July 1984 Number 19 Editor

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

North Vorthumberland

Midlothian Vice-county 83 Scarce, Rare & Extinct Vascular Plant Register Silene viscaria Vicia orobus (© Historic Scotland Ranger Service) (© B.E.H. Sumner) Barbara E.H. Sumner 2014 Rare Plant Register Midlothian Asplenium ceterach (© B.E.H. Sumner) The records for this Register have been selected from the databases held by the Botanical Society of Britain and Ireland. These records were made by botanists, most of whom were amateur and some of whom were professional, employed by government departments or undertaking environmental impact assessments. This publication is intended to be of assistance to conservation and planning organisations and authorities, district and local councils and interested members of the public. Acknowledgements My thanks go to all those who have contributed records over the years, and especially to Douglas R. McKean and the late Elizabeth P. Beattie, my predecessors as BSBI Recorders for Midlothian. Their contributions have been enormous, and Douglas continues to contribute enthusiastically as Recorder Emeritus. Thanks also to the determiners, especially those who specialise in difficult plant groups. I am indebted to David McCosh and George Ballantyne for advice and updates on Hieracium and Rubus fruticosus microspecies, respectively, and to Chris Metherell for determinations of Euphrasia species. Chris also gave guidelines and an initial template for the Register, which I have customised for Midlothian. Heather McHaffie, Phil Lusby, Malcolm Fraser, Caroline Peacock, Justin Maxwell and Max Coleman have given useful information on species recovery programmes. Claudia Ferguson-Smyth, Nick Stewart and Michael Wilcox have provided other information, much appreciated. Staff of the Library and Herbarium at the Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh have been most helpful, especially Graham Hardy, Leonie Paterson, Sally Rae and Adele Smith. -

Scotland and the North

Edinburgh Research Explorer Scotland and the North Citation for published version: Fielding, P 2018, Scotland and the North. in D Duff (ed.), Oxford Handbook of British Romanticism. Oxford Handbooks, Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp. 106-120. Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Document Version: Peer reviewed version Published In: Oxford Handbook of British Romanticism Publisher Rights Statement: This is the accepted version of the following chapter: Fielding, P 2018, Scotland and the North. in D Duff (ed.), Oxford Handbook of British Romanticism. Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp. 106-120. Reproduced by permission of Oxford University Press https://global.oup.com/academic/product/the-oxford-handbook-of-british-romanticism- 9780199660896?cc=gb&lang=en&# General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 29. Sep. 2021 1 SCOTLAND AND THE NORTH Penny Fielding To think about Romanticism in national terms -- the possibility that there might be a ‘Scottish Romanticism’ distinct from an English, British, German, European, or any other national form -- asks us first to set down some ideas about space and time upon which such a concept might be predicated. -

Scotland, Social and Domestic. Memorials of Life and Manners in North Britain

SCOTLAND SOCIAL AND DOMESTIC MEMORIALS OF LIFE AND MANNERS IN NORTH BRITAIN ReV. CHARLES ROGERS, LL.D., ES.A. Scot. HISTORIOGRAPHER TO THE HISTORICAL SOCIETY OE GREAT BRITAIN. %,»a# LONDON CHARLES GEIFFIN AND CO. STATIONERS' HALL COURT 1SG9 THE GRAMPIAN CLUB. Office-bearers, 1869. HIS GEACE THE DUKE OF ARGYLE, K.T. THE MOST HON. THE MARQUESS OF BUTE. THE RIGHT HON. THE EARL OF DALHOUSIE, K.T. THE RIGHT HON. THE EARL OF ROSSLYN. SIR RODERICK I. MURCHISON, Bart., K.C.B., F.R.S., D.C.L., LL.D., Hon. Member of the Royal Society of Edinburgh, and Member of the Institute of France. SIR JAMES Y. SIMPSON, Bart., M.D., F.R.S.E., F.S.A. Scot. GEORGE VERE IRVING, Esq., of Newton. ROBERT CRAWFORD, Esq., of Westbrook, F.A.S.L., London. Council. THE RIGHT HON. THE EARL OF MAR. COLONEL SYKES, M.P. SIR PATRICK M. COLQUHOUN, Q.C., LL.D., F.R.S.L. GEORGE STIRLING HOME DRUMMOND, Esq., of Blair Drum- mond. T. L. KINGTON OLIPHANT, Esq., of Gask. J. ROSS COULTHART, Esq., F.S.A. Scot., F.R.S. Lit. CHARLES MACKAY, Esq., LL.D. REV. CHARLES ROGERS, LL.D., F.S.A. Scot. REV. JOHN GRANT WRIGHT, LL.D. WILLIAM EUING, Esq., F.R.S E., F.S.A. Scot. F. W. RAMSAY, Esq., M.D., of Inveresk. GEORGE EDWIN SWITHINBANK, Esq., LL.D., F.S.A. Scot. RICHARD BENNETT, Esq. GEORGE W. GIBSON, Esq. Secretarrj. LOUIS CHARLES ALEXANDER, Esq. A. GLIDDON, Esq., The City Bank, Tottenham Court Road, W. -

Thomas Newbolt: Drama Painting – a Modern Baroque

NAE MAGAZINE i NAE MAGAZINE ii CONTENTS CONTENTS 3 EDITORIAL Off Grid - Daniel Nanavati talks about artists who are working outside the established art market and doing well. 6 DEREK GUTHRIE'S FACEBOOK DISCUSSIONS A selection of the challenging discussions on www.facebook.com/derekguthrie 7 THE WIDENING CHASM BETWEEN ARTISTS AND CONTEMPORARY ART David Houston, curator and academic, looks at why so may contemporary artists dislike contemporary art. 9 THE OSCARS MFA John Steppling, who wrote the script for 52nd Highway and worked in Hollywood for eight years, takes a look at the manipulation of the moving image makers. 16 PARTNERSHIP AGREEMENT WITH PLYMOUTH COLLEGE OF ART Our special announcement this month is a partnering agreement between the NAE and Plymouth College of Art 18 SPEAKEASY Tricia Van Eck tells us that artists participating with audiences is what makes her gallery in Chicago important. 19 INTERNET CAFÉ Tom Nakashima, artist and writer, talks about how unlike café society, Internet cafés have become. Quote: Jane Addams Allen writing on the show: British Treasures, From the Manors Born 1984 One might almost say that this show is the apotheosis of the British country house " filtered through a prism of French rationality." 1 CONTENTS CONTENTS 21 MONSTER ROSTER INTERVIEW Tom Mullaney talks to Jessica Moss and John Corbett about the Monster Roster. 25 THOUGHTS ON 'CAST' GRANT OF £500,000 Two Associates talk about one of the largest grants given to a Cornwall based arts charity. 26 MILWAUKEE MUSEUM'S NEW DESIGN With the new refurbishment completed Tom Mullaney, the US Editor, wanders around the inaugural exhibition. -

Journal of Roman Pottery Studies 15 Belongs to the Publishers Oxbow Books and It Is Their Copyright

This pdf of your paper in Journal of Roman Pottery Studies 15 belongs to the publishers Oxbow Books and it is their copyright. As author you are licenced to make up to 50 offprints from it, but beyond that you may not publish it on the World Wide Web until three years from publication (October 2015), unless the site is a limited access intranet (password protected). If you have queries about this please contact the editorial department at Oxbow Books (editorial@ oxbowbooks.com). Journal of Roman Pottery Studies Journal of Roman Pottery Studies Volume 15 edited by Steven Willis ISBN: 978-1-84217-500-2 © Oxbow Books 2012 www.oxbowbooks.com for The Study Group for Roman Pottery Dedication The Study Group Committee dedicate this volume to Ted Connell who has given so much to the Group over many years. Ted joined the Group over 25 years ago; he has served as Group Treasurer (1994–2003) and developed the Group’s Website from 2001. Thank you Ted! Contents Contributors to this Journal ix Editorial x Obituaries Gillian Braithwaite by Richard Reece xi John Dore by David Mattingly xii Vivien Swan by Steven Willis xiv 1 Beyond the confi nes of empire: a reassessment of the Roman coarse wares from Traprain Law 1 Louisa Campbell 2 Romano-British kiln building and fi ring experiments: two recent kilns 26 Beryl Hines 3 New data concerning pottery production in the south-western part of Gallia Belgica, in light of the A29 motorway excavations 39 Cyrille Chaidron 4 A characterisation of coastal pottery in the north of France (Nord/Pas-de-Calais) 61 Raphaël Clotuche and Sonja Willems 5 Raetian mortaria in Britain 76 Katharine F. -

![Scottish Record Society. [Publications]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5606/scottish-record-society-publications-815606.webp)

Scottish Record Society. [Publications]

00 HANDBOUND AT THE L'.VU'ERSITY OF TORONTO PRESS (SCOTTISH RECORD SOCIETY, ^5^ THE Commissariot IRecorb of EMnbutGb. REGISTER OF TESTAMENTS. PART III. VOLUMES 81 TO iji—iyoi-iSoo. EDITED BY FRANCIS J. GRANT, W.S., ROTHESAY HERALD AND LYON CLEKK. EDINBURGH : PRINTED FOR THE SOCIETY BY JAMES SKINNER & COMPANY. 1899. EDINBURGH '. PRINTED BY JAMES SKINNER AND COMPANY. PREFATORY NOTE. This volume completes the Index to this Commissariot, so far as it is proposed by the Society to print the same. It includes all Testaments recorded before 31st December 1800. The remainder of the Record down to 31st December 1829 is in the General Register House, but from that date to the present day it will be found at the Commissary Office. The Register for the Eighteenth Century shows a considerable falling away in the number of Testaments recorded, due to some extent to the Local Registers being more taken advantage of On the other hand, a number of Testaments of Scotsmen dying in England, the Colonies, and abroad are to be found. The Register for the years following on the Union of the Parliaments is one of melancholy interest, containing as it does, to a certain extent, the death-roll of the ill-fated Darien Expedition. The ships of the Scottish Indian and African Company mentioned in " " " " the Record are the Caledonia," Rising Sun," Unicorn," Speedy " " " Return," Olive Branch," Duke of Hamilton (Walter Duncan, Skipper), " " " " Dolphin," St. Andrew," Hope," and Endeavour." ®Ij^ C0mmtssari0t ^ttoxi oi ®5tnburglj. REGISTER OF TESTAMENTS. THIRD SECTION—1701-180O. ••' Abdy, Sir Anthony Thomas, of Albyns, in Essex, Bart. -

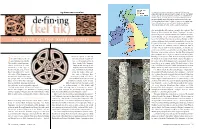

K 03-UP-004 Insular Io02(A)

By Bernard Wailes TOP: Seventh century A.D., peoples of Ireland and Britain, with places and areas that are mentioned in the text. BOTTOM: The Ogham stone now in St. Declan’s Cathedral at Ardmore, County Waterford, Ireland. Ogham, or Ogam, was a form of cipher writing based on the Latin alphabet and preserving the earliest-known form of the Irish language. Most Ogham inscriptions are commemorative (e.g., de•fin•ing X son of Y) and occur on stone pillars (as here) or on boulders. They date probably from the fourth to seventh centuries A.D. who arrived in the fifth century, occupied the southeast. The British (p-Celtic speakers; see “Celtic Languages”) formed a (kel´tik) series of kingdoms down the western side of Britain and over- seas in Brittany. The q-Celtic speaking Irish were established not only in Ireland but also in northwest Britain, a fifth- THE CASE OF THE INSULAR CELTS century settlement that eventually expanded to become the kingdom of Scotland. (The term Scot was used interchange- ably with Irish for centuries, but was eventually used to describe only the Irish in northern Britain.) North and east of the Scots, the Picts occupied the rest of northern Britain. We know from written evidence that the Picts interacted extensively with their neighbors, but we know little of their n decades past, archaeologists several are spoken to this day. language, for they left no texts. After their incorporation into in search of clues to the ori- Moreover, since the seventh cen- the kingdom of Scotland in the ninth century, they appear to i gin of ethnic groups like the tury A.D. -

The History of England A. F. Pollard

The History of England A study in political evolution A. F. Pollard, M.A., Litt.D. CONTENTS Chapter. I. The Foundations of England, 55 B.C.–A.D. 1066 II. The Submergence of England, 1066–1272 III. Emergence of the English People, 1272–1485 IV. The Progress of Nationalism, 1485–1603 V. The Struggle for Self-government, 1603–1815 VI. The Expansion of England, 1603–1815 VII. The Industrial Revolution VIII. A Century of Empire, 1815–1911 IX. English Democracy Chronological Table Bibliography Chapter I The Foundations of England 55 B.C.–A.D. 1066 "Ah, well," an American visitor is said to have soliloquized on the site of the battle of Hastings, "it is but a little island, and it has often been conquered." We have in these few pages to trace the evolution of a great empire, which has often conquered others, out of the little island which was often conquered itself. The mere incidents of this growth, which satisfied the childlike curiosity of earlier generations, hardly appeal to a public which is learning to look upon historical narrative not as a simple story, but as an interpretation of human development, and upon historical fact as the complex resultant of character and conditions; and introspective readers will look less for a list of facts and dates marking the milestones on this national march than for suggestions to explain the formation of the army, the spirit of its leaders and its men, the progress made, and the obstacles overcome. No solution of the problems presented by history will be complete until the knowledge of man is perfect; but we cannot approach the threshold of understanding without realizing that our national achievement has been the outcome of singular powers of assimilation, of adaptation to changing circumstances, and of elasticity of system. -

Ancient Foundations Marshall High School Unit Five AD * How the Irish Saved Civilization

The Dark Ages Marshall High School Mr. Cline Western Civilization I: Ancient Foundations Marshall High School Unit Five AD * How the Irish Saved Civilization • Christianity's Impact on Insular Art • Ireland's Golden Age is closely tied with the spread of Christianity. • As Angles and Saxons began colonizing the old Roman province of Brittania, Christians living in Britain fled to the relative safety of Ireland. • These Christians found themselves isolated from their neighbors on the mainland and essentially cut off from the influence of the Roman Catholic Church. • This isolation, combined with the mostly agrarian society of Ireland, resulted in a very different form of Christianity. • Instead of establishing a centralized hierarchy, like the Roman Catholic Church, Irish Christians established monasteries. • Monasticism got an early start in Ireland, and monasteries began springing up across the countryside. • The Irish did not just build monasteries in Ireland. * How the Irish Saved Civilization • Christianity's Impact on Insular Art • They sent missionaries to England to begin reconverting their heathen neighbors. • From there they crossed the channels, accelerating the conversion of France, Germany and the Netherlands and establishing monasteries from Poitiers to Vienna. • These monasteries became centers of art and learning, producing art of unprecedented complexity, like the Book of Kells, and great scholars, like the Venerable Bede (Yes, the guy who wrote the Anglo Saxon History of Britain was indeed Irish!) * How the Irish Saved Civilization • Christianity's Impact on Insular Art * How the Irish Saved Civilization • Christianity's Impact on Insular Art • Over time, Ireland became the cultural and religious leader of Northwestern Europe. -

THE SOUTH WEST SCOTLAND ELECTRICITY BOARD AREA Regional and Local Electricity Systems in Britain

DR. G.T. BLOOMFIELD Professor Emeritus, University of Guelph THE SOUTH WEST SCOTLAND ELECTRICITY BOARD AREA Regional and Local Electricity Systems in Britain 1 Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 2 The South West Scotland Electricity Board Area .......................................................................................... 2 Constituents of the South West Scotland Electricity Board ......................................................................... 3 Development of Electricity Supply Areas ...................................................................................................... 3 I Local Initiatives.................................................................................................................................. 6 II State Intervention ........................................................................................................................... 13 III Nationalisation ................................................................................................................................ 22 Summary ..................................................................................................................................................... 26 Note on Sources .......................................................................................................................................... 27 AYR Mill Street was an early AC station -

GOVERNING NORTH BRITAIN: RECENT STUDIES of SCOTTISH POLITICS Chris Allen Department of Politics University of Edinburgh C

GOVERNING NORTH BRITAIN: RECENT STUDIES OF SCOTTISH POLITICS Chris Allen Department of Politics University of Edinburgh C. Harvie No Gods and Precious Few Heroes: Scotland 1914- 80. London: Edward Arnold, 1981, 182pp W.L. Miller The End of British Politics? Scots and English Political Behaviour in the Seventies. Oxford: Clarendon, 1981, 28lpp J. Bochel,D. Denver, The Referendum Experience: Scotland 1979. & A. Macartney (eds.)Aberdeen: Aberdeen University Press, 198!, 210pp II.M. Drucker (ed.) John P. Mackintosh on Scotland. London: Longman, 1982, 232pp F. Beal<>y & The Politics of Independence: a Study of Scottish J. Sewel Town. Aberdeen: Aberdeen University Press, 1981, 272pp R .5. ~1oore The Social Impact of Oil: the Case of Peterhead. London: Routledge Kegan Paul, 1982, 189pp A.D. Smith The Ethnic Revival in the Modern World. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1981, 240pp C. H. Williams(ed.) National Separatism. Cardiff: University of Wales Press, 1982, 317pp. In the heady days of devolution and the zenith of nationalism, when Scotland for a moment ceased to be North Britain, books,theses and articles flowed out on Scottish politics. Most were on devolution and nationalism; many could barely be distinguished from each other, and all too few were of lasting worth. The flood abruptly ceased after 1979, but in the wake of the Referendum,work of much greater substance has begun to appear. These eight volumes are no less concerned with the old themes, but they handle them in a more scholarly and critical fashion, they are better documented and supported by extensive archi val and field work, and they help us - at least - to begin to answer many of the questions the older literature begged or evaded. -

TWO NATIONS? Regional Partisanship and Representation Fj at Westminster 1868-1983* Q

Scottish Government Yearbook 1985 Scottish Government Yearbook 1985 TWO NATIONS? Regional Partisanship and Representation fJ at Westminster 1868-1983* Q RMPUNNETI' READER IN POLITICS, UNIVERSITY OF STRATHCLYDE The 1979 and 1983 general elections seemed to confirm two popular assumptions about British electoral politics - that there is a distinct polarization between 'Tory' England and 'radical' Scotland and Wales, and that the size of England means that Conservative Governments are thrust upon unwilling Scots and Welsh by the English majority. Certainly, in 1979 the Conservatives won 59% of the seats in England and 53% in the United Kingdom as a whole, but won only 31% ofthe Scottish seats and 37% of the Welsh seats. Although Labour support in Scotland and Wales, as elsewhere in the United Kingdom, declined in 1983 as compared with 1979, Mrs Thatcher's 1983 'landslide' still left Labour with 57% of the seats in Scotland and 53% in Wales. Thus the immediate post-election reaction of The Scotsman in June 1983 was thatOl: "As usual, Scotland is distinctive and different...Here in Scotland it is the Conservative Party which has fallen below 30% of the vote ... how many Scots can believe that they are being fairly treated when they get a Government which has only 21 of the 72 Scottish MPs?" Similarly the Glasgow Herald observed that<2l: "The elections have confirmed a separate voting pattern in Scotland and have also made it more complicated ... 70% of the Scottish vote was for non-Government candidates, and almost by definition this must bring the Scottish dimension to the fore again." 30 31 ·Scottish Government Yearbook 1985 Scottish Government Yearbook 1985 twenty-nine elections from Gladstone's victory in 1868 to Mrs Thatcher's in But while the current partisan commitments of the component nations 1983.