Commentary on First Peter After All

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 Peter 3:15–22, “God in Your Hearts” 5/17/20, Sixth Sunday of Easter Pastor Alex Amiot

1 Peter 3:15–22, “God in Your Hearts” 5/17/20, Sixth Sunday of Easter Pastor Alex Amiot 1 Peter 3:15–22 (NKJV) 15 But sanctify the Lord God in your hearts, and always be ready to give a defense to 16 everyone who asks you a reason for the hope that is in you, with meekness and fear; having a good conscience, that when they defame you as evildoers, those who revile your good conduct in 17 Christ may be ashamed. For it is better, if it is the will of God, to suffer for doing good than for doing evil. 18 For Christ also suffered once for sins, the just for the unjust, that He might bring us to 19 God, being put to death in the flesh but made alive by the Spirit, by whom also He went and 20 preached to the spirits in prison, who formerly were disobedient, when once the Divine longsuffering waited in the days of Noah, while the ark was being prepared, in which a few, that 21 is, eight souls, were saved through water. There is also an antitype which now saves us—baptism (not the removal of the filth of the flesh, but the answer of a good conscience 22 toward God), through the resurrection of Jesus Christ, who has gone into heaven and is at the right hand of God, angels and authorities and powers having been made subject to Him. When the Apostle Peter writes in 1 Peter 3:15, “Sanctify the Lord God in your hearts,” he is making an assumption about his readers. -

1 Peter 3:19-22

Dr. Terren Dames 1 Peter 3:19-22 19. In which also He went and made proclamation to the spirits now in prison, There are four main interpretations that have been proposed for this verse. Luther wrote: “A wonderful text is this, and a more obscure passage perhaps than any other in the New Testament, so that I do not know for a certainty just what Peter means.” First, Augustine, and many throughout church history, understood the text to refer to Christ’s preaching ________________ to those who lived while Noah was building the ark. According to this view, Christ was not __________________ but spoke by means of the Holy Spirit through Noah. The spirits are not __________________but refer to those who were snared in sin during Noah’s day. If this view is correct, any notion of Christ descending into hell is excluded. Second, some have understood Peter as referring to Old Testament ______________ and were liberated by Christ between his death and resurrection. Third, some believe Peter here referred to the descent of Christ’s ______________________ between His death and resurrection to offer people who lived before the Flood a _________ chance for _______________. However, this interpretation has no scriptural support. Most of those who adopt such an interpretation infer from this that God will offer a _______________ to all those _____________, especially to those who never heard the gospel. If salvation was offered to the wicked generation of Noah, surely it will also be extended to all sinners separated from God. (Schreiner). Dr. Terren Dames Fourth, the majority view among scholars today is that the text describes Christ’s ______________________ and ___________ over the ___________. -

“A Holy and Happy Marriage” (1 Peter 3:1–7)

“A Holy and Happy Marriage” (1 Peter 3:1–7) Abraham Lincoln once said, “Love is blind, but marriage is a real eye-opener.” 1 Abe certainly knew what he was talking about, didn’t he? One of the primary reasons that marriage is such an eye-opener is because men and women enter marriage with very different expectations. To summarize: A woman marries a man expecting he will change, but he doesn’t. A man marries a woman expecting that she won’t change and she does. Howard Hendricks likes to say people get married with a picture in their minds of a perfect marriage. Then after a few trials, they discover they aren’t married to a perfect picture, but an imperfect person. When this realization occurs, they will either tear up the picture or they will tear up the person. 2 One of the great needs of every marriage is to tear up our picture of the perfect spouse and work toward becoming the perfect spouse ourselves. This will require an enormous amount of time, energy, and effort. But the reward of a holy and happy marriage is one of the greatest rewards in all of life. So, how can you have this kind of marriage? Follow God’s directions. When you come down with a cold, you take a cold medication. Before doing so you read the directions. If you are healthy, you take vitamins. Again, before using any supplements, it is critical to read the directions. This is common sense! So, why do so many Christians with sick or healthy marriages frequently neglect reading the directions? Perhaps if we were more attentive to the instructions of the Designer we would find that marriages work much better. -

Ethical and Hermeneutical Considerations in 1 Peter 3:1–6 and Its Context JEANNINE K

Word & World Volume 24, Number 4 Fall 2004 Silent Wives, Verbal Believers: Ethical and Hermeneutical Considerations in 1 Peter 3:1–6 and Its Context JEANNINE K. BROWN irst Peter’s exhortations to Christian wives (1 Pet 3:1–6) and its call to Christian living for all believers (3:14–16) exhibit significant linguistic repetition. Does the similarity of terminology indicate a similarity of values? In this essay, I con- clude that, while most of the mirrored language between these passages conveys a common Christian ethic, some repeated terminology does in fact highlight differ- ing ethics. I will focus my attention on one such example. The ethical tension be- tween the silent witness exhorted for wives with their unbelieving husbands (3:1) will be examined in relationship to the command for believers to be ready with a verbal defense of their Christian hope (3:15). Following this, I will explore herme- neutical considerations for understanding this ethical tension. VERBAL SIMILARITIES BETWEEN 1PETER 3:1–6 AND 3:14–16 First Peter 3:1–6 is part of the household code of 1 Peter (2:11–3:12). As the part of the household code addressed to wives, 3:1–6 follows the initial exhortation Wives are to be silent witnesses; believers (including women) are to be verbal witnesses. With this tension, 1 Peter invites us to consider the complex task of the Christian community as it engages its social environment in challenge and testi- mony, then and now. Copyright © 2004 by Word & World, Luther Seminary, Saint Paul, Minnesota. All rights reserved. -

1 1 Peter 5:10-11 “The Devil Sure Is Busy.” This Is How Christians Often Respond When Bad Things Happen. It May Be a Trial

DIVINE ASSURANCE FOR CHRISTIAN SUFFERING 1 Peter 5:10-11 “The devil sure is busy.” This is how Christians often respond when bad things happen. It may be a trial we are undergoing. Or it can be a trial someone else is going through. But when something happens that is unpleasant, unending, or unexplainable, we often respond by saying, “The devil sure is busy.” It’s one of the things church folk say. I want to take issue with that statement. But I don’t object to this statement because it is true. The devil is busy. Ephesians 6:10-11 says, “Finally, be strong in the Lord and in the strength of his might. Put on the whole armor of God, that you may be able to stand against the schemes of the devil.” The devil is so busy that you need the whole armor of God to stand your ground against his evil schemes. That’s the truth. But it is not the whole truth. I submit that the devil is not the only one who is busy when bad things happen. God is also at work. Romans 8:28 says, “And we know that for those who love God all things work together for good, for those who are called according to his purpose.” Satan is busy at work against you. But God is at work on your behalf. You may not find “Under Construction” signs hanging around. You may not see the tracks of heavy machinery. You may not hear the sound of heavenly jackhammers in the distance. -

Fact Sheet for “The Coming Glory” 1 Peter 5:1-14 Pastor Bob Singer 06/26/2016

Fact Sheet for “The Coming Glory” 1 Peter 5:1-14 Pastor Bob Singer 06/26/2016 Today we come to the closing chapter of Peter’s first letter. In this chapter we will find both important theology and great application. Remember that Peter’s readers were experiencing persecution for their faith. His letter was sent to encourage them. ESV 1 ¶ So I exhort the elders among you, as a fellow elder and a witness of the sufferings of Christ, as well as a partaker in the glory that is going to be revealed: 2 shepherd the flock of God that is among you, exercising oversight, (-) not under compulsion, (+) but willingly, as God would have you; (-) not for shameful gain, (+) but eagerly; 3 (-) not domineering over those in your charge, (+) but being examples to the flock. 4 And when the chief Shepherd appears, you will receive the unfading crown of glory. Notice Peter’s mention of Christ’s sufferings and Peter’s own hope in the glory that is going to be revealed. He identifies with their suffering. Notice also that he identifies himself with their elders (“fellow elder”). His next words come from someone who can identify with them. Theology… These verses are some of the most critical in the NT in understanding church leadership. They were not only addressed to those whom our culture identifies as the “pastors”. You need to think biblically and not with current culture here. The following are a few observations. 1. These elders were the leaders of the church. 2. There was more than one. -

Insights on 1 Peter: Hope Again: When Life Hurts and Dreams Fade J Hope Beyond Failure: the Broken Man Behind the Book I 1 Peter

Insights on 1 Peter: Hope Again: When Life Hurts and Dreams Fade j Hope Beyond Failure: The Broken Man Behind the Book i 1 Peter The Heart of the Matter Without a doubt, Peter is the best known among Jesus’s original band of disciples. Tools for Bold, brash, impetuous, impulsive Peter; quick to speak, strongly opinionated, well- Digging Deeper meaning, and fiercely loyal . yet altogether human and given to emotional extremes. We cannot help but smile at him, especially as we see ourselves mirrored in his actions and words. Let’s get better acquainted with the man himself and the first letter he wrote. In doing so, we shall not only become more familiar with him; we will learn the overall theme of the letter he wrote to the Christians who were scattered and living as aliens in a hostile and hateful world. Insights on 1 Peter Discovering the Way Hope Again: When Life 1. Brief Sketch of Peter’s Life Hurts and Dreams Fade Peter has a rich history recorded alongside Jesus in the Gospels. From his call to follow by Charles R. Swindoll Christ and his role among the apostles to his devastating denial and eventual leadership CD Series in the church, Peter revealed a human face among the first followers of our Lord. 2. General Survey of Peter’s Letter Hope Again: When Life Whenever we approach a letter, it’s helpful to keep several questions in mind: who was Hurts and Dreams Fade Peter writing to? What’s the theme of Peter’s letter? And for what purpose did Peter pen by Insight for Living this epistle? workbook Swindoll’s New Testament Insights: Insights on James, 1 & 2 Peter Starting Your Journey by Charles R. -

An Exposition of 1 Peter 5:1-4

Bibliotheca Sacra 139 (1982) 330-341. Copyright © 1982 by Dallas Theological Seminary. Cited with permission. Selected Studies from 1 Peter Part 4: Counsel for Christ's Under- Shepherds: An Exposition of 1 Peter 5:1-4 D. Edmond Hiebert Therefore, I exhort the elders among you, as your fellow-elder and witness of the sufferings of Christ, and a partaker also of the glory that is to be revealed, shepherd the flock of God among you, not under compulsion, but voluntarily, according to the will of God: and not for sordid gain, but with eagerness; nor yet as lording it over those allotted to your charge, but proving to be examples to the flock. And when the Chief Shepherd appears. you will receive the unfading crown of glory (1 Pet. 5:1-4, NASB). In these four verses Peter offers loving counsel to the leaders of the afflicted believers living in five Roman provinces in what is today called Asia Minor. They constitute the first section of the concluding paragraph (5:1-11) of this practical epistle. The opening "Therefore" (ou#n) indicates a logical thought connection with what has gone before. This particle is omit- ted in the Textus Receptus, perhaps because this concluding paragraph of the epistle proper does not seem to be an obvious deduction from what has just been said, as "therefore" seem- ingly suggests. If it is omitted, 5:1-11 may be viewed as an appropriate summary of the author's ethical appeals to his readers. But modern textual editors agree in accepting it as the original reading.1 Then, in keeping with the inferential force of the particle, it is generally viewed as constituting, in effect, an expansion on "doing what is right" (e]n a]gaqopoii<%), the concluding words of the preceding paragraph (4:19). -

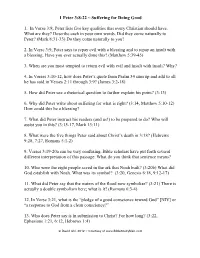

1 Peter 3:8-22 ~ Suffering for Doing Good

1 Peter 3:8-22 ~ Suffering for Doing Good 1. In Verse 3:8, Peter lists five key qualities that every Christian should have. What are they? Describe each in your own words. Did they come naturally to Peter? (Mark 8:31-33) Do they come naturally to you? 2. In Verse 3:9, Peter says to repay evil with a blessing and to repay an insult with a blessing. Have you ever actually done this? (Matthew 5:39-45) 3. When are you most tempted to return evil with evil and insult with insult? Why? 4. In Verses 3:10-12, how does Peter’s quote from Psalm 34 sum up and add to all he has said in Verses 2:11 through 3:9? (James 3:2-18) 5. How did Peter use a rhetorical question to further explain his point? (3:13) 6. Why did Peter write about suffering for what is right? (3:14, Matthew 5:10-12) How could this be a blessing? 7. What did Peter instruct his readers (and us!) to be prepared to do? Who will assist you in this? (3:15-17, Mark 13:11) 8. What were the five things Peter said about Christ’s death in 3:18? (Hebrews 9:28, 7:27, Romans 5:1-2) 9. Verses 3:19-20a can be very confusing. Bible scholars have put forth several different interpretation of this passage. What do you think that sentence means? 10. Who were the eight people saved in the ark that Noah built? (3:20b) What did God establish with Noah. -

1 Peter 3:19-21 Has Confused Many. Not The

1 Peter 3:19-21 has confused many. Not the least of which was Martin Luther, who said: “A wonderful text is this, and a more obscure passage perhaps than any other in the New Testament, so that I do not know for certainty what Peter means.” The main point is clarified by and culminates in verse 22: “[Jesus] has gone into heaven and is at the right hand of God, with angels, authorities, and powers having been subjected to him.” So while the precise details may be confusing, the primary declaration of this text is not confusing; it clearly states Jesus, the one who suffered as our all-sufficient Savior is now resurrected and exalted as the all-supreme Lord. Those who trust in Christ have no need to fear that suffering will have the last word. We are like Noah – we are small minority in a hostile world, but we can be bold in our witness and confident that our future is secure. What about the reference to baptism? Well, the water of baptism is like the waters of judgment, the flood waters, in Noah’s day – as we are immersed into the water we are reminded that we deserve death for our sins, just like those who died in the flood; and coming up from the water reminds we are kept safe by the ark of Christ and have risen to walk in newness of life. Peter is reminding us that in our suffering Jesus still rules and reigns; by his death and resurrection Jesus has triumphed over sin, Satan, and death. -

QUESTION and ANSWER 12/2/07 PM 1. When Jesus Was Dead For

QUESTION AND ANSWER 12/2/07 PM 1. When Jesus was dead for 3 days was He in Hell? 1 Peter 3:18-20a For Christ also died for sins once for all, the just for the unjust, so that He might bring us to God, having been put to death in the flesh, but made alive in the spirit; 19 in which also He went and made proclamation to the spirits now in prison, 20 who once were disobedient, when the patience of God kept waiting in the days of Noah, during the construction of the ark People have interpreted this passage several ways. The three most common are: 1. Christ descended into Hades between His death and resurrection to offer certain people a second chance at salvation. Proclamation- kerusso not euagglizo- to heard, not to preach the gospel Notice that this only refers to those who were alive in the days of Noah. But we have no other scriptural support for this. 2. Christ simply announced of His victory over sin to those in Hades, without offering them a second chance. Some take this proclamation to be to people that died in the flood. Others take it to refer to fallen angels from the time of Noah who are now imprisoned. Cf 2 Peter 2:4-5 3. Christ’s pre-incarnate spirit preached through Noah to these people before the flood. Now they are spirits in prison awaiting the final judgment. We see this idea expressed in another situation in Nehemiah 9:30 Nehemiah 9:30 "However, You bore with them for many years, And admonished them by Your Spirit through Your prophets, Yet they would not give ear. -

NB 08 Transcript

Naked Bible Podcast Episode 8: Baptism and Problem Passages: 1 Peter 3: 14-22 Naked Bible Podcast Transcript Episode 8 Baptism and Problem Passages: 1 Peter 3:14-22 Recorded in 2012 Teacher: Dr. Michael S. Heiser (MH) 1 Peter 3:14-22 is an odd, controversial passage since it amalgamates, baptism, salvation, Noah, the ark, and Jesus’ descent to preach to spirits in the Underworld. The key to understanding the passage is to recognize that Peter embraces the worldview of non-canonical Jewish literature like 1 Enoch and seems an analogy between the events of Genesis 6-8, salvation, and baptism. Transcript Welcome once again to the Naked Bible Podcast. The last podcast episode ended my summary of the problems with the way baptism gets talked about any my solutions to those problems. Now I want to take some time in the next few episodes to go through some difficult passages relating to baptism. In today's episode we'll tackle 1 Peter 3:14-22. So I want to read that to you now. 14 But even if you should suffer for righteousness' sake, you will be blessed. Have no fear of them, nor be troubled,15 but in your hearts honor Christ the Lord as holy, always being prepared to make a defense to anyone who asks you for a reason for the hope that is in you; yet do it with gentleness and respect, 16 having a good conscience, so that, when you are slandered, those who revile your good behavior in Christ may be put to shame.17 For it is better to suffer for doing good, if that should be God's will, than for doing evil.