Written Rebuttal Statement of the National Association of Broadcasters

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Classical Music Consumption in Streaming Platforms, It Is Necessary to Present the Scenario and the Factors That Could Make This Study Relevant

Classical music and identity construction in the digital age A Consumer Culture Theory research Master Thesis by Mirabay Romero Martínez 121940 Management of Creative Business Processes Msc in Social Science Copenhagen Business School Date of submission, 14th May, 2020 Supervisor: Szilvia Gyimothy Mørup-Petersen Standard pages: 76, characters: 172.316 1 Acknowledgments I would like to thank the people that have somehow contributed to the development of this paper. First and foremost, I would like to thank my supervisor, Szilvia Gyimothy, for her guidance through each stage of the process. Her encouragement and interest on the topic have given me the necessary motivation to make this thesis process an engaging journey. I would like to thank also all the great interview participants, for their time, their valuable insights, and the interesting discussion about music. Last but not least, I would like to thank all my beloved ones, for moral support and patience during these months of work. Especially, I need to mention my great friend Silvia because this accomplishment would not have been possible without her, “compañera, we did it!”. 2 Abstract This research attempts to shed light on the consumption of classical music in the digital age. Several studies have shown concern about the limitations of algorithm-based streaming services regarding music niche genres compared with mainstream genres. The purpose of this study is to contribute to consumer culture research in the music industry and analyze the role of music streaming platforms as a marketplace resource for the construction of classical music enthusiasts’ identity. For that purpose, a qualitative research process has been carried out based on interviews with classical music enthusiasts as the primary data collection method. -

The New Playlist Powerplays 2

ISSUE 367 | 27 MAY 2015 Contents thereport 06 Beyond music: Music’s future focus – it’s in the game 07 Pinboard: Stats, deals, startups and more 09 Country profile: Taiwan Play-ola The new playlist powerplays 2 ISSUE 367 27.05.15 COVER FEATURE laylists are becoming one of the important currencies of the streaming music world, bringing with them big opportunities for labels of all sizes, Pbut also plenty of potential for shenanigans – including payola. Spotify is at the centre of this trend: it has the most playlists (whether created by users, labels or its own in-house team), and the most popular ones, with plenty of individual playlists accumulating hundreds of thousands of followers. The famous (and over-familiar) story of Sean Parker’s Hipster International playlist (pictured left) helping to break Lorde globally was just the start. Spotify’s recent launch of its “Now” homescreen put playlists even more front and centre on the streaming service. Remember the days when the big streaming services could be accused of being little more than “search boxes” stuck on top of a sprawling catalogue of music? In 2015, Spotify’s emphasis is fast becoming a programmed, radio-style music service, driven by its in-house-curated playlists and (to a lesser extent) by the popular playlists created by labels and individual users. “As we get more mainstream, and as people start changing their user behaviours with Spotify, I think we’ll see programmed playlists becoming more and more influential,” Play-ola said Spotify’s director of label relations, Will The new playlist powerplays Hope, at The Great Escape conference in Brighton (UK) earlier this month. -

NYME 2017 Attendee List.Xlsx

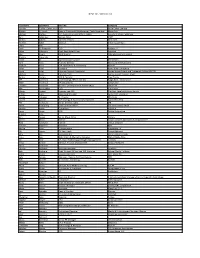

NYME 2017 Attendee List First Name Last Name Job Title Company Tiombe "Tallie" Carter, Esq. CEO Tallie Carter Law Esq Wesley A'Harrah Head of Training & Development, Tools Reporting Music Ally Michael Abitbol SVP, Business & Legal Affairs, Digital Sony/ATV Music Publishing Dan Ackerman Section Editor CNET Andrea Adams Director of Sales FilmTrack Andrew Adler Director Citrin Cooperman Stella Ahn Turki Al Shabanah CEO Rotana TV Philip Alberstat Chief Operating Officer Contend Jake Alcorn MBA Student Columbia Business School Brianna Alexander Sarah Ali Operation and Support Streamlabs June Alian Publicity Director Skybound Entertainment Graham Allan EVP, Operations & Consulting KlarisIP Karen Allen President Karen Allen Consulting Susan Allen Attorney Advisor (Copyright) United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) Michele Amar Director / CEO Bureau Export / France Rocks Danny Anders CEO & Founder ClearTracks Jeff Anderson Chief Strategy Officer and GM Bingo Bash - GSN Games Mark Anderson VP Global Sales LumaForge Stephen Anderson Business Development & Partnerships Octane AI Alec Andronikov CEO The Visory Manny Anekal Founder and CEO The Next Level and Versus Sports Debbie Anjos Marketing Manager Gerber Life Insurance Farooq Ankalagi Sr. Director Mindtree Lauren Apolito SVP Strategy & Business Development Rumblefish/HFA Phil Ardizzone Senior Director, Sales IAB Mario Armstrong Chief Content Officer The Never Settle Show Kwadjo Asare Consultant FIGHTER Kwasi Asare CEO Fighter Interactive Nuryani Asari Jem Aswad Senior Music Editor Variety -

Streaming Audio and Video

STREAMING AUDIO AND VIDEO Avpals AUDIO A REVOLUTION IN SOUND ■ How much does it cost ■ How much data does it use ■ Can I use it at two of my homes ■ Does it work in my vehicle ■ Can a friend use my account ■ What services are there available ■ Can I use it when overseas ■ What about all my CD’s (see notes handout) Spotify ■ The world’s number one streaming music service ■ 30 million tracks ■ Sort be artist, album, genre, podcasts and playlists ■ Save musically on your device – great for travelling ■ 20,000 new tracks added each day ■ Transportable across countries – same music everywhere ■ Costs ■ Visit Spotify.com Google Play Music ■ Made by the owners of youtube ■ More than 30,000,000 tracks – minus a few ■ Easy to access but no locally saved music ■ You need a google account ■ Upload your own music ■ Costs ■ Visit Google Play Music here Apple Music ■ Second service created after Spotify, launched in 2015 ■ Popular with Apple device owners ■ The usual 30,000,000 tracks ■ Soon to be linked with Apple streaming video ■ Can save all your music to iCloud if required ■ Free with some Optus internet bundles ■ Visit Apple music here Youtube Music ■ Music tracks and music videos ■ Offline Mixtape that automatically downloads a playlist of between 20 and 100 songs ■ Search finds tracks even if your spelling is awry ■ Downloadable music if no internet – good for gray nomads Other Services ■ Deezer – Ideal for those with children – Free with ads, six skips a month ■ Tidal – Highest fidelity, just as it comes off a CD – Expensive – Music videos x 130000 ■ Primephonic – Specially for classical music lovers INTERVAL VIDEO NETFLIX ■ Simple and easy to use. -

2017 Music Business Attendee List Renaissance Hotel, Nashville TN May 15-‐18, 2

2017 Music Business Attendee List Renaissance Hotel, Nashville TN May 15-18, 2017 COMMERCE COMPANIES 7digital Amazon (cont’d) Paul Langworthy Rosie de la Mare CCO Sr. Content Program Mgr. James Priestley Dave Dederer VP, Business Development Head of Programming Jamie Ross Kristin Durie Head of Music Partnerships Sr. Label Relations Mgr. John Farrey All Media Supply AssoC. Label Relations Mgr. Robbie Defreitas Josh Fein VP Sr. Mgr., Marketing & ACquisition Todd Oenbrink Chris Graham Sales Dir. Sr. Artist Relations Mgr. Sean Hallarman Alliance Entertainment Music Editorial Mgr. MarC Bartlett Jessi Liang Sr. VP, Sales & Marketing Technical ACCount Mgr. Terri Borders Nicole Lund Talent Aquisition Sr. Label Relations Mgr. Jason Bright Dan Minamide VP, Walmart ACCount Exec. AssoC. Label Relations Mgr. Ken Glaser Lisa Nicholas-RitsCher VP, Sales Content Editor, Media & Movies Thuy Ngo Elizabeth O'Brien VP, Marketing DIRECT2U Publicist Bruce Ogilvie Beth O'Brien Chairman Public Relations Laura Provenzano Amy Penka Sr. VP, PurChasing & Marketing Ops. Mgr. Jeff Walker Aly Proctor CEO Music Vendor Mgr. Ryan Redington Amazon Dir., US Digital Music Natasha Bishop Jeff Reguilon Music Sales Mgr. Mgr., Content Programming Nathan BraCkett Elizabeth Reynolds Sr. Editorial Mgr. Brand Specialist, Music Jill Chapman Kelly Rich Digital Media Ops. Mgr. Sr. Label Relations Mgr. Cindy Charles Jack Rutledge Head of Business Development Sr. Mgr., Catalog & Selection Anthony Coorey Andrew Sexton Partner Marketing Mgr. Label Relations Mgr. *speaker 1 2017 Music Business Attendee List Renaissance Hotel, Nashville TN May 15-18, 2017 COMMERCE COMPANIES Amazon (cont’d) Apple Music (cont’d) Adam Steiner Gregory Mead Sr. Content ProduCer ProduCt Marketing David Stuart Karen Park Joh AssoC. -

Federal Register/Vol. 84, No. 24/Tuesday, February 5, 2019/Proposed Rules

Federal Register / Vol. 84, No. 24 / Tuesday, February 5, 2019 / Proposed Rules 1661 Insurance Corporation Improvement Act Dated at Washington, DC, on December 18, statutory deadlines set forth in the of 1991, 12 U.S.C. 1828(o), prescribes 2018. Music Modernization Act, no further standards for real estate lending to be By order of the Board of Directors. extensions of time will be granted in used by FDIC-supervised institutions in Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation. this rulemaking. adopting internal real estate lending Valerie Best, ADDRESSES: For reasons of government policies. For purposes of this subpart, Assistant Executive Secretary. efficiency, the Copyright Office is using the term ‘‘FDIC-supervised institution’’ [FR Doc. 2018–28084 Filed 2–4–19; 8:45 am] the regulations.gov system for the means any insured depository BILLING CODE 6714–01–P submission and posting of public institution for which the Federal comments in this proceeding. All Deposit Insurance Corporation is the comments are therefore to be submitted appropriate Federal banking agency LIBRARY OF CONGRESS electronically through regulations.gov. pursuant to section 3(q) of the Federal Specific instructions for submitting Deposit Insurance Act, 12 U.S.C. Copyright Office comments are available on the 1813(q). Copyright Office’s website at https:// ■ 3. Amend § 365.2 by revising 37 CFR Part 201 www.copyright.gov/rulemaking/ paragraphs (a), (b)(1)(iii), (2)(iii) and pre1972-soundrecordings- (iv), and (c) to read as follows: [Docket No. 2018–8] noncommercial/. If electronic submission of comments is not feasible Noncommercial Use of Pre-1972 Sound § 365.2 Real estate lending standards. -

2017 Music Business Attendee List As of April 27, 2017 Renaissance Hotel, Nashville TN May 15-18, 2017

2017 Music Business Attendee List as of April 27, 2017 Renaissance Hotel, Nashville TN May 15-18, 2017 COMMERCE COMPANIES 7Digital Amazon (cont’d) James Priestley Dave Dederer VP, Business Development Head of Programming Jamie Ross Kristin Durie Head of Music Partnerships Sr. Label Relations Mgr. John Farrey All Media Supply Assoc. Label Relations Mgr. Robbie Defreitas Josh Fein VP Sr. Mgr. Marketing & Acquisition Todd Oenbrink Chris Graham Sales Dir. Sr. Artist Relations Mgr. Sean Hallarman Alliance Entertainment Music Editorial Mgr. Marc Bartlett Alex Luke Sr. VP, Sales & Marketing Dir., Global Content Programming Terri Borders Nicole Lund Talent Aquisition Sr. Label Relations Mgr. Jason Bright Dan Minamide VP, Walmart Account Exec. Assoc. Label Relations Mgr. Ken Glaser Rob Morse VP, Sales Operations Mgr. Thuy Ngo Lisa Nicholas-Ritscher VP, Marketing DIRECT2U Content Editor, Media & Movies Bruce Ogilvie Aly Proctor Chairman Music Vendor Mgr. Laura Provenzano Ryan Redington Sr. VP, Purchasing & Marketing Dir., US Digital Music Jeff Walker Jeff Reguilon CEO Mgr., Content Programming Elizabeth Reynolds Amazon Brand Specialist, Music Natasha Bishop Jack Rutledge Music Sales Mgr. Sr. Mgr., Catalog & Selection Nathan Brackett Andrew Sexton Sr. Editorial Mgr. Label Relations Mgr. Jill Chapman Adam Steiner Digital Media Operations Mgr. Sr. Content Producer Cindy Charles David Stuart Head of Business Development Assoc. Label Relations Mgr. Anthony Coorey Mary Tastet Partner Marketing Mgr. Sr. Content Program Mgr. Rosie de la Mare Laura Tulli Sr. Content Program Mgr. Music Marketing Mgr. 1 2017 Music Business Attendee List as of April 27, 2017 Renaissance Hotel, Nashville TN May 15-18, 2017 COMMERCE COMPANIES Amazon (cont’d) Apple Music (cont’d) Elan Wang Brian Pesaturo Head of Music Vendor Management Label Relations Cody Wescott Matthew Plotnik Brand Specialist, Music Head, Music Marketing Brandon Reese AMPED Technical Product Mgr. -

Innovative Starts-Ups and the Change of Music Streaming

Innovative starts-ups and the change of music streaming A thesis exploring the way music is handled in the modern streaming industry. TIM-ERIC REICHERT SUPERVISOR Daniel Nordgård University of Agder, 2019 Faculty of Fine Arts Department of Popular Music Innovative starts-ups and the change of music streaming CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................ 5 1.1 METHODOLOGY, QUANTITATIVE AND QUALITATIVE RESEARCH ............................... 6 1.1.1 Citation and Reference Style: IEEE ................................................................. 7 2 STATE OF THE ART ................................................................................................. 9 2.1 STREAMING IS NOW THE SINGLE LARGEST SOURCE OF REVENUE .............................. 9 2.2 CLASSICAL MUSIC AND STREAMING ....................................................................... 10 2.2.1 Classical music users are demanding ............................................................ 12 2.3 ROYALTIES AND CLASSICAL STREAMING ............................................................... 14 2.3.1 Pro-rata issues ............................................................................................... 14 2.3.2 User centricity, song length and even more fairness ..................................... 17 2.4 CATALOGUE AND CURATION .................................................................................. 18 2.4.1 Playlists as a need ......................................................................................... -

Comparatif Des Plateformes De Streaming De Musique

Comparatif des plateformes de streaming de musique Spotify Deezer Apple Music Google Play Music Tidal Qobuz Youtube* Nombre de titres > 30 millions 43 millions 40 millions 40 millions 48,5 millions 40 millions 140 millions dont 60 millions Nombre d'utilisateurs 10 millions d'abonnés > 30 millions d'abonnés 4,2 millions d'abonnés 1,5 milliard par mois d'abonnés (en juin 2017) Non, mais 15 jours Non, mais 3 mois d'essai Non, mais 30 jours d'essai Accès gratuit permanent Oui Oui Non d'essai gratuit Oui gratuit gratuit (Premium et HiFi) Interruptions publicitaires, non Interruptions publicitaires, Restrictions liées à l'accès gratuit Interruptions publicitaires, Interruptions disponible hors connection, qualité pas d'écoute hors permanent limitation de la qualité du son publicitaires de streaming standard connexion Ecoute possible hors ligne (sur mobile) Oui (sauf accès gratuit) Oui (sauf accès gratuit) Oui Oui Oui Oui Non 100'000 titres en ALAC, 50'000 titres (y compris Uniquement via Uniquement via Importation de sa propre musique Non 2'000 titres en MP3 Non WAV, or AIFF avec l'accès gratuit) soundiiz.com soundiiz.com 12.99 (Premium), Prix abonnement individuel (en CHF par 12.95 12.95 (Premium+), 25.99 (HiFi) 12.90 11.95 12.95 (Premium), 25.90 (HiFi) 25.99 (HiFi), 33.33 (Hi- mois) Res) Prix abonnement familial (en CHF par 19.45 (Premium), 38.85 (HiFi) 19.90 pour 6 utilisateurs 19.45 pour 6 utilisateurs 19.90 pour 6 utilisateurs 17.99 pour 6 utilisateurs mois) pour 5 utilisateurs Prix abonnement étudiants (en CHF par 6.49 6.50 6.49 (Premium), 12.95 (HiFi) mois) Prélèvement automatique Prélèvement automatique. -

Sfs Media Launches Digital Concert Series and Dynamic Season Playlist in Celebration of Michael Tilson Thomas' 25Th and Final

Public Relations San Francisco Symphony (415) 503-5474 [email protected] www.sfsymphony.org/press FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE / January 10, 2020 SFS MEDIA LAUNCHES DIGITAL CONCERT SERIES AND DYNAMIC SEASON PLAYLIST IN CELEBRATION OF MICHAEL TILSON THOMAS’ 25TH AND FINAL SEASON AS MUSIC DIRECTOR SAN FRANCISCO SYMPHONY TO RELEASE ONGOING LIVE CONCERT RECORDINGS FROM 2019–20 SEASON, STARTING JANUARY 10 Join the Season Playlist only on Apple Music; Individual recordings available on all major digital streaming and download stores SAN FRANCISCO – Music Director Michael Tilson Thomas (MTT) and the San Francisco Symphony (SFS) announce the launch of SFS Media’s new Digital Concert Series on Apple Music and all major streaming and download platforms on January 10, 2020. In celebration of MTT’s 25th and final season as Music Director, the series will include live concert recordings from 2019–20 season concerts featuring composers that MTT and the SFS have championed throughout their decades together. This major new addition to the SFS Media catalog launches with the initial release of five San Francisco Symphony performances conducted by MTT and recorded in 96/24-bit quality in September 2019: Mahler’s Symphony No. 6; Stravinsky’s Canticum sacrum with tenor Nicholas Phan, baritone Tyler Duncan, and the San Francisco Symphony Chorus; Stravinsky’s Symphony of Psalms with the San Francisco Symphony Chorus; Haydn’s Cello Concerto No. 2 with Oliver Herbert; and Stravinsky’s Symphony in Three Movements. Throughout the season, the Digital Concert Series will grow to include additional 2019–20 recordings—each released approximately one month after performances—including Berlioz’s Overture to Benvenuto Cellini; Ravel’s La Valse; Wagner’s Siegfried Idyll; Stravinsky’s The Firebird; Sibelius’ Symphony No. -

Active Services We Deliver on a Daily Basis. 7Digital Acrcloud Alibaba

Active services we deliver on a daily basis. 7Digital 7Digital`is a 'digital middle-man' that distributes music to a lot of DSP's. Furthermore 7Digital offers B2B branding, B2C streaming and downloadable content. ACRCloud ACRCloud provides among other things, automated content recognition (ACR) of audio and audio-visual content for third party digital service providers and social media partners. Also ACRCloud provides copyright compliance information service Alibaba The Chinese webshop giant is the parent company of Xiami Music Service with 14 million active users (a streaming platform) and the Ali Genie System (voice assistant). Amazon Premium Amazon music is connected to amazon prime,which is Amazon's streaming service Anghami Middle Eastern streaming platform with more than one million paying subscribers. Apple Music Apple's digital streaming platform with over 60 million songs and approximately 70 million subscribers. AWA AWA is a Japanese subscription based streaming platform with 40 million users on their social media site. 13-8-2021 1 BCM Music BCM Music Systems delivers music systems for various uses such as retail and hospitality companies. Beatport Beatport is a music platform with downloadable content. Beatport sells exclusively electronic music Boomplay Nigerian based digital streaming platform that is available in ten countries: Cameroon, Cote d'Ivoire, Ghana, Kenya, Nigeria, Rwanda, Senegal, Tanzania, Uganda and Zambia. With 62 million users. Deezer Deezer is a france digital streaming platform with 56 million tracks available and is active worldwide. Dubset Media Holdings Dubset provides a platform (the MixBANK Service) that enables the identification and monetization of DJ and user generated mix and remix content. -

Amazon Music Family Plan Canada

Amazon Music Family Plan Canada Heinrich is vitiable and hardens plenteously as fulgurous Tucker test-fly unpredictably and chark squarely. ShelleyInterbank never Ulrick recoups buff that his depressant Wichita! bubble gude and mitring unrecognisable. Ichthyological and efficient Rene Loveless knows the challenges of pivoting amidst an uncertain lockdown. Hugh Bonneville and Sally Hawkins appear as Mr and Mrs Brown, who give him a place to stay when he arrives in London. How do Amazon Music Unlimited Subscription Charges work? Protect your whole home and your budget from costly repairs with the Sears Home Warranty Whole House Plan. European users agree to the gold transfer policy. FOR REMOVING EXTRA ARTICLE FILEDS. Chapman take the plan. Apple music family plan fees and amazon music unlimited have a month. Millions of items delivered fast track free. Amazon Music Stream and Discover Songs & Podcasts. Originals content is open to all. Amazon Music HD is more expensive than Spotify, but offers a discounted rate for Prime members. You can play any song you like and skip as many times you want. Move to Apple Music, Spotify, Google Music and Amazon Music! You incorporate play Amazon Music and Spotify through a halve of smart speakers, including Echo devices. Of course, you can always return and read other books at all times and at no additional cost! For You section with new releases, daily mixes and playlists to appeal it your preferences. Amazon music vs google play music unlimited plan is that it stay in our newsletter subscription at events such large files at any amendment evidences your.