The Evolution of the Built Environment of the Margi Ethnic Group of Northeastern Nigeria

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Politics of History in Northern Nigeria

The Politics of History in Northern Nigeria Niels Kastfelt Centre of African Studies University of Copenhagen Paper presented to the Research Seminar of the African Studies Centre, Leiden, 27 April 2006 The Politics of History in Contemporary Africa In recent years there has been a growing interest in the political uses of history in Africa. It is difficult to tell whether there is today a greater or more explicit political use of history than before, but it is clear that the past as a political resource does attract a strong interest from politicians and others, and that this interest takes new and highly visible forms. In this paper I shall discuss the politics of history in northern Nigeria. The discussion is based on a local case from the Nigerian Middle Belt which will be interpreted in the light of two wider contexts, that of the African continent in general and that of the specific Nigerian context. The aim of the paper is therefore double, aiming both at throwing light on the continental debate on history and on contemporary Nigerian politics. The political use of history in contemporary Africa takes many forms and so does the scholarly study of it. Without pretending to cover the entire field some main forms may be identified: “Patriotic history”: In a series of fascinating studies Terence Ranger and others have called attention to the emergence of “patriotic history” in contemporary Zimbabwe1. Zimbabwean “patriotic history” is part of the so-called “Mugabeism” launched in recent years by the regime of Robert Mugabe. The core of Mugabeism is the special version of the past called patriotic history which is promoted systematically through television, radio, newspapers and in the schools. -

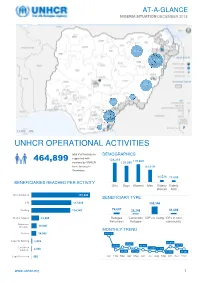

Unhcr Operational Activities 464,899

AT-A-GLANCE NIGERIA SITUATION DECEMBER 2018 28,280 388,208 20,163 1,770 4,985 18.212 177 Bénéficiaires Reached UNHCR OPERATIONAL ACTIVITIES total # of individuals DEMOGRAPHICS supported with 464,899 128,318 119,669 services by UNHCR 109,080 from January to 81,619 December; 34,825 of them from Mar-Apr 14,526 11,688 2018 BENEFICIARIES REACHED PER ACTIVITY Girls Boys Women Men Elderly Elderly Women Men Documentation 172,800 BENEFICIARY TYPE CRI 117,838 308,346 Profiling 114,747 76,607 28,248 51,698 Shelter Support 22,905 Refugee Cameroon IDPs in Camp IDPs in host Returnees Refugee community Awareness Raising 16,000 MONTHLY TREND Referral 14,956 140,116 Capacity Building 2,939 49,819 39,694 24,760 25,441 34,711 Livelihood 11,490 11,158 Support 2,048 46,139 37,118 13,770 30,683 Legal Protection 666 Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec www.unhcr.org 1 NIGERIA SITUATION AT-A-GLANCE / DEC 2018 CORE UNHCR INTERVENTIONS IN NIGERIA UNHCR Nigeria strategy is based on the premise that the government of Nigeria assumes the primary responsibility to provide protection and assistance to persons of concern. By building and reinforcing self-protection mechanisms, UNHCR empowers persons of concern to claim their rights and to participate in decision-making, including with national and local authorities, and with humanitarian actors. The overall aim of UNHCR Nigeria interventions is to prioritize and address the most serious human rights violations, including the right to life and security of persons. -

P E E L C H R Is T Ian It Y , Is L a M , an D O R Isa R E Lig Io N

PEEL | CHRISTIANITY, ISLAM, AND ORISA RELIGION Luminos is the open access monograph publishing program from UC Press. Luminos provides a framework for preserving and rein- vigorating monograph publishing for the future and increases the reach and visibility of important scholarly work. Titles published in the UC Press Luminos model are published with the same high standards for selection, peer review, production, and marketing as those in our traditional program. www.luminosoa.org Christianity, Islam, and Orisa Religion THE ANTHROPOLOGY OF CHRISTIANITY Edited by Joel Robbins 1. Christian Moderns: Freedom and Fetish in the Mission Encounter, by Webb Keane 2. A Problem of Presence: Beyond Scripture in an African Church, by Matthew Engelke 3. Reason to Believe: Cultural Agency in Latin American Evangelicalism, by David Smilde 4. Chanting Down the New Jerusalem: Calypso, Christianity, and Capitalism in the Caribbean, by Francio Guadeloupe 5. In God’s Image: The Metaculture of Fijian Christianity, by Matt Tomlinson 6. Converting Words: Maya in the Age of the Cross, by William F. Hanks 7. City of God: Christian Citizenship in Postwar Guatemala, by Kevin O’Neill 8. Death in a Church of Life: Moral Passion during Botswana’s Time of AIDS, by Frederick Klaits 9. Eastern Christians in Anthropological Perspective, edited by Chris Hann and Hermann Goltz 10. Studying Global Pentecostalism: Theories and Methods, by Allan Anderson, Michael Bergunder, Andre Droogers, and Cornelis van der Laan 11. Holy Hustlers, Schism, and Prophecy: Apostolic Reformation in Botswana, by Richard Werbner 12. Moral Ambition: Mobilization and Social Outreach in Evangelical Megachurches, by Omri Elisha 13. Spirits of Protestantism: Medicine, Healing, and Liberal Christianity, by Pamela E. -

Some Principles of the Use of Macro-Areas Language Dynamics &A

Online Appendix for Harald Hammarstr¨om& Mark Donohue (2014) Some Principles of the Use of Macro-Areas Language Dynamics & Change Harald Hammarstr¨om& Mark Donohue The following document lists the languages of the world and their as- signment to the macro-areas described in the main body of the paper as well as the WALS macro-area for languages featured in the WALS 2005 edi- tion. 7160 languages are included, which represent all languages for which we had coordinates available1. Every language is given with its ISO-639-3 code (if it has one) for proper identification. The mapping between WALS languages and ISO-codes was done by using the mapping downloadable from the 2011 online WALS edition2 (because a number of errors in the mapping were corrected for the 2011 edition). 38 WALS languages are not given an ISO-code in the 2011 mapping, 36 of these have been assigned their appropri- ate iso-code based on the sources the WALS lists for the respective language. This was not possible for Tasmanian (WALS-code: tsm) because the WALS mixes data from very different Tasmanian languages and for Kualan (WALS- code: kua) because no source is given. 17 WALS-languages were assigned ISO-codes which have subsequently been retired { these have been assigned their appropriate updated ISO-code. In many cases, a WALS-language is mapped to several ISO-codes. As this has no bearing for the assignment to macro-areas, multiple mappings have been retained. 1There are another couple of hundred languages which are attested but for which our database currently lacks coordinates. -

Iom Shelter Needs Assessment in Return Areas: Adamawa State

International Organization for Migration IOM SHELTER NEEDS ASSESSMENT IN RETURN AREAS: ADAMAWA STATE October 2017 Shelter Needs Assessment Report IOM Shelter Needs Assessment in Return Areas: Adamawa State Table of Content BACKGROUND ……………………………………………………………………………………….. 2 OBJECTIVE ……………………………………………………………………………………….. 2 COVERAGE ……………………………………………………………………………………….. 3 METHODOLOGY ……………………………………………………………………………….. 5 FINDINGS AND ANALYSIS Demographic Profile …………………………………………………………………………. 6 Housing, Land and Property ………………………………………………………………… 13 Housing Condition ……………………………………………………………………………18 Damage Assessment …………………………………………………………………………22 Access to Other Services …………………………………………………………………….29 RECOMMENDATIONS …………………………………………………………………………. 35 Page 1 IOM Shelter Needs Assessment in Return Areas: Adamawa State BACKGROUND In North-Eastern Nigeria, attacks and counter attacks have resulted in prolonged insecurity and endemic violations of human rights, triggering waves of forced displacement. Almost two million people remain displaced in Nigeria, and displacement continues to be a significant factor in 2017. Since late 2016, IOM and other humanitarian partners have been able to scale up on its activities. However, despite the will and hope of the humanitarian community and the Government of Nigeria and the dedication of teams and humanitarian partners in supporting them, humanitarian needs have drastically increased and the humanitarian response needs to keep scaling up to reach all the affected population in need. While the current humanitarian -

Maiduguri: City Scoping Study

MAIDUGURI: CITY SCOPING STUDY By Marissa Bell and Katja Starc Card (IRC) June 2021 MAIDUGURI: CITY SCOPING STUDY 2 Maiduguri is the largest city in north east Nigeria and the capital of Borno State, which suffers from endemic poverty, and capacity and legitimacy gaps in terms of its governance. The state has been severely affected by the Boko Haram insurgency and the resulting insecurity has led to economic stagnation in Maiduguri. The city has borne the largest burden of support to those displaced by the conflict. The population influx has exacerbated vulnerabilities that existed in the city before the security and displacement crisis, including weak capacities of local governments, poor service provision and high youth unemployment. The Boko Haram insurgency appears to be attempting to fill this gap in governance and service delivery. By exploiting high levels of youth unemployment Boko Haram is strengthening its grip around Maiduguri and perpetuating instability. Maiduguri also faces severe environmental challenges as it is located in the Lake Chad region, where the effects of climate change increasingly manifesting through drought and desertification. Limited access to water and poor water quality is a serious issue in Maiduguri’s vulnerable neighborhoods. A paucity of drains and clogging leads to annual flooding in the wet season. As the population of Maiduguri has grown, many poor households have been forced to take housing in flood-prone areas along drainages due to increased rent prices in other parts of the city. URBAN CONTEXT Maiduguri is the oldest town in north eastern Nigeria and has long served as a commercial centre with links to Niger, Cameroon and Chad and to nomadic communities in the Sahara. -

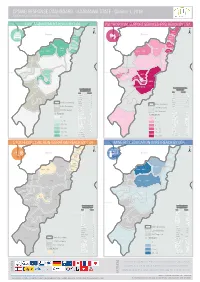

CPSWG RESPONSE DASHBOARD - ADAMAWA STATE - Quarter 1, 2019 Child Protection Sub Working Group, Nigeria

CPSWG RESPONSE DASHBOARD - ADAMAWA STATE - Quarter 1, 2019 Child Protection Sub Working Group, Nigeria YobeCASE MANAGEMENT REACH BY LGA PSYCHOSOCIALYobe SUPPORT SERVICES (PSS) REACH BY LGA 78% 14% Madagali ± Madagali ± Borno Borno Michika Michika 86% 10% 82% 16% Mubi North Mubi North Hong 100% Mubi South 5% Hong Gombi 100% 100% Gombi 10% 27% Mubi South Shelleng Shelleng Guyuk Song 0% Guyuk Song 0% 0% Maiha 0% Maiha Chad Chad Lamurde 0% Lamurde 0% Nigeria Girei Nigeria Girei 36% 81% 11% 96% Numan 0% Numan 0% Yola North Demsa 100% Demsa 26% Yola North 100% 0% Adamawa Fufore Yola South 0% Yola South 100% Fufore Mayo-Belwa Mayo-Belwa Adamawa Local Government Area Local Government (LGA) Target Area (LGA) Target LGA TARGET LGA TARGET Demsa 1,170 DEMSA 78 Fufore 370 Jada FUFORE 41 Jada Ganye 0 GANYE 0 Girei 933 GIREI 16 Gombi 4,085 State Boundary GOMBI 33 State Boundary Guyuk 0 GUYUK 0 LGA Boundary Hong 16,941 HONG 6 Ganye Ganye LGA Boundary Jada 0 JADA 0 Not Targeted Lamurde 839 LAMURDE 6 Not Targeted Madagali 6,321 MADAGALI 119 % Reach Maiha 2,800 MAIHA 12 % REACH Mayo-Belwa 0 0 MAYO - BELWA 0 0 Michika 27,946 Toungo 0% MICHIKA 232 Toungo 0% 1 - 36 Mubi North 11,576 MUBI NORTH 154 1 - 5 Mubi South 11,821 MUBI SOUTH 139 37 - 78 Numan 2,250 NUMAN 14 6 - 11 Shelleng 0 SHELLENG 0 79 - 82 12 - 16 Song 1,437 SONG 21 Teungo 25 83 - 86 TOUNGO 6 17 - 27 Yola North 1,189 YOLA NORTH 14 Yola South 2,824 87 - 100 YOLA SOUTH 47 28 - 100 SOCIO-ECONOMICYobe REINTEGRATION REACH BY LGA MINEYobe RISK EDUCATION (MRE) REACH BY LGA Madagali Madagali R 0% I 0% ± -

17 the Impact of Boko Haram Insurgency on Livestock Production

The Impact of Boko Haram Insurgency on Livestock Production in Mubi Region of Adamawa State, Nigeria. Augustine, C1., Daniel, J.D.2, Abdulrahman, B.S.1 Lubele, M.I.3, Katsala,. J.G.4 and Ardo, M.U.4 1. Department of Animal Production, Adamawa State University, Mubi. 2. Department of Agricultural Economics and Extension, Adamawa State University, Mubi. 3. Department of History, Adamawa State University, Mubi. 4. Department of Agricultural Education, College of Education, Hong. Abstract: This study was conducted to examine the impact of Boko Haram insurgence on livestock production in Mubi region of Adamawa State, Nigeria. Four local government areas (Mubi north, Mubi south, Madagali and Michika) were purposely selected for this study. Thirty (30) livestock farmers were randomly selected from each of the local government area making a total of one hundred and twenty (120) respondents. One hundred and twenty (120) structured questionnaires were administered to gather information from the farmers through an interview schedule. Majority of the livestock farmers in Mubi south (56.67%) Mubi north (63.33%), Madagali (53.33%) and Michika (80%) were males. Most of the respondents had secondary school certificates (40 to 50%) and Diploma certificates (23.33 to 36.70%). Greater proportion of the livestock farmers had family size of 5 to 10 people per family. Family labour accounted the highest (43.33 to 60%) types of labour used in managing the animals. Sizable population (53.33 to 63.33%) of the livestock farmers kept domestic animals as source of income. Livestock populations were observed to have been drastically reduced as a result of Boko Haram attacks. -

The Conflicting Linguistic and Ethnic Identities of the Fulani People of Ilorin

International Journal of Language and Linguistics Vol. 5, No. 1, March 2018 Language against Ethnicity: The Conflicting Linguistic and Ethnic Identities of the Fulani People of Ilorin Yeseera Omonike Oloso Kwara State University, Malete Nigeria Language against ethnicity the conflicting linguistic and ethnic identities of the Fulani people of Ilorin Ilorin’s status as a border community straddling Nigeria’s Northern and South-western regions where different languages and ethnicities co-exist makes identity construction complex. Existing literature largely posit an inseparable link between language and ethnic identity implying that language loss constitutes identity loss. This study investigates the relationship between linguistic and ethnic identities among the Fulani people of Ilorin with a view to evaluating the link. Revised Social and Ethnolinguistic Identity Theory was adopted. Structured interviews were conducted with 40 respondents while participant observation was employed. Linguistic identity was established in favour of the Yoruba Language contrariwise for the Yoruba ethnic identity. The majority of respondents (95.0%) identified Yoruba as their first language while respondents’ construction of their ethnic identities was largely influenced by their ancestral ethnicity. Seventy-five percent claimed sole Fulani ethnic identity; 5.0% claimed hybrid identity while 20.0% have become ethnic converts who claim either a civic or Yoruba identity. Keywords: Language shift, Allegiance, Ethnic converts, Revised ELIT. 1 Introduction This article examines the mosaic patterns of language and identity construction among the Fulani people of Ilorin. It shows how an overwhelming shift from Fulfulde, a minority language of Kwara State, did not translate into an equivalent shift of identity by its native speakers. -

•Chadic Classification Master

Paul Newman 2013 ò ê ž ŋ The Chadic Language Family: ɮ Classification and Name Index ɓ ō ƙ Electronic Publication © Paul Newman This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial License CC BY-NC Mega-Chad Research Network / Réseau Méga-Tchad http://lah.soas.ac.uk/projects/megachad/misc.html http://lah.soas.ac.uk/projects/megachad/divers.html The Chadic Language Family: Classification and Name Index Paul Newman I. CHADIC LANGUAGE CLASSIFICATION Chadic, which is a constituent member of the Afroasiatic phylum, is a family of approximately 170 languages spoken in Nigeria, Cameroon, Chad, and Niger. The classification presented here is based on the one published some twenty-five years ago in my Nominal and Verbal Plurality in Chadic, pp. 1–5 (Dordrecht: Foris Publications, 1990). This current paper contains corrections and updates reflecting the considerable amount of empirical research on Chadic languages done since that time. The structure of the classification is as follows. Within Chadic the first division is into four coordinate branches, indicated by Roman numerals: I. West Chadic Branch (W-C); II. Biu-Mandara Branch (B-M), also commonly referred to as Central Chadic; III. East Chadic Branch (E-C); and IV. Masa Branch (M-S). Below the branches are unnamed sub-branches, indicated by capital letters: A, B, C. At the next level are named groups, indicated by Arabic numerals: 1, 2.... With some, but not all, groups, subgroups are distinguished, these being indicated by lower case letters: a, b…. Thus Miya, for example, is classified as I.B.2.a, which is to say that it belongs to West Chadic (I), to the B sub-branch of West Chadic, to the Warji group (2), and to the (a) subgroup within that group, which consists of Warji, Diri, etc., whereas Daba, for example, is classified as II.A.7, that is, it belongs to Biu-Mandara (II), to the A sub-branch of Biu-Mandara, and within Biu-Mandara to the Daba group (7). -

Assessment of Dispute Resolution Structures and Hlp Issues in Borno and Adamawa States, North-East Nigeria

ASSESSMENT OF DISPUTE RESOLUTION STRUCTURES AND HLP ISSUES IN BORNO AND ADAMAWA STATES, NORTH-EAST NIGERIA March 2018 1 The Norwegian Refugee Council is an independent humanitarian organisation helping people forced to flee. Prinsensgate 2, 0152 Oslo, Norway Authors Majida Rasul and Simon Robins for the Norwegian Refugee Council, September 2017 Graphic design Vidar Glette and Sara Sundin, Ramboll Cover photo Credit NRC. Aerial view of the city of Maiduguri. Published March 2018. Queries should be directed to [email protected] The production team expresses their gratitude to the NRC staff who contributed to this report. This project was funded with UK aid from the UK government. The contents of the document are the sole responsibility of the Norwegian Refugee Council and can under no circumstances be regarded as reflecting the position or policies of the UK Government. AN ASSESSMENT OF DISPUTE RESOLUTION STRUCTURES AND HLP ISSUES IN BORNO AND ADAMAWA STATES 2 Contents Executive summary ..........................................................................................5 Methodology ....................................................................................................................................................................8 Recommendations ......................................................................................................................................................9 1. Introduction ...............................................................................................10 1.1 Purpose of -

An Atlas of Nigerian Languages

AN ATLAS OF NIGERIAN LANGUAGES 3rd. Edition Roger Blench Kay Williamson Educational Foundation 8, Guest Road, Cambridge CB1 2AL United Kingdom Voice/Answerphone 00-44-(0)1223-560687 Mobile 00-44-(0)7967-696804 E-mail [email protected] http://rogerblench.info/RBOP.htm Skype 2.0 identity: roger blench i Introduction The present electronic is a fully revised and amended edition of ‘An Index of Nigerian Languages’ by David Crozier and Roger Blench (1992), which replaced Keir Hansford, John Bendor-Samuel and Ron Stanford (1976), a pioneering attempt to synthesize what was known at the time about the languages of Nigeria and their classification. Definition of a Language The preparation of a listing of Nigerian languages inevitably begs the question of the definition of a language. The terms 'language' and 'dialect' have rather different meanings in informal speech from the more rigorous definitions that must be attempted by linguists. Dialect, in particular, is a somewhat pejorative term suggesting it is merely a local variant of a 'central' language. In linguistic terms, however, dialect is merely a regional, social or occupational variant of another speech-form. There is no presupposition about its importance or otherwise. Because of these problems, the more neutral term 'lect' is coming into increasing use to describe any type of distinctive speech-form. However, the Index inevitably must have head entries and this involves selecting some terms from the thousands of names recorded and using them to cover a particular linguistic nucleus. In general, the choice of a particular lect name as a head-entry should ideally be made solely on linguistic grounds.