The Love of Researc

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Eliza Calvert Hall: Kentucky Author and Suffragist

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Literature in English, North America English Language and Literature 2007 Eliza Calvert Hall: Kentucky Author and Suffragist Lynn E. Niedermeier Click here to let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Thanks to the University of Kentucky Libraries and the University Press of Kentucky, this book is freely available to current faculty, students, and staff at the University of Kentucky. Find other University of Kentucky Books at uknowledge.uky.edu/upk. For more information, please contact UKnowledge at [email protected]. Recommended Citation Niedermeier, Lynn E., "Eliza Calvert Hall: Kentucky Author and Suffragist" (2007). Literature in English, North America. 54. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/upk_english_language_and_literature_north_america/54 Eliza Calvert Hall Eliza Calvert Hall Kentucky Author and Suffragist LYNN E. NIEDERMEIER THE UNIVERSITY PRESS OF KENTUCKY Frontispiece: Eliza Calvert Hall, after the publication of A Book of Hand-Woven Coverlets. The Colonial Coverlet Guild of America adopted the work as its official book. (Courtesy DuPage County Historical Museum, Wheaton, 111.) Publication of this volume was made possible in part by a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities. Copyright © 2007 by The University Press of Kentucky Scholarly publisher for the Commonwealth, serving Bellarmine University, Berea College, Centre College of Kentucky, Eastern Kentucky University, The Filson Historical Society, Georgetown College, Kentucky Historical Society, Kentucky State University, Morehead State University, Murray State University, Northern Kentucky University, Transylvania University, University of Kentucky, University of Louisville, and Western Kentucky University. All rights reserved. Editorial and Sales Offices: The University Press of Kentucky 663 South Limestone Street, Lexington, Kentucky 40508-4008 www.kentuckypress.com 11 10 09 08 07 5 4 3 2 1 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Niedermeier, Lynn E., 1956- Eliza Calvert Hall : Kentucky author and suffragist / Lynn E. -

Lida (Eliza) Calvert Hall/Obenchain/Mcmillan/Godwin Collection

Website: www.rockwellantiquesdallas.com Email: [email protected] Ph: +1 (972) 679-3309 JUST ASK FOR NEVAN Lida (Eliza) Calvert Hall/Obenchain/McMillan/Godwin Collection It is our PLEASURE to INTRODUCE you to the Lida Calvert Hall/Obenchain/McMillan Collection. The Lida Calvert Hall/Obenchain/McMillan Collection is a large Privately held collection of many items of historic significance. The Collection is wide ranging in its content, from rare French Furniture pieces to Books and Manuscripts. The Collection consists of 5 generations of the Calvert Hall/Obenchain/McMillan and Godwin Families. The Story of this Collection starts with Eliza (Lida) Calvert Hall; Eliza Caroline "Lida" Obenchain (née Calvert), (February 11, 1856 - December 20, 1935) was an American author, women's rights advocate, and suffragist from Bowling Green, Kentucky. Lida Obenchain, writing under the pen name Eliza Calvert Hall, was widely known early in the twentieth century for her short stories featuring an elderly widowed woman, "Aunt Jane", who plainly spoke her mind about the people she knew and her experiences in the rural south. Lida Obenchain's best known work is ‘Aunt Jane of Kentucky’ which received extra notability when United States President Theodore Roosevelt recommended the book to the American people during a speech, saying, "I cordially recommend the first chapter of Aunt Jane of Kentucky as a tract in all families where the menfolk tend to selfish or thoughtless or overbearing disregard to the rights of their womenfolk”. In the Collection, we possess a number of letters that President Roosevelt sent to Lida praising her work, one on White House Stationary and others from when he left office. -

Deaccessions July 2013–June 2014

MUSEUM OF FINE ARTS, BOSTON Annual Report Deaccessions July 2013–June 2014 Asia & Africa/African Object No. Artist Title Culture/Date/Place Medium Credit Line 1. 1991.1065 Head African, Edo peoples, Terracotta, traces of Gift of William E. and Bertha L. Teel Nigeria, Benin pigment kingdom, about 1750 Benin City, Nigeria 2. 1996.383a-c Memorial screen (duen fubara) African, Ijaw Kalabari Wood, pigments, Gift of William E. and Bertha L. Teel peoples, Nigeria, late fiber 19th century Ancient/Classical Object No. Artist Title Culture/Date/Place Medium Credit Line 1. 64.1195 Coin of Sibidunda with bust of Roman Provincial, Bronze Theodora Wilbour Fund in memory Gordian III Imperial Period, A.D. of Zoë Wilbour 238–244 Asia: Phrygia, Sibidunda Ancient/Egyptian Object No. Artist Title Culture/Date/Place Medium Credit Line 1. 19.3387 Bowl with incised decoration Nubian, A-Group to Pottery Archaeological Survey of Nubia C-Group, 3100–1550 B.C. Nubia, Egypt, el-Dakka, Cemetery 101, Grave 28 2. 20.3105 Miniature black-topped red Nubian, Classic Kerma, Pottery Harvard University–Boston polished beaker about 1700–1550 B.C. Museum of Fine Arts Expedition Nubia, Sudan, Kerma, Cemetery S, Tumulus IV, grave 425 3. 20.3170 Black-topped red polished beaker Nubian, Classic Kerma, Pottery Harvard University–Boston about 1700–1550 B.C. Museum of Fine Arts Expedition Nubia, Sudan, Kerma, Cemetery S, Tumulus III, grave 308 Annual Report Deaccessions July 2013–June 2014 Page 2 of 39 Ancient/Egyptian Object No. Artist Title Culture/Date/Place Medium Credit Line 4. 21.3009 Shawabty of King Taharqa Nubian, Napatan Gray serpentinite Harvard University—Boston Period, reign of Museum of Fine Arts Expedition Taharqa, 690–664 B.C. -

Woven Coverlets Tell Story of Past

Woven Coverlets Tell Story of Past Nancy Ostman, February 22, 2014 Photo caption: This 1832 woven coverlet was made by Archibald Davidson, a Scottish weaver who came to Ithaca in the late 1820s. Woven coverlets made in the U.S. pre-Civil War era were used as bed coverings. They were made of wool and cotton (or occasionally wool and linen) on floor looms by hand. Coverlets were woven of two or more colors, made to be reversible with a light and dark color pattern showing as a negative on the back side. The earliest era of coverlet making, judging from surviving pre-Revolutionary War period to 1820 examples, was a household craft practiced by women or itinerant weavers who used narrow looms that produced simple geometric designs. The boom in coverlet making was fueled by Joseph Marie Jacquard’s 1801 invention of a computer-like attachment to looms which picked up each warp (lengthwise) thread individually. This meant that elaborate “fancy” patterns could be woven. To make fancy coverlets, an expensive loom attachment was required. Thus, most coverlet making between 1820 and 1860 was generally practiced by men, who wove for clients in solitary to 6-person “factories” or workshops. Many weavers were born and trained in Europe. These Scotch, Irish, English, Dutch, and Germans came to the U.S. to practice their trade, as they were pushed out of business in Europe, where the industrial revolution occurred earlier than in the U.S. Once in the U.S., immigrant weavers often moved beyond coastal cities, where industrialization already had begun, to rural towns of New York, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania. -

India's Textile and Apparel Industry

Staff Research Study 27 Office of Industries U.S. International Trade Commission India’s Textile and Apparel Industry: Growth Potential and Trade and Investment Opportunities March 2001 Publication 3401 The views expressed in this staff study are those of the Office of Industries, U.S. International Trade Commission. They are not necessarily the views of the U.S. International Trade Commission as a whole or any individual commissioner. U.S. International Trade Commission Vern Simpson Director, Office of Industries This report was principally prepared by Sundar A. Shetty Textiles and Apparel Branch Energy, Chemicals, and Textiles Division Address all communications to Secretary to the Commission United States International Trade Commission Washington, DC 20436 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Executive Summary . v Chapter 1. Introduction . 1-1 Purpose of study . 1-1 Data and scope . 1-1 Organization of study . 1-2 Overview of India’s economy . 1-2 Chapter 2. Structure of the textile and apparel industry . 2-1 Fiber production . 2-1 Textile sector . 2-1 Yarn production . 2-4 Fabric production . 2-4 Dyeing and finishing . 2-5 Apparel sector . 2-5 Structural problems . 2-5 Textile machinery . 2-7 Chapter 3. Government trade and nontrade policies . 3-1 Trade policies . 3-1 Tariff barriers . 3-1 Nontariff barriers . 3-3 Import licensing . 3-3 Customs procedures . 3-5 Marking, labeling, and packaging requirements . 3-5 Export-Import policy . 3-5 Duty entitlement passbook scheme . 3-5 Export promotion capital goods scheme . 3-5 Pre- and post-shipment financing . 3-6 Export processing and special economic zones . 3-6 Nontrade policies . -

Notable Southern Families Vol II

NOTABLE SOUTHERN FAMILIES VOLUME II (MISSING PHOTO) Page 1 of 327 NOTABLE SOUTHERN FAMILIES VOLUME II JEFFERSON DAVIS PRESIDENT OF THE CONFEDERATE STATES OF AMERICA Page 2 of 327 NOTABLE SOUTHERN FAMILIES VOLUME II Copyright 1922 By ZELLA ARMSTRONG Page 3 of 327 NOTABLE SOUTHERN FAMILIES VOLUME II NOTABLE SOUTHERN FAMILIES VOLUME II COMPILED BY ZELLA ARMSTRONG Member of the Tennessee Historical Commission PRICE $4.00 PUBLISHED BY THE LOOKOUT PUBLISHING CO. CHATTANOOGA, TENN. Page 4 of 327 NOTABLE SOUTHERN FAMILIES VOLUME II Table of Contents FOREWORD....................................................................10 BEAN........................................................................11 BOONE.......................................................................19 I GEORGE BOONE...........................................................20 II SARAH BOONE...........................................................20 III SQUIRE BOONE.........................................................20 VI DANIEL BOONE..........................................................21 BORDEN......................................................................23 COAT OF ARMS.............................................................29 BRIAN.......................................................................30 THIRD GENERATION.........................................................31 WILLIAM BRYAN AND MARY BOONE BRYAN.......................................33 WILLIAM BRYAN LINE.......................................................36 FIRST GENERATION -

Medical Prepayment Berg, Head of the Department of Neurology at the University Probing the Allegedly Power of Ilhnoia

’^ M P P P W i!! *.1 iJ- „ prvV T ^ ' ^ ' r z : ’ “i: ' •• i p f f - ' •’ r.. ' -1^4^ . • ^4-, / ' y ,. I ?4r ^ • . t '- __ V WEDNESDAY, DECEMBER 1^, 19te AT«ra»t Daily Net PrcM Ron THIRTY-TWO iKanrliMpf ^pralb Far tlM EaM The Weather V Dec. U , IMS Feeaeatft a< O. •. Weather S o n M 10,835 Partly cloudy, colder ioelcfet. Member « f tkm Ammt Friday fair and coMcr. BareM of CtrcvUttMM ' Mancheater^A City of Villoite Charm __________ ' -V________________ VOL. LXXII, NO. 67 (GeaU ned ah PaGo tS) MANCHESTER, CONN^ THURSDAY, DECEMBER 18,; 1952 (TWENTY-POUR PAGES—IN TWO SECTIONS) PRICE n V E CENTS Siamese Twin Grime Lord Faces Quiz By, Probers V - S | - Chicago, Dec. 18— (/P)—One of the Siamese twins separated New York, Dec. 18—(A*)— Wednesday in a history makinG operation was “dolAG badly” The New York State Crime ny-ron today and physicians doubted he would survive. Dr. Eric Old- commission today began Medical Prepayment berG, head of the department of neuroloGy at the University probinG the alleGedly power of IlHnoia. said surGeons “ had to^ ful ‘fule of Albert Anastasia make a choice" durinG the day and his Murder, Inc., hench lonG eurgteial operation and that Kodney Dee, the tmallcr of the men on the Brooklyn water After Their Korean G>nferei|ce 'twins, waa Given the beneflt be- France Set front. ‘ cause he showed the Greater Anutula, reputed lord hiGh ex fc> r ‘ 'chance for ultimate survival. ecutioner of the eld Murder, Inc., Program Seeks SinGle Brain CoverinG T o Remove mob and one of tha few men alive OtdberG said surgeonn''Tound the to come hack from the SiqG SinG twins had only a sinGle fused outer duU i houM, is expected to be hail brain coverinG containinG a sinGle ed before the commluion, perhaps 'snGtdtal sinus'i'vein' that drains T u n is B ey today. -

Local Color's Finest Hour: Kentucky Literature at the Turn of the Twentieth Century

Eastern Kentucky University Encompass Online Theses and Dissertations Student Scholarship January 2014 Local Color's Finest Hour: Kentucky Literature at the Turn of the Twentieth Century Brian Clay Johnson Eastern Kentucky University Follow this and additional works at: https://encompass.eku.edu/etd Part of the Literature in English, North America Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Johnson, Brian Clay, "Local Color's Finest Hour: Kentucky Literature at the Turn of the Twentieth Century" (2014). Online Theses and Dissertations. 282. https://encompass.eku.edu/etd/282 This Open Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at Encompass. It has been accepted for inclusion in Online Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Encompass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LOCAL COLOR’S FINEST HOUR: KENTUCKY LITERATURE AT THE TURN OF THE TWENTIETH CENTURY By Brian Clay Johnson Bachelor of Arts Eastern Kentucky University Richmond, Kentucky 2012 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Eastern Kentucky University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS December, 2014 Copyright © Brian Clay Johnson, 2014 All rights reserved ii ABSTRACT This thesis takes into consideration literature created by various authors during the period 1890 to 1910, the turn of the twentieth century. This thesis looks specifically at the works produced during that time period by authors from Kentucky, living in Kentucky, or with strong ties to the state. The texts themselves illustrated these ties, as they all focused on or related to Kentucky at the time. -

Kentucky Humanities Redesign.Qk

$3.00 April 2008 KentuckyKentucky Humanities Council Inc. humanities Standing Up for Her Sex page 7 Eliza Calvert Hall of Bowling Green was an uncompromising advocate for women’s rights, and she relished a good fight. “Sally Ann’s Experience” page 14 In 1898, many magazines found Eliza Calvert Hall’s most famous short story too hot to handle. A Killing Gentleman page 27 The dueling ground was familiar territory for Alexander McClung, the feared Black Knight of the South. Plus: Our Lincoln Triumphs Photography by Don Ament Extraordinary Kentuckians—Famous, and Not Dear Friends, On pages 34-35 of this issue of Kentucky Humanities, you’ll see a report on Our Lincoln, the musical and dramatic extravaganza we presented in February to mark the beginning of Kentucky’s celebration of Abraham Lincoln’s 200th birthday. Forgive our immodesty, but we think it was terrific, and a sold-out house at the Singletary Center for the Arts in Lexington seemed to agree. Lincoln, Kentucky’s greatest son, is the most written-about American who ever lived. His greatness is unquestioned, and it’s appropriate for the Council and the Commonwealth to go all out for his bicentennial on February 12, 2009. Over the next two years, we will try to help Kentuckians gain a deeper understanding of Lincoln and his legacy—Lin- coln project grants, Chautauqua performances in communities and schools, and special publications are some of the ways we’ll do it. But if the list of extraordinary Kentuckians begins with Lincoln, it hardly ends with him. In this issue of our magazine, you’ll meet a worthy but largely forgotten member of the extraordinary Kentuckians club—a compelling “unknown” named Eliza Calvert Hall. -

Download the Entire Book As

half moon bay, california TooFar Media 500 Stone Pine Road, Box 3169 Half Moon Bay, CA 94019 © 2020 by Rich Shapero All Rights Reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. This is a book of fiction, and none of the characters are intended to portray real people. Names, characters, places and incidents are either the products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available. ISBN: 978-1-7335259-4-7 Cover artwork by Ramón Alejandro Cover design by Adde Russell and Michael Baron Shaw Artwork copyright © 2015 Rich Shapero Additional graphics: Sky Shapero 23 22 21 20 1 2 3 4 5 Also by Rich Shapero Balcony of Fog Rin, Tongue and Dorner Arms from the Sea The Hope We Seek Too Far Wild Animus 1 e float together—unborn twins with shrinking tails and mucid limbs, clasping each other in an inky blur. Your shoulders glisten with garnet bub- Wbles. Around your head, a halo of pearls; and as you nod, crepes of silk, onyx and gleaming, fold and furl. Roll in my arms, and I’ll roll in yours, sheltered, fearless, gloating over our foodless feast; decked in treasure, enthroned together, our ivory serpents twisting between. “The moment looms. We shudder, we shake. Nestling, squeezing, our artless bodies heave and convulse, and the rapture begins. A helpless frenzy, our violent trance, familiar, expected, but never the same. -

![IS 2364 (1987): Glossary of Textile Terms - Woven Fabrics [TXD 1: Physical Methods of Tests]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9982/is-2364-1987-glossary-of-textile-terms-woven-fabrics-txd-1-physical-methods-of-tests-2879982.webp)

IS 2364 (1987): Glossary of Textile Terms - Woven Fabrics [TXD 1: Physical Methods of Tests]

इंटरनेट मानक Disclosure to Promote the Right To Information Whereas the Parliament of India has set out to provide a practical regime of right to information for citizens to secure access to information under the control of public authorities, in order to promote transparency and accountability in the working of every public authority, and whereas the attached publication of the Bureau of Indian Standards is of particular interest to the public, particularly disadvantaged communities and those engaged in the pursuit of education and knowledge, the attached public safety standard is made available to promote the timely dissemination of this information in an accurate manner to the public. “जान का अधकार, जी का अधकार” “परा को छोड न 5 तरफ” Mazdoor Kisan Shakti Sangathan Jawaharlal Nehru “The Right to Information, The Right to Live” “Step Out From the Old to the New” IS 2364 (1987): Glossary of textile terms - Woven fabrics [TXD 1: Physical Methods of Tests] “ान $ एक न भारत का नमण” Satyanarayan Gangaram Pitroda “Invent a New India Using Knowledge” “ान एक ऐसा खजाना > जो कभी चराया नह जा सकताह ै”ै Bhartṛhari—Nītiśatakam “Knowledge is such a treasure which cannot be stolen” IS : 2364 - 1987 Indian Standard GLOSSARY OF TEXTILE TERMS- WOVEN FABRICS ( Second Revision ) ULX 001-4 : 677.074 Q C’ojpright 1988 BUREAU OF INDIAN STANDARDS MANAK BHAVAN, 9 BAHADUR SHAH ZAFAR MARG NEW DELHI 110002 Gr 7 Alay 1988 IS : 2364 - 1987 Indian Standard GLOSSARYOFTEXTILETERMS- WOVENFABRICS (Second Revision ) 0. FOREWORD 0.1 This Indian Standard ( Revised ) was adopted based on the prevalent practices and usage in the by the Bureau of Indian Standards on 10 Novem- Indian textile industry and trade, and are of tech- ber 1987, after the draft finalized by the Physical nical nature and need not necessarily tally with Methods of Test Sectional Committee had been those coined by excise or customs departments for approved by the Textile Division Council. -

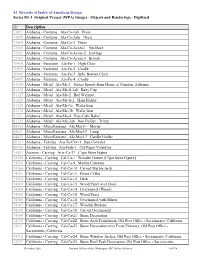

Images - Objects and Renderings - Digitized

44 Records of Index of American Design Series D1-3 Original Project (WPA) Images - Objects and Renderings - Digitized ID Description 73097 Alabama - Costume Ala-Co-1ab Dress 73098 Alabama - Costume Ala-Co-2abc Dress 73099 Alabama - Costume Ala-Co-3 Dress 73100 Alabama - Costume Ala-Co-Acces-1 Necklace 73101 Alabama - Costume Ala-Co-Acces-2 Earrings 73102 Alabama - Costume Ala-Co-Acces-3 Brooch 76904 Alabama - Furniture Ala-Fu-1 High Chair 76905 Alabama - Furniture Ala-Fu-2 Cradle 76906 Alabama - Furniture Ala-Fu-3 Split Bottom Chair 76907 Alabama - Furniture Ala-Fu-4 Cradle 81325 Alabama - Metal Ala-Me-1 Gutter Spouts from House at Camden, Alabama 81326 Alabama - Metal Ala-Me-S-1ab Baby Cup 81327 Alabama - Metal Ala-Me-2 Bed Warmer 81328 Alabama - Metal Ala-Me-S-2 Ham Holder 81329 Alabama - Metal Ala-Me-3a Wafer Iron 81330 Alabama - Metal Ala-Me-3b Wafer Iron 81331 Alabama - Metal Ala-Me-4 Hoe-Cake Baker 81332 Alabama - Metal Ala-Me-5ab Iron Holder - Trivet 84450 Alabama - Miscellaneous Ala-Mscl-1 Mortar 84451 Alabama - Miscellaneous Ala-Mscl-2 Lamp 84452 Alabama - Miscellaneous Ala-Mscl-3 Candle Holder 88707 Alabama - Textiles Ala-Te-Cov-1 Bed Coverlet 88708 Alabama - Textiles Ala-Emb-1 Cut Paper Valentine 74357 Arizona - Carving Ariz-Ca-37 Cigar Store Figure 74358 California - Carving Cal-Ca-1 Wooden Hunter [Cigar Store Figure] 74359 California - Carving Cal-Ca-9 Marble Columns 74360 California - Carving Cal-Ca-10 Carved Marble Arch 74361 California - Carving Cal-Ca-11 Horse Collar 74362 California - Carving Cal-Ca-12 Desk 74363 California