Journeying to the Afterlife in Ancient Greece

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Artaxerxes II

Artaxerxes II John Shannahan BAncHist (Hons) (Macquarie University) Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Department of Ancient History, Macquarie University. May, 2015. ii Contents List of Illustrations v Abstract ix Declaration xi Acknowledgements xiii Abbreviations and Conventions xv Introduction 1 CHAPTER 1 THE EARLY REIGN OF ARTAXERXES II The Birth of Artaxerxes to Cyrus’ Challenge 15 The Revolt of Cyrus 41 Observations on the Egyptians at Cunaxa 53 Royal Tactics at Cunaxa 61 The Repercussions of the Revolt 78 CHAPTER 2 399-390: COMBATING THE GREEKS Responses to Thibron, Dercylidas, and Agesilaus 87 The Role of Athens and the Persian Fleet 116 Evagoras the Opportunist and Carian Commanders 135 Artaxerxes’ First Invasion of Egypt: 392/1-390/89? 144 CHAPTER 3 389-380: THE KING’S PEACE AND CYPRUS The King’s Peace (387/6): Purpose and Influence 161 The Chronology of the 380s 172 CHAPTER 4 NUMISMATIC EXPRESSIONS OF SOLIDARITY Coinage in the Reign of Artaxerxes 197 The Baal/Figure in the Winged Disc Staters of Tiribazus 202 Catalogue 203 Date 212 Interpretation 214 Significance 223 Numismatic Iconography and Egyptian Independence 225 Four Comments on Achaemenid Motifs in 227 Philistian Coins iii The Figure in the Winged Disc in Samaria 232 The Pertinence of the Political Situation 241 CHAPTER 5 379-370: EGYPT Planning for the Second Invasion of Egypt 245 Pharnabazus’ Invasion of Egypt and Aftermath 259 CHAPTER 6 THE END OF THE REIGN Destabilisation in the West 267 The Nature of the Evidence 267 Summary of Current Analyses 268 Reconciliation 269 Court Intrigue and the End of Artaxerxes’ Reign 295 Conclusion: Artaxerxes the Diplomat 301 Bibliography 309 Dies 333 Issus 333 Mallus 335 Soli 337 Tarsus 338 Unknown 339 Figures 341 iv List of Illustrations MAP Map 1 Map of the Persian Empire xviii-xix Brosius, The Persians, 54-55 DIES Issus O1 Künker 174 (2010) 403 333 O2 Lanz 125 (2005) 426 333 O3 CNG 200 (2008) 63 333 O4 Künker 143 (2008) 233 333 R1 Babelon, Traité 2, pl. -

The Satrap of Western Anatolia and the Greeks

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2017 The aS trap Of Western Anatolia And The Greeks Eyal Meyer University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Ancient History, Greek and Roman through Late Antiquity Commons Recommended Citation Meyer, Eyal, "The aS trap Of Western Anatolia And The Greeks" (2017). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 2473. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2473 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2473 For more information, please contact [email protected]. The aS trap Of Western Anatolia And The Greeks Abstract This dissertation explores the extent to which Persian policies in the western satrapies originated from the provincial capitals in the Anatolian periphery rather than from the royal centers in the Persian heartland in the fifth ec ntury BC. I begin by establishing that the Persian administrative apparatus was a product of a grand reform initiated by Darius I, which was aimed at producing a more uniform and centralized administrative infrastructure. In the following chapter I show that the provincial administration was embedded with chancellors, scribes, secretaries and military personnel of royal status and that the satrapies were periodically inspected by the Persian King or his loyal agents, which allowed to central authorities to monitory the provinces. In chapter three I delineate the extent of satrapal authority, responsibility and resources, and conclude that the satraps were supplied with considerable resources which enabled to fulfill the duties of their office. After the power dynamic between the Great Persian King and his provincial governors and the nature of the office of satrap has been analyzed, I begin a diachronic scrutiny of Greco-Persian interactions in the fifth century BC. -

Marathon 2,500 Years Edited by Christopher Carey & Michael Edwards

MARATHON 2,500 YEARS EDITED BY CHRISTOPHER CAREY & MICHAEL EDWARDS INSTITUTE OF CLASSICAL STUDIES SCHOOL OF ADVANCED STUDY UNIVERSITY OF LONDON MARATHON – 2,500 YEARS BULLETIN OF THE INSTITUTE OF CLASSICAL STUDIES SUPPLEMENT 124 DIRECTOR & GENERAL EDITOR: JOHN NORTH DIRECTOR OF PUBLICATIONS: RICHARD SIMPSON MARATHON – 2,500 YEARS PROCEEDINGS OF THE MARATHON CONFERENCE 2010 EDITED BY CHRISTOPHER CAREY & MICHAEL EDWARDS INSTITUTE OF CLASSICAL STUDIES SCHOOL OF ADVANCED STUDY UNIVERSITY OF LONDON 2013 The cover image shows Persian warriors at Ishtar Gate, from before the fourth century BC. Pergamon Museum/Vorderasiatisches Museum, Berlin. Photo Mohammed Shamma (2003). Used under CC‐BY terms. All rights reserved. This PDF edition published in 2019 First published in print in 2013 This book is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives (CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0) license. More information regarding CC licenses is available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Available to download free at http://www.humanities-digital-library.org ISBN: 978-1-905670-81-9 (2019 PDF edition) DOI: 10.14296/1019.9781905670819 ISBN: 978-1-905670-52-9 (2013 paperback edition) ©2013 Institute of Classical Studies, University of London The right of contributors to be identified as the authors of the work published here has been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. Designed and typeset at the Institute of Classical Studies TABLE OF CONTENTS Introductory note 1 P. J. Rhodes The battle of Marathon and modern scholarship 3 Christopher Pelling Herodotus’ Marathon 23 Peter Krentz Marathon and the development of the exclusive hoplite phalanx 35 Andrej Petrovic The battle of Marathon in pre-Herodotean sources: on Marathon verse-inscriptions (IG I3 503/504; Seg Lvi 430) 45 V. -

Registration Certificate

1 The following information has been supplied by the Greek Aliens Bureau: It is obligatory for all EU nationals to apply for a “Registration Certificate” (Veveosi Engrafis - Βεβαίωση Εγγραφής) after they have spent 3 months in Greece (Directive 2004/38/EC).This requirement also applies to UK nationals during the transition period. This certificate is open- dated. You only need to renew it if your circumstances change e.g. if you had registered as unemployed and you have now found employment. Below we outline some of the required documents for the most common cases. Please refer to the local Police Authorities for information on the regulations for freelancers, domestic employment and students. You should submit your application and required documents at your local Aliens Police (Tmima Allodapon – Τμήμα Αλλοδαπών, for addresses, contact telephone and opening hours see end); if you live outside Athens go to the local police station closest to your residence. In all cases, original documents and photocopies are required. You should approach the Greek Authorities for detailed information on the documents required or further clarification. Please note that some authorities work by appointment and will request that you book an appointment in advance. Required documents in the case of a working person: 1. Valid passport. 2. Two (2) photos. 3. Applicant’s proof of address [a document containing both the applicant’s name and address e.g. photocopy of the house lease, public utility bill (DEH, OTE, EYDAP) or statement from Tax Office (Tax Return)]. If unavailable please see the requirements for hospitality. 4. Photocopy of employment contract. -

(Eponymous) Heroes

is is a version of an electronic document, part of the series, Dēmos: Clas- sical Athenian Democracy, a publicationpublication ofof e Stoa: a consortium for electronic publication in the humanities [www.stoa.org]. e electronic version of this article off ers contextual information intended to make the study of Athenian democracy more accessible to a wide audience. Please visit the site at http:// www.stoa.org/projects/demos/home. Athenian Political Art from the fi h and fourth centuries: Images of Tribal (Eponymous) Heroes S e Cleisthenic reforms of /, which fi rmly established democracy at Ath- ens, imposed a new division of Attica into ten tribes, each of which consti- tuted a new political and military unit, but included citizens from each of the three geographical regions of Attica – the city, the coast, and the inland. En- rollment in a tribe (according to heredity) was a manda- tory prerequisite for citizenship. As usual in ancient Athenian aff airs, politics and reli- gion came hand in hand and, a er due consultation with Apollo’s oracle at Delphi, each new tribe was assigned to a particular hero a er whom the tribe was named; the ten Amy C. Smith, “Athenian Political Art from the Fi h and Fourth Centuries : Images of Tribal (Eponymous) Heroes,” in C. Blackwell, ed., Dēmos: Classical Athenian Democracy (A.(A. MahoneyMahoney andand R.R. Scaife,Scaife, edd.,edd., e Stoa: a consortium for electronic publication in the humanities [www.stoa.org], . © , A.C. Smith. tribal heroes are thus known as the eponymous (or name giving) heroes. T : Aristotle indicates that each hero already received worship by the time of the Cleisthenic reforms, although little evi- dence as to the nature of the worship of each hero is now known (Aristot. -

Urban Renaissance on Athens Southern Coast: the Case of Palaio Faliro

Issue 4, Volume 3, 2009 178 Urban renaissance on Athens southern coast: the case of Palaio Faliro Stefanos Gerasimou, Anastássios Perdicoúlis Abstract— The city of Palaio Faliro is a suburb of Athens, around 9 II. HISTORIC BACKGROUND km from the city centre of the Greek capital, located on the southern The city of Palaio Faliro is located on the southern coast of coast of the Athens Riviera with a population of nearly 65.000 inhabitants. The municipality of Palaio Faliro has recently achieved a the Region of Attica, on the eastern part of the Faliro Delta, regeneration of its urban profile and dynamics, which extends on an around 9 km from Athens city centre, 13 km from the port of area of Athens southern costal zone combining historic baths, a Piraeus and 40 km from Athens International Airport. It marina, an urban park, an Olympic Sports Complex and the tramway. extends on an area of nearly 457ha [1]. According to ancient The final result promotes sustainable development and sustainable Greek literature, cited in the official website of the city [2], mobility on the Athens coastline taking into consideration the recent Palaio Faliro was founded by Faliro, a local hero, and used to metropolisation of the Athens agglomeration. After a brief history of the municipality, we present the core of the new development. be the port of Athens before the creation of that of Piraeus. Behind the visible results, we highlight the main interactions among Until 1920, Palaio Faliro was a small seaside village with the principal actors that made this change possible, and constitute the few buildings, mainly fields where were cultivated wheat, main challenges for the future. -

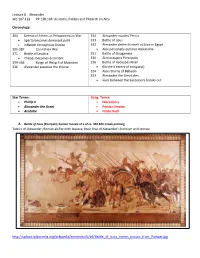

Lecture 8 Alexander WC 107-122 PP 138-144: Aristotle, Politics and Plutarch on Alex

Lecture 8 Alexander WC 107-122 PP 138-144: Aristotle, Politics and Plutarch on Alex Chronology: 404 Defeat of Athens in Peloponnesian War 334 Alexander invades Persia Sparta becomes dominant polis 333 Battle of Issus inflation throughout Greece 332 Alexander deifies himself at Siwa in Egypt 395-387 Corinthian War Alex personally outlines Alexandria 371 Battle of Leuctra 331 Battle of Gaugamela Thebes becomes dominant 330 Alex occupies Persepolis 359-336 Reign of Philip II of Macedon 326 Battle of Hydaspes River 336 Alexander assumes the throne (farthest extent of conquest) 324 Alex returns of Babylon 323 Alexander the Great dies wars between the Successors breaks out Star Terms: Geog. Terms: Phillip II Macedonia Alexander the Great Persian Empire Aristotle Hindu Kush A. Battle of Issus (Pompeii), Roman mosaic of a of ca. 310 BCE Greek painting Tactics of Alexander; Roman ability with tessera; their love of Alexander’s heroism and stories; http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/b/b9/Battle_of_Issus_roman_mosaic_from_Pompei.jpg Lecture 8 Alexander B. Demosthenes, Roman copy after a bronze original of c. 280 BCE, marble using art to capture a likeness and personality/ Demosthenes/ realistic depiction vs. an idealized one This statue was one of several Athenian heroes opposed to the Macedonian rule of Athens that was set up in the agora, or marketplace, of the city. Demosthenes was forced by the Macedonians to flee Athens. When he reached the island of Poros, he drank poison rather than submit to the enemy. An inscription on the base of the sculpture reads: ‘If your strength had equaled your resolution, Demosthenes, the Macedonian Ares [i.e. -

Topic Christian View Importance Impact on Christians Today The

Knowledge Organiser– Christian Beliefs Topic Christian View Importance Impact on Christians Today The Trinity * The Trinity is the belief that God is three * The Trinity is important as it shows the oneness * Christians use the Trinity to guide their worship and things in one, God the Father, Son and Holy of God – he is the Creator, Saviour and Guide belief – they can call on any part of God for help Spirit * The Nicene Creed is a statement from the * They can be inspired by the loving relationship Church confirming the Trinity * Christians are baptised in the name of the Trinity Creation *Creationist Christians believe the world was * Creation is important to Christians as they * It is important that Christians today are stewards of created in 6 actual days by God believe the Trinity was present - Jesus was the the Earth and look after and protect Gods creation *Liberal Christians believe God created the Word and the Holy Spirt was there to protect * Christians also have a duty to have children and world by the Big Bang *Creation shows Gods power/ love for humans populate the Earth The * Christians believe that Jesus Christ is the * Jesus came to this world to build a relationship * Christians believe that Jesus understands humans and Incarnation Son of God and came down to Earth in with humans our problems – he can sympathise with us and human form * It shows God loves the world and everyone in it understand our suffering The Last Days * Key events include, The Last Supper, * They teach of Jesus’s last actions and of Gods * Christians follow Jesus’s examples in life and death – of Jesus Life Betrayal, Arrest, Trial, Crucifixion, power and plan for humanity he taught them how to have a relationship with God Resurrection and Ascension * They also show Jesus as a role model for others through love and worship Salvation * Salvation is the belief that Jesus died for * It means everything Jesus taught is true * Christians believe that Jesus’s death allows them to our sins. -

Pausanias' Description of Greece

BONN'S CLASSICAL LIBRARY. PAUSANIAS' DESCRIPTION OF GREECE. PAUSANIAS' TRANSLATED INTO ENGLISH \VITTI NOTES AXD IXDEX BY ARTHUR RICHARD SHILLETO, M.A., Soiiii'tinie Scholar of Trinity L'olltge, Cambridge. VOLUME IT. " ni <le Fnusnnias cst un homme (jui ne mnnquo ni de bon sens inoins a st-s tlioux." hnniie t'oi. inais i}iii rn>it ou au voudrait croire ( 'HAMTAiiNT. : ftEOROE BELL AND SONS. YOUK STIIKKT. COVKNT (iAKDKX. 188t). CHISWICK PRESS \ C. WHITTINGHAM AND CO., TOOKS COURT, CHANCEKV LANE. fA LC >. iV \Q V.2- CONTEXTS. PAGE Book VII. ACHAIA 1 VIII. ARCADIA .61 IX. BtEOTIA 151 -'19 X. PHOCIS . ERRATA. " " " Volume I. Page 8, line 37, for Atte read Attes." As vii. 17. 2<i. (Catullus' Aft is.) ' " Page 150, line '22, for Auxesias" read Anxesia." A.-> ii. 32. " " Page 165, lines 12, 17, 24, for Philhammon read " Philanimon.'' " " '' Page 191, line 4, for Tamagra read Tanagra." " " Pa ire 215, linu 35, for Ye now enter" read Enter ye now." ' " li I'aijf -J27, line 5, for the Little Iliad read The Little Iliad.'- " " " Page ^S9, line 18, for the Babylonians read Babylon.'' " 7 ' Volume II. Page 61, last line, for earth' read Earth." " Page 1)5, line 9, tor "Can-lira'" read Camirus." ' ; " " v 1'age 1 69, line 1 , for and read for. line 2, for "other kinds of flutes "read "other thites.'' ;< " " Page 201, line 9. for Lacenian read Laeonian." " " " line 10, for Chilon read Cliilo." As iii. 1H. Pago 264, " " ' Page 2G8, Note, for I iad read Iliad." PAUSANIAS. BOOK VII. ACIIAIA. -

Basilica Santa Maria Assunta in Torcello, Italy

HADES AS THE RULER OF THE DAMNED IN THE MOSAIC COMPLEX ON THE WEST WALL OF BASILICA SANTA MARIA ASSUNTA IN TORCELLO, ITALY ALEKSANDRA KRAUZE-KOŁODZIEJ The aim of this article is to show the figure of the ancient god Hades as an important part of Byzantine symbolic representations of the Last Judgement, using the example of the mosaic from the west wall of Basilica Santa Maria Assunta in Torcello, Italy. The article is divided into three main parts. The first part briefly introduces the mosaic complex from Torcello, providing a description of the place, the Basilica, and the mosaic. In the second part, the author focuses on the fragment of the mosaic presenting the figure of Hades in hell. In an effort to show the iconographical and cultural continuity between ancient and early medieval representations, the author compares this figure to its ancient prototype. The last part of the article portrays the development of the motif of the Last Judgment by looking at other chosen representations. In conclusion, the author proposes a possible meaning of the presence of Hades in the mosaic of Torcello. Introduction “There [in Hades] also among the dead, so men tell, another Zeus [Haides] holds a last judgment upon misdeeds” (Aeschyl. Suppl. 230).1 Thus, the Greek tragedian describes one of the most mysterious and terrifying gods in the ancient world: Hades, the god of death. Although this mighty divinity already ruled the ancient Greek Underworld in the time of Homer (e.g. Hom. Il. 9,457; Hes. Theog. 455), he did not receive the power to judge the dead until the post-Homeric period (e.g. -

The Afterlife

The Afterlife Comprehension Questions Part 1: Islam Step 1. Separate the letter chain into ten individual words in the spaces provided. Step 2. Complete these statements about Islam by inserting the correct terms from the word bank in the spaces: resurrectedtemporarydeterminedheavendeathAllahquestionssixprayersgrave 1. There are ____________ primary articles of faith in Islam. 2. One of them is that there is life after _____________. 3. Islamic religion teaches that what happens after death is _______________ by what we do in this life. 4. There is a time after death when we will wait in the _______________. 5. Muslims believe that they will face some ______________ whilst in their graves after death. 6. Muslims believe that the current world is only ___________________. 7. In Islam, the goal is to please ____________ while we are alive and thereby gain a fulfilling eternity. 8. The ultimate place of spiritual fulfilment is __________________, according to Islamic religion. 9. Islam teaches that there will be a judgement to determine how well each Muslim has done their ______________. 10. The judgement of humankind, according to Islam, will occur after people have been ___________________. Select the correct word to complete each statement: 11. There are two _______ of accountability in Islamic courts gods theology. 12. The deeds of Muslims are ____________ on written in the weighed on Judgement Day. Quran the scales 13. Muslims believe they will also be judged on whether wronged other spent money they have ________. people wisely 14. To obtain an eternal reward in Islamic religion, work their way accept a Muslims must ____________. to heaven free gift of salvation 15. -

The Bacchae of Euripides

The Bacchae of Euripides By Wole Soyinka Directed by Prof. Judyie Al-Bilali Dramaturgy by Prof. Megan Lewis STUDY GUIDE Contact: Prof Megan Lewis [email protected] DIRECTOR’S NOTE Dionysus and his magnificent initiates, the Bacchantes, have come back for me. I met them twenty years ago when I directed this same adaptation by distinguished Nigerian Nobel Laureate, Wole Soyinka. I embraced his vision as it foregrounds the social and political transformations inherent to the ancient drama, and now two decades later, Soyinka’s script rings even more true as we face unprecedented environmental, ecological, and spiritual challenges. A play is relevant after 2,400 years because it illuminates primal forces, notable among them, sexuality. Dionysus, called by many names including ‘The Liberator’ has often symbolized gender fluidity. In the rigid caste system of ancient Greece, his devotees included slaves, women, and foreigners -- allowing those usually excluded to participate in the annual Dionysian festivals. Our play is set in 2020, just across the threshold into the upcoming decade, at the pivot point of a new era in human history. Our location is Gaia, the mythological Greek name recognizing our beloved and beleaguered planet Earth as a sentient, living goddess. Right now, Gaia demands our attention. She calls us beyond ideology to unity, a call we must heed for our survival as a species. Myth is how we navigate and ultimately evolve both individual and collective psyches. Myth must change for us to grow. Artists are the antennae for society and we are re-imagining Euripides’ myth of Dionysus to address our need for balance between reason and passion.