September/October 2013 Volume 12, Number 5 Inside

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rudiments Mapping -- an Axiomatic Approach to Music Composition

Rudiments Mapping -- An Axiomatic Approach to Music Composition Lin Hsin Hsin Lin Hsin Hsin Concert Hall email: [email protected] these rule based tonal structures that have been derived? Unlike in medical sciences, does one need to Abstract decompose to compose, or one should disregard the past and break free? How many rules (Wallace Berry, Be it art, music, text, mathematics or 1987) should be retained or how much is desired and computer languages, when represented digitally or retained intentionally? If such retention is to be otherwise, generically, they are “formulated” continued, will it affect future musical compositions, expressions. The difference lies in their manifestation or dwelling on the past is déja vu and passé. This as an audio or visual entity. Thus, understanding the paper examines these issues based on the author’s rudiments of these art forms is pivotal to establishing perspective and approach to music and her knowledge their interconnectivities. As such, by identifying and and experiences drawn from the field of visual art. It characterizing the rudiments contained therein, by investigates her approach to composition, tools and studying their inter activities yield important techniques and method of delivery for multiple digital information for artists and composers alike, it offers art forms and hence their convergence. new perspectives for composing music or otherwise. Drawing from the author’s research and rich interdisciplinary experiences, this paper 2 The Rudiments of Art Forms conceptualizes, compares and offers the similarities and differences, it presents the demystification of the On close codicological examination of incongruences of these art forms. It spells out the individual primary sources of art, music, and text author’s approach to composing new music digitally: using the principle of identification and comparison deriving from, and extending the dynamism of of the attributes of these entities, it establishes the incorporating one art form into the other. -

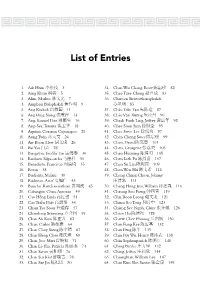

List of Entries

List of Entries 1. Aik Htun 3 34. Chan Wai Chang, Rose 82 2. Aing Khun 5 35. Chao Tzee Cheng 83 3. Alim, Markus 7 36. Charoen Siriwatthanaphakdi 4. Amphon Bulaphakdi 9 85 5. Ang Kiukok 11 37. Châu Traàn Taïo 87 6. Ang Peng Siong 14 38. Châu Vaên Xöông 90 7. Ang, Samuel Dee 16 39. Cheah Fook Ling, Jeffrey 92 8. Ang-See, Teresita 18 40. Chee Soon Juan 95 9. Aquino, Corazon Cojuangco 21 41. Chee Swee Lee 97 10. Aung Twin 24 42. Chen Chong Swee 99 11. Aw Boon Haw 26 43. Chen, David 101 12. Bai Yao 28 44. Chen, Georgette 103 13. Bangayan, Teofilo Tan 30 45. Chen Huiming 105 14. Banharn Silpa-archa 33 46. Chen Lieh Fu 107 15. Benedicto, Francisco 35 47. Chen Su Lan 109 16. Botan 38 48. Chen Wen Hsi 111 17. Budianta, Melani 40 49. Cheng Ching Chuan, Johnny 18. Budiman, Arief 43 113 19. Bunchu Rotchanasathian 45 50. Cheng Heng Jem, William 116 20. Cabangon Chua, Antonio 49 51. Cheong Soo Pieng 119 21. Cao Hoàng Laõnh 51 52. Chia Boon Leong 121 22. Cao Trieàu Phát 54 53. Chiam See Tong 123 23. Cham Tao Soon 57 54. Chiang See Ngoh, Claire 126 24. Chamlong Srimuang 59 55. Chien Ho 128 25. Chan Ah Kow 62 56. Chiew Chee Phoong 130 26. Chan, Carlos 64 57. Chin Fung Kee 132 27. Chan Choy Siong 67 58. Chin Peng 135 28. Chan Heng Chee 69 59. Chin Poy Wu, Henry 138 29. Chan, Jose Mari 71 60. -

Interaction of Colour & Light Book of Abstracts

Interaction of Colour & Light in the Arts and Sciences Midterm Meeting of the International Colour Association (AIC) 7–10 June 2011 Zurich, Switzerland Book of Abstracts Conference Proceedings on CD Editors: Verena M. Schindler, Stephan Cuber International Colour Association Internationale Vereinigung für die Farbe Association Internationale de la Couleur © 2011 pro/colore www.procolore.ch All rights reserved DISCLAIMER Matters of copyright for all images and text associated with the abstracts contained within the AIC 2011 Book of Abstracts are the responsibility of the authors. The AIC and pro/colore does not accept responsibility for any liabilities arising from the publication of any of the submissions. COPYRIGHT Reproduction of this document or parts thereof by any means whatsoever is prohibited without the written permission of pro/colore – Swiss Colour Association. All copies of the individual articles remain the intellectual property of the individual authors and/or their affiliated institutions. Please use the following format to cite material from the AIC 2011 Book of Abstracts: Author(s). “Title of abtract”. AIC 2011, Interaction of Colour & Light in the Arts and Sciences, Midterm Meeting of the International Color Association, Zurich, Switzerland, 7-10 June 2011: Book of Abstracts, edited by Verena M. Schindler and Stephan Cuber. Zurich: pro/colore, 2011, page number(s). This Book of Abstracts contains abstracts of the technical programme cited in the cover and title page of this volume. They reflect the author’s opinions and are published as presented. The full papers from the technical programme are published in the AIC 2011 Proceedings on CD. Editors: Verena M. -

Taiwanese Eyes on the Modern: Cold War Dance Diplomacy And

Taiwanese Eyes on the Modern: Cold War Dance Diplomacy and American Modern Dances in Taiwan, 1950–1980 Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Tsung-Hsin Lee, M.A. Graduate Program in Dance Studies The Ohio State University 2020 Dissertation Committee Hannah Kosstrin, Advisor Harmony Bench Danielle Fosler-Lussier Morgan Liu Copyrighted by Tsung-Hsin Lee 2020 2 Abstract This dissertation “Taiwanese Eyes on the Modern: Cold War Dance Diplomacy and American Modern Dances in Taiwan, 1950–1980” examines the transnational history of American modern dance between the United States and Taiwan during the Cold War era. From the 1950s to the 1980s, the Carmen De Lavallade-Alvin Ailey, José Limón, Paul Taylor, Martha Graham, and Alwin Nikolais dance companies toured to Taiwan under the auspices of the U.S. State Department. At the same time, Chinese American choreographers Al Chungliang Huang and Yen Lu Wong also visited Taiwan, teaching and presenting American modern dance. These visits served as diplomatic gestures between the members of the so-called Free World led by the U.S. Taiwanese audiences perceived American dance modernity through mixed interpretations under the Cold War rhetoric of freedom that the U.S. sold and disseminated through dance diplomacy. I explore the heterogeneous shaping forces from multiple engaging individuals and institutions that assemble this diplomatic history of dance, resulting in outcomes influencing dance histories of the U.S. and Taiwan for different ends. I argue that Taiwanese audiences interpreted American dance modernity as a means of embodiment to advocate for freedom and social change. -

Download Singapore Portraits Educators Guide For

Singapore Portraits Let The Photos Tell The Story Singapore Portraits is a tribute to some of Singapore’s most creative personalities. It features the works of and interviews with local artists which together tell the story of Singapore through their words and images. Besides the paintings and photographs, write-ups detailing the background of the artwork, social and historical contexts and artist biographies are also included. < for Primary School Students> Educators’ Guide Education and Community Outreach Division SG Portraits About The Exhibition Generations of Singapore artists and photographers have expressed themselves through art, telling stories of our nation, our history, people and their ways of lives. This exhibition looks at how Singapore has inspired art-making and what stories art tells about Singapore. Art in Singapore Drawn by the prospect of work in the region’s new European settlements, artists began to arrive here as early as the late 18th century. By the early 20th century, immigrant artists were forming art societies and the first school in Singapore, the Nanyang Academy of Fine Arts, was established in 1938. Among the most significant artists from the pioneering generation were Cheong Soo Pieng, Chen Chong Swee, Liu Kang, Chen Wen His, Georgette Chen and Lim Cheng Hoe. They were instrumental in establishing the Nanyang Style, the first local art style that emerged in the 1950s. Their work influenced younger generations of artists who followed in their footsteps to explore fresh ways of expressing local identity and local relevancy through their art. Take some time to share with students the importance of appreciating Art and the Arts that can help in their overall development. -

Brother Joseph Mcnally P

1 Design Education in Asia 2000- 2010 Exploring the impact of institutional ‘twinning’ on graphic design education in Singapore Simon Richards Z3437992 2 3 Although Singapore recently celebrated 50 years of graphic design, relatively little documentation exists about the history of graphic design in the island state. This research explores Singaporean design education institutes that adopted ‘twinning’ strategies with international design schools over the last 20 years and compares them with institutions that have retained a more individual and local profile. Seeking to explore this little-studied field, the research contributes to an emergent conversation about Singapore’s design history and how it has influenced the current state of the design industry in Singapore. The research documents and describes the growth resulting from a decade of investment in the creative fields in Singapore. It also establishes a pattern articulated via interviews and applied research involving local designers and design educators who were invited to take part in the research. The content of the interviews demonstrates strong views that reflect the growing importance of creativity and design in the local society. In considering the deliberate practice of Singaporean graphic design schools adopting twinning strategies with western universities, the research posits questions about whether Singapore is now able to confirm that such relationships have been beneficial as viable long-term strategies for the future of the local design industry. If so, the ramifications may have a significant impact not only in Singapore but also in major new education markets throughout Asia, such as the well-supported creative sectors within China and India. -

The Artistic Adventure of Two Bali Trips, 1952 and 2001

Wang Ruobing The Quest for a Regional Culture: The Artistic Adventure of Two Bali Trips, 1952 and 2001 Left to right: Liu Kang, Cheong Soo Pieng, Luo Ming, Ni Pollok, Adrien-Jean La Mayeur, Chen Chong Swee, Chen Wen Hsi, 1952. Courtesy of Liu Kang Family. iu Kang (1911–2004), Chen Wen Hsi (1906–1991), Cheong Soo Pieng (1917–83), and Chen Chong Swee (1910–1986) are four Limportant early artists of Singapore. They were born in China and emigrated to what was then called Malaya before the founding of the People’s Republic of China.1 In 1952, these four members of the Chinese diaspora went to Bali for a painting trip. Struck by the vibrant scenery and exoticism of Balinese culture, on their return they produced from their sketches a significant amount of artwork that portrayed the primitive and pastoral Bali in a modernist style, and a group exhibition entitled Pictures from Bali was held a year later at the British Council on Stamford Road in Singapore. This visit has been regarded as a watershed event in Singapore’s art history,2 signifying the birth of the Nanyang style through their processing of Balinese characteristics into a unique “local colour”—an aesthetic referring to a localized culture and identity within the Southeast Asian context. Their Bali experience had great significance, not only for their subsequent artistic development, both as individuals and as a group, but also for the stylistic development of Singaporean artists who succeeded them.3 Vol. 12 No. 5 77 Exhibition of Pictures from Bali, British Council, Singapore, 1953. -

OCA AR2013.Pdf

p. 4 Director’s Foreword p. 6 Statement of the Board p.12 International Support p. 102 Biennials and Major Solo Exhibitions p. 127 International Studio Programme p. 134 International Residencies Office for Contemporary Art Norway Annual Report 2013 145 p. International Visitor Programme p. 152 OCA Semesterplan p. 164 OCA’s Publication Series Verksted p. 167 Project: ‘On Négritude: A Series of Lectures on the Politics of Art Production in Africa’ p. 171 Project: ‘WORD! WORD? WORD! Office for Issa Samb and the Contemporary Art Undecipherable Form’ Norway p. 182 Project: ‘Fashion: the Fall of an Industry’ p. 198 Project: ‘Anthropocene Observatory: Empire of Calculus’ p. 204 Norway at the Venice Biennale p. 214 OCA in the Press p. 237 Key Figures 2013 p. 257 Organisation and the Board 3 Dear Friend, A Letter to You This is a Letter to You. I have only recently arrived In this regard the necessity to stimulate a reading and we may have not yet met. In fact, we are still and intervention into history in unforeseen ways in the about to, or just have, moment during which becomes vital, so as to nurture and nourish the cre- contours touch, when interiors start to seep and ative potential of the day. Such interventions must blend. We are in the now that ignites a new endeav- be multiple in nature, asymmetric in duration, and our, and anticipates fresh liaisons along the expanse worldly in spirit. Indeed, as practitioners in Norway of a nation and the lands beyond it. Together we repeatedly point to the malleability of how the past start to interweave our thoughts and actions. -

CENTRAL PAVILION, GIARDINI DELLA BIENNALE 29.08 — 8.12.2020 La Biennale Di Venezia La Biennale Di Venezia President Presents Roberto Cicutto

LE MUSE INQUIETE WHEN LA BIENNALE DI VENEZIA MEETS HISTORY CENTRAL PAVILION, GIARDINI DELLA BIENNALE 29.08 — 8.12.2020 La Biennale di Venezia La Biennale di Venezia President presents Roberto Cicutto Board The Disquieted Muses. Luigi Brugnaro Vicepresidente When La Biennale di Venezia Meets History Claudia Ferrazzi Luca Zaia Auditors’ Committee Jair Lorenco Presidente Stefania Bortoletti Anna Maria Como in collaboration with Director General Istituto Luce-Cinecittà e Rai Teche Andrea Del Mercato and with AAMOD-Fondazione Archivio Audiovisivo del Movimento Operaio e Democratico Archivio Centrale dello Stato Archivio Ugo Mulas Bianconero Archivio Cameraphoto Epoche Fondazione Modena Arti Visive Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna e Contemporanea IVESER Istituto Veneziano per la Storia della Resistenza e della Società Contemporanea LIMA Amsterdam Peggy Guggenheim Collection Tate Modern THE DISQUIETED MUSES… The title of the exhibition The Disquieted Muses. When La Biennale di Venezia Meets History does not just convey the content that visitors to the Central Pavilion in the Giardini della Biennale will encounter, but also a vision. Disquiet serves as a driving force behind research, which requires dialogue to verify its theories and needs history to absorb knowledge. This is what La Biennale does and will continue to do as it seeks to reinforce a methodology that creates even stronger bonds between its own disciplines. There are six Muses at the Biennale: Art, Architecture, Cinema, Theatre, Music and Dance, given a voice through the great events that fill Venice and the world every year. There are the places that serve as venues for all of La Biennale’s activities: the Giardini, the Arsenale, the Palazzo del Cinema and other cinemas on the Lido, the theatres, the city of Venice itself. -

ANSELM KIEFER Education Solo Exhibitions

ANSELM KIEFER 1945 Born in Donaueschingen, Germany Lives and works in France Education 1970 Staatliche Kunstakademie, Düsseldorf, Germany 1969 Staatliche Akademie der Bildenden Künste, Karlsruhe, Germany Solo exhibitions 2021 Field of the Cloth of Gold, Gagosian Le Bourget, France 2020 Permanent Public Commission, Panthéon, Paris Für Walther Von Der Vogelweide, Thaddaeus Ropac, Salzburg Villa Kast, Austria Opus Magnum, Franz Marc Museum, Kochel, Germany Superstrings, Runes, the Norns, Gordian Knot, White Cube, London 2019 Couvent de la Tourette, Lyon, France Books and Woodcuts, Foundation Jan Michalski, Montricher, Switzerland; Astrup Fearnley Museum, Oslo 2018 ARTISTS ROOMS: Anselm Kiefer, Herbert Art Gallery and Museum, West Midlands, UK Fugit Amor, Lia Rumma Gallery, Naples For Vicente Huidobro, White Cube, London Für Andrea Emo, Galerie Thaddeus Ropac, Paris Uraeus, Rockefeller Center, New York 2017 Provocations: Anselm Kiefer at the Met Breuer, Met Breuer, New York Anselm Kiefer, for Velimir Khlebnikov, The State Hermitage Museum, Saint Petersburg, Russia Transition from Cool to Warm, Gagosian, New York For Louis-Ferdinand Céline: Voyage au bout de la nuit, Copenhagen Contemporary, Denmark Kiefer Rodin, Rodin Museum, Paris; Barnes Foundation, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 2016 The Margulies Collection at the Warehouse, Miami Walhalla, White Cube, London The Woodcuts, Albertina Museum, Vienna Regeneration Series: Anselm Kiefer from the Hall Collection, NSU Art Museum, Fort Lauderdale, Florida 2015 Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris In the -

Curriculum Vitae

CURRICULUM VITAE BM Çağdaş Sanat Merkezi BM Contemporary Art Center BERAL MADRA BM CONTEMPORARY ART CENTER AKKAVAK SOK: 1/1 34365 NİŞANTAŞ-ISTANBUL TEL: 0090 212 2310 1023 FAX: 0090 212 292 68 65 E-MAIL:/[email protected] / [email protected] www.pluversum.blogspot.com; www.supremepolicy.blogspot.com Art Critic and Curator, Director of BM Contemporary Art Center * Born in Istanbul (1942), Graduate of German High School, Istanbul (1951-1961) The University of Istanbul, Faculty of Literature, Department of Archaelogy (1967). Free lance art critic and curator (since 1980). Married to photographer and multi-media artist Teoman Madra, has two children: Tulya Madra: www.mosantimetre.com; Yahya Mete Madra : Ass.Prof. Bosphorus University (2011-) Language: German and English. Founding Member of Foundation for Future Culture and Art; AICA Turkey: www.aicaturkey.com ; Anadolu Kültür AŞ and AICA Turkey, European Culture Association: www.europist.net; Founding member of The Association for Modern and Contemporary Art of the Arab world, Iran, and Turkey (AMCA) (2007): www.amcainternational.org Teaching Experience: Academy of Fine Arts (1980-82); Yıldız University Art and Design Faculty (Founder of Art Management Program and Lecturer (2000-2004); Yeditepe University Art Management Program (2005-2006) ; BM CAC independent seminars and workshops on contemporary art, media art and photography since 2000. Gallery BM (1984-1991) and BM Contemporary Art Center (since 1991) 1984-2010-Curated the solo- exhibitions of the following artists: Ahmet Öktem, -

Hans Haacke Biography

P A U L A C O O P E R G A L L E R Y Hans Haacke Biography 1936 Born Cologne, Germany 1956-60 Staatliche Werkakademie (State Art Academy), Kassel, Staatsexamen (equivalent of M.F.A.) 1960-61 Stanley William Hayter's Atelier 17, Paris 1961 Tyler School of Fine Arts, Temple University, Philadelphia 1962 Moves to New York 1963-65 Return to Cologne. Teaches at Pädagogische Hochschule, Kettwig, and other institutions 1966-67 Teaches at University of Washington, Seattle; Douglas College, Rutgers University, New Jersey; Philadelphia College of Art 1967 - 2002 Teaches at Cooper Union, New York (Professor of Art Emeritus) 1973 Guest Professorship, Hochschule für Bildende Künste, Hamburg 1979 Guest Professorship, Gesamthochschule, Essen 1994 Guest Professorship, Hochschule für Bildende Künste, Hamburg 1997 Regents Lecturer, University of California, Berkeley Lives in New York (since 1965) Awards 1960 Deutscher Akademischer Austauschdienst (DAAD) 1961 Fulbright Fellowship 1973 John Simon Guggenheim Foundation Fellowship 1978 National Endowment for the Arts 1991 College Art Association Distinguished Artist Award for Lifetime Achievement Deutscher Kritikerpreis for 1990 Honorary Doctorate in Fine Arts, Oberlin College 1993 Golden Lion (shared with Nam June Paik), Venice Biennale 1997 Kurt-Eisner-Foundation, Munich Honorary Doctorate Bauhaus-Universität Weimar 2001 Prize of Helmut-Kraft-Stiftung, Stuttgart 2002 College Art Association Distinguished Teaching of Art Award 2004 Peter-Weiss-Preis, Bochum 2008 Honorary Doctorate, San Francisco Art Institute