The Book in Britain

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Discovery of a Watermark on the St Cuthbert Gospel Using Colour Space Analysis

The Discovery of a Watermark on the St Cuthbert Gospel using Colour Space Analysis Christina Duffy 1. Introduction Watermarks since their introduction in the thirteenth century have been used as a method of establishing the provenance and origin of paper, identifying mill trademarks and locations, and determining the sizes and intended functions of papers. Watermarks are designs such as a name, initials, or a decorative motif impressed on paper in a similar way to chain and laid lines.1 A watermark design was incorporated by manipulating wire into a recognizable shape and affixing it to the mould. The thickness of the paper is reduced over regions of wire which results in the familiar appearance of watermarks, chain lines, and laid lines when paper is held up to the light. Chain and laid lines are important even if they obscure the watermark design as their relative positions can aid in determining the orientation of the paper when the pages were laid out for printing. Imaging of watermarks has been problematic for curators and scholars with partial marks often found in non-adjacent gutters owing to the ordering and cutting of the folios. Techniques such as tracing, transmitted light and the Dylux method2 have been used in the past. More sophisticated methods such as beta radiation, IR imaging and thermography have improved results, but are still highly dependent on the material and only successful in certain cases. Best results are usually found when the watermarked folio can be accessed from both sides to allow light to pass through from the back, and the image to be photographically captured from the front. -

Umbc Review Journal of Undergraduate Research U M B C

UMBC2014 UMBC REVIEW JOURNAL OF UNDERGRADUATE RESEARCH U M B C © COPYRIGHT 2014 UNIVERSITY OF MAYLAND, BALTIMORE COUNTY ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. EDITORS: DOMINICK DIMERCURIO II, VANESSA RUEDA, GAGAN SINGH DESIGNER: MORGAN MANTELL DESIGN ASSISTANT: DANIEL GROVE COVER PHOTOGRAPHER: KIT KEARNEY UMBC REVIEW JOURNAL OF UNDERGRADUATE RESEARCH 2014 TABLE OF CONTENTS 11 ROBERT BURTON . ENVIRONMENTAL ENGINEERING TREATMENT OF TETRACYCLINE ANTIBIOTICS IN WATER USING THE UV-H2O 2 PROCESS 31 JANE PAN . MATHEMATICS / COMPUTER SCIENCE LOSS OF METABOLIC OSCILLATIONS IN A MULTICELLULAR COMPUTATIONAL ISLET OF THE PANCREAS 55 JUSTIN CHANG & ANDREW COATES . BIOLOGICAL SCIENCES / MATHEMATICS MODELING THE EFFECTS OF CANONICAL AND ALTERNATIVE PATHWAYS ON INTRACELLULAR CALCIUM LEVELS IN MOUSE OLFACTORY SENSORY NEURONS 83 ISLEEN WRIDE . BIOLOGICAL SCIENCES THE COSTLY TRADE-OFF BETWEEN IMMUNE RESPONSE AND ENHANCED LIFESPAN IN DROSOPHILA MELANOGASTER 99 LAUREN BUCCA . ENGLISH ST. CUTHBERT AND PILGRIMAGE 664-2012AD: THE HERITAGE OF THE PATRON SAINT OF NORTHUMBRIA 123 GRACE CALVIN . PSYCHOLOGY ACCULTURATION, PSYCHOLOGICAL WELL-BEING, AND PARENTING AMONG CHINESE IMMIGRANT FAMILIES 141 ABIGAIL FANARA . MEDIA & COMMUNICATION STUDIES A DIAMOND IS FOREVER: THE CREATION OF A TRADITION 163 LESLIE MCNAMARA . HISTORY “THE LAW WON OVER BIG MONEY”: TOM WATSON AND THE LEO FRANK CASE 181 KEVIN TRIPLETT . GENDER & WOMEN’S STUDIES OVERCOMING REPRODUCTIVE BARRIERS: MEMOIRS OF GAY FATHERHOOD 209 COMFORT UDAH . ENGLISH INSCRIBING THE POSTCOLONIAL SUBJECT: A STUDY ON NIGERIAN WOMEN EDITORS’ INTRODUCTION You have in your hands the fifteenth edition of The UMBC Review: Journal of Undergraduate Research. For a decade and a half, this journal has highlighted the creativity, dedication, and talent UMBC undergraduates possess across disciplines. The university has a commitment to its highly renown undergradu- ate research, and to that end the UMBC Review serves to pres- ent student papers in an academic and prestigious manner. -

Download List of Digitised Manuscripts Hyperlinks, July 2016

ms_shelfmark ms_title ms_dm_link Add Ch 54148 Bull of Pope Alexander III relating to Kilham, http://www.bl.uk/manuscripts/FullDisplay.aspx?ref=Add_Ch_54148&index=0 Yorkshire Add Ch 76659 Confirmations by the Patriarch of http://www.bl.uk/manuscripts/FullDisplay.aspx?index=0&ref=Add_Ch_76659 Constantinople of the stavropegiacal rights of the Monastery of Theotokos Chrysopodariotissa near Kalanos, in the province of Patras in the Peloponnese Add Ch 76660 Confirmations by the Patriarch of http://www.bl.uk/manuscripts/FullDisplay.aspx?index=0&ref=Add_Ch_76660 Constantinople of the stavropegiacal rights of the Monastery of Theotokos Chrysopodariotissa near Kalanos, in the province of Patras in the Peloponnese Add MS 10014 Works of Macarius Alexandrinus, John http://www.bl.uk/manuscripts/FullDisplay.aspx?ref=Add_MS_10014 Chrysostom and others Add MS 10016 Pseudo-Nonnus; Maximus the Peloponnesian; http://www.bl.uk/manuscripts/FullDisplay.aspx?ref=Add_MS_10016 Hilarion Kigalas Add MS 10017 History of Roman Jurisprudence during the http://www.bl.uk/manuscripts/FullDisplay.aspx?ref=Add_MS_10017 Middle Ages, translated into Modern Greek Add MS 10022 Procopius of Gaza, Commentary on Genesis http://www.bl.uk/manuscripts/FullDisplay.aspx?ref=Add_MS_10022 Add MS 10023 Procopius of Gaza, Commentary on the http://www.bl.uk/manuscripts/FullDisplay.aspx?ref=Add_MS_10023 Octateuch Add MS 10024 Vikentios Damodos, On Metaphysics http://www.bl.uk/manuscripts/FullDisplay.aspx?ref=Add_MS_10024 Add MS 10040 Aristotle, Categoriae and other works with http://www.bl.uk/manuscripts/FullDisplay.aspx?ref=Add_MS_10040 -

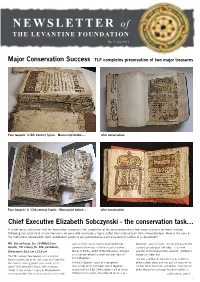

NEWSLETTER of the LEVANTINE FOUNDATION No

NEWSLETTER of THE LEVANTINE FOUNDATION No. 4 July, 2011 Major Conservation Success TLF completes preservation of two major treasures Four Gospels’ in 5th Century Syriac. Manuscript before..... after conservation Four Gospels’ in 13th century Coptic. Manuscript before.... after conservation Chief Executive Elizabeth Sobczynski - the conservation task… It is with great satisfaction that the Foundation announces the completion of the preservation these two major treasures for world heritage. Following two substantial private donations we were able to employ a highly skilled international team from all over Europe. Here is the story of the meticulous conservation work undertaken: patience and perseverance are the essential qualities of a conservator! MS. Deir al-Surian, Syr. 10 [MK6]; Four century when Syrian monks established their 5th or 6th century hand. It is on fine parchment Gospels, 5th century, fls. 104, parchment, community there or in the tenth century when support consisting of 104 folios. Just three Dimensions: 28,2 cm x 23,5 cm Moses of Nisbis, Abbot of the Monastery, brought quarters of the original book survived. Matthew’s an accession of two hundred volumes from his Gospel has been lost. The 5th century Four Gospels is the earliest trip to Baghdad. bound manuscript in the collection and “possibly The text is written in two columns in a mixture the earliest existing gospel manuscript in the The Four Gospels is part of a composite of the carbon black and iron gall ink favoured by world” ((Dr Sebastian Brock, Deir al-Surian, manuscript which had been bound together scribes for its blackness and lustre. One column 2005). -

Nonhuman Voices in Anglo-Saxon Literature and Material Culture

139 4 Assembling and reshaping Christianity in the Lives of St Cuthbert and Lindisfarne Gospels In the previous chapter on the Franks Casket, I started to think about the way in which a thing might act as an assembly, gather- ing diverse elements into a distinct whole, and argued that organic whalebone plays an ongoing role, across time, in this assemblage. This chapter begins by moving the focus from an animal body (the whale) to a human (saintly) body. While saints, in early medieval Christian thought, might be understood as special and powerful kinds of human being – closer to God and his angels in the heavenly hierarchy and capable of interceding between the divine kingdom and the fallen world of mankind – they were certainly not abstract otherworldly spirits. Saints were embodied beings, both in life and after death, when they remained physically present and accessible through their relics, whether a bone, a lock of hair, a fingernail, textiles, a preaching cross, a comb, a shoe. As such, their miracu- lous healing powers could be received by ordinary men, women and children by sight, sound, touch, even smell or taste. Given that they did not simply exist ‘up there’ in heaven but maintained an embodied presence on earth, early medieval saints came to be asso- ciated with very particular places, peoples and landscapes, with built and natural environments, with certain body parts, materi- als, artefacts, sometimes animals. Of the earliest English saints, St Cuthbert is probably one of, if not the, best known and even today remains inextricably linked to the north-east of the country, especially the Holy Island of Lindisfarne and its flora and fauna. -

PARTNERSHIP NEWSLETTER Issue Number 12 Date: February 2020

Website: www.heavenfieldpartnership.org.uk Partnership Dean: Fr. Christopher Warren Telephone: 01434 603119 Partnership Chair: Mr. Joe Ronan Email: [email protected] PARTNERSHIP NEWSLETTER Issue Number 12 Date: February 2020 CONTACT DETAILS: ST. ELIZABETH’S, MINSTERACRES Fr. Jeroen Hoogland (Rector) Rev. David Collins Telephone: 01434 673248 email: [email protected] Website: www.minsteracres.org/st-elizabeth ST. MARY’S, HEXHAM Fr. Christopher Warren Rev. Martin Bell Parish Secretary: Mrs. Judith Chaffey Telephone: 01434 603119 email: [email protected] Website: www.stmaryshexham.org.uk ST. JOHN OF BEVERLEY, HAYDON BRIDGE & ST. WILFRID’S, HALTWHISTLE Telephone: 01434 603119 email: [email protected] Websites: www.stjohnshaydonbridge.com www.rcchurchhaltwhistle.co.uk ST. OSWALD’S, BELLINGHAM Telephone: 01434 603119 email: [email protected] Website: www.stoswaldsbellingham.org.uk The Heavenfield Partnership is a united group of the Roman Catholic parishioners in Bellingham, Haltwhistle, Haydon Bridge, Hexham, Minsteracres, Otterburn and Swinburne, supporting each other in the creation of a vibrant and evangelising community. The God Who Speaks: The Year of The Word NEWS FROM THE PARTNERSHIP “We declare to you what was from the beginning, what we have DEVELOPMENT GROUP heard, what we have seen with our eyes, what we have looked at (Meeting held on 15th January 2020. A set of the minutes of and touched with our hands, concerning the word of life." 1 John this meeting is available from Saint Mary’s Parish Office. A 1:1 summary of each forthcoming meeting will be provided in the In 2018 the Catholic Bishops’ Conference of England and Partnership Bulletin issued after each individual meeting.) Wales called for a Year of the Word under the title, ‘The God Who Speaks’. -

The Codex Amiatinus Maiestas Domini and the Gospel Prefaces of Jerome

The Codex Amiatinus Maiestas Domini and the Gospel Prefaces of Jerome By Peter Darby The manuscript art of the early medieval West was intimately connected to the textual cultures associated with Christian monasticism. The act of pairing illumi- nations and written content opens up myriad possibilities for meaningful corre- spondences to be made between image and text. Such opportunities were regularly exploited in the illuminated manuscripts produced in Britain and Ireland between the sixth and ninth centuries.1 The illuminators of such manuscripts, who were often well acquainted with the Christian Latin culture of late antiquity, produced art that was typically allusive, multivalent, and deliberately complex.2 The simul- taneous presentation of text and image in a manuscript allows the visual material and written words to join together to create something dynamic that is more than the sum of its parts. In such cases even familiar texts and established iconographies can take on new meanings through simple yet meaningful juxtapositions. The process of producing a manuscript involved making a series of conscious choices regarding content, layout, and design. Making a Bible or part-Bible brought the additional considerations of which books to include and omit and which version (or in some cases versions) of the scriptures to follow. Once such choices had been made, the textual content presented within an early medieval Bible was heavily influenced by the exemplars at the copyists’ disposal. The surviving body of evidence suggests that the practice of adorning manuscripts of the Holy Scrip- tures with images emerged as a major intellectual concern from the fifth century onwards.3 This development introduced an expressive element into the process of bookmaking, which counterbalanced the more routine, if no less important, This essay is dedicated to the memory of Jennifer O’Reilly, who generously took the time to discuss the Codex Amiatinus with me on several occasions; our conversations helped to improve this article beyond measure. -

Nonhuman Voices in Anglo-Saxon Literature and Material Culture

i NONHUMAN VOICES IN ANGLO- SAXON LITERATURE AND MATERIAL CULTURE ii Series editors: Anke Bernau and David Matthews Series founded by: J. J. Anderson and Gail Ashton Advisory board: Ruth Evans, Nicola McDonald, Andrew James Johnston, Sarah Salih, Larry Scanlon and Stephanie Trigg The Manchester Medieval Literature and Culture series publishes new research, informed by current critical methodologies, on the literary cultures of medieval Britain (including Anglo- Norman, Anglo- Latin and Celtic writings), including post- medieval engagements with and representations of the Middle Ages (medievalism). ‘Literature’ is viewed in a broad and inclusive sense, embracing imaginative, historical, political, scientific, dramatic and religious writings. The series offers monographs and essay collections, as well as editions and translations of texts. Titles Available in the Series The Parlement of Foulys (by Geoffrey Chaucer) D. S. Brewer (ed.) Language and imagination in the Gawain- poems J. J. Anderson Water and fire:The myth of the Flood in Anglo- Saxon England Daniel Anlezark Greenery: Ecocritical readings of late medieval English literature Gillian Rudd Sanctity and pornography in medieval culture:On the verge Bill Burgwinkle and Cary Howie In strange countries: Middle English literature and its afterlife: Essays in Memory of J. J. Anderson David Matthews (ed.) A knight’s legacy: Mandeville and Mandevillian lore in early modern England Ladan Niayesh (ed.) Rethinking the South English legendaries Heather Blurton and Jocelyn Wogan- Browne (eds) -

The Wonders of Early Medieval Christian

applyparastyle “fig//caption/p[1]” parastyle “FigCapt” Mediaevistik 32 . 2019 55 2020 Albrecht Classen The University of Arizona 00 The Book of Kells - The Wonders of Early Medieval 00 Christian Manuscript Illuminations Within a Pagan 45 World 70 For a long time now, we have been misled by the general notion that the fall of the 2020 Roman Empire at the end of the fifth century brought about a devastating decline of culture and civilization. The Germanic peoples were allegedly barbaric, and what they created upon the ruins of their predecessors could have been nothing but primitive and little sophisticated. Research has, of course, confirmed already in a variety of approa- ches and many specialized studies that the situation on the ground was very different,1 but it seems rather difficult to deconstruct this mythical notion even today, as much as it needs to be corrected and extensively qualified. Recently, Deborah Deliyannis, Hendrik Dey, and Paolo Squatriti have published a volume treating an intriguing se- lection of fifty objects that could represent the early Middle Ages, each one of them proving by itself that the arts and technology to produce those objects continued to be extraordinarily sophisticated and impressive, and this well beyond the Roman period and well before the rise of the Gothic era.2 Those objects include ceremonial regalia, mosaic pavements, medallions, coins, stirrups, buildings, fibula, tunics, oil lamps, ships, and castles. The quality and aesthetic appeal of all of them is stunning, but they make up, of course, only a selection and do not reveal the more common conditions of the ordinary people. -

Christina Duffy Visualising Our Cultural Heritage: Why Science

LOOKING Grey Institute AT IMAGES vos taedium facit delirus Dr Christina Duffy The British Library Visualising Our Cultural Heritage: Why Science Shouldn’t Get Lost in Digitisation Introduction When preparing a piece of work it is often expected (nay, demanded!) that one should include an image to support the primary content. But what if the image is the primary content? For imaging scientists, this is often the case. Images and data visualisations are becoming increasingly more accepted as scientific objects in their own right, without the need for caption or explanation. As cultural heritage institutions (galleries, libraries, archives, and museums) seek new ways to explore their collections, there is a growing appetite to integrate science and technology into all aspects of mission and vision statements. This year alone has welcomed science at the fore of several major London exhibitions including those at the British Museum (Ancient lives, new discoveries, 22 May – 30 November 2014) and the National Gallery (Making Colour, 18 June – 7 September 2014) where images are used to convey new methods of thinking and to reveal new discoveries. The British Museum claims to use “the latest scientific techniques to shed new light on ancient cultures”, while the National Gallery “invites you on an artistic scientific voyage of discovery.” Positively tantalising! In this piece, scientific imaging techniques adapted to suit cultural heritage needs are described, some examples of imaging science at the British Library are shared, and the consequences of replacing physical book and manuscript consultation with digital examination are considered. The Evolution of Imaging Science Imaging science is an evolving multidisciplinary field encompassing image capture, analysis, processing, and visualisation. -

Anglo Saxon-Monastic Artefact Box: Complete Box

ANGLO SAXON-Monastic ARTEFACT BOX ANGLO SAXON-MONASTIC ARTEFACT BOX: COMPLETE BOX 1 Whetstone on cord 8 Water Bottle & Stopper on Leather Strap 2 Book Stamp 9 Hexham Plaque [Copper mounted on wood] in canvas pouch 3 3 x Candles 10 Example of Illuminated Manuscript 4 Ink Pot and Cap 11 Scribe’s Knife 5 8x Mussel Shells in Canvas Bag 12 Round Knife 6 3x Writing Quills 13 St John’s Gospel & Satchel 7 Flail 14 AS Monastic Loan Box-Risk Assessment 15 Artefact Box Booklet–AS Monastic Acknowledgements The artefacts were made by Emma Berry and Andrew Bates of Phenix Studios Ltd of Hexham, Northumberland. http://www.phenixstudios.com/ ARTEFACT BOX: ANGLO SAXON-MONASTIC Item: 1 Brief Description: Whetstone Further Information: Used to sharpen knives, tools etc. Some whetstones were carved and decorated like this one found at the 7thcentury Sutton Hoo burial : https://www.google.com/culturalinstitute/beta/search?q=sutt on%20hoo%20whetstone The leather strap allows it to be hung around the neck or on a belt ready for use. Explore: What does the fact whetstones were carved and decorated tell us about the importance of a whetstone in Anglo-Saxon life? Why would a whetstone have been such an important item for an Anglo- Saxon? ARTEFACT BOX: ANGLO SAXON-MONASTIC Item: 2 Brief Description: Book Stamp Further Information: The original book stamp was found at Winchester and was made from metal. This copy is made from bone and oak. Many books of this time had leather bindings and covers. For example see Item 13 in this Box. -

Navigation, Search a Carpet Page from the Lindisfarne Gospels Carpet

Carpet page From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Jump to: navigation, search A carpet page from the Lindisfarne Gospels Carpet pages are a characteristic feature of Insular illuminated manuscripts. They are pages of mainly geometrical ornamentation, which may include repeated animal forms, typically placed at the beginning of each of the four Gospels in Gospel Books. The designation "carpet page" is used to describe those pages in Christian, Islamic, or Jewish illuminated manuscripts that contain little or no text and which are filled entirely with decorative motifs.[1][2][3] They are distinct from pages devoted to highly decorated historiated initials, though the style of decoration may be very similar.[4] Carpet pages are wholly devoted to ornamentation with brilliant colors, active lines, and complex patterns of interlace. They are normally symmetrical, or very nearly so, about both a horizontal and vertical axis, though for example the page at right is only symmetrical about a vertical axis. Some art historians find their origin in similar Coptic decorative book pages,[5] and they also clearly borrow from contemporary metalwork decoration. Oriental carpets, or other textiles, may themselves have been influences. The tooled leather book binding of the St Cuthbert Gospel represents a simple carpet page in another medium,[6] and the few surviving treasure bindings - metalwork book covers or book shrines - from the same period, such as that on the Lindau Gospels, are also close parallels.[7] Roman floor mosaics seen in post-Roman Britain, are also cited as a possible source.[8] The Hebrew Codex Cairensis, from 9th century Galilee, also contains a similar type of page, but stylistically very different.