -

Columbia College Bulletin 2020-2021 03/29/21

Columbia College Columbia University in the City of New York Bulletin | 2020-2021 March 30, 2021 Chemistry ................................................................ 249 TABLE OF Classics ................................................................... 266 Colloquia, Interdepartmental Seminars, and Professional CONTENTS School Offerings ..................................................... 283 Comparative Literature and Society ........................ 286 Columbia College Bulletin ..................................................... 3 Computer Science ................................................... 297 Academic Calendar ................................................................. 6 Creative Writing ..................................................... 318 The Administration and Faculty of Columbia College .......... 10 Dance ...................................................................... 327 Admission ............................................................................. 55 Drama and Theatre Arts ......................................... 337 Fees, Expenses, and Financial Aid ....................................... 56 Earth and Environmental Sciences .......................... 350 Academic Requirements ....................................................... 87 East Asian Languages and Cultures ........................ 366 Core Curriculum ................................................................... 91 Ecology, Evolution, and Environmental Biology Literature Humanities .................................................... -

Thomas More on Humor

Travis Curtright Thomas More on Humor Thus, knowing that to move sport is lawful for an orator or anyone that shall talk in open assembly, good it were to know what compass he should keep that should thus be merry. thomas wilson, the art of rhetoric (1560) Thomas More married twice and both of his wives were short in stature. When asked the reason for this, More replied, “of two evils one should choose the less.”1 So reads a selection from the “witty sayings” of More, which Thomas Stapleton compiles in his 1588 biography. Though the quip could be apocryphal, it represents well enough what R. S. Sylvester calls More’s “sharp and ironic view of both himself and others,”2 a provocative deployment of wit, which More’s admirers often ignore and his critics frequently misunderstand. Indeed, whether to celebrate or condemn More’s humor was a subject during his own life and in the immediate years following his death. Erasmus writes of More’s “rare courtesy and sweetness of disposition,” which is so great that there is no one “so melancholy by nature that More does not enliven him.” According to Erasmus, More takes such pleasure in jesting that he seems born for it and “any logos 17:1 winter 2014 14 logos remark with more wit in it than ordinary always gave him pleasure, even if directed against himself.”3 Stapleton elaborates upon that sense of wit, writing how More’s “keen humor” functions in tandem with his “never-broken serenity” of mind and “constant peace and joy of his conscience.”4 So, too, even though Thomas Wilson was tried and imprisoned for heresy during the reign of Queen Mary, in his The Art of Rhetoric (1560), he calls attention to More’s facility in “pleasant delights, whose wit even at this hour is a wonder to all the world and shall be undoubtedly even unto the world’s end.”5 Most famous, perhaps, is the Sir Thomas More play (c. -

American Society of Church History Winter Meeting 2019 the Blackstone Hotel, Chicago, IL

American Society of Church History Winter Meeting 2019 The Blackstone Hotel, Chicago, IL ASCH 2019 Special Events at a Glance ASCH Conference Registration Art Hall (5th Floor) ASCH Book Exhibit Train Room Foyer (Concourse Level) Women’s Breakfast Friday, January 4, 7:15 AM 1600 Club / Lower Lounge The Women’s Breakfast is an opportunity for women scholars attending ASCH to gather for conversation and connection. Attendees will purchase their breakfast at the 1600 Club, and carry it to the Lower Lounge, a reserved private space to converse and connect. Society Awards Luncheon Friday, January 4, 12:00 PM – 1:30 PM ($30) Crystal Ballroom (4th Floor) This special lunch is an opportunity for us to come together as a community to celebrate our prizewinners and discuss the important mission and work of ASCH with presentations from our presidential leadership team. You are warmly encouraged to attend. Register when you purchase your conference registration, or (if you have already registered) by emailing Andrew Hansen ([email protected]). 1 Bus Tour of Religious Sites in Oak Park, IL Friday, January 4, 1:30 PM – 5:30 PM ($35) Tour Departs the Blackstone Hotel Lobby at 1:25 PM Dr. Daniel Sack and Dr. David Bains will lead a bus tour of religious sites in Oak Park, IL. The center of Oak Park is an ensemble of religious and civic sacred spaces, featuring churches that reflect the dominance of the village’s Protestant establishment. The keystone of this arrangement is Unity Temple, Frank Lloyd Wright’s first religious building and perhaps one of the best-known American church buildings of the 20th century.