Kiranti Languages Boyd Michailovsky

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Deixis and Reference Tracing in Tsova-Tush (PDF)

DEIXIS AND REFERENCE TRACKING IN TSOVA-TUSH A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAIʻI AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN LINGUISTICS MAY 2020 by Bryn Hauk Dissertation committee: Andrea Berez-Kroeker, Chairperson Alice C. Harris Bradley McDonnell James N. Collins Ashley Maynard Acknowledgments I should not have been able to finish this dissertation. In the course of my graduate studies, enough obstacles have sprung up in my path that the odds would have predicted something other than a successful completion of my degree. The fact that I made it to this point is a testament to thekind, supportive, wise, and generous people who have picked me up and dusted me off after every pothole. Forgive me: these thank-yous are going to get very sappy. First and foremost, I would like to thank my Tsova-Tush host family—Rezo Orbetishvili, Nisa Baxtarishvili, and of course Tamar and Lasha—for letting me join your family every summer forthe past four years. Your time, your patience, your expertise, your hospitality, your sense of humor, your lovingly prepared meals and generously poured wine—these were the building blocks that supported all of my research whims. My sincerest gratitude also goes to Dantes Echishvili, Revaz Shankishvili, and to all my hosts and friends in Zemo Alvani. It is possible to translate ‘thank you’ as მადელ შუნ, but you have taught me that gratitude is better expressed with actions than with set phrases, sofor now I will just say, ღაზიშ ხილჰათ, ბედნიერ ხილჰათ, მარშმაკიშ ხილჰათ.. -

Chapter 6 Morphological Split

Chapter 6 Morphological Split Chapter 6 Morphological Split: Accusative Behaviour of Pronouns As mentioned in the previous chapters, Tongan shows a morphological split based on types of nouns. Specifically, full NP’s are divided into ERG and ABS, while pronouns show an accusative pattern: S and A appear as a subject pronoun, while O is realised in a distinct form. We will argue, however, that the accusative pattern does not mean that the pronouns receive NOM in the subject position and ACC in the object position. Rather, it is due to the fact that pronominal subjects are realised as clitics in Tongan. We will argue that the form of a subject clitic reflects the theta-role it bears and not the case. In particular, we will argue that despite the identical phonological form, a subject clitic receives ERG when it refers to A, and ABS when it refers to S. In §6.1, we will look at the data that demonstrate the apparent accusative pattern, which Tongan pronouns show. Our data demonstrate another peculiar property of the Tongan pronouns, namely, the compulsory word order alternation. In §6.2, we will argue that the SVO order results from the fact that the subject pronouns are clitics attached to T. We will also argue that object pronouns are full pronouns. Object clitics are not part of the lexical inventory of Tongan. In §6.3, we will develop the hypothesis that the subject clitics in Tongan are theta-role absorbers in the sense of Aoun (1985) and therefore, are arguments. This hypothesis explains why the pronouns in Tongan show an accusative pattern. -

Himalayan Linguistics a Free Refereed Web Journal and Archive Devoted to the Study of the Languages of the Himalayas

himalayan linguistics A free refereed web journal and archive devoted to the study of the languages of the Himalayas Himalayan Linguistics Issues in Bahing orthography development Maureen Lee CNAS; SIL abstract Section 1 of this paper summarizes the community-based process of Bahing orthography development. Section 2 introduces the criteria used by the Bahing community members in deciding how Bahing sounds should be represented in the proposed Bahing orthography with Devanagari used as the script. This is followed by several sub-sections which present some of the issues involved in decision-making, the decisions made, and the rationale for these decisions for the proposed Bahing Devanagari orthography: Section 2.1 mentions the deletion of redundant Nepali Devanagari letters for the Bahing orthography; Section 2.2 discusses the introduction of new letters to represent Bahing sounds that do not exist in Nepali or are not distinctively represented in the Nepali Alphabet; Section 2.3 discusses the omission of certain dialectal Bahing sounds in the proposed Bahing orthography; and Section 2.4 discusses various length related issues. keywords Kiranti, Bahing language, Bahing orthography, orthography development, community-based orthography development This is a contribution from Himalayan Linguistics, Vol. 10(1) [Special Issue in Memory of Michael Noonan and David Watters]: 227–252. ISSN 1544-7502 © 2011. All rights reserved. This Portable Document Format (PDF) file may not be altered in any way. Tables of contents, abstracts, and submission guidelines are available at www.linguistics.ucsb.edu/HimalayanLinguistics Himalayan Linguistics, Vol. 10(1). © Himalayan Linguistics 2011 ISSN 1544-7502 Issues in Bahing orthography development Maureen Lee CNAS; SIL 1 Introduction 1.1 The Bahing language and speakers Bahing (Bayung) is a Tibeto-Burman Western Kirati language, with the traditional homelands of their speakers spanning the hilly terrains of the southern tip of Solumkhumbu District and the eastern part of Okhaldhunga District in eastern Nepal. -

Gender Equality and Social Inclusion Diagnostic of Selected Sectors in Nepal

GENDER EQUALITY AND SOCIAL INCLUSION DIAGNOSTIC OF SELECTED SECTORS IN NEPAL OCTOBER 2020 ASIAN DEVELOPMENT BANK GENDER EQUALITY AND SOCIAL INCLUSION DIAGNOSTIC OF SELECTED SECTORS IN NEPAL OCTOBER 2020 ASIAN DEVELOPMENT BANK Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 IGO license (CC BY 3.0 IGO) © 2020 Asian Development Bank 6 ADB Avenue, Mandaluyong City, 1550 Metro Manila, Philippines Tel +63 2 8632 4444; Fax +63 2 8636 2444 www.adb.org Some rights reserved. Published in 2020. ISBN 978-92-9262-424-8 (print); 978-92-9262-425-5 (electronic); 978-92-9262-426-2 (ebook) Publication Stock No. TCS200291-2 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.22617/TCS200291-2 The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views and policies of the Asian Development Bank (ADB) or its Board of Governors or the governments they represent. ADB does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this publication and accepts no responsibility for any consequence of their use. The mention of specific companies or products of manufacturers does not imply that they are endorsed or recommended by ADB in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. By making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area, or by using the term “country” in this document, ADB does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. This work is available under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 IGO license (CC BY 3.0 IGO) https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/igo/. -

Two Reflexive Markers in Slavic

Russ Linguist (2010) 34: 203–238 DOI 10.1007/s11185-010-9062-7 Two reflexive markers in Slavic Два маркера возвратности в славянских языках Dorothee Fehrmann · Uwe Junghanns · Denisa Lenertova´ Published online: 22 September 2010 © The Author(s) 2010. This article is published with open access at Springerlink.com Abstract The paper deals with lexical types of the reflexive marker in Slavic. On the one hand, this exponent shows up in a range of expressions associated with diverse in- terpretations. On the other hand, the properties within the various types are not homo- geneous across the Slavic languages. The challenge consists in finding a unified analysis for the constructions and their varying properties, accounting for the marker with as few construction-specific assumptions as possible. In this paper, we will argue that two lexical types of the reflexive marker—argument blocking and argument binding—are sufficient to cover all constructions and their cross-Slavic variation. Аннотация Данная статья посвящена лексическим типам маркера возвратности в славянских языках. Этот маркер употребляется в предложениях разного типа, свя- занных с рядом интерпретаций. Однако, выясняется, что свойства отдельных типов в славянских языках не гомогенные. Задача состоит в том, чтобы разработать мак- The research is part of the project ‘Microtypological variation in argument structure and morphosyntax’ funded by the German Research Foundation (research group FOR 742 ‘Grammar and Processing of Verbal Arguments’ at the University of Leipzig). Thanks are due to Hagen Pitsch who participated in the initial discussion and data elicitation. Earlier versions of the paper have been presented at the Workshop ‘Macrofunctionality and Underspecification’ in Wittenberg (August 2009), the Fourth Annual Meeting of the Slavic Linguistics Society in Zadar (September 2009), the Workshop ‘Verbargumente in Semantik und Syntax’ in Göttingen (January 2010), and the ‘Workshop on Slavic Syntax and Semantics’ at the 33rd GLOW Colloquium in Wrocław (April 2010). -

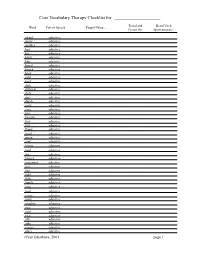

250 Word List

Core Vocabulary Therapy Checklist for ____________________ Tested and Heard Used Word Part of Speech Taught Using ... Passed On: Spontaneously: afraid adjective angry adjective another adjective bad adjective big adjective black adjective blue adjective bored adjective brown adjective busy adjective cold adjective cool adjective dark adjective different adjective dirty adjective dry adjective dumb adjective early adjective easy adjective fast adjective favorite adjective first adjective full adjective funny adjective good adjective green adjective grey adjective happy adjective hard adjective hot adjective hungry adjective important adjective last adjective late adjective light adjective little adjective lonely adjective long adjective mad adjective many adjective more adjective naughty adjective new adjective next adjective nice adjective old adjective only adjective orange adjective other adjective ©VanTatenhove, 2001 page 1 Core Vocabulary Therapy Checklist for ____________________ Word Part of Speech Taught Using ... Tested and Heard Used Passed On: Spontaneously: pink adjective purple adjective real adjective red adjective right adjective sad adjective same adjective sick adjective silly adjective sure adjective thirsty adjective tired adjective wet adjective white adjective wrong adjective yellow adjective adjective adjective adjective again adverb all right adverb almost adverb already adverb always adverb away adverb backwards adverb forward adverb here adverb indoors adverb just adverb maybe adverb much adverb never adverb not -

Gustar Verbs, Unaccusatives and the Impersonal Passive

ISSN 1798-4769 Journal of Language Teaching and Research, Vol. 3, No. 2, pp. 321-330, March 2012 © 2012 ACADEMY PUBLISHER Manufactured in Finland. doi:10.4304/jltr.3.2.321-330 Teaching Subject Position in Spanish: Gustar Verbs, Unaccusatives and the Impersonal Passive Roberto Mayoral Hernández University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, USA Email: [email protected] Abstract—This paper explores a misunderstood and frequently ignored topic in the literature dealing with teaching Spanish as an L2: subject position (Vanpatten & Cadierno, 1993). Native speakers of English, and other languages whose subjects have a fixed position in the sentence, find it difficult to acquire the patterns that govern subject placement in Spanish, which may either precede or follow the verb. This difficulty is due in part to cross-linguistic differences associated to the argument structure of certain expressions, but it is also caused by the inadequate treatment of this topic in many textbooks and dictionaries. Subject inversion, i.e. the placement of the subject in postverbal position, is not a random phenomenon, and its occurrence is often limited to specific constructions. This paper examines three structures that are frequently associated with postverbal subjects: verbs of psychological affection, the impersonal passive and unaccusative verbs. Several communicative task-based activities are also presented, in order to ensure that L2 learners of Spanish are able to recognize postverbal subjects as a common phenomenon. Index Terms—unaccusative verbs, impersonal passive, subject position, Spanish, verbs of psychological affection I. INTRODUCTION The variable position of the subject argument in Spanish is a largely ignored topic in textbooks and grammars for learners of Spanish as a non-native language. -

Problems in Bantawa Phonology and a Statistically Driven Approach to Vowels1 Rachel Vogel

Problems in Bantawa Phonology and a Statistically Driven Approach to Vowels1 Rachel Vogel A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts in Linguistics Swarthmore College December 2015 Abstract This thesis examines several aspects of the phonology of Bantawa, an endangered and fairly understudied Tibeto-Burman language of N epa!. I provide a brief review of the major literature on Bantawa to date and discuss two particular phonological controversies: one concerning the presence of retroflex consonants, and one concerning the vowel inventory, specifically whether there are six or seven vowel phonemes. I draw on data I recorded from a native speaker to address each of these issues. With regard to the latter, I also provide an in-depth acoustic analysis of my consultant's 477 vowels and consider several types of statistical models to help address the issue of the number of vowel contrasts. My main conclusions, based on the data from my consultant, are first, that there is evidence based on minimal pairs for a contrast between retroflex and alveolar stops, and second, that there is no clear evidence for a seven-vowel system in Bantawa. With regard to the latter point, additional avenues of research would still be needed to explore the possibility of allophonic variation and/or individual speaker differences. L Introduction There are over 120 languages spoken throughout Nepal, representing four different language families (Lewis et al. 2014; Ghimire 2013). Due to the lasting effects of a long history of social, political, and economic pressures, however, many of these languages are now endangered (Toba et al. -

Sino-Tibetan Languages 393

Sino-Tibetan Languages 393 Gair J W (1998). Studies in South Asian linguistics: Sinhala Government Press. [Reprinted Sri Lanka Sahitya and other South Asian languages. Oxford: Oxford Uni- Mandalaya, Colombo: 1962.] versity Press. Karunatillake W S (1992). An introduction to spoken Sin- Gair J W & Karunatillake W S (1974). Literary Sinhala. hala. Colombo: Gunasena. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University South Asia Program. Karunatillake W S (2001). Historical phonology of Sinha- Gair J W & Karunatillake W S (1976). Literary Sinhala lese: from old Indo-Aryan to the 14th century AD. inflected forms: a synopsis with a transliteration guide to Colombo: S. Godage and Brothers. Sinhala script. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University South Asia Macdougall B G (1979). Sinhala: basic course. Program. Washington D.C.: Foreign Service Institute, Department Gair J W & Paolillo J C (1997). Sinhala (Languages of the of State. world/materials 34). Mu¨ nchen: Lincom. Matzel K & Jayawardena-Moser P (2001). Singhalesisch: Gair J W, Karunatillake W S & Paolillo J C (1987). Read- Eine Einfu¨ hrung. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz. ings in colloquial Sinhala. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Reynolds C H B (ed.) (1970). An anthology of Sinhalese South Asia Program. literature up to 1815. London: George Allen and Unwin Geiger W (1938). A grammar of the Sinhalese language. (English translations). Colombo: Royal Asiatic Society. Reynolds C H B (ed.) (1987). An anthology of Sinhalese Godakumbura C E (1955). Sinhalese literature. Colombo: literature of the twentieth century. Woodchurch, Kent: Colombo Apothecaries Ltd. Paul Norbury/Unesco (English translations). Gunasekara A M (1891). A grammar of the Sinhalese Reynolds C H B (1995). Sinhalese: an introductory course language. -

Of Nepal UPR Working Group of the Human Rights Council 23Rd Session

Annex-2 Words: 5482 Marginalized Groups' Joint Submission to the United Nations Universal Periodic Review (UPR) of Nepal UPR Working Group of the Human Rights Council 23rd Session Submitted by DURBAN REVIEW CONFERENCE FOLLOW-UP COMMITTEE (DRCFC) Jana Utthhan Pratisthan (JUP), Secretariat for the DRCFC, dedicated to promotion and protection of the Human Rights of Dalit. JUP has Special Consultative Status with United Nations Economic and Social Council 20th March 2015 Nepal I. INTRODUCTION AND METHODOLOGY 1. This stakeholders' report is a joint submission of Durban Review Follow-up Committee (DRCFC), founded in 2009. DRCFC is a network working for protection and promotion of human rights of various marginalized groups of Nepal, namely: Dalit, Indigenous Peoples, Freed bonded laborers, Sexual and Gender minorities, Persons with Disability, Muslim and Religious minorities and Madhesis. 2. This report presents implementation status of UPR 2011 recommendations, and highlights major emerging themes of concerns regarding the human rights of the various vulnerable groups. This report is the outcome of an intensive consultation processes undertaken from October 2014 to January 2015 in regional and national basis. During this period, DRCFC conducted six regional consultations with the members of marginalized groups in five development regions and eight thematic and national consultation meetings at national level. In these consultations processes, nearly 682 representatives of 68 organizations attended and provided valuable information for this report (Annex-A). II. BACKGROUND AND FRAMEWORK 2.1. Scope of International Obligations 3. To ensure full compliance with international human rights standards, Nepal accepted recommendation (108:11)1 as a commitment to review and adopt relevant legislation and policies. -

No Registration No Name Industry 1 10100003 RAI YOGENDRA

ममति २०७५ जेष्ठ २६ र २७ गि े मऱइएको नवौ कोररयन भाषा (EPS-TOPIK) परीऺामा सहभागी भएका तन륍न मऱखिि परीऺार्थीह셁 देहाय बमोजजम ऺेत्रका ऱागग उत्तिर्ण भएको ब्यहोरा HRD Korea बाट प्राप्ि भएकोऱे स륍बजधिि सबैको जानकारीको ऱागग यो सचना प्रकामिि गरीएको छ । उत्तिर्ण भएका ब्यजतिह셁को बबवरर् यस कायाणऱयको वेवसाइट , ू , , www.epsnepal.gov.np यस कायाणऱयको सूचनापाटी वैदेमिक रोजगार त्तवभागको वेभसाइट www.dofe.gov.np श्रम िर्था www.mole.gov.np HRD Korea www.eps.go.kr रोजगार मधत्राऱयको वेवसाइट र , को वेवसाइट बाट समेि हेन ण सककने छ । भाषा परीऺा उत्तिर्ण भएका ब्यजतिह셁को स्वास््य परीऺर् रोजगार आवेदन फाराम ऱगायिका कायहण 셁को बबस्ििृ त्तववरर् यस कायाणऱयको वेवसाइटमा तछटै प्रकामिि गररन े छ । भाषा परीऺा उत्तिर्ण ब्यजतिह셁ऱे रोजगार आवेदन फाराम(Job Application Form) भनकण ा ऱागग प्रहरी प्रतिवेदन िर्था स्वास््य परीऺर्मा समेि सफऱ हुन ु पन े छ। सार्थ ै कु न ै "क" बगकण ो बकℂ मा आफ्न ै नाममा िािा िोऱी सो को प्रमार् एव ं स륍बजधिि ब्यजतिको ब्यजतिगि ईमेऱ ठेगाना अतनवाय ण 셁पमा पेि गन ुण पन े ब्य ह ो र ा स म ेि स 륍 ब ज ध ि ि स ब ैक ो ज ा न क ार ी क ा ऱ ा ग ग य ो स ूच न ा प्र क ा म ि ि ग र ी ए क ो छ । पुनश्च: HRD Service of Korea को प्राप्ि पत्रानुसार यस पटकको Skill Test नहुन े ब्यहोरा समेि स륍बजधिि सबैको जानकारी गराईधछ । Registration No Name Industry No 1 10100003 RAI YOGENDRA Manufacturing > Assemble 2 10100010 KHATIWADA ROSHAN Manufacturing > Assemble 3 10100012 SHARMA PRADIP RAJ Agriculture and Farming of Animals > Livestocks 4 10100015 BADUWAL LALIT BAHADUR Manufacturing > Wood joinery 5 10100025 TAMANG MANISH Manufacturing > Assemble 6 10100032 RAI BHARATRAJ Manufacturing > Wood joinery -

The Thangmi of Nepal and India Sara Shneiderman, Mark Turin

Revisiting ethnography, recognizing a forgotten people: The Thangmi of Nepal and India Sara Shneiderman, Mark Turin To cite this version: Sara Shneiderman, Mark Turin. Revisiting ethnography, recognizing a forgotten people: The Thangmi of Nepal and India. Studies in Nepali History and Society, Mandala Book Point, 2006, 11 (1), pp.97- 181. halshs-03083422 HAL Id: halshs-03083422 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-03083422 Submitted on 27 Jan 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. 96 Celayne Heaton Shrestha Onta, Pratyoush. 1996'1. Ambivalence Denied: The Making of Ra~triya Itihas in REVISITING ETHNOGRAPHY, RECOGNIZING Panchayat Era Textbooks. Contrihutions to Nepalese Studies 23(1): 213 254. AFORGOTTEN PEOPLE: THE THANGMI OF Onta, Pratyoush. 1996b. Creating a Brave Nepali Nation in British India: the NEPAL AND INDIA Rhetoric of Jati Improvement, Rediscovery of Bhanubhakta, and the Writing of Blr History. Studies in Nepali Historv and Society I(I): 37-76. Sara Shneiderman and Mark Turin Onta, Pratyoush. 1997. Activities in a 'Fossil State': Balkrishna Sarna and the Improvisation of Nepali Identity. Studies in Nepali History and Society 2(\): 69-102. There is no idea about the origin of the Thami communitv or the term Perera, Jehan.