Origins and Interpretations of Folio 3V in the Book of Durrow

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Discovery of a Watermark on the St Cuthbert Gospel Using Colour Space Analysis

The Discovery of a Watermark on the St Cuthbert Gospel using Colour Space Analysis Christina Duffy 1. Introduction Watermarks since their introduction in the thirteenth century have been used as a method of establishing the provenance and origin of paper, identifying mill trademarks and locations, and determining the sizes and intended functions of papers. Watermarks are designs such as a name, initials, or a decorative motif impressed on paper in a similar way to chain and laid lines.1 A watermark design was incorporated by manipulating wire into a recognizable shape and affixing it to the mould. The thickness of the paper is reduced over regions of wire which results in the familiar appearance of watermarks, chain lines, and laid lines when paper is held up to the light. Chain and laid lines are important even if they obscure the watermark design as their relative positions can aid in determining the orientation of the paper when the pages were laid out for printing. Imaging of watermarks has been problematic for curators and scholars with partial marks often found in non-adjacent gutters owing to the ordering and cutting of the folios. Techniques such as tracing, transmitted light and the Dylux method2 have been used in the past. More sophisticated methods such as beta radiation, IR imaging and thermography have improved results, but are still highly dependent on the material and only successful in certain cases. Best results are usually found when the watermarked folio can be accessed from both sides to allow light to pass through from the back, and the image to be photographically captured from the front. -

Early Medieval Europe

Early Medieval Europe 1 Early Medieval Sites in Europe 2 Figure 16-2 Pair of Merovingian looped fibulae, from Jouy-le-Comte, France, mid-sixth century. Silver gilt worked in filigree, with inlays of garnets and other stones, 4” high. Musée d’Archéologie nationale, Saint-Germain-en-Laye. 3 Heraldic Motifs Figure 16-3 Purse cover, from the Sutton Hoo ship burial in Suffolk, England, ca. 625. Gold, glass, and cloisonné garnets, 7 1/2” long. British Museum, London. 4 5 Figure 16-4 Animal-head post, from the Viking ship burial, Oseberg, Norway, ca. 825. Wood, head 5” high. University Museum of National Antiquities, Oslo. 6 Figure 16-5 Wooden portal of the stave church at Urnes, Norway, ca. 1050–1070. 7 Figure 16-6 Man (symbol of Saint Matthew), folio 21 verso of the Book of Durrow, possibly from Iona, Scotland, ca. 660–680. Ink and tempera on parchment, 9 5/8” X 6 1/8”. Trinity College Library, Dublin. 8 Figure 16-1 Cross-inscribed carpet page, folio 26 verso of the Lindisfarne Gospels, from Northumbria, England, ca. 698–721. Tempera on vellum, 1’ 1 1/2” X 9 1/4”. British Library, London. 9 Figure 16-7 Saint Matthew, folio 25 verso of the Lindisfarne Gospels, from Northumbria, England, ca. 698–721. Tempera on vellum, 1’ 1 1/2” X 9 1/4”. British Library, London. 10 Figure 16-8 Chi-rho-iota (XPI) page, folio 34 recto of the Book of Kells, probably from Iona, Scotland, late eighth or early ninth century. Tempera on vellum, 1’ 1” X 9 1/2”. -

Thomas Newbolt: Drama Painting – a Modern Baroque

NAE MAGAZINE i NAE MAGAZINE ii CONTENTS CONTENTS 3 EDITORIAL Off Grid - Daniel Nanavati talks about artists who are working outside the established art market and doing well. 6 DEREK GUTHRIE'S FACEBOOK DISCUSSIONS A selection of the challenging discussions on www.facebook.com/derekguthrie 7 THE WIDENING CHASM BETWEEN ARTISTS AND CONTEMPORARY ART David Houston, curator and academic, looks at why so may contemporary artists dislike contemporary art. 9 THE OSCARS MFA John Steppling, who wrote the script for 52nd Highway and worked in Hollywood for eight years, takes a look at the manipulation of the moving image makers. 16 PARTNERSHIP AGREEMENT WITH PLYMOUTH COLLEGE OF ART Our special announcement this month is a partnering agreement between the NAE and Plymouth College of Art 18 SPEAKEASY Tricia Van Eck tells us that artists participating with audiences is what makes her gallery in Chicago important. 19 INTERNET CAFÉ Tom Nakashima, artist and writer, talks about how unlike café society, Internet cafés have become. Quote: Jane Addams Allen writing on the show: British Treasures, From the Manors Born 1984 One might almost say that this show is the apotheosis of the British country house " filtered through a prism of French rationality." 1 CONTENTS CONTENTS 21 MONSTER ROSTER INTERVIEW Tom Mullaney talks to Jessica Moss and John Corbett about the Monster Roster. 25 THOUGHTS ON 'CAST' GRANT OF £500,000 Two Associates talk about one of the largest grants given to a Cornwall based arts charity. 26 MILWAUKEE MUSEUM'S NEW DESIGN With the new refurbishment completed Tom Mullaney, the US Editor, wanders around the inaugural exhibition. -

Umbc Review Journal of Undergraduate Research U M B C

UMBC2014 UMBC REVIEW JOURNAL OF UNDERGRADUATE RESEARCH U M B C © COPYRIGHT 2014 UNIVERSITY OF MAYLAND, BALTIMORE COUNTY ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. EDITORS: DOMINICK DIMERCURIO II, VANESSA RUEDA, GAGAN SINGH DESIGNER: MORGAN MANTELL DESIGN ASSISTANT: DANIEL GROVE COVER PHOTOGRAPHER: KIT KEARNEY UMBC REVIEW JOURNAL OF UNDERGRADUATE RESEARCH 2014 TABLE OF CONTENTS 11 ROBERT BURTON . ENVIRONMENTAL ENGINEERING TREATMENT OF TETRACYCLINE ANTIBIOTICS IN WATER USING THE UV-H2O 2 PROCESS 31 JANE PAN . MATHEMATICS / COMPUTER SCIENCE LOSS OF METABOLIC OSCILLATIONS IN A MULTICELLULAR COMPUTATIONAL ISLET OF THE PANCREAS 55 JUSTIN CHANG & ANDREW COATES . BIOLOGICAL SCIENCES / MATHEMATICS MODELING THE EFFECTS OF CANONICAL AND ALTERNATIVE PATHWAYS ON INTRACELLULAR CALCIUM LEVELS IN MOUSE OLFACTORY SENSORY NEURONS 83 ISLEEN WRIDE . BIOLOGICAL SCIENCES THE COSTLY TRADE-OFF BETWEEN IMMUNE RESPONSE AND ENHANCED LIFESPAN IN DROSOPHILA MELANOGASTER 99 LAUREN BUCCA . ENGLISH ST. CUTHBERT AND PILGRIMAGE 664-2012AD: THE HERITAGE OF THE PATRON SAINT OF NORTHUMBRIA 123 GRACE CALVIN . PSYCHOLOGY ACCULTURATION, PSYCHOLOGICAL WELL-BEING, AND PARENTING AMONG CHINESE IMMIGRANT FAMILIES 141 ABIGAIL FANARA . MEDIA & COMMUNICATION STUDIES A DIAMOND IS FOREVER: THE CREATION OF A TRADITION 163 LESLIE MCNAMARA . HISTORY “THE LAW WON OVER BIG MONEY”: TOM WATSON AND THE LEO FRANK CASE 181 KEVIN TRIPLETT . GENDER & WOMEN’S STUDIES OVERCOMING REPRODUCTIVE BARRIERS: MEMOIRS OF GAY FATHERHOOD 209 COMFORT UDAH . ENGLISH INSCRIBING THE POSTCOLONIAL SUBJECT: A STUDY ON NIGERIAN WOMEN EDITORS’ INTRODUCTION You have in your hands the fifteenth edition of The UMBC Review: Journal of Undergraduate Research. For a decade and a half, this journal has highlighted the creativity, dedication, and talent UMBC undergraduates possess across disciplines. The university has a commitment to its highly renown undergradu- ate research, and to that end the UMBC Review serves to pres- ent student papers in an academic and prestigious manner. -

K 03-UP-004 Insular Io02(A)

By Bernard Wailes TOP: Seventh century A.D., peoples of Ireland and Britain, with places and areas that are mentioned in the text. BOTTOM: The Ogham stone now in St. Declan’s Cathedral at Ardmore, County Waterford, Ireland. Ogham, or Ogam, was a form of cipher writing based on the Latin alphabet and preserving the earliest-known form of the Irish language. Most Ogham inscriptions are commemorative (e.g., de•fin•ing X son of Y) and occur on stone pillars (as here) or on boulders. They date probably from the fourth to seventh centuries A.D. who arrived in the fifth century, occupied the southeast. The British (p-Celtic speakers; see “Celtic Languages”) formed a (kel´tik) series of kingdoms down the western side of Britain and over- seas in Brittany. The q-Celtic speaking Irish were established not only in Ireland but also in northwest Britain, a fifth- THE CASE OF THE INSULAR CELTS century settlement that eventually expanded to become the kingdom of Scotland. (The term Scot was used interchange- ably with Irish for centuries, but was eventually used to describe only the Irish in northern Britain.) North and east of the Scots, the Picts occupied the rest of northern Britain. We know from written evidence that the Picts interacted extensively with their neighbors, but we know little of their n decades past, archaeologists several are spoken to this day. language, for they left no texts. After their incorporation into in search of clues to the ori- Moreover, since the seventh cen- the kingdom of Scotland in the ninth century, they appear to i gin of ethnic groups like the tury A.D. -

Download List of Digitised Manuscripts Hyperlinks, July 2016

ms_shelfmark ms_title ms_dm_link Add Ch 54148 Bull of Pope Alexander III relating to Kilham, http://www.bl.uk/manuscripts/FullDisplay.aspx?ref=Add_Ch_54148&index=0 Yorkshire Add Ch 76659 Confirmations by the Patriarch of http://www.bl.uk/manuscripts/FullDisplay.aspx?index=0&ref=Add_Ch_76659 Constantinople of the stavropegiacal rights of the Monastery of Theotokos Chrysopodariotissa near Kalanos, in the province of Patras in the Peloponnese Add Ch 76660 Confirmations by the Patriarch of http://www.bl.uk/manuscripts/FullDisplay.aspx?index=0&ref=Add_Ch_76660 Constantinople of the stavropegiacal rights of the Monastery of Theotokos Chrysopodariotissa near Kalanos, in the province of Patras in the Peloponnese Add MS 10014 Works of Macarius Alexandrinus, John http://www.bl.uk/manuscripts/FullDisplay.aspx?ref=Add_MS_10014 Chrysostom and others Add MS 10016 Pseudo-Nonnus; Maximus the Peloponnesian; http://www.bl.uk/manuscripts/FullDisplay.aspx?ref=Add_MS_10016 Hilarion Kigalas Add MS 10017 History of Roman Jurisprudence during the http://www.bl.uk/manuscripts/FullDisplay.aspx?ref=Add_MS_10017 Middle Ages, translated into Modern Greek Add MS 10022 Procopius of Gaza, Commentary on Genesis http://www.bl.uk/manuscripts/FullDisplay.aspx?ref=Add_MS_10022 Add MS 10023 Procopius of Gaza, Commentary on the http://www.bl.uk/manuscripts/FullDisplay.aspx?ref=Add_MS_10023 Octateuch Add MS 10024 Vikentios Damodos, On Metaphysics http://www.bl.uk/manuscripts/FullDisplay.aspx?ref=Add_MS_10024 Add MS 10040 Aristotle, Categoriae and other works with http://www.bl.uk/manuscripts/FullDisplay.aspx?ref=Add_MS_10040 -

The Date and Context of the Glamis, Angus, Carved Pictish Stones Lloyd Laing*

Proc Soc Antiq Scot, 131 (2001), 223–239 The date and context of the Glamis, Angus, carved Pictish stones Lloyd Laing* ABSTRACT The widely accepted eighth-century dating for the Pictish relief-decorated cross-slabs known as Glamis 2 and Glamis 1 is reviewed, and an alternative ninth-century date advanced for both monuments. It is suggested that the carving on front and back of Glamis 2 was contemporaneous, and that both monuments belong to the Aberlemno School. GLAMIS 2 DESCRIPTION The Glamis 2 stone (Allen & Anderson’s scheme, 1903, pt III, 3–4) stands in front of the manse at Glamis, Angus, and its measurements — 2.76 m by 1.5 m by 0.24 m — make it one of the larger Class II slabs. It is probably a re-used Bronze Age standing stone as there appear to be some cup- marks incised on the base of the cross face. Holes have been drilled in the relatively recent past at the base of the sides, presumably for support struts. Viewed from the front (cross) face the slab is pedimented, the ornament being partly incised, partly in relief (illus 1). The cross is in shallow relief, has double hollow armpits and a ring delimited by incised double lines except in the bottom right hand corner, where the ring is absent. It is decorated with interlace, with a central interlaced roundel on the crossing. The interlace on the cross-arms and immediately above the roundel is zoomorphic. At the top of the pediment is a pair of beast heads, now very weathered, with what may be a human head between them, in low relief. -

Ancient Foundations Marshall High School Unit Five AD * How the Irish Saved Civilization

The Dark Ages Marshall High School Mr. Cline Western Civilization I: Ancient Foundations Marshall High School Unit Five AD * How the Irish Saved Civilization • Christianity's Impact on Insular Art • Ireland's Golden Age is closely tied with the spread of Christianity. • As Angles and Saxons began colonizing the old Roman province of Brittania, Christians living in Britain fled to the relative safety of Ireland. • These Christians found themselves isolated from their neighbors on the mainland and essentially cut off from the influence of the Roman Catholic Church. • This isolation, combined with the mostly agrarian society of Ireland, resulted in a very different form of Christianity. • Instead of establishing a centralized hierarchy, like the Roman Catholic Church, Irish Christians established monasteries. • Monasticism got an early start in Ireland, and monasteries began springing up across the countryside. • The Irish did not just build monasteries in Ireland. * How the Irish Saved Civilization • Christianity's Impact on Insular Art • They sent missionaries to England to begin reconverting their heathen neighbors. • From there they crossed the channels, accelerating the conversion of France, Germany and the Netherlands and establishing monasteries from Poitiers to Vienna. • These monasteries became centers of art and learning, producing art of unprecedented complexity, like the Book of Kells, and great scholars, like the Venerable Bede (Yes, the guy who wrote the Anglo Saxon History of Britain was indeed Irish!) * How the Irish Saved Civilization • Christianity's Impact on Insular Art * How the Irish Saved Civilization • Christianity's Impact on Insular Art • Over time, Ireland became the cultural and religious leader of Northwestern Europe. -

July 1984 Number 19 Editor

July 1984 Number 19 Editor: Flavia Swann Editorial Office: The Editor has been asked to compile an updated applied this argument to such subjects as the scale of Department of version of the Register of post-graduate taught Anglo-Norman buildings, the Lombard sculpture on History of Art & Design courses in History of Art and Design in British the cathedrals of Speyer and Mainz, the pointed arch North Staffordshire Universities and Polytechnics, which was first at Cluny Abbey, and finally to Suger's early Gothic Polytechnic published in Bulletin No 8 in February 1979. This church of St Denis. College Road will clearly take some time as much has changed since Stoke-on-Trent ST4 2DE iii. Architectural history in the service of the Telephone: 1979 including the initiation of new courses. It would (0782)45531 be much appreciated if members involved in such Renaissance church courses could send to the Editor revised and new John Onians copy on postgraduate taught courses. All buildings in a sense assert their position in the history of architecture. This was especially true in the The timetable for forthcoming Bulletins is as follows: Renaissance period when builders could choose from Bulletin 20 Publication mid November a range of styles. Gothic or Classical, primitive Deadline for copy 1 October 1984 Classical or developed Classical and even Greek or Bulletin 21 Publication mid February Israelite. The popes as leaders of the Catholic Church Deadline for copy 31 December 1984 had also to choose ways of building which expressed Bulletin 22 Publication mid July their different views of their position in the history of Deadline for copy 24 May 1985 religion. -

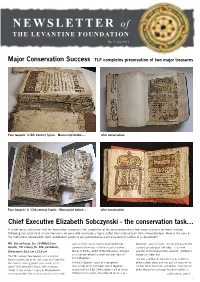

NEWSLETTER of the LEVANTINE FOUNDATION No

NEWSLETTER of THE LEVANTINE FOUNDATION No. 4 July, 2011 Major Conservation Success TLF completes preservation of two major treasures Four Gospels’ in 5th Century Syriac. Manuscript before..... after conservation Four Gospels’ in 13th century Coptic. Manuscript before.... after conservation Chief Executive Elizabeth Sobczynski - the conservation task… It is with great satisfaction that the Foundation announces the completion of the preservation these two major treasures for world heritage. Following two substantial private donations we were able to employ a highly skilled international team from all over Europe. Here is the story of the meticulous conservation work undertaken: patience and perseverance are the essential qualities of a conservator! MS. Deir al-Surian, Syr. 10 [MK6]; Four century when Syrian monks established their 5th or 6th century hand. It is on fine parchment Gospels, 5th century, fls. 104, parchment, community there or in the tenth century when support consisting of 104 folios. Just three Dimensions: 28,2 cm x 23,5 cm Moses of Nisbis, Abbot of the Monastery, brought quarters of the original book survived. Matthew’s an accession of two hundred volumes from his Gospel has been lost. The 5th century Four Gospels is the earliest trip to Baghdad. bound manuscript in the collection and “possibly The text is written in two columns in a mixture the earliest existing gospel manuscript in the The Four Gospels is part of a composite of the carbon black and iron gall ink favoured by world” ((Dr Sebastian Brock, Deir al-Surian, manuscript which had been bound together scribes for its blackness and lustre. One column 2005). -

Gothic Architecture the Gothic Period Began with the Construction of the Choir at St

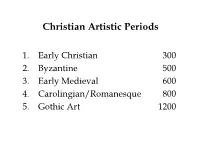

Christian Artistic Periods 1. Early Christian 300 2. Byzantine 500 3. Early Medieval 600 4. Carolingian/Romanesque 800 5. Gothic Art 1200 The Good Shepherd in the Catacomb of Saints Pietro and Marcellino, Rome (E. Christian, early 4th century CE). Edicule, Church of the Holy Sepulchre, Jerusalem Saint Apollinaire as the Good Shepherd, Early Christian, mosaic, St. Apollinaire in Classe, Ravenna, Italy. Christ the Good Shepherd, mosaic, Mausoleum of Galla Placidia, Ravenna Terminology • Catacomb • Fresco • Basilica • Longitudinal plan • Facade • Central plan • Atrium • Latin Cross Plan • Narthex • Mosiacs • Nave • Altar • Apse • Transept Justinian and Attendants (Byzantine, c. 547 CE). Mosaic. San Vitale, Ravenna, Italy Anthemius and Isidorus. Hagia Sophia, (Byzantine, 532-537 CE) Istanbul, Turkey. Pantocrator, Byzantine, mosaic, Hagia Sophia Madonna Enthroned tempera and gold leaf on panel, Byzantine, 1300 ce Early Christian and Byzantine Themes and Concepts: • basilica versus central plan • West versus East • church and state • Mosaics, tempera, and gold-leaf • icon, iconography Purse Cover from Sutton Hoo Ship Burial, Suffolk, England, before 655, gold and enamel, 7.5 ‘ long Animal-Head Post from Oseberg Ship Burial, Maritime Museum in Stockholm, Sweden, c. 825, wood The High Cross of Muiredach, west face, gets its name from an inscription at the base of the west face, saying it was erected by Muiredach. 10th or possibly 9th century, located at the ruined monastic site of Monasterboice, in County Louth, Ireland. Irish high crosses are internationally recognized icons of early medieval Ireland. c. 850, sandstone, 19’ The Lindisfarne Gospels is a manuscript that contains the Gospels of the four Evangelists Mark, John, Luke, and Matthew. -

Nonhuman Voices in Anglo-Saxon Literature and Material Culture

139 4 Assembling and reshaping Christianity in the Lives of St Cuthbert and Lindisfarne Gospels In the previous chapter on the Franks Casket, I started to think about the way in which a thing might act as an assembly, gather- ing diverse elements into a distinct whole, and argued that organic whalebone plays an ongoing role, across time, in this assemblage. This chapter begins by moving the focus from an animal body (the whale) to a human (saintly) body. While saints, in early medieval Christian thought, might be understood as special and powerful kinds of human being – closer to God and his angels in the heavenly hierarchy and capable of interceding between the divine kingdom and the fallen world of mankind – they were certainly not abstract otherworldly spirits. Saints were embodied beings, both in life and after death, when they remained physically present and accessible through their relics, whether a bone, a lock of hair, a fingernail, textiles, a preaching cross, a comb, a shoe. As such, their miracu- lous healing powers could be received by ordinary men, women and children by sight, sound, touch, even smell or taste. Given that they did not simply exist ‘up there’ in heaven but maintained an embodied presence on earth, early medieval saints came to be asso- ciated with very particular places, peoples and landscapes, with built and natural environments, with certain body parts, materi- als, artefacts, sometimes animals. Of the earliest English saints, St Cuthbert is probably one of, if not the, best known and even today remains inextricably linked to the north-east of the country, especially the Holy Island of Lindisfarne and its flora and fauna.