Hidden Histories of Saint Paul's Architecture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bonding Request Update Sept. 2020

Twin Cities-Milwaukee-Chicago BONDING REQUEST Intercity Passenger Rail Service Project UPDATE SEPT. 2020 TCMC SECOND TRAIN RECEIVES $31.8 MILLION FEDERAL CAPITAL GRANT On Sept. 23, 2020, the US Secretary of Transportation announced a $31.8 million grant through the Federal Railroad Administration for Wisconsin and Minnesota to be used for final design and construction of freight rail track and signal improvements in and around Winona MN, La Crescent MN, and La Crosse WI. The improvements will accommodate the Twin Cities-Milwaukee-Chicago (TCMC) Second Train, a daily round trip passenger train between the Twin Cities and Chicago along the existing Amtrak Empire Builder route. This leaves the state of Minnesota as the only uncommitted partner in making the project a reality. TCMC CAPITAL BUDGET - MN TCMC CAPITAL BUDGET - WI TOTAL $26.9M Federal (COMMITTED) $4.9M Federal (COMMITTED) $31.8M Federal $10M Minnesota (NOT COMMITTED) $6.2M Wisconsin (COMMITTED) $16.2M Local $3.8M Amtrak (COMMITTED) $1.2M Amtrak (COMMITTED) $5M Amtrak $40.7M Minnesota Project Cost $12.3M Wisconsin Project Cost $53M Total Additional support: Federal Railroad Administration awarded $12.569 million to the project for startup operating costs, Amtrak has committed to capital upgrade of the Winona station platform, Canadian Pacific Railway fully supported the federal grant application for rail infrastructure improvements. Legislative Bonding Request $10 million is requested of the Minnesota Legislature. The state will receive, in return, more than $40 million in track and signal improvements in Winona and La Crescent, Minnesota that will benefit both freight and passenger rail. This request is urgent as the FRA expects Second Train project managers to secure matching funds and execute the grant agreement by September 30, 2021. -

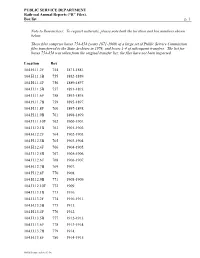

An Inventory of Its Railroad Annual Reports

PUBLIC SERVICE DEPARTMENT Railroad Annual Reports (“R” Files). Box list p. 1 Note to Researchers: To request materials, please note both the location and box numbers shown below. These files comprise boxes 754-858 (years 1871-1969) of a large set of Public Service Commission files transferred to the State Archives in 1976; and boxes 1-4 of subsequent transfers. The list for boxes 754-858 was taken from the original transfer list; the files have not been inspected. Location Box 104.H.11.2F 754 1871-1881. 104.H.11.3B 755 1882-1889. 104.H.11.4F 756 1889-1897. 104.H.11.5B 757 1891-1893. 104.H.11.6F 758 1893-1895. 104.H.11.7B 759 1895-1897. 104.H.11.8F 760 1897-1898. 104.H.11.9B 761 1898-1899. 104.H.11.10F 762 1900-1901. 104.H.12.1B 763 1901-1902. 104.H.12.2F 764 1902-1903. 104.H.12.3B 765 1903-1904. 104.H.12.4F 766 1904-1905. 104.H.12.5B 767 1905-1906. 104.H.12.6F 768 1906-1907. 104.H.12.7B 769 1907. 104.H.12.8F 770 1908. 104.H.12.9B 771 1908-1909. 104.H.12.10F 772 1909. 104.H.13.1B 773 1910. 104.H.13.2F 774 1910-1911. 104.H.13.3B 775 1911. 104.H.13.4F 776 1912. 104.H.13.5B 777 1912-1913. 104.H.13.6F 778 1913-1914. 104.H.13.7B 779 1914. 104.H.13.8F 780 1914-1915. -

Transportation on the Minneapolis Riverfront

RAPIDS, REINS, RAILS: TRANSPORTATION ON THE MINNEAPOLIS RIVERFRONT Mississippi River near Stone Arch Bridge, July 1, 1925 Minnesota Historical Society Collections Prepared by Prepared for The Saint Anthony Falls Marjorie Pearson, Ph.D. Heritage Board Principal Investigator Minnesota Historical Society Penny A. Petersen 704 South Second Street Researcher Minneapolis, Minnesota 55401 Hess, Roise and Company 100 North First Street Minneapolis, Minnesota 55401 May 2009 612-338-1987 Table of Contents PROJECT BACKGROUND AND METHODOLOGY ................................................................................. 1 RAPID, REINS, RAILS: A SUMMARY OF RIVERFRONT TRANSPORTATION ......................................... 3 THE RAPIDS: WATER TRANSPORTATION BY SAINT ANTHONY FALLS .............................................. 8 THE REINS: ANIMAL-POWERED TRANSPORTATION BY SAINT ANTHONY FALLS ............................ 25 THE RAILS: RAILROADS BY SAINT ANTHONY FALLS ..................................................................... 42 The Early Period of Railroads—1850 to 1880 ......................................................................... 42 The First Railroad: the Saint Paul and Pacific ...................................................................... 44 Minnesota Central, later the Chicago, Milwaukee and Saint Paul Railroad (CM and StP), also called The Milwaukee Road .......................................................................................... 55 Minneapolis and Saint Louis Railway ................................................................................. -

Transportation

TRANSPORTATION RAMSEY COUNTY COMPREHENSIVE PLAN 45 TRANSPORTATION KEY THEMES: ROADS AND HIGHWAYS Implement the county’s “All Abilities Transportation Network” Policy. Transportation and land use planning should be linked to ensure development that encourages transit ridership. Collaborate with municipalities on service delivery, right of way and access management issues. Planned capacity expansion of I-94, I-35W and Highway 36 by MnDOT. Reclassify Lexington Parkway to a Class A Minor Arterial and extend to Shepard Road in partnership with the City of Saint Paul. TRANSIT, BIKING AND WALKING Riverview Corridor, a modern streetcar line between Mall of America, the Airport and Downtown Saint Paul, will be in operation. Rush Line, a bus rapid transit line between Downtown Saint Paul and White Bear Lake, will be in operation. Gold Line, a bus rapid transit line between Downtown Saint Paul and Woodbury, will be in operation. The B Line, an arterial rapid bus line, between Saint Paul’s Midway and Minneapolis’ Uptown neighborhoods will be in operation. Add additional service at the Union Depot, including a second daily Amtrak trip to Chicago. Prioritize multi-modal transportation, including bicycling and walking. Trails will be coordinated at municipal, local, regional and state levels in order to form a comprehensive, All-Abilities system. RAMSEY COUNTY COMPREHENSIVE PLAN 46 TRANSPORTATION VISION Transportation decisions will be guided by the county’s All Abilities Transportation Network Policy. The Ramsey County Board of Commissioners is committed to creating and maintaining a transportation system that provides equitable access for all people regardless of race, ethnicity, age, gender, sexual preference, health, education, abilities, and economics. -

Of Minnesota for 1879. 427 Chapter Cccxviii. an Act

OF MINNESOTA FOR 1879. 427 CHAPTER CCCXVIII. AN ACT RELATING TO THE ST. PAUL UNION DEPOT COMPANY. Be U enacted by the Legislature of the State of Minnesota: SECTIOX 1. The said The St. Paul Union Depot Company, (a railroad corporation incorporated and organized under and in accordance with the general laws of this state,) may obtain the right of way over and across any lands needed for the construction of its railroad or tracks, and may obtain all necessary sites and grounds or land for its Union Passenger Depot or other buildings or appurtenances requisite for the proper carrying on of its busi- ness, in the manner and as provided in title one of chapter ihirty- fclir of the general statutes of the State of Minnesota as amended by an act of the Legislature of this State, entitled ''an act to amend title one of chapter thirty-four of the general statutes relating to corporations," approved March 1st, J872, being chapter fifty-three of the general laws of 1872, or as otherwise may be provided by law in such cases. Provided, that nothing herein contained shall pre- vent said corporation from purchasing, holding or disposing of any real estate which it may deem needtul or convenient for carrying on its business. And if it becomes necessary in the location or construction of the road or tracks of the above named corporation, or in the location or construction of its said Union Depot, or in other needful buildings or appurtenances, to occupy or use any depot or depot grounds or other land or any part of the railroad, or tracks of. -

The Watertown Express and the 'Hog and Human': Passenger Service In

Copyright © 1973 by the South Dakota State Historical Society. All Rights Reserved. Copyright © 1973 by the South Dakota State Historical Society. All Rights Reserved. The WATERTOWN EXPRESS and the "Hog and Human": M & StL Passenger Service in South Dakota 1884-1960 DONOVAN L. HOFSOMMER In mid-July of 1960 editors of the Minneapolis Tribune found much on the regional scene that they judged to be newsworthy: Minnesotans were heavily engaged in political debate anticipating the general elections of the coming fall; the Hill Lines were rebuffed in their attempts to consummate a huge railroad merger: the speeding AFTERNOON HIAWATHA was derailed near Saint Paul, resulting in injury to several persons; Minneapolitans were enjoying the annual Aquatennial Celebration; and it was hot. One important event was overlooked by the Minneapolis journalists, however. On 21 July passenger service by the Minneapolis & Saint Louis Railway between Minneapolis and Watertown, South Dakota, ended forever. At 10:30 P. M. on 20 July train number thirteen quietly slipped out of the trainsheds at the Great Northern depot in Minneapolis for the last time; its counterpart number fourteen had made its final departure from Watertown an hour and one-half earlier. Without hoopla and almost without notice, a seventy-six year tradition of service ended when these two trains reached their respective terminals in the misty morning hours of 21 July.' 1. Minneapolis Tribune, 9-22 July 1960; Watertown Public Opinion, 21 July 1960; Minneapolis & St. Louis Railway, Time Table No. 15, 6 December 1959 pp. 1-2, 11-12. Copyright © 1973 by the South Dakota State Historical Society. -

Saint Paul African American Historic and Cultural Context, 1837 to 1975

SAINT PAUL AFRICAN AMERICAN HISTORIC AND CULTURAL CONTEXT, 1837 TO 1975 Ramsey County, Minnesota May 2017 SAINT PAUL AFRICAN AMERICAN HISTORIC AND CULTURAL CONTEXT, 1837 TO 1975 Ramsey County, Minnesota MnHPO File No. Pending 106 Group Project No. 2206 SUBMITTED TO: Aurora Saint Anthony Neighborhood Development Corporation 774 University Avenue Saint Paul, MN 55104 SUBMITTED BY: 106 Group 1295 Bandana Blvd. #335 Saint Paul, MN 55108 PRINCIPAL INVESTIGATOR: Nicole Foss, M.A. REPORT AUTHORS: Nicole Foss, M.A. Kelly Wilder, J.D. May 2016 This project has been financed in part with funds provided by the State of Minnesota from the Arts and Cultural Heritage Fund through the Minnesota Historical Society. Saint Paul African American Historic and Cultural Context ABSTRACT Saint Paul’s African American community is long established—rooted, yet dynamic. From their beginnings, Blacks in Minnesota have had tremendous impact on the state’s economy, culture, and political development. Although there has been an African American presence in Saint Paul for more than 150 years, adequate research has not been completed to account for and protect sites with significance to the community. One of the objectives outlined in the City of Saint Paul’s 2009 Historic Preservation Plan is the development of historic contexts “for the most threatened resource types and areas,” including immigrant and ethnic communities (City of Saint Paul 2009:12). The primary objective for development of this Saint Paul African American Historic and Cultural Context Project (Context Study) was to lay a solid foundation for identification of key sites of historic significance and advancing preservation of these sites and the community’s stories. -

Feasibility Study (Started in January 2000) That Would Evaluate the Constraints and Opportunities of Operating Commuter Rail Service in the Red Rock Corridor

Table of Contents TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Executive Summary. E-1 1.0 Introduction . 1-1 1.1 Description of Red Rock Corridor . 1-1 1.2 Management . 1-2 1.3 Study Overview. 1-3 2.0 Public Involvement Program . 2-1 2.1 TAC and RRCC Meetings . 2-1 2.2 Open Houses. 2-1 2.3 Land Use Forum . 2-1 2.4 Station Area Planning Workshops . 2-2 2.5 Newsletters. 2-2 2.6 Web Site . 2-2 3.0 Purpose and Need . 3-1 3.1 Corridor Characteristics and Trends . 3-1 3.2 Project Need . 3-1 3.3 Goals, Objectives, and Criteria. 3-3 4.0 Alternatives Analysis . 4-1 4.1 Screening of Technology Options . 4-1 4.2 Summary of New FTA Rules for Major Capital Investments . 4-6 4.3 Definition of A Baseline Alternative . 4-8 4.4 Definition of a Build Alternative . 4-9 4.5 Intelligent Transportation System (ITS) Applications . 4-9 5.0 Station Area Planning . 5-1 5.1 Land Use Forum . 5-1 5.2 Station Area Planning Workshops . 5-2 6.0 Commuter Rail Service Plan . 6-1 6.1 Overview . 6-1 6.2 Initial Train Schedule Timetable . 6-4 6.3 Demand Forecast . 6-5 6.4 Rolling Stock . 6-6 6.5 Maintenance and Layover Facilities . 6-7 6.6 Capacity Improvements . 6-7 7.0 Financial Analysis . 7-1 7.1 Capital Costs . 7-1 7.2 Operating and Maintenance Costs . 7-3 7.3 Comparison to Other Rail Systems. -

The Life and Death of Gloster Depot

SPRING 2005 Newsletter of the Twin Cities Division, Thousand Lakes Region, National Model Railroad Association l www.twincitiesdivision.org The Life and Death of Gloster Depot By Marvin Mahre were sold at Gloster, but the poor con- ductors had to punch out many cash As reprinted from Northstar News, the fare receipts. Railway Express was also newsletter of the Northstar Chapter of the handled at the depot. National Railway Historical Society. The operators at Gloster had a unique [Editor's Note: Gladstone Depot was locat- set of manual gates they operated. The ed in present day Maplewood, near Frost & gates blocked either the NP or the Soo English streets - just feet from where the Line, depending on which way they were Division has its monthly meetings. The thrown. The NP block signals went red name Gloster was used because the Soo when the gates were against their main- Line had a depot in Gladstone, Michigan. line. The Soo Line had no block signals. Before Maplewood was incorporated in At one time, the operators tried to 1956, the area was known as "Gladstone."] time-slip extra pay for changing the posi- tion of the gates, but the railroad won Let's start about 1942, because that's that argument. These gates can be seen when I can remember the vivid details in John Cartwright's drawing of the better. Gloster Depot. The Gloster Depot was manned twenty- The Milwaukee freight train, in the days four hours per day (three tricks). Three of steam, had three helpers coming up freight railroads ran through Gloster. -

8. South Central Minnesota Passenger Rail Initiative.Pdf

8. Council Work Session Memorandum TO: City Council FROM: Tim Murray, City Administrator MEETING DATE: April 6, 2021 SUBJECT: South Central Minnesota Passenger Rail Initiative Discussion: A bill was introduced by Rep. Todd Lippert of Northfield this legislative session (HF 1393) that is requesting $500,000 in funding to prepare a feasibility study and alternatives analysis of a passenger rail corridor connecting Minneapolis and St. Paul to Albert Lea on existing rail line and passing through Faribault and Northfield. Northfield City Councilmember Suzie Nakasian recently reached out to Mayor Voracek regarding this initiative, and Northfield City Administrator Ben Martig has provided the materials they prepared in support of the bill. They are requesting that the Faribault City Council consider adopting a resolution to be submitted in support of the bill. A similar rail proposal was discussed in 2015, but was never funded so a feasibility study was never completed. Support for that proposal included the City of Faribault as well as 40+/- other stakeholders. Attachments: • HF 1393 and memo • Northfield 2021-03-16 Council Packet materials • 2021-03-09 Letter to Senator Draheim w/ attachments • Email correspondence 02/11/21 REVISOR KRB/LG 21-02773 This Document can be made available in alternative formats upon request State of Minnesota HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES NINETY-SECOND SESSION H. F. No. 1393 02/22/2021 Authored by Lippert and Hausman The bill was read for the first time and referred to the Committee on Transportation Finance and Policy 1.1 A bill for an act 1.2 relating to transportation; appropriating money for a passenger rail feasibility study 1.3 in southern Minnesota. 1.4 BE IT ENACTED BY THE LEGISLATURE OF THE STATE OF MINNESOTA: 1.5 Section 1. -

Saint Paul Union Depot Phase II Analysis

Summary Saint Paul Union Depot Phase II Analysis Prepared for Ramsey County Regional Railroad Authority By LTK Engineering Services in association with Bloom Consultants, LLC Nancy Whelan Consulting Richardson, Richter & Associates, Inc. Zimmer Gunsul Frasca Partnership November 24, 2003 Contact for additional information: Kathryn DeSpiegelaere, Director Ramsey County Regional Railroad Authority 665 Ramsey County Government Center West 50 West Kellogg Boulevard Saint Paul, Minnesota 55102 Phone 651 266 2762 [email protected] 2 Introduction The purpose of the Phase II study of Union Depot was to describe how several different modes of public transportation now serving, or proposed to serve, downtown St. Paul, Minnesota, can fit together in a thoughtfully designed multi-modal transit terminal located at Saint Paul Union Depot (see map illustrating location of Union Depot on Page 4). It follows a Phase I study that analyzed alternative locations for the multi-modal transit terminal and resulted in a preferred site location, that of St. Paul Union Depot. Union Depot offers the best opportunity for a facility that can meet the needs of the city, region and state, and enhance the role of St. Paul and the Twin Cities as a central place for the upper Midwest. Although the opportunity for creative reuse of a significant architectural monument is an obvious benefit of this concept, in fact the proposed terminal would be a modern facility, incorporating today’s and tomorrow’s transportation modes in a thoroughly contemporary way. It is the combination of modern functionality and stirring architecture that makes the Union Depot multi-modal transit facility concept so appealing. -

Union Depot User Count and Customer Survey: Final Report

TOURISM CENTER Union Depot User Count and Customer Survey: Final Report Authored by Xinyi Qian, Ph.D. Union Depot User Count and Customer Survey: Final Report September 16, 2016 Authored by Xinyi Qian, Ph.D., University of Minnesota Tourism Center Sponsor: Ramsey County Regional Railroad Authority (RCRRA) Reviewers: Jean Krueger, RCRRA Tina Volpe, JLL Editor: Elyse Paxton The University of Minnesota Tourism Center is a collaboration of University of Minnesota Extension and the College of Food, Agricultural and Natural Resource Sciences. © 2016 Regents of the University of Minnesota. All rights reserved. University of Minnesota Extension is an equal opportunity educator and employer. In accordance with the Americans with Disabilities Act, this material is available in alternative formats upon request. Direct requests to (612) 624-7165. Printed on recycled and recyclable paper with at least 10 percent postconsumer waste material. i Union Depot user count and customer survey Table of Contents List of Figures iii List of Tables i v Executive Summary v 1. INTRODUCTION 1 2. METHODOLOGY 1 Study setting 1 Sampling 2 Questionnaire 1 Customer survey response rate 2 Analysis 2 3. USER COUNT RESULTS 3 4 . CUSTOMER SURVEY RESULTS 5 Respondents 5 Union Depot visitation 1 1 5 . DISCUSSION 1 4 6. REFERENCES 16 7 . APPENDIX 17 ii Union Depot user count and customer survey List of Figures Figure 1: Full trade area of Union Depot customer survey respondents 9 Figure 2: Zoomed trade area map of Union Depot customer survey respondents 9 iii Union Depot user