Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Court and Spark by Sean Nelson Court and Spark by Sean Nelson

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

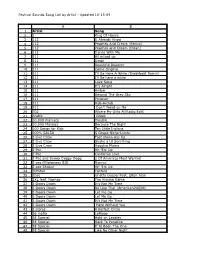

FS Master List-10-15-09.Xlsx

Festival Sounds Song List by Artist - Updated 10-15-09 A B 1 Artist Song 2 1 King Of House 3 112 U Already Know 4 112 Peaches And Cream (Remix) 5 112 Peaches and Cream [Clean] 6 112 Dance With Me 7 311 All mixed up 8 311 Down 9 311 Beautiful Disaster 10 311 Come Original 11 311 I'll Be Here A While (Breakbeat Remix) 12 311 I'll Be here a while 13 311 Love Song 14 311 It's Alright 15 311 Amber 16 311 Beyond The Grey Sky 17 311 Prisoner 18 311 Rub-A-Dub 19 311 Don't Tread on Me 20 702 Where My Girls At(Radio Edit) 21 Arabic Greek 22 10,000 maniacs Trouble 23 10,000 Maniacs Because The Night 24 100 Songs for Kids Ten Little Indians 25 100% SALSA S Grupo Niche-Lluvia 26 2 Live Crew Face Down Ass Up 27 2 Live Crew Shake a Lil Somthing 28 2 Live Crew Hoochie Mama 29 2 Pac Hit 'Em Up 30 2 Pac California Love 31 2 Pac and Snoop Doggy Dogg 2 Of Americas Most Wanted 32 2 pac f/Notorious BIG Runnin' 33 2 pac Shakur Hit 'Em Up 34 20thfox Fanfare 35 2pac Ghetto Gospel Feat. Elton John 36 2XL feat. Nashay The Kissing Game 37 3 Doors Down It's Not My Time 38 3 Doors Down Be Like That (AmericanPieEdit) 39 3 Doors Down Let me Go 40 3 Doors Down Let Me Go 41 3 Doors Down It's Not My Time 42 3 Doors Down Here Without You 43 3 Libras A Perfect Circle 44 36 mafia Lollipop 45 38 Special Hold on Loosley 46 38 Special Back To Paradise 47 38 Special If Id Been The One 48 38 Special Like No Other Night Festival Sounds Song List by Artist - Updated 10-15-09 A B 1 Artist Song 49 38 Special Rockin Into The Night 50 38 Special Saving Grace 51 38 Special Second Chance 52 38 Special Signs Of Love 53 38 Special The Sound Of Your Voice 54 38 Special Fantasy Girl 55 38 Special Caught Up In You 56 38 Special Back Where You Belong 57 3LW No More 58 3OH!3 Don't Trust Me 59 4 Non Blondes What's Up 60 50 Cent Just A Lil' Bit 61 50 Cent Window Shopper (Clean) 62 50 Cent Thug Love (ft. -

January 20, 2006 | Section Three Chicago Reader | January 20, 2006 | Section Three 5

4CHICAGO READER | JANUARY 20, 2006 | SECTION THREE CHICAGO READER | JANUARY 20, 2006 | SECTION THREE 5 [email protected] The Meter www.chicagoreader.com/TheMeter The Treatment A day-by-day guide to our Critic’s Choices and other previews friday 20 Astronomer THE ASTRONOMER Multi-instrumentalist Charles Kim—the architect behind the deeply cinematic Pinetop Seven and Sinister Luck Ensemble—adds his vocals to the mix in his latest group, the Astronomer. But on the band’s eponymous self-released debut, his pedestrian singing lacks the supple, atmospheric quality of his guitar and pedal steel, NI diluting the effect of the spectral music: Kim played nearly TAT everything on the record, and the songs have a gentle, hovering beauty, but on the whole they sound lifeless. Hopefully he’ll get a spark from the musicians joining him here: Steve Dorocke (pedal steel), Jason Toth (drums), John TE MARIE DOS ET Abbey (upright bass), Jeff Frehling (accordion, guitar), and Emmett Kelly YV Tim Joyce (banjo). This show is a release party. The New Messengers of Happiness open. a 10 PM, Hideout, 1354 W. Wabansia, 773-227-4433, $8. —Peter Margasak BOUND STEMS These tuneful local indie rockers recently released their second EP, The Logic of Building the The Long Layover Body Plan (Flameshovel), a teaser for the forthcoming full- length Appreciation Night. Which label will release the LP is still up in the air: as Bob Mehr reported back in November, Guitarist Emmett Kelly liked Chicago so much he never finished his trip. the Bound Stems have attracted the interest of major indies like Domino and Barsuk. -

The Official Publication of Lakeside Yacht Club 4851 North Marginal

Volume 88, Issue 8 August 1, 2018 NOTICE TO MARINERS The Official Publication of Lakeside Yacht Club 4851 North Marginal Road INSIDE THIS ISSUE: Cleveland,Commodore’s Letter Ohio 44114 www.lakesideyachtclub.com Commodore’s 1 Letter Monthly Events 2 Dear LYC Members: Taco Tuesday 3 I’d like to thank Rick Schultz, Garry Marquiss and Capt. Doug Keith for Book Club 5 assembling the dock staff and researching and printing a fueling procedures Nominating 6 and boat docking SAFETY Manuel. On Tuesday they conducted a review and training session on proper fueling and boat handling procedures at the N-Dock Party 8 Fuel Dock. August bands 10 Members; the absolute main reason for this review and training is for your SAFETY, the dock hands SAFETY and the SAFETY of our LYC physical plant. We will be adding some new more visible signage and an August Birthday’s instructional hand out at the fuel dock to clarify fueling procedures. Also 1st for you and your boat’s safety please call the Gas House on your radio, Channel 9, when you need a dock hand to assist you when docking. Please Sunny Klein Lurie identify yourself, your boat and your dock number when calling. When there are multiple boats on multiple docks you may be asked to hold your 3rd position until a dock hand is available. Nicole Boddy REMEMBER to make a reservation at the club to help Larry properly staff 5th the bar, deck and dining room which will result in prompt service and a Pat Quinn more enjoyable experience for you, your guest and our staff. -

HD One Sheet.Indd

Little By Little... “Harvey Danger are too smart to die.” – Spin “Get past the tags other people put on Harvey Danger.” – Pitchforkmedia.com We are proud to announce the third full-length by Seattle’s Harvey Danger. Little By Little... marks the end of the band’s studio hiatus after one of the most dramatic whirlwind success stories of the late ‘90s. Most listeners will be familiar with HD’s gold-selling debut LP, Where Have All The Merrymakers Gone? (Slash/London), which spawned the #1 single and MTV/alt rock radio perennial “Flagpole Sitta.” Many may also remember the much- loved, if little-heard cult follow-up, King James Version (London-Sire). Little By Little... is the sound of a radically • Produced in Seattle, February 2005, by John transformed band. Goodmanson (Sleater-Kinney, Blonde Redhead) and Steve The distorted energy of the original incarnation has been Fisk (Nirvana, Low, Beat Happening, Screaming Trees). replaced by a classic pop sensibility—a fuller, more •Heavy radio airplay at KEXP (www.kexp.org) and KNDD piano-driven sound in place of the caustic alt-garage in Seattle. style that characterized their debut. (Don’t worry, it still rocks.) The new stuff is a bit more Coldplay than Green • Strong web presence planned, including a free down- Day, perhaps, but neither comparison does justice to loadable version of the album at www.harveydanger.com. the intelligent lyrics and startling melodies of Harvey • Deluxe packaging on includes free 30-minute EP Bonus Danger. Little By Little... is a testament to the band’s Disc, for the price of a single album. -

Central Florida Future, April 22, 1998

University of Central Florida STARS Central Florida Future University Archives 4-28-1998 Central Florida Future, April 22, 1998 Part of the Mass Communication Commons, Organizational Communication Commons, Publishing Commons, and the Social Influence and oliticalP Communication Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/centralfloridafuture University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the University Archives at STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Central Florida Future by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Recommended Citation "Central Florida Future, April 22, 1998" (1998). Central Florida Future. 1450. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/centralfloridafuture/1450 A DIGITAL CITY ORLANDO C 0 M M U N I T Y P A R T N E R (AOL Keyword: Orlando) www.UCFFuture.com Reception held to get to know the dean • By DAN McMuLLAN Association (SGA) and the educa SGA allocated~ the funds after Staff Writer tion student ~ean's advisory council McDonald's suggestion for the hosted the event. event. The College of Education A Meet the Dean reception was Education Sen. Joe Sarrubbo said supported the suggestion. The advi Comedian.Jim h_eld for Dean Sandra Robinson, the idea was the inspiration of SGA sory council then organized the ·Breuer entertaf.tl$,, College of Education, on April 22. President Keith McDonald. event. .. 'a crocwct.ofpeo,»li The reception was in the Key · "Keith has wanted to do this, so Kathleen Schilling, president of at the l.JC)!!;tenfJ West room of the Student Union. -

Eastern News: November 03, 2000 Eastern Illinois University

Eastern Illinois University The Keep November 2000 11-3-2000 Daily Eastern News: November 03, 2000 Eastern Illinois University Follow this and additional works at: http://thekeep.eiu.edu/den_2000_nov Recommended Citation Eastern Illinois University, "Daily Eastern News: November 03, 2000" (2000). November. 3. http://thekeep.eiu.edu/den_2000_nov/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the 2000 at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in November by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Daily Friday Vol. 85 No. 54 November 3, 2000 Eastern News www.eiu.edu/~den “Tell the truth and don’t be afraid.” News News Sports Eastern and UPI tentatively Jam band The Station plays Panther football team looks to agree to six-point increase. Marty’s Friday. rebound with a conference home game against SEMO. Story on Page 3 Story on Page 1b Story on Page 8 ‘Live life with love rather than hate’ Registration More than 700 attend Shepard’s for classes heart-wrenching speech Thursday via Web site By Karen Kirr Staff writer increasing A profound energy filled the Martin Luther King Jr. University Union’s Grand Ballroom, which By Karen Kirr well exceeded its capacity, as Judy Staff writer Shepard delivered an emotionally- charged speech about her late son, Eastern’s continuous technology advances during Matthew. the last year have allowed students a convenient way “My goal in speaking to colleges to not only access their grades through the Internet, is to tell them we should be living but also to register for their spring semester courses our life with love rather than hate,” through the Panthers Access to Web Services system Shepard said. -

Popular Song Recordings and the Disembodied Voice

Lipsynching: Popular Song Recordings and the Disembodied Voice Merrie Snell Doctor of Philosophy School of Arts and Cultures April 2015 Abstract This thesis is an exploration and problematization of the practice of lipsynching to pre- recorded song in both professional and vernacular contexts, covering over a century of diverse artistic practices from early sound cinema through to the current popularity of vernacular internet lipsynching videos. This thesis examines the different ways in which the practice provides a locus for discussion about musical authenticity, challenging as well as re-confirming attitudes towards how technologically-mediated audio-visual practices represent musical performance as authentic or otherwise. It also investigates the phenomenon in relation to the changes in our relationship to musical performance as a result of the ubiquity of recorded music in our social and private environments, and the uses to which we put music in our everyday lives. This involves examining the meanings that emerge when a singing voice is set free from the necessity of inhabiting an originating body, and the ways in which under certain conditions, as consumers of recorded song, we draw on our own embodiment to imagine “the disembodied”. The main goal of the thesis is to show, through the study of lipsynching, an understanding of how we listen to, respond to, and use recorded music, not only as a commodity to be consumed but as a culturally-sophisticated and complex means of identification, a site of projection, introjection, and habitation, -

10,000 Maniacs Beth Orton Cowboy Junkies Dar Williams Indigo Girls

Madness +he (,ecials +he (katalites Desmond Dekker 5B?0 +oots and Bob Marley 2+he Maytals (haggy Inner Circle Jimmy Cli// Beenie Man #eter +osh Bob Marley Die 6antastischen BuBu Banton 8nthony B+he Wailers Clueso #eter 6oA (ean #aul *ier 6ettes Brot Culcha Candela MaA %omeo Jan Delay (eeed Deichkind 'ek181Mouse #atrice Ciggy Marley entleman Ca,leton Barrington !e)y Burning (,ear Dennis Brown Black 5huru regory Isaacs (i""la Dane Cook Damian Marley 4orace 8ndy +he 5,setters Israel *ibration Culture (teel #ulse 8dam (andler !ee =(cratch= #erry +he 83uabats 8ugustus #ablo Monty #ython %ichard Cheese 8l,ha Blondy +rans,lants 4ot Water 0ing +ubby Music Big D and the+he Mighty (outh #ark Mighty Bosstones O,eration I)y %eel Big Mad Caddies 0ids +able6ish (lint Catch .. =Weird Al= mewithout-ou +he *andals %ed (,arowes +he (uicide +he Blood !ess +han Machines Brothers Jake +he Bouncing od Is +he ood -anko)icDescendents (ouls ')ery +ime !i/e #ro,agandhi < and #elican JGdayso/static $ot 5 Isis Comeback 0id Me 6irst and the ood %iddance (il)ersun #icku,s %ancid imme immes Blindside Oceansi"ean Astronaut Meshuggah Con)erge I Die 8 (il)er 6ear Be/ore the March dredg !ow $eurosis +he Bled Mt& Cion 8t the #sa,, o/ 6lames John Barry Between the Buried $O6H $orma Jean +he 4orrors and Me 8nti16lag (trike 8nywhere +he (ea Broadcast ods,eed -ou9 (,arta old/inger +he 6all Mono Black 'm,eror and Cake +unng &&&And -ou Will 0now Us +he Dillinger o/ +roy Bernard 4errmann 'sca,e #lan !agwagon -ou (ay #arty9 We (tereolab Drive-In Bi//y Clyro Jonny reenwood (ay Die9 -

Seattle 100: Portrait of a City

Seattle100 PORTRAIT OF A CITY PHOTOGRAPHS & WORDS BY CHASE JARVIS For Kate Seattle100 PORTRAIT OF A CITY New Riders 1249 Eighth Street Berkeley, CA 94710 510/524-2178 510/524-2221 (fax) Find us on the web at www.newriders.com To report errors, please send a note to [email protected] New Riders is an imprint of Peachpit, a division of Pearson Education Copyright 2011 © by Chase Jarvis All book photographs © Chase Jarvis Artist bio photo © Mitch Moquin Editor: Ted Waitt Production Editor: Lisa Brazieal Interior Design: Lou Maxon Indexer: James Minkin Cover Design: Lou Maxon Cover Images: Chase Jarvis Notice of Rights All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. For information on getting permission reprints and excerpts, contact [email protected]. Notice of Liability The information in this book is distributed on an “As Is” basis without warranty. While every precaution has been taken in the preparation of the book, neither the author nor Peachpit shall have any liability to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damage caused or alleged to be caused directly or indirectly by the instructions contained in this book or by the computer software and hardware products described in it. Trademarks Many of the designations used by manufacturers and sellers to distinguish their products are claimed as trademarks. Where those designations appear in this book, and Peachpit was aware of a trademark claim, the designations appear as requested by the owner of the trademark. -

UNIVERSAL MUSIC • Various Aritsts – American Girl Fanzine

Various Aritsts – American Girl Fanzine Soundtrack – Begin Again (Deluxe) Jesse McCartney – In Technicolor New Releases From Classics And Jazz Inside!!! And more… UNI14-27 UNIVERSAL MUSIC 2450 Victoria Park Ave., Suite 1, Willowdale, Ontario M2J 5H3 Phone: (416) 718.4000 Artwork shown may not be final UNIVERSAL MUSIC CANADA NEW RELEASE Artist/Title: ERIC CLAPTON / THE BREEZE: AN APPRECIATION OF J.J. CALE Cat. #: 554082 Price Code: SP Order Due: July 3, 2014 Release Date: July 29, 2014 File: Rock Genre Code: 37 Box Lot: 25 8 22685 54084 4 Artist/Title: ERIC CLAPTON / THE BREEZE: AN APPRECIATION OF J.J. CALE [2 LP] Cat. #: 559621 Price Code: CL Order Due: July 3, 2014 Release Date: July 29, 2014 File: Rock Genre Code: 37 Box Lot: 25 8 22685 59625 4 Eric Clapton has often stated that JJ Cale is one of the single most important figures in rock history, a sentiment echoed by many of his fellow musicians. Cale’s influence on Clapton was profound, and his influence on many more of today’s artists cannot be overstated. To honour JJ’s legacy, a year after his passing, Clapton gathered a group of like-minded friends and musicians for Eric Clapton & Friends: The Breeze, An Appreciation of JJ Cale scheduled to be released July 29, 2014. With performances by Clapton, Mark Knopfler, John Mayer, Willie Nelson, Tom Petty, Derek Trucks and Don White, the album features 16 beloved JJ Cale songs and is named for the 1972 single “Call Me The Breeze.” 1. Call Me The Breeze (Vocals Eric Clapton) TRACKLISTING 9. -

THIS # WEEK CHANCELLOR/See Page

JANUARY 29, 1999 I N S I D E 500 Jobs Lost In Initial Phase Of Universal Restructuring BY STEVE WONSIEWICZ Anderle, Sr. VP /Creative Servic- management c marketing sales R &R MUSIC EDITOR es Jeri Heiden, Sr. VP/Publicity Baron, Sr. VP/Marketing WRTS /Erie, PA Promotion Dir. Matt The reality of consolidation in Diana & Artist Development Morty Sharer has been in the radio business for the record industry hit home last the ini- Wiggins, Sr. VP/Urban Promo- a grand total of one month. While the week, as Seagram began an- tion Dave Rosas and Sr. VP/Pro- circumstances of his getting his job are tial phase of its previously of the motion Peter Napoliello. Key interesting (you can read about it in the nounced restructuring Universal Music Group. Over A &M personnel who remain are story), he now has to put up or shut up. a two -day period, Universal fur- New York -based VP /Publicity To help him get a running start, MMS loughed some 500 employees, Steve Karas; Los Angeles -based Editor Jeff Axelrod paired Matt up with with the biggest cuts occurring at VP/Publicity Laura Swanson; Sr. WKTU /NY Dir. /Marketing Don Macleod for A &M Records (about 170 of VP /Sales & Distribution Richie mentoring. Jeff some one -on -one 200 employees were let go) and Gallo, who will assume a cata- eavesdropped on the conversation, and Geffen Records (110), as the log post at Universal Music & you can read the first part of a two -part Chancellor Goes On The Block company folds the two legendary Video Distribution; and Sr. -

Reviews & Previews

Reviews & Previews S P O T L I G H T S P O T L I G H T S P O T L I G H T TAKE ME TO THE RIVER third -degree burns, and then shot By Al Green with Davin Seay herself. HarperCollins Despite the many indispensable 343 pages; $25 charms of "Take Me To The River" THE BROTHERS (penned with hip -hop journalist By Art, Aaron. Charles, and Cyril Neville with David Davin Seay), the book disappoints Ritz as it dissipates near the end. Little, Brown 368 pages; $24.95 Green insists that it isn't true that "the best part of my life was over" Two founts of Southern soul music when he gave up secular singing, SEAL This Could Be Heaven (no timing listed) PINK You Make Me Sick 14:10) ELTON JOHN FEATURING MARY J. BLIGE I Guess have finally told their tales, and yet his thin treatment of his years PRODUCERS: Seal, Henry Jackman PRODUCERS: Babyface, Anthony President, Brainz That's Why They Call It The Blues (4:30) there are similarities in the paths after 1975 does beg the question. WRITERS: D. Palmer, H. Jackman, G. Dimilo Seal, Gersoni PRODUCER: Darryl Simmons recount ties and of worse, the book has been PUBLISHER: not listed WRITERS: A. President, B. Dìmìlo, M. Tabb WRITERS: E. John, B. Taupin, D. Johnstone they -the tears Far hap- Sire Records (CD promo) PUBLISHERS: Me & Chumba Music /E2 /EMI, Ainz- PUBLISHERS: Publishing Happenstance family, the wages of sin and the balm hazardly produced, with few pho- Seal, a consistent top 40 /AC mainstay worth Amil Music/Woodfella Music, ASCAP Ltd.