The Botswana Kgotla System: a Mechanism for Traditional Conflict Resolution in Modern Botswana

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Botswana Guardian August 7, 2020 1

Botswana Guardian www.botswanaguardian.co.bw August 7, 2020 www.botswanaguardian.co.bw 1 Est. 1982 Fearless and Responsible ISSUE 4: Friday 7 AUGUST 2020 Alcohol industry jobs on the line p8 Botswana will send peace BDP in sixes troops on a and sevens need-to basis Ernest Moloi BG reporter Nicholas Mokwena Botswana will deploy troops BG reporter in peacekeeping missions only when there is “absolutely certain ember of positivity” that such effort will result Parliament in the promotion of a settlement, Mfor Jwaneng- President Dr. Mokgwetsi Masisi Mabutsane Mephato has said. Reatile has put his Masisi who is the incoming Chair party - Botswana of the SADC Organ on Defense, Democratic Party Politics and Security Cooperation (BDP) - in an told the media Wednesday evening awkward position. at State House 1 Gardens after a virtual Summit of the Organ Troika This follows his BDP MPs losing trust in Reatile plus Force Intervention Brigade- decision last week Troops Contributing Countries ‘VP and other senior party MPs not to vote with his (FIB-TCC) and the Democratic supported the motion so expectation colleagues for the Republic of Congo (DRC). was that Reatile will vote with us’ suspension Flanked by ministers Unity Dow I am a BDP member in good standing- SEE PAGE 6 and Kabo Morwaeng of Foreign Reatile SEE PAGE 5 LECHA LOAN #Areyeng BSB BotswanaBotswana Guardian Guardian 22 BGBGMARKETS MARKEts www.botswanaguardian.co.bw www.botswanaguardian.co.bw AugustAugust 7, 7, 2020 2020 Sefalana pays shareholders AbsaBotswana Guardian 2BG BGreporterMARKETS company annual financial statements. www.botswanaguardian.co.bw The divi- July 17, 2020 dend will be paid around the 25 th of August 200 appoint Sefalana group last week announced that the to shareholders registered by 14 th of the same board of directors ETFhas approved trading 27.5 thebe per up month. -

The Case of the Zezuru Informal Economy in Botswana

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Kyoto University Research Information Repository DEVELOPMENT POLICY AND ETHNIC EXCLUSION : Title THE CASE OF THE ZEZURU INFORMAL ECONOMY IN BOTSWANA Author(s) GWATIWA, Tshepo T. Citation African Study Monographs (2014), 35(2): 65-84 Issue Date 2014-06 URL http://dx.doi.org/10.14989/189521 Right Type Departmental Bulletin Paper Textversion publisher Kyoto University African Study Monographs, 35(2): 65–84, June 2014 65 DEVELOPMENT POLICY AND ETHNIC EXCLUSION: THE CASE OF THE ZEZURU INFORMAL ECONOMY IN BOTSWANA Tshepo T. GWATIWA Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies, Geneva ABSTRACT This article discusses Botswana’s development policies and its silent exclusion of minority groups, particularly the Zezuru. Focusing on the case of the Zezuru, the paper seeks to demonstrate that historical ethnic discrimination and exclusion has blinded the government’s economic diversification strategy. It draws a parallel between government policies and negligence in particular projects that fall within the scope of the diversification strategy. It discusses the government’s failure to engage the Zezuru into modernizing their informal economy. It also discusses the lack of Zezuru access to the venture capital provided by government meant to improve the formal economy. It looks into the fiscal risks and lost benefits to the government while the Zezuru informal economy remains strong. The author conclusively argues that the economic exclusion of the Zezuru in development policy implementation is a setback in the overall diversification strategy. Key Words: Botswana; Zezuru; Socioeconomic exclusion; Informal economy. INTRODUCTION Botswana is a democratic middle-income state located at the heart of the South- ern African Development Community (SADC). -

Performance of Goats and Sheep Under Communal Grazing in Botswana Using Various Growth Measures

B07 Performance of goats and sheep under communal grazing in Botswana using various growth measures L. Baleseng, O. E Kgosikoma, A. Makgekgenene | Department of Agricultural Research, Private | Gaborone | Botswana M. Coleman, P. Morley | Institute for Rural Futures, School of Behavioural, Cognitive and Social Sciences, University of New England | Armidale | Australia D. Baker, O. | UNE Business School, University of New England | Armidale | Australia S. Bahta | International Livestock Research Institute | Nairobi | Kenya DOI: 10.1481/icasVII.2016.b07 ABSTRACT We conducted a survey to evaluate the growth of goats and sheep under communal grazing, and to determine the relationship between weight, heart girth, shoulder height, and body condition score in Kweneng, Central and Kgalagadi districts, Botswana. The same animals were measured on two separate occasions, approximately one month apart, to allow growth rates to be recorded. Significant differences in growth rates between the three case study districts were found for both goats and sheep. Amongst the goats measured, gains in height and weight were significantly greater in the Kweneng district, while gains in heart girth measurement were greatest in the Central district. In the case of sheep, weight gain was significantly higher in the Central and Kgalagadi districts, increases in girth measurement were significantly higher in the Central district, and shoulder height gain was significantly greater in the Kweneng district. Statistical tests were used to determine the relationships between animal weight and the other measures taken for goats and sheep. Heart girth in both goats and sheep was shown to be a significant predictor of weight across all three districts. Likewise, shoulder height proved to be a statistically significant predictor of animal weight for both goats and sheep, across each district. -

Botswana Environment Statistics Water Digest 2018

Botswana Environment Statistics Water Digest 2018 Private Bag 0024 Gaborone TOLL FREE NUMBER: 0800600200 Tel: ( +267) 367 1300 Fax: ( +267) 395 2201 E-mail: [email protected] Website: http://www.statsbots.org.bw Published by STATISTICS BOTSWANA Private Bag 0024, Gaborone Phone: 3671300 Fax: 3952201 Email: [email protected] Website: www.statsbots.org.bw Contact Unit: Environment Statistics Unit Phone: 367 1300 ISBN: 978-99968-482-3-0 (e-book) Copyright © Statistics Botswana 2020 No part of this information shall be reproduced, stored in a Retrieval system, or even transmitted in any form or by any means, whether electronically, mechanically, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of Statistics Botswana. BOTSWANA ENVIRONMENT STATISTICS WATER DIGEST 2018 Statistics Botswana PREFACE This is Statistics Botswana’s annual Botswana Environment Statistics: Water Digest. It is the first solely water statistics annual digest. This Digest will provide data for use by decision-makers in water management and development and provide tools for the monitoring of trends in water statistics. The indicators in this report cover data on dam levels, water production, billed water consumption, non-revenue water, and water supplied to mines. It is envisaged that coverage of indicators will be expanded as more data becomes available. International standards and guidelines were followed in the compilation of this report. The United Nations Framework for the Development of Environment Statistics (UNFDES) and the United Nations International Recommendations for Water Statistics were particularly useful guidelines. The data collected herein will feed into the UN System of Environmental Economic Accounting (SEEA) for water and hence facilitate an informed management of water resources. -

Traditional Leadership: Some Reflections on Morphology of Constitutionalism and Politics of Democracy in Botswana

International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Vol. 1 No. 14; October 2011 TRADITIONAL LEADERSHIP: SOME REFLECTIONS ON MORPHOLOGY OF CONSTITUTIONALISM AND POLITICS OF DEMOCRACY IN BOTSWANA Dr Khunou Samuelson Freddie 1. INTRODUCTION An objective analysis of constitutional model of Botswana has a start from the colonial era within the political relations among the Tswana politicians, traditional leaders and the representatives of the Great Britain. This article seeks to discuss the role of the traditional leaders and politicians in the constitutional construction of Botswana with specific reference to both the 1965 and 1966 constitutions. With the advent of constitutionalism and democracy in Botswana, the role of the institution of traditional leadership was redefined. The constitutional dispensation had a profound impact on the institution of traditional leadership in Botswana and seemingly made serious inroads in the institution by altering the functions, which traditional leaders had during the pre-colonial and colonial periods. For example, constitutional institution such as the National House of Chiefs was established to work closely with the central government on matters of administration particularly those closely related to traditional communities, traditions and customs. This article will also explore and discuss the provisions of both the 1965 and 1966 Constitutions of Botswana and established how they affected the roles, functions and powers of traditional leaders in Botswana. 2. TOWARDS THE CONSTITUTIONAL CONSTRUCTION For many African countries, the year 1960 was the annus mirabilis in which most of them attained independence. Botswana also took an important step towards self-government in the early sixties. In 1959 a Committee of the Joint Advisory Council (JAC) presented a report recommending that this Council should be reconstituted as Legislative Council (LC). -

Populated Printable COP 2009 Botswana Generated 9/28/2009 12:01:26 AM

Populated Printable COP 2009 Botswana Generated 9/28/2009 12:01:26 AM ***pages: 415*** Botswana Page 1 Table 1: Overview Executive Summary None uploaded. Country Program Strategic Overview Will you be submitting changes to your country's 5-Year Strategy this year? If so, please briefly describe the changes you will be submitting. X Yes No Description: test Ambassador Letter File Name Content Type Date Uploaded Description Uploaded By Letter from Ambassador application/pdf 11/14/2008 TSukalac Nolan.pdf Country Contacts Contact Type First Name Last Name Title Email PEPFAR Coordinator Thierry Roels Associate Director GAP-Botswana [email protected] DOD In-Country Contact Chris Wyatt Chief, Office of Security [email protected] Cooperation HHS/CDC In-Country Contact Thierry Roels Associate Director GAP-Botswana [email protected] Peace Corps In-Country Peggy McClure Director [email protected] Contact USAID In-Country Contact Joan LaRosa USAID Director [email protected] U.S. Embassy In-Country Phillip Druin DCM [email protected] Contact Global Fund In-Country Batho C Molomo Coordinator of NACA [email protected] Representative Global Fund What is the planned funding for Global Fund Technical Assistance in FY 2009? $0 Does the USG assist GFATM proposal writing? Yes Does the USG participate on the CCM? Yes Generated 9/28/2009 12:01:26 AM ***pages: 415*** Botswana Page 2 Table 2: Prevention, Care, and Treatment Targets 2.1 Targets for Reporting Period Ending September 30, 2009 National 2-7-10 USG USG Upstream USG Total Target Downstream (Indirect) -

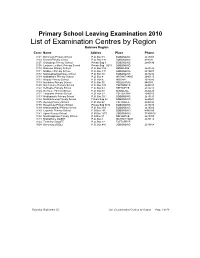

List of Examination Centres by Region Bobirwa Region Centr Name Addres Place Phone 0101 Bobonong Primary School P.O

Primary School Leaving Examination 2010 List of Examination Centres by Region Bobirwa Region Centr Name Addres Place Phone 0101 Bobonong Primary School P.O. Box 48 BOBONONG 2619207 0103 Borotsi Primary School P.O. Box 136 BOBONONG 819208 0107 Gobojango Primary School Private Bag 8 BOBONONG 2645436 0108 Lentswe-Le-Moriti Primary School Private Bag 0019 BOBONONG 0110 Mabolwe Primary School P.O. Box 182 SEMOLALE 2645422 0111 Madikwe Primary School P.O. Box 131 BOBONONG 2619221 0112 Mafetsakgang primary school P.O. Box 46 BOBONONG 2619232 0114 Mathathane Primary School P.O. Box 4 MATHATHANE 2645110 0117 Mogapi Primary School P.O. Box 6 MOGAPI 2618545 0119 Molalatau Primary School P.O. Box 50 MOLALATAU 845374 0120 Moletemane Primary School P.O. Box 176 TSETSEBYE 2646035 0123 Sefhophe Primary School P.O. Box 41 SEFHOPHE 2618210 0124 Semolale Primary School P.O. Box 10 SEMOLALE 2645422 0131 Tsetsejwe Primary School P.O. Box 33 TSETSEJWE 2646103 0133 Modisaotsile Primary School P.O. Box 591 BOBONONG 2619123 0134 Motlhabaneng Primary School Private Bag 20 BOBONONG 2645541 0135 Busang Primary School P.O. Box 47 TSETSEBJE 2646144 0138 Rasetimela Primary School Private Bag 0014 BOBONONG 2619485 0139 Mabumahibidu Primary School P.O. Box 168 BOBONONG 2619040 0140 Lepokole Primary School P O Box 148 BOBONONG 4900035 0141 Agosi Primary School P O Box 1673 BOBONONG 71868614 0142 Motsholapheko Primary School P O Box 37 SEFHOPHE 2618305 0143 Mathathane DOSET P.O. Box 4 MATHATHANE 2645110 0144 Tsetsebye DOSET P.O. Box 33 TSETSEBYE 3024 Bobonong DOSET P.O. Box 483 BOBONONG 2619164 Saturday, September 25, List of Examination Centres by Region Page 1 of 39 Boteti Region Centr Name Addres Place Phone 0201 Adult Education Private Bag 1 ORAPA 0202 Baipidi Primary School P.O. -

The Republic of Botswana Second and Third Report To

THE REPUBLIC OF BOTSWANA SECOND AND THIRD REPORT TO THE AFRICAN COMMISSION ON HUMAN AND PEOPLES' RIGHTS (ACHPR) IMPLEMENTATION OF THE AFRICAN CHARTER ON HUMAN AND PEOPLES’ RIGHTS 2015 1 | P a g e TABLE OF CONTENTS I. PART I. a. Abbreviations b. Introduction c. Methodology and Consultation Process II. PART II. A. General Information - B. Laws, policies and (institutional) mechanisms for human rights C. Follow-up to the 2010 Concluding observations D. Obstacles to the exercise and enjoyment of the rights and liberties enshrined in the African Charter: III. PART III A. Areas where Botswana has made significant progress in the realization of the rights and liberties enshrined in the African Charter a. Article 2, 3 and 19 (Non-discrimination and Equality) b. Article 7 & 26 (Fair trial, Independence of the Judiciary) c. Article 10 (Right to association) d. Article 14 (Property) e. Article 16 (Health) f. Article 17 (Education) g. Article 24 (Environment) B. Areas where some progress has been made by Botswana in the realization of the rights and liberties enshrined in the African Charter a. Article 1er (implementation of the provisions of the African Charter) b. Article 4 (Life and Integrity of the person) c. Article 5 (Human dignity/Torture) d. Article 9 (Freedom of Information) e. Article 11 (Freedom of Assembly) f. Article 12 (Freedom of movement) g. Article 13 (participation to public affairs) h. Article 15 (Work) i. Article 18 (Family) j. Article 20 (Right to existence) k. Article 21 (Right to freely dispose of wealth and natural resources) 2 | P a g e C. -

اجلمعية العامة Arabic Original: English

اﻷمم املقحدة A/HRC/40/64/Add.2 Distr.: General 9 January 2019 اجلمعية العامة Arabic Original: English جملس حقوق اﻹنسان الدورة اﻷربعون 25 شباط/فرباير - 22 آذار/مارس 2019 البند 3 من جدول اﻷعمال تعزيز ومحاية مجيع حقوق اﻹنسان، املدنية والسياسية واﻻقتصادية واﻻجتماعية والثقافية، مبا يف ذلك احلق يف التنمية زايرة بوتسواان تقرير املقرر اخلاص املعين بقضااي اﻷقليات موجز زار املقرر اخلاص املعين بقضااي اﻷقليات، فريانن دو فارين، بوتسواان يف الفرتة من 12 إىل 2٤ آب/أغسطس 201٨ للنظر فيما هو معمول به من تشريعات وسياسات وممارسات حلمايةةو وتعزيةةز قةةوا اﻷشةةماص املنقمةةت إىل أقليةةات قوميةةو أو إأنيةةو أو دينيةةو أو ل ويةةةو، وﻻ سيما فيما يقعلق ابحلصول على القعليم اجليد وعلى الرعايو الصحيو وغريها من اخلدمات العامةةو، واسةةةقمدال اﻷقليةةةات لل ايةةةا، وملويةةةو اﻷرااةةا واحلصةةةول علةةةى املةةةوارد، ومشةةةار و اﻷقليات يف احلياة السياسيو، واجلهود الراميو إىل موافحو خطاب الوراهيةو ويسةلا املقةرر اخلةاص الضةو ، يف تقريةةر عةن زايرتةةه بوتسةواان، علةى القةةدابري ااختابيةو الةة ا ة يا وومةةو بوتسواان ﻻ رتال قوا اﻷقليات القوميو ااأنيو والدينيو والل ويو ويقدل املقرر اخلاص عددا من القوصيات هبدف مساعدة احلوومو وغريها من اجلهات الفاعلو املعنيو يف جهودها الراميو إىل ت ليل العقبات ال تعرتض سبيل إعمال قوا اانسان لﻷقليات يف بوتسواان __________ * يعَّمم موجز الققريةر مميةا الل ةات الر.يةو أمةا الققريةر نفسةه، الةوارد يف مرفةق هة ا املةوجز، فةيلعمم ابلل ةو الة قةل دل هبا فقا GE.19-00324(A) A/HRC/40/64/Add.2 Annex Report of the Special Rapporteur on minority issues on his visit to Botswana Contents Page I. Introduction......................................................................................................................................... 3 II. Visit objectives ................................................................................................................................... 3 III. General context ................................................................................................................................... 3 IV. -

The Parliamentary Constituency Offices

REPUBLIC OF BOTSWANA THE PARLIAMENTARY CONSTITUENCY OFFICES Parliament of Botswana P O Box 240 Gaborone Tel: 3616800 Fax: 3913103 Toll Free; 0800 600 927 e - mail: [email protected] www.parliament.gov.bw Introduction Mmathethe-Molapowabojang Mochudi East Mochudi West P O Box 101 Mmathethe P O Box 2397 Mochudi P O Box 201951 Ntshinoge Representative democracy can only function effectively if the Members of Tel: 5400251 Fax: 5400080 Tel: 5749411 Fax: 5749989 Tel: 5777084 Fax: 57777943 Parliament are accessible, responsive and accountable to their constituents. Mogoditshane Molepolole North Molepolole South The mandate of a Constituency Office is to act as an extension of Parliament P/Bag 008 Mogoditshane P O Box 449 Molepolole P O Box 3573 Molepolole at constituency level. They exist to play this very important role of bringing Tel: 3915826 Fax: 3165803 Tel: 5921099 Fax: 5920074 Tel: 3931785 Fax: 3931785 Parliament and Members of Parliament close to the communities they serve. Moshupa-Manyana Nata-Gweta Ngami A constituency office is a Parliamentary office located at the headquarters of P O Box 1105 Moshupa P/Bag 27 Sowa Town P/Bag 2 Sehithwa Tel: 5448140 Fax: 5448139 Tel: 6213756 Fax: 6213240 Tel: 6872105/123 each constituency for use by a Member of Parliament (MP) to carry out his or Fax: 6872106 her Parliamentary work in the constituency. It is a formal and politically neutral Nkange Okavango Palapye place where a Member of Parliament and constituents can meet and discuss P/Bag 3 Tutume P O Box 69 Shakawe P O Box 10582 Palapye developmental issues. Tel: 2987717 Fax: 2987293 Tel: 6875257/230 Tel: 4923475 Fax: 4924231 Fax: 6875258 The offices must be treated strictly as Parliamentary offices and must therefore Ramotswa Sefhare-Ramokgonami Selibe Phikwe East be used for Parliamentary business and not political party business. -

Securing Recognition of Minorities and Maginalized People and Their Rights in Botswana

Evaluation: Securing Recognition of Minorities and Marginalized People and their Rights in Botswana PROJECT EVALUATION REPORT FINAL SECURING RECOGNITION OF MINORITIES AND MAGINALIZED PEOPLE AND THEIR RIGHTS IN BOTSWANA Submitted to: Minorities Rights Group International, 54 Commercial Street, London E1, 6LT, United Kingdom Submitted by: Tersara Investments P.O. Box 2139, Gaborone, Botswana, Africa 2/27/2019 This document is property of Minorities Rights Group International, a registered UK Charity and Company Limited by Guarantee and its Partners. 1 Evaluation: Securing Recognition of Minorities and Marginalized People and their Rights in Botswana Document details Client Minority Rights Group International Project title Consulting Services for the Final Evaluation: Securing Recognition of Minorities and Marginalized Peoples and their Rights in Botswana Document type Final Evaluation Document No. TS/18/MRG/EVAL00 This document Text (pgs.) Tables (No.) Figures (no.) Annexes Others comprises 17 3 7 2 N/A Document control Document version Detail Issue date TS/19/MRG/EVAL01 Project Evaluation Report FINAL for 13 June 2019 MRGI 2 Evaluation: Securing Recognition of Minorities and Marginalized People and their Rights in Botswana Contents Document details ..................................................................................... Error! Bookmark not defined. Document control ................................................................................................................................... 2 LIST OF FIGURES (TABLES, CHARTS) -

Land Tenure Reforms and Social Transformation in Botswana: Implications for Urbanization

Land Tenure Reforms and Social Transformation in Botswana: Implications for Urbanization. Item Type text; Electronic Dissertation Authors Ijagbemi, Bayo, 1963- Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 06/10/2021 17:13:55 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/196133 LAND TENURE REFORMS AND SOCIAL TRANSFORMATION IN BOTSWANA: IMPLICATIONS FOR URBANIZATION by Bayo Ijagbemi ____________________ Copyright © Bayo Ijagbemi 2006 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF ANTHROPOLOGY In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2006 2 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE As members of the Dissertation Committee, we certify that we have read the dissertation prepared by Bayo Ijagbemi entitled “Land Reforms and Social Transformation in Botswana: Implications for Urbanization” and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy _______________________________________________________________________ Date: 10 November 2006 Dr Thomas Park _______________________________________________________________________ Date: 10 November 2006 Dr Stephen Lansing _______________________________________________________________________ Date: 10 November 2006 Dr David Killick _______________________________________________________________________ Date: 10 November 2006 Dr Mamadou Baro Final approval and acceptance of this dissertation is contingent upon the candidate’s submission of the final copies of the dissertation to the Graduate College. I hereby certify that I have read this dissertation prepared under my direction and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement.