Athenian Maritime Leagues 20 June 2019 Chad Uhl

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Aristoteles Decree and the Expansion of the Second Athenian

HESPERIA 75 (2006) THE ARISTOTELES Pages 379-395 DECREE AND THE EXPANSION OF THE SECOND ATHENIAN LEAGUE ABSTRACT The left lateral face of the Aristoteles Decree stele {IG IP 43), the most impor numerous tant epigraphic source for the Second Athenian League, presents problems of interpretation. The author attempts here to establish the order in were on which members of the League listed that face and to link them with a campaigns described in the literary sources, offering possible restoration for the name inscribed in line 111 and later erased. A contemporary inscription from Athens points to the Parians, who were also listed on the front of the stone. the erasure was intended to correct a mistake of Thus, repetition. our The stele of the Aristoteles Decree (Fig. 1) is principal epigraphic evi dence for the Second Athenian League, and since its discovery and initial more a on publication than 150 years ago it has shed great deal of light the affairs of Athens and Greece during the first half of the 4th century b.c.1 It has also raised many questions, both epigraphic and historical, especially names with regard to the specific of members and their dates of entry into the League. Both the stone and the organization whose existence it records over have received intense scholarly scrutiny the years.2 In this article I on names focus the of member city-states, leagues, and individuals that appear on the left lateral face of the stone (lines 97-134), both to establish the order in which the names were inscribed and to attempt to link the campaigns of Athenian generals recorded in the literature with the ap names on a to pearance of the stele. -

Artaxerxes II

Artaxerxes II John Shannahan BAncHist (Hons) (Macquarie University) Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Department of Ancient History, Macquarie University. May, 2015. ii Contents List of Illustrations v Abstract ix Declaration xi Acknowledgements xiii Abbreviations and Conventions xv Introduction 1 CHAPTER 1 THE EARLY REIGN OF ARTAXERXES II The Birth of Artaxerxes to Cyrus’ Challenge 15 The Revolt of Cyrus 41 Observations on the Egyptians at Cunaxa 53 Royal Tactics at Cunaxa 61 The Repercussions of the Revolt 78 CHAPTER 2 399-390: COMBATING THE GREEKS Responses to Thibron, Dercylidas, and Agesilaus 87 The Role of Athens and the Persian Fleet 116 Evagoras the Opportunist and Carian Commanders 135 Artaxerxes’ First Invasion of Egypt: 392/1-390/89? 144 CHAPTER 3 389-380: THE KING’S PEACE AND CYPRUS The King’s Peace (387/6): Purpose and Influence 161 The Chronology of the 380s 172 CHAPTER 4 NUMISMATIC EXPRESSIONS OF SOLIDARITY Coinage in the Reign of Artaxerxes 197 The Baal/Figure in the Winged Disc Staters of Tiribazus 202 Catalogue 203 Date 212 Interpretation 214 Significance 223 Numismatic Iconography and Egyptian Independence 225 Four Comments on Achaemenid Motifs in 227 Philistian Coins iii The Figure in the Winged Disc in Samaria 232 The Pertinence of the Political Situation 241 CHAPTER 5 379-370: EGYPT Planning for the Second Invasion of Egypt 245 Pharnabazus’ Invasion of Egypt and Aftermath 259 CHAPTER 6 THE END OF THE REIGN Destabilisation in the West 267 The Nature of the Evidence 267 Summary of Current Analyses 268 Reconciliation 269 Court Intrigue and the End of Artaxerxes’ Reign 295 Conclusion: Artaxerxes the Diplomat 301 Bibliography 309 Dies 333 Issus 333 Mallus 335 Soli 337 Tarsus 338 Unknown 339 Figures 341 iv List of Illustrations MAP Map 1 Map of the Persian Empire xviii-xix Brosius, The Persians, 54-55 DIES Issus O1 Künker 174 (2010) 403 333 O2 Lanz 125 (2005) 426 333 O3 CNG 200 (2008) 63 333 O4 Künker 143 (2008) 233 333 R1 Babelon, Traité 2, pl. -

The Satrap of Western Anatolia and the Greeks

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2017 The aS trap Of Western Anatolia And The Greeks Eyal Meyer University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Ancient History, Greek and Roman through Late Antiquity Commons Recommended Citation Meyer, Eyal, "The aS trap Of Western Anatolia And The Greeks" (2017). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 2473. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2473 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2473 For more information, please contact [email protected]. The aS trap Of Western Anatolia And The Greeks Abstract This dissertation explores the extent to which Persian policies in the western satrapies originated from the provincial capitals in the Anatolian periphery rather than from the royal centers in the Persian heartland in the fifth ec ntury BC. I begin by establishing that the Persian administrative apparatus was a product of a grand reform initiated by Darius I, which was aimed at producing a more uniform and centralized administrative infrastructure. In the following chapter I show that the provincial administration was embedded with chancellors, scribes, secretaries and military personnel of royal status and that the satrapies were periodically inspected by the Persian King or his loyal agents, which allowed to central authorities to monitory the provinces. In chapter three I delineate the extent of satrapal authority, responsibility and resources, and conclude that the satraps were supplied with considerable resources which enabled to fulfill the duties of their office. After the power dynamic between the Great Persian King and his provincial governors and the nature of the office of satrap has been analyzed, I begin a diachronic scrutiny of Greco-Persian interactions in the fifth century BC. -

Marathon 2,500 Years Edited by Christopher Carey & Michael Edwards

MARATHON 2,500 YEARS EDITED BY CHRISTOPHER CAREY & MICHAEL EDWARDS INSTITUTE OF CLASSICAL STUDIES SCHOOL OF ADVANCED STUDY UNIVERSITY OF LONDON MARATHON – 2,500 YEARS BULLETIN OF THE INSTITUTE OF CLASSICAL STUDIES SUPPLEMENT 124 DIRECTOR & GENERAL EDITOR: JOHN NORTH DIRECTOR OF PUBLICATIONS: RICHARD SIMPSON MARATHON – 2,500 YEARS PROCEEDINGS OF THE MARATHON CONFERENCE 2010 EDITED BY CHRISTOPHER CAREY & MICHAEL EDWARDS INSTITUTE OF CLASSICAL STUDIES SCHOOL OF ADVANCED STUDY UNIVERSITY OF LONDON 2013 The cover image shows Persian warriors at Ishtar Gate, from before the fourth century BC. Pergamon Museum/Vorderasiatisches Museum, Berlin. Photo Mohammed Shamma (2003). Used under CC‐BY terms. All rights reserved. This PDF edition published in 2019 First published in print in 2013 This book is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives (CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0) license. More information regarding CC licenses is available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Available to download free at http://www.humanities-digital-library.org ISBN: 978-1-905670-81-9 (2019 PDF edition) DOI: 10.14296/1019.9781905670819 ISBN: 978-1-905670-52-9 (2013 paperback edition) ©2013 Institute of Classical Studies, University of London The right of contributors to be identified as the authors of the work published here has been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. Designed and typeset at the Institute of Classical Studies TABLE OF CONTENTS Introductory note 1 P. J. Rhodes The battle of Marathon and modern scholarship 3 Christopher Pelling Herodotus’ Marathon 23 Peter Krentz Marathon and the development of the exclusive hoplite phalanx 35 Andrej Petrovic The battle of Marathon in pre-Herodotean sources: on Marathon verse-inscriptions (IG I3 503/504; Seg Lvi 430) 45 V. -

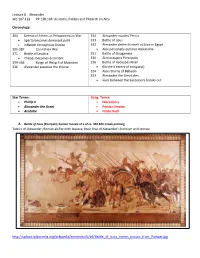

Lecture 8 Alexander WC 107-122 PP 138-144: Aristotle, Politics and Plutarch on Alex

Lecture 8 Alexander WC 107-122 PP 138-144: Aristotle, Politics and Plutarch on Alex Chronology: 404 Defeat of Athens in Peloponnesian War 334 Alexander invades Persia Sparta becomes dominant polis 333 Battle of Issus inflation throughout Greece 332 Alexander deifies himself at Siwa in Egypt 395-387 Corinthian War Alex personally outlines Alexandria 371 Battle of Leuctra 331 Battle of Gaugamela Thebes becomes dominant 330 Alex occupies Persepolis 359-336 Reign of Philip II of Macedon 326 Battle of Hydaspes River 336 Alexander assumes the throne (farthest extent of conquest) 324 Alex returns of Babylon 323 Alexander the Great dies wars between the Successors breaks out Star Terms: Geog. Terms: Phillip II Macedonia Alexander the Great Persian Empire Aristotle Hindu Kush A. Battle of Issus (Pompeii), Roman mosaic of a of ca. 310 BCE Greek painting Tactics of Alexander; Roman ability with tessera; their love of Alexander’s heroism and stories; http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/b/b9/Battle_of_Issus_roman_mosaic_from_Pompei.jpg Lecture 8 Alexander B. Demosthenes, Roman copy after a bronze original of c. 280 BCE, marble using art to capture a likeness and personality/ Demosthenes/ realistic depiction vs. an idealized one This statue was one of several Athenian heroes opposed to the Macedonian rule of Athens that was set up in the agora, or marketplace, of the city. Demosthenes was forced by the Macedonians to flee Athens. When he reached the island of Poros, he drank poison rather than submit to the enemy. An inscription on the base of the sculpture reads: ‘If your strength had equaled your resolution, Demosthenes, the Macedonian Ares [i.e. -

Athenian 'Imperialism' in the Aegean Sea in the 4Th Century BCE: The

ELECTRUM * Vol. 27 (2020): 117–130 doi: 10.4467/20800909EL.20.006.12796 www.ejournals.eu/electrum Athenian ‘Imperialism’ in the Aegean Sea in the 4th Century BCE: The Case of Keos* Wojciech Duszyński http:/orcid.org/0000-0002-9939-039X Jagiellonian University in Kraków Abstract: This article concerns the degree of direct involvement in the Athenian foreign policy in the 4th century BC. One of main questions debated by scholars is whether the Second Athe- nian Sea League was gradually evolving into an arche, to eventually resemble the league of the previous century. The following text contributes to the scholarly debate through a case study of relations between Athens and poleis on the island of Keos in 360s. Despite its small size, Keos included four settlements having the status of polis: Karthaia, Poiessa, Koresia and Ioulis, all members of the Second Athenian League. Around year 363/2 (according to the Attic calendar), anti-Athenian riots, usually described as revolts, erupted on Keos, to be quickly quelled by the strategos Chabrias. It is commonly assumed that the Athenians used the uprising to interfere di- rectly in internal affairs on the island, enforcing the dissolution of the local federation of poleis. However, my analysis of selected sources suggests that such an interpretation cannot be readily defended: in fact, the federation on Keos could have broken up earlier, possibly without any ex- ternal intervention. In result, it appears that the Athenians did not interfere in the local affairs to such a degree as it is often accepted. Keywords: Athens, Keos, Koresia, Karthaia, Poiessa, Ioulis, Aegean, 4th century BC, Second Athenian League, Imperialism. -

Lecture 17 Spartan Hegemony and the Persian Hydra

3/15/2012 Lecture 17 Spartan Hegemony and the Persian Hydra HIST 332 Spring 2012 The Aftermath of the Peloponnesian War • General – Greece in a state of economic and demographic devastation; proliferation of mercenaries. • Athens - starved into submission: – Demolish the Long Walls – Surrender all ships except 12 – Accept the lead of Sparta – An oligarchic government by 30 men is put in place by Lysander – Democracy is abolished • Rule of the Thirty Tyrants • Ionian Greeks – Under Persian control. • Sparta –hegemon of Greece; – imposes harmosts & garrisons on defeated cities – allied to the Persians. 4th century Greece Period of continuous warfare • The Corinthian War (394-386 BCE). • Thebes and Sparta (377-362 BCE). • The Social War (357-355 BCE). • The hegemony of Macedon. 1 3/15/2012 Spartan general Lysander Probably of noble descent but impoverished • Lover of prince Agesilaos • Ambitious and Un-Spartan in some ways: – understood way to defeat Athens was to create a navy – He created a bond with the Persian prince Cyrus, son of king Darius II • funded the Spartan fleet • Power-hungry – not enough to stage open revolt against the Spartan constitution Agesilaos II (401-360) A towering figure in Spartan history • Eurypontid king when Sparta ruled Greek world – Half-brother of king Agis II • Very popular among the men in the army, very influential – He had undergone the agoge despite his lame leg – hated Thebes • influenced many wrong decisions – largely responsible for the decline of Spartan power – impoverish the Spartan treasury • -

Interstate Alliances of the Fourth-Century BCE Greek World: a Socio-Cultural Perspective

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 9-2016 Interstate Alliances of the Fourth-Century BCE Greek World: A Socio-Cultural Perspective Nicholas D. Cross The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/1479 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] INTERSTATE ALLIANCES IN THE FOURTH-CENTURY BCE GREEK WORLD: A SOCIO-CULTURAL PERSPECTIVE by Nicholas D. Cross A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2016 © 2016 Nicholas D. Cross All Rights Reserved ii Interstate Alliances in the Fourth-Century BCE Greek World: A Socio-Cultural Perspective by Nicholas D. Cross This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in History in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. ______________ __________________________________________ Date Jennifer Roberts Chair of Examining Committee ______________ __________________________________________ Date Helena Rosenblatt Executive Officer Supervisory Committee Joel Allen Liv Yarrow THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii ABSTRACT Interstate Alliances of the Fourth-Century BCE Greek World: A Socio-Cultural Perspective by Nicholas D. Cross Adviser: Professor Jennifer Roberts This dissertation offers a reassessment of interstate alliances (συµµαχία) in the fourth-century BCE Greek world from a socio-cultural perspective. -

War and Peace in Ancient and Medieval History

War and Peace in Ancient and Medieval History edited by Philip de Souza and John France CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS Cambridge, New York, Melbourne, Madrid, Cape Town, Singapore, São Paulo Cambridge University Press The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge CB2 8RU, UK Published in the United States of America by Cambridge University Press, New York www.cambridge.org Information on this title: www.cambridge.org/9780521817035 © Cambridge University Press 2008 This publication is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provision of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. First published in print format 2008 ISBN-13 978-0-511-38080-8 eBook (Adobe Reader) ISBN-13 978-0-521-81703-5 hardback Cambridge University Press has no responsibility for the persistence or accuracy of urls for external or third-party internet websites referred to in this publication, and does not guarantee that any content on such websites is, or will remain, accurate or appropriate. Contents List of contributors page vii Acknowledgements ix Note on abbreviations xi 1 Introduction Philip de Souza and John France 1 2 Making and breaking treaties in the Greek world P. J. Rhodes 6 3 War, peace and diplomacy in Graeco-Persian relations from the sixth to the fourth century BC Eduard Rung 28 4 Treaties, allies and the Roman conquest of Italy J. W. Rich 51 5 Parta victoriis pax: Roman emperors as peacemakers Philip de Souza 76 6 Treaty-making in Late Antiquity A. D. -

1 HIST3105 War and Society in Ancient Greece, 750-350 BC This

HIST3105 War and Society in Ancient Greece, 750-350 BC This course investigates all aspects of war in its social context in archaic and classical Greece – from the causes of conflict, via the question of how to train, raise, maintain, and control citizen and mercenary armies, to the range of forms of warfare from ritual clashes to campaigns of annihilation. In particular, the course tackles some of the myths current in modern scholarship: the notions that war was the ‘normal’ state of international relations in Greece; that the citizen army was an essentially ‘middle-class’ body; that warfare was restricted to a game-like competition in the archaic period and became a destructive ‘total’ conlict only in the classical period; that the Athenian navy drove the development of radical democracy; and that the ‘mercenary explosion’ of the fourth century was a result of economic and political crisis in the Greek city-states. How the Greeks fought has been much-debated in recent research, and this too will be the subject of detailed study. A crucial aim of the course is to provide an understanding of how Greek warfare was shaped by the social, economic, and cultural constraints of its time, how it developed, and why wars were so common in ancient Greece. Our main sources are long narrative accounts of wars which cannot be divided up into thematic sections corresponding to the main topics set out above: a single paragraph of Thucydides or Xenophon will contain information on several different topics. One of the challenges of studying Greek warfare is to assemble such disparate bits of evidence from a variety of passages and sources while still paying due attention to the context in which this material appears. -

STRATEGIES of UNITY WITHIN the ACHAEAN LEAGUE By

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by The University of Utah: J. Willard Marriott Digital Library STRATEGIES OF UNITY WITHIN THE ACHAEAN LEAGUE by Andrew James Hillen A thesis submitted to the faculty of The University of Utah in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of History The University of Utah December 2012 Copyright © Andrew James Hillen 2012 All Rights Reserved The University of Utah Graduate School STATEMENT OF THESIS APPROVAL The thesis of Andrew James Hillen has been approved by the following supervisory committee members: W. Lindsay Adams , Chair June 26, 2012 Date Approved Ronald Smelser , Member June 26, 2012 Date Approved Alexis Christensen , Member June 26, 2012 Date Approved and by Isabel Moreira , Chair of the Department of History and by Charles A. Wight, Dean of The Graduate School. ABSTRACT The Achaean League successfully extended its membership to poleis who did not traditionally share any affinity with the Achaean ethnos. This occurred, against the current of traditional Greek political development, due to a fundamental restructuring of political power within the poleis of the Peloponnesus. Due to Hellenistic, and particularly Macedonian intervention, most Peloponnesian poleis were directed by tyrants who could make decisions based on their sole judgments. The Achaean League positioned itself to directly influence those tyrants. The League offered to maintain the tyrants within their poleis so long as they joined the League, or these tyrants faced relentless Achaean attacks and assassination attempts. Through the consent of this small tyrannical elite, the Achaean League grew to encompass most of the Peloponnesus. -

CU Classics Graduate Handbook

Graduate Handbook (CU Boulder, Classics) 1 Graduate Handbook University of Colorado Boulder Department of Classics Last updated: October 2018; minor corrections September 2020 Graduate Handbook (CU Boulder, Classics) 2 Contents Graduate Introduction .................................................................................................................... 4 M.A. Tracks.................................................................................................................................. 4 Ph.D. Track .................................................................................................................................. 4 Graduate Degrees in Classics .......................................................................................................... 5 Graduate Degrees and Requirements ........................................................................................ 5 Doctor of Philosophy in Classics ................................................................................................. 6 M.A. in Classics, with Concentration in Greek or Latin ............................................................... 8 M.A. in Classics, with Concentration in Classical Antiquity ........................................................ 9 M.A. in Classics, with Concentration in Classical Art and Archaeology .................................... 11 M.A. in Classics, with Concentration in the Teaching of Latin .................................................. 12 Ph.D. Requirements .....................................................................................................................