Some Patterns of Common Irregular Verbs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Animacy and Alienability: a Reconsideration of English

Running head: ANIMACY AND ALIENABILITY 1 Animacy and Alienability A Reconsideration of English Possession Jaimee Jones A Senior Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation in the Honors Program Liberty University Spring 2016 ANIMACY AND ALIENABILITY 2 Acceptance of Senior Honors Thesis This Senior Honors Thesis is accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation from the Honors Program of Liberty University. ______________________________ Jaeshil Kim, Ph.D. Thesis Chair ______________________________ Paul Müller, Ph.D. Committee Member ______________________________ Jeffrey Ritchey, Ph.D. Committee Member ______________________________ Brenda Ayres, Ph.D. Honors Director ______________________________ Date ANIMACY AND ALIENABILITY 3 Abstract Current scholarship on English possessive constructions, the s-genitive and the of- construction, largely ignores the possessive relationships inherent in certain English compound nouns. Scholars agree that, in general, an animate possessor predicts the s- genitive while an inanimate possessor predicts the of-construction. However, the current literature rarely discusses noun compounds, such as the table leg, which also express possessive relationships. However, pragmatically and syntactically, a compound cannot be considered as a true possessive construction. Thus, this paper will examine why some compounds still display possessive semantics epiphenomenally. The noun compounds that imply possession seem to exhibit relationships prototypical of inalienable possession such as body part, part whole, and spatial relationships. Additionally, the juxtaposition of the possessor and possessum in the compound construction is reminiscent of inalienable possession in other languages. Therefore, this paper proposes that inalienability, a phenomenon not thought to be relevant in English, actually imbues noun compounds whose components exhibit an inalienable relationship with possessive semantics. -

Learn Pronouns As Part of Speech for Bank & SSC Exams

Learn Pronouns as Part of Speech for Bank & SSC Exams - English Notes in PDF Are you preparing for Banking or SSC Exams? If you aim at making a career in the government sector & get a reputed job, it is very important to know the basics of English Language. To score maximum marks in this section with great accuracy, it is important for you to be prepared with the basic grammar & vocabulary. Here we are with a detailed explanatory article on Pronouns as Part of Speech with relevant examples. So, read the article carefully & then take our Online Mock Tests to check your level of preparation. Before moving ahead with Pronouns, let’s have a look at what are parts of speech in brief: Parts of Speech Parts of speech are the basic categories of words according to their function in a sentence. It is a category to which a word is assigned in accordance with its syntactic functions. English has eight main parts of speech, namely, Nouns, Pronouns, Adjectives, Verbs, Adverbs, Prepositions, Conjunctions & Interjections. In grammar, the parts of speech, also called lexical categories, grammatical categories or word classes is a linguistic category of words. Pronouns as Part of Speech 1 | Pronouns as part of speech are the words which are used in place of nouns like people, places, or things. They are used to avoid sounding unnatural by reusing the same noun in a sentence multiple times. In the sentence Maya saw Sanjay, and she waved at him, the pronouns she and him take the place of Maya and Sanjay, respectively. -

The Function of Phrasal Verbs and Their Lexical Counterparts in Technical Manuals

Portland State University PDXScholar Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses 1991 The function of phrasal verbs and their lexical counterparts in technical manuals Brock Brady Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/open_access_etds Part of the Applied Linguistics Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Brady, Brock, "The function of phrasal verbs and their lexical counterparts in technical manuals" (1991). Dissertations and Theses. Paper 4181. https://doi.org/10.15760/etd.6065 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Brock Brady for the Master of Arts in Teaching English to Speakers of Other Languages (lESOL) presented March 29th, 1991. Title: The Function of Phrasal Verbs and their Lexical Counterparts in Technical Manuals APPROVED BY THE MEMBERS OF THE THESIS COMMITTEE: { e.!I :flette S. DeCarrico, Chair Marjorie Terdal Thomas Dieterich Sister Rita Rose Vistica This study investigates the use of phrasal verbs and their lexical counterparts (i.e. nouns with a lexical structure and meaning similar to corresponding phrasal verbs) in technical manuals from three perspectives: (1) that such two-word items might be more frequent in technical writing than in general texts; (2) that these two-word items might have particular functions in technical writing; and that (3) 2 frequencies of these items might vary according to the presumed expertise of the text's audience. -

Possessive Constructions in Modern Low Saxon

POSSESSIVE CONSTRUCTIONS IN MODERN LOW SAXON a thesis submitted to the department of linguistics of stanford university in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of master of arts Jan Strunk June 2004 °c Copyright by Jan Strunk 2004 All Rights Reserved ii I certify that I have read this thesis and that, in my opinion, it is fully adequate in scope and quality as a thesis for the degree of Master of Arts. Joan Bresnan (Principal Adviser) I certify that I have read this thesis and that, in my opinion, it is fully adequate in scope and quality as a thesis for the degree of Master of Arts. Tom Wasow I certify that I have read this thesis and that, in my opinion, it is fully adequate in scope and quality as a thesis for the degree of Master of Arts. Dan Jurafsky iii iv Abstract This thesis is a study of nominal possessive constructions in modern Low Saxon, a West Germanic language which is closely related to Dutch, Frisian, and German. After identifying the possessive constructions in current use in modern Low Saxon, I give a formal syntactic analysis of the four most common possessive constructions within the framework of Lexical Functional Grammar in the ¯rst part of this thesis. The four constructions that I will analyze in detail include a pronominal possessive construction with a possessive pronoun used as a determiner of the head noun, another prenominal construction that resembles the English s-possessive, a linker construction in which a possessive pronoun occurs as a possessive marker in between a prenominal possessor phrase and the head noun, and a postnominal construction that involves the preposition van/von/vun and is largely parallel to the English of -possessive. -

The Use of Demonstrative Pronoun and Demonstrative Determiner This in Upper-Level Student Writing: a Case Study

English Language Teaching; Vol. 8, No. 5; 2015 ISSN 1916-4742 E-ISSN 1916-4750 Published by Canadian Center of Science and Education The Use of Demonstrative Pronoun and Demonstrative Determiner this in Upper-Level Student Writing: A Case Study Katharina Rustipa1 1 Faculty of Language and Cultural Studies, Stikubank University (UNISBANK) Semarang, Indonesia Correspondence: Katharina Rustipa, UNISBANK Semarang, Jl. Tri Lomba Juang No.1 Semarang 50241, Indonesia. Tel: 622-4831-1668. E-mail: [email protected] Received: January 20, 2015 Accepted: February 26, 2015 Online Published: April 23, 2015 doi:10.5539/elt.v8n5p158 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.5539/elt.v8n5p158 Abstract Demonstrative this is worthy to investigate because of the role of this as a common cohesive device in academic writing. This study attempted to find out the variables underlying the realization of demonstrative this in graduate-student writing of Semarang State University, Indonesia. The data of the study were collected by asking three groups of students (first semester, second semester, third semester students) to write an essay. The collected data were analyzed by identifying, classifying, calculating, and interpreting. Interviewing to several students was also done to find out the reasons underlying the use of attended and unattended this. Comparing the research results to those of the Michigan Corpus of Upper-level Student Paper (MICUSP) as proficient graduate-student writing was done in order to know the position of graduate-student writing of Semarang State University in reference to MICUSP. The conclusion of the research results is that most occurrences of demonstrative this are attended and these occurrences are stable across levels, similar to those in MICUSP. -

Understanding English Non-Count Nouns and Indefinite Articles

Understanding English non-count nouns and indefinite articles Takehiro Tsuchida Digital Hollywood University December 20, 2010 Introduction English nouns are said to be categorised into several groups according to certain criteria. Among such classifications is the division of count nouns and non-count nouns. While count nouns have such features as plural forms and ability to take the indefinite article a/an, non-count nouns are generally considered to be simply the opposite. The actual usage of nouns is, however, not so straightforward. Nouns which are usually regarded as uncountable sometimes take the indefinite article and it seems fairly difficult for even native speakers of English to expound the mechanism working in such cases. In particular, it seems to be fairly peculiar that the noun phrase (NP) whose head is the abstract „non-count‟ noun knowledge often takes the indefinite article a/an and makes such phrase as a good knowledge of Greek. The aim of this paper is to find out reasonable answers to the question of why these phrases occur in English grammar and thereby to help native speakers/teachers of English and non-native teachers alike to better instruct their students in 1 the complexity and profundity of English count/non-count dichotomy and actual usage of indefinite articles. This report will first examine the essential qualities of non-count nouns and indefinite articles by reviewing linguistic literature. Then, I shall conduct some research using the British National Corpus (BNC), focusing on statistical and semantic analyses, before finally certain conclusions based on both theoretical and actual observations are drawn. -

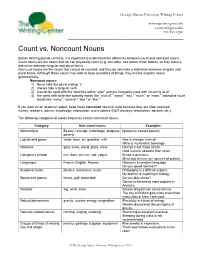

Count Vs Noncount Nouns

George Mason University Writing Center writingcenter.gmu.edu The [email protected] Writing Center 703.993.1200 Count vs. Noncount Nouns Before forming plurals correctly, it is important to understand the difference between count and noncount nouns. Count nouns are the nouns that we can physically count (e.g. one table, two tables, three tables), so they make a distinction between singular and plural forms. Noncount nouns are the nouns that cannot be counted, and they do not make a distinction between singular and plural forms. Although these nouns may refer to large quantities of things, they act like singular nouns grammatically. Noncount nouns: 1) Never take the plural ending “s” 2) Always take a singular verb 3) Cannot be used with the indefinite article “a/an” and are frequently used with no article at all 4) Are used with collective quantity words like “a lot of,” “some,” “any,” “much,” or “more,” instead of count words like “many,” “several,” “two,” or “few.” If you work on an academic paper, keep these noncount nouns in mind because they are often misused: money, research, advice, knowledge, information, and evidence (NOT moneys, researches, advices, etc.). The following categories of words frequently contain noncount nouns: Category Non-count nouns Examples Abstractions Beauty, revenge, knowledge, progress, Ignorance causes poverty. poverty Liquids and gases water, beer, air, gasoline, milk Gas is cheaper than oil. Wine is my favorite beverage. Materials gold, silver, wood, glass, sand He had a will made of iron. Gold is more valuable than silver. Categories of food rice, flour, cheese, salt, yogurt Bread is delicious. -

Greek and Latin Roots, Prefixes, and Suffixes

GREEK AND LATIN ROOTS, PREFIXES, AND SUFFIXES This is a resource pack that I put together for myself to teach roots, prefixes, and suffixes as part of a separate vocabulary class (short weekly sessions). It is a combination of helpful resources that I have found on the web as well as some tips of my own (such as the simple lesson plan). Lesson Plan Ideas ........................................................................................................... 3 Simple Lesson Plan for Word Study: ........................................................................... 3 Lesson Plan Idea 2 ...................................................................................................... 3 Background Information .................................................................................................. 5 Why Study Word Roots, Prefixes, and Suffixes? ......................................................... 6 Latin and Greek Word Elements .............................................................................. 6 Latin Roots, Prefixes, and Suffixes .......................................................................... 6 Root, Prefix, and Suffix Lists ........................................................................................... 8 List 1: MEGA root list ................................................................................................... 9 List 2: Roots, Prefixes, and Suffixes .......................................................................... 32 List 3: Prefix List ...................................................................................................... -

Verbal Agreement with Collective Nominal Constructions: Syntactic and Semantic Determinants

ATLANTIS Journal of the Spanish Association of Anglo-American Studies 39.1 (June 2017): 33-54 issn 0210-6124 | e-issn 1989-6840 Verbal Agreement with Collective Nominal Constructions: Syntactic and Semantic Determinants Yolanda Fernández-Pena Universidade de Vigo [email protected] This corpus-based study investigates the patterns of verbal agreement of twenty-three singular collective nouns which take of-dependents (e.g., a group of boys, a set of points). The main goal is to explore the influence exerted by theof -PP on verb number. To this end, syntactic factors, such as the plural morphology of the oblique noun (i.e., the noun in the of- PP) and syntactic distance, as well as semantic issues, such as the animacy or humanness of the oblique noun within the of-PP, were analysed. The data show the strongly conditioning effect of plural of-dependents on the number of the verb: they favour a significant proportion of plural verbal forms. This preference for plural verbal patterns, however, diminishes considerably with increasing syntactic distance when the of-PP contains a non-overtly- marked plural noun such as people. The results for the semantic issues explored here indicate that animacy and humanness are also relevant factors as regards the high rate of plural agreement observed in these constructions. Keywords: agreement; collective; of-PP; distance; animacy; corpus . Concordancia verbal con construcciones nominales colectivas: sintaxis y semántica como factores determinantes Este estudio de corpus investiga los patrones de concordancia verbal de veintitrés nombres colectivos singulares que toman complementos seleccionados por la preposición of, como en los ejemplos a group of boys, a set of points. -

The Morphology of Modern Western Abenaki

The Morphology of Modern Western Abenaki Jesse Beach ‘04 Honors Thesis Dartmouth College Program of Linguistics & Cognitive Science Primary Advisor: Prof. David Peterson Secondary Advisor: Prof. Lindsay Whaley May 17, 2004 Acknowledgements This project has commanded a considerable amount of my attention and time over the past year. The research has lead me not only into Algonquian linguistics, but has also introduced me to the world of Native American cultures. The history of the Abenaki people fascinated me as much as their language. I must extnd my fullest appreciate to my advisor David Peterson, who time and again proposed valuable reference suggestions and paths of analysis. The encouragement he offered was indispensable during the research and writing stages of this thesis. He also went meticulously through the initial drafts of this document offering poignant comments on content as well as style. My appreciation also goes to my secondary advisor Lindsay Whaley whose door is always open for a quick chat. His suggestions helped me broaden the focus of my research. Although I was ultimately unable to arrange the field research component of this thesis, the generosity of the Dean of Faculty’s Office and the Richter Memorial Trust Grant that I received from them assisted me in gaining a richer understanding of the current status of the Abenaki language. With the help of this grant, I was able to travel to Odanak, Quebec to meet the remaining speakers of Abenaki. From these conversations I was able to locate additional materials that aided me tremendously in my analysis. Many individuals have offered me assistance in one form or another throughout the unfolding of my research. -

The Definite Determiner in Early Middle English

43 The defi nite determiner in Early Middle English: What happened with þe? Cynthia L. Allen Australian National University Abstract This paper offers new data bearing on the question of when English developed a defi nite article, distinct from the distal demonstrative. It focuses primarily on one criterion that has been used in dating this development, namely the inability of þe (Modern English the, the refl ex of the demonstrative se) to be used as a pronoun. I argue that this criterion is not a satisfactory one and propose a treatment of þe as a form which could occupy either the head D of DP or the specifi er of DP. This is an approach consistent with Crisma’s (2011) position that a defi nite article emerged within the Old English (OE) period. I offer a new piece of evidence supporting Crisma’s demonstration of a difference between OE poetry and the prose of the ninth century and later. 1. Introduction: dating the defi nite article A long-standing problem in historical English syntax is dating the emergence of the defi nite article. A major diffi culty here, noted by Johanna Wood (2003) and others, is defi ning exactly what we mean by an ‘article.’ Millar (2000:304, note 11) comments that we might say that Modern English does not have a ‘true’ article, but only a ‘weakly demonstrative defi nite determiner’ on Himmelmann’s (1997) proposed path of development for defi nite articles. However, no one can doubt that English has moved along this path from a demonstrative determiner to something that has become more purely grammatical, with loss of deictic properties. -

A Minimalist Study of Complex Verb Formation: Cross-Linguistic Paerns and Variation

A Minimalist Study of Complex Verb Formation: Cross-linguistic Paerns and Variation Chenchen Julio Song, [email protected] PhD First Year Report, June 2016 Abstract is report investigates the cross-linguistic paerns and structural variation in com- plex verbs within a Minimalist and Distributed Morphology framework. Based on data from English, German, Hungarian, Chinese, and Japanese, three general mechanisms are proposed for complex verb formation, including Akt-licensing, “two-peaked” adjunction, and trans-workspace recategorization. e interaction of these mechanisms yields three levels of complex verb formation, i.e. Root level, verbalizer level, and beyond verbalizer level. In particular, the verbalizer (together with its Akt extension) is identified as the boundary between the word-internal and word-external domains of complex verbs. With these techniques, a unified analysis for the cohesion level, separability, component cate- gory, and semantic nature of complex verbs is tentatively presented. 1 Introduction1 Complex verbs may be complex in form or meaning (or both). For example, break (an Accom- plishment verb) is simple in form but complex in meaning (with two subevents), understand (a Stative verb) is complex in form but simple in meaning, and get up is complex in both form and meaning. is report is primarily based on formal complexity2 but tries to fit meaning into the picture as well. Complex verbs are cross-linguistically common. e above-mentioned understand and get up represent just two types: prefixed verb and phrasal verb. ere are still other types of complex verb, such as compound verb (e.g. stir-fry). ese are just descriptive terms, which I use for expository convenience.