Onetouch 4.0 Scanned Documents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mammal Collections Accredited by the American Society of Mammalogists, Systematics Collections Committee

MAMMAL COLLECTIONS ACCREDITED BY THE AMERICAN SOCIETY OF MAMMALOGISTS The collections on this list meet or exceed the basic curatorial standards established by the ASM Systematic Collections Committee (Appendix V). Collections are listed alphabetically by country, then province or state. Date of accreditation (and reaccreditation) are indicated. Year of Province Collection name and acronym accreditation or state ARGENTINA Universidad Nacional de Tucumán, Colección de Mamíferos Lillo (CML) 1999 Tucumán CANADA Provincial Museum of Alberta (PMA) 1985 Alberta University of Alberta, Museum of Zoology (UAMZ) 1985 Alberta Royal British Columbia Museum (RBCM) 1976 British Columbia University of British Columbia, Cowan Vertebrate Museum (UBC) 1975 British Columbia Canadian Museum of Nature (CMN) 1975, 1987 Ontario Royal Ontario Museum (ROM) 1975, 1995 Ontario MEXICO Colección Nacional de Mamíferos, Instituto de Biología, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (CNMA) 1975, 1983 Distrito Federal Centro de Investigaciones Biologicas del Noroeste (CIBNOR) 1999 Baja California Sur UNITED STATES University of Alaska Museum (UAM) 1975, 1983 Alaska University of Arizona, Collection of Mammals (UA) 1975, 1982 Arizona Arkansas State University, Collection of Recent Mammals (ASUMZ) 1976 Arkansas University of Arkansas at Little Rock (UALRVC) 1977 Arkansas California Academy of Sciences (CAS) 1975 California California State University, Long Beach (CSULB) 1979, 1980 California Humboldt State University (HSU) 1984 California Natural History Museum of Los -

1 VERTEBRATE ZOOLOGY (BIO 353) Spring 2019 MW 8:45-10:00 AM, 207 Payson Smith Lab: M 11:45-3:35 PM, 160 Science INSTRUCTOR

VERTEBRATE ZOOLOGY (BIO 353) Spring 2019 MW 8:45-10:00 AM, 207 Payson Smith Lab: M 11:45-3:35 PM, 160 Science INSTRUCTOR: Dr. Chris Maher EMAIL: [email protected] OFFICE LOCATION: 201 Science (A Wing) or 178 Science (CSTH Dean’s office, C Wing) OFFICE PHONE: 207.780.4612; 207.780.4377 OFFICE HOURS: T 12:00 – 1:00 PM, W 10:00 AM – 12:00 PM, or by appointment I usually hold office hours in 201 Science; however, if plans change, I leave a note on the door, and you probably can find me in 178 Science. Office hours are subject to change due to my meeting schedule, and I try to notify you in advance. COURSE DESCRIPTION: Vertebrate Zoology is an upper division biology elective in Area 1 (Organismal Biology) that surveys major groups of vertebrates. We examine many aspects of vertebrate biology, including physiology, anatomy, morphology, ecology, behavior, evolution, and conservation. This course also includes a laboratory component, the primary focus of which will be a survey of vertebrates at a local natural area. As much as possible, we will spend time in the field, learning survey techniques and identifying vertebrates. This syllabus is intended as a guide for the semester; however, I reserve the right to make changes in topics or schedules as necessary. COURSE PREREQUISITES: You must have successfully completed (i.e., grade of C- or higher) Biological Principles III (BIO 109). Although not required, courses in evolution (BIO 217), ecology (e.g., BIO 203), and animal physiology (e.g., BIO 401) should prove helpful. -

Coversheet for Thesis in Sussex Research Online

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Sussex Research Online A University of Sussex PhD thesis Available online via Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/ This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Please visit Sussex Research Online for more information and further details Cuvier in Context: Literature and Science in the Long Nineteenth Century Charles Paul Keeling DPhil English Literature University of Sussex December 2016 I hereby declare that this thesis has not been and will not be, submitted in whole or in part to an- other University for the award of any other degree. Signature:……………………………………… UNIVERSITY OF SUSSEX CHARLES PAUL KEELING DPHIL ENGLISH LITERATURE CUVIER IN CONTEXT: LITERATURE AND SCIENCE IN THE LONG NINETEENTH CENTURY This study investigates the role and significance of Cuvier’s science, its knowledge and practice, in British science and literature in the first half of the nineteenth century. It asks what the current account of science or grand science narrative is, and how voicing Cuvier changes that account. The field of literature and science studies has seen healthy debate between literary critics and historians of science representing a combination of differing critical approaches. -

Zoology Courses 1

Zoology Courses 1 Zoology Courses Courses ZOOL 2406. Vertebrate Zoology. Vertebrate Zoology: A survey of basic classification, functional systems, and biology of vertebrates. MATH 1508 may be taken concurrently with ZOOL 2406. Course fee required. [Common Course Number BIOL 1313] Department: Zoology 4 Credit Hours 6 Total Contact Hours 3 Lab Hours 3 Lecture Hours 0 Other Hours Prerequisite(s): (BIOL 1107 w/D or better AND BIOL 1305 w/D or better ) AND (BIOL 1108 w/D or better AND BIOL 1306 w/D or better) ZOOL 2466. Invertebrate Zoology. Invertebrate Zoology: Survey and laboratory exercises concerning the invertebrates with emphasis on phylogeny. Course fee required. [Common Course Number BIOL 1413] Department: Zoology 4 Credit Hours 6 Total Contact Hours 3 Lab Hours 3 Lecture Hours 0 Other Hours Prerequisite(s): (BIOL 1107 w/D or better AND BIOL 1305 w/D or better ) AND (BIOL 1108 w/D or better AND BIOL 1306 w/D or better) ZOOL 3464. Medical Parasitology. Medical Parasitology (3-3) A survey of medically important parasites. Prerequisite: ZOOL 2406, or BIOL 1306 and BIOL 1108. Lab fee required. Replaced ZOOL 3364 and ZOOL 1365. Department: Zoology 4 Credit Hours 6 Total Contact Hours 3 Lab Hours 3 Lecture Hours 0 Other Hours Prerequisite(s): (ZOOL 2406 w/D or better ) OR (BIOL 1108 w/D or better AND BIOL 1306 w/D or better) ZOOL 4181. Vertebrate Physiology Methods. Vertebrate Physiology Methods (0-3) Techniques and instrumentation used in the study of vertebrate function. Prerequisites: CHEM 1306-1106 or CHEM 1408 and (1) BIOL 1306-1108, (2) BIOL 2313-2113, (3) BIOL 3414, or (4) ZOOL 2406. -

Biblioqraphy & Natural History

BIBLIOQRAPHY & NATURAL HISTORY Essays presented at a Conference convened in June 1964 by Thomas R. Buckman Lawrence, Kansas 1966 University of Kansas Libraries University of Kansas Publications Library Series, 27 Copyright 1966 by the University of Kansas Libraries Library of Congress Catalog Card number: 66-64215 Printed in Lawrence, Kansas, U.S.A., by the University of Kansas Printing Service. Introduction The purpose of this group of essays and formal papers is to focus attention on some aspects of bibliography in the service of natural history, and possibly to stimulate further studies which may be of mutual usefulness to biologists and historians of science, and also to librarians and museum curators. Bibli• ography is interpreted rather broadly to include botanical illustration. Further, the intent and style of the contributions reflects the occasion—a meeting of bookmen, scientists and scholars assembled not only to discuss specific examples of the uses of books and manuscripts in the natural sciences, but also to consider some other related matters in a spirit of wit and congeniality. Thus we hope in this volume, as in the conference itself, both to inform and to please. When Edwin Wolf, 2nd, Librarian of the Library Company of Phila• delphia, and then Chairman of the Rare Books Section of the Association of College and Research Libraries, asked me to plan the Section's program for its session in Lawrence, June 25-27, 1964, we agreed immediately on a theme. With few exceptions, we noted, the bibliography of natural history has received little attention in this country, and yet it is indispensable to many biologists and to historians of the natural sciences. -

The Linnaean Collections

THE LINNEAN SPECIAL ISSUE No. 7 The Linnaean Collections edited by B. Gardiner and M. Morris WILEY-BLACKWELL 9600 Garsington Road, Oxford OX4 2DQ © 2007 The Linnean Society of London All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. The designations of geographic entities in this book, and the presentation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the publishers, the Linnean Society, the editors or any other participating organisations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The Linnaean Collections Introduction In its creation the Linnaean methodology owes as much to Artedi as to Linneaus himself. So how did this come about? It was in the spring of 1729 when Linnaeus first met Artedi in Uppsala and they remained together for just over seven years. It was during this period that they not only became the closest of friends but also developed what was to become their modus operandi. Artedi was especially interested in natural history, mineralogy and chemistry; Linnaeus on the other hand was far more interested in botany. Thus it was at this point that they decided to split up the natural world between them. Artedi took the fishes, amphibia and reptiles, Linnaeus the plants, insects and birds and, while both agreed to work on the mammals, Linneaus obligingly gave over one plant family – the Umbelliforae – to Artedi “as he wanted to work out a new method of classifying them”. -

Zoology of Courses

Descriptions -Zoology of Courses ZOOLOGY ZOL :325. Inrertehrate Systematics 404. Biological and Ecological l~aboratory Concepts for Engineers and \Viuter. 2(0-6) ZOL 303. Open to Zool ;\1 at hem a ticia ns College of Human Medicine ogy majors onlu; others: appro1Jal of depart Wi11ter. 3(3-U) ApproJJal of depart College of Natural Science men I. ment. Interdepartmental u:ith Systems Science. Comparative morphology and ta.>..onomy of the Biological and ecological corH:Ppts important to IDC. Introduction to Resource major invertc>brate phyla and an examination of formal analy;,is of livi11g s;,ste111;,, vital prop Ecology their characteristic: behavior and physiology. ertie~, proce;,;,es, and limitations; population dynanlic~, ~eleeti011, competition, and prPrla For course description, see Interdisci tion; c>cological community structure and func plinary Courses. 337. The Fossil Record of Organic tion; industrialized eco s~ stem. Evolution 301. Nature and Homo Sapien~> Spring. 3(3-0) One course in a natural 405H. Experiments in Zoology I Spring. 4(2-6) Three terms of natural science; Juniors. Interdepartmental u;ith and (40.5.) Fall. 4(0-12) Appro~al of in- science; not open to zoologu majors. administ~red h11 the Department of Geofog!J. structor. Relates humans to their natural euvironnwnt. The direct evidence for organic: evolution in the An integrated series of selected e.>..pcriments in Chief empha~b on identifying characteristic fo~sil record. Evolution ot' ]if(; from prc>hiologi the topic;, ofbehaYior, ecolog), JllllTpholog: and animal life in broad areas of nature and how cal systems to nHUL lmpad of fo~sil dhcoYerie~ phy~iology. -

Vertebrate Zoology Zoo 3303 Fall 2017 3 Credits By: Mattie Squire, 2010

Vertebrate Zoology Zoo 3303 Fall 2017 3 credits By: Mattie Squire, 2010 Instructor: Dr. Sarah L. Eddy Class: E-mail: [email protected]** Day/Time: Monday, Wednesday, Friday Office Hour: Monday 12 – 1 pm, 8:00 am – 9:00 am Tuesday 12 – 1 pm, Location: Chemistry & Physics 197 Weds 2 – 3 pm, Friday 9 – 10 am, By appointment Office: OE 215 ** I only check my email weekdays between 9:00 am and 5:00 pm. The Course Overview: Course Purpose: This course integrates multiple biological disciplines (including ecology, genetics, developmental biology, evolution, and physiology) to explore the biology and evolutionary history of vertebrates. We will survey the important theories and hypotheses about the biology of vertebrates and examine how these concepts were conceived and tested. Course Outcomes: Through this course, assuming you fulfill the expectations in this syllabus, you will be able to: 1. Describe the solutions employed by different groups of vertebrates to shared environmental challenges (i.e., adaptations) and explain how these environmental challenges shaped vertebrate morphology and life history. 2. Interpret phylogenies and describe the relationships between different vertebrate groups. 3. Categorize vertebrates by their morphological novelties. 4. Use vertebrate examples to explain ecological, physiological, developmental and evolutionary concepts. 5. Justify how data from scientific studies on vertebrates supports relevant ecological, physiological, developmental, and evolutionary concepts. Text: Pough, Janis and Heiser. 2013. Vertebrate Life. 9th edition. Pearson Prentice Hall Publishing. How to use the Readings: The structure of the lecture is not paralleled by the book. For each lecture you will be directed to read multiple sections from the text. -

Wallace and Savage: Heroes, Theories, and Venomous Snake Mimicry

Wallace and Savage: Heroes, Theories, and Venomous Snake Mimicry Harry W. Greene and Roy W. McDiarmid In the dawn of field biology, Alfred Russel Wallace departed for the most distant and dangerous biotic frontiers of the world, carrying with him little formal education but a blessed love of reading and reflective solitude. He sought the insect-ridden Edens of which naturalist explorers dream. His principal lifeline to the English homeland con- sisted of specimens outbound•birds skinned, insects pinned, plants pressed•and sporadic payments for his treasures inbound. An intense young man, totally focused, awesomely persistent and resourceful, resilient to tropical diseases that might have killed others, and nobly selfless, even to Darwin, who otherwise might have become a bitter rival, Wallace endured, and he triumphed. He succeeded brilliantly because he relished detail while thinking across a wide canvas. E. o. WILSON (1999) Among the Bribri, Cabecar, Boruca, Changina, and Chiriqui, when the chicha has been drunk, the night grows late and dark, and the fires die down to burning embers, the wisest old man of the tribe tells his engrossed listeners of a beautiful miraculous golden frog that dwells in the forests of these mystical mountains. According to the legends, this frog is ever so shy and retiring and can only be found after arduous trials and patient search in the dark woods on fog shrouded slopes and frigid peaks. How- ever, the reward for the finder of this marvelous creature is sublime. Anyone who spies the glittering brilliance of the frog is at first astounded by its beauty and overwhelmed by the excitement and joy of discovery... -

An Update of Wallacels Zoogeographic Regions of the World

REPORTS To examine the temporal profile of ChC produc- specification of a distinct, and probably the last, 3. G. A. Ascoli et al., Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 9, 557 (2008). tion and their correlation to laminar deployment, cohort in this lineage—the ChCs. 4. J. Szentágothai, M. A. Arbib, Neurosci. Res. Program Bull. 12, 305 (1974). we injected a single pulse of BrdU into pregnant A recent study demonstrated that progeni- CreER 5. P. Somogyi, Brain Res. 136, 345 (1977). Nkx2.1 ;Ai9 females at successive days be- tors below the ventral wall of the lateral ventricle 6. L. Sussel, O. Marin, S. Kimura, J. L. Rubenstein, tween E15 and P1 to label mitotic progenitors, (i.e., VGZ) of human infants give rise to a medial Development 126, 3359 (1999). each paired with a pulse of tamoxifen at E17 to migratory stream destined to the ventral mPFC 7. S. J. Butt et al., Neuron 59, 722 (2008). + 18 8. H. Taniguchi et al., Neuron 71, 995 (2011). label NKX2.1 cells (Fig. 3A). We first quanti- ( ). Despite species differences in the develop- 9. L. Madisen et al., Nat. Neurosci. 13, 133 (2010). fied the fraction of L2 ChCs (identified by mor- mental timing of corticogenesis, this study and 10. J. Szabadics et al., Science 311, 233 (2006). + phology) in mPFC that were also BrdU+. Although our findings raise the possibility that the NKX2.1 11. A. Woodruff, Q. Xu, S. A. Anderson, R. Yuste, Front. there was ChC production by E15, consistent progenitors in VGZ and their extended neurogenesis Neural Circuits 3, 15 (2009). -

Spring 2011 Sci150 (Section 2): Vertebrate Zoology

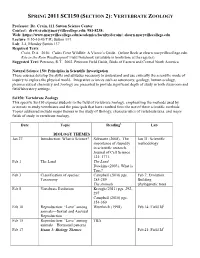

SPRING 2011 SCI150 (SECTION 2): VERTEBRATE ZOOLOGY Professor: Dr. Crain, 111 Sutton Science Center Contact: [email protected]; 981-8238; Web: https://www.maryvillecollege.edu/academics/faculty/dcrain/; elearn.maryvillecollege.edu Lecture: 9:30-10:45 T/R; Sutton 113 Lab: 2-4, Monday Sutton 137 Required Texts: Crain, D.A. 2010. Cades Cove Wildlife: A Visitor’s Guide. Online Book at elearn.maryvillecollege.edu. Rite in the Rain Weatherproof Field Notebook (available in bookstore at the register). Suggested Text: Peterson, R.T. 2002. Peterson Field Guide, Birds of Eastern and Central North America Natural Science 150: Principles in Scientific Investigation These courses develop the skills and attitudes necessary to understand and use critically the scientific mode of inquiry to explore the physical world. Integrative sciences such as astronomy, geology, human ecology, pharmaceutical chemistry and zoology are presented to provide significant depth of study in both classroom and field/laboratory settings. Sci150: Vertebrate Zoology This specific Sci150 exposes students to the field of vertebrate zoology, emphasizing the methods used by scientists to study vertebrates and the principals that have resulted from the use of these scientific methods. Topics addressed include major themes in the study of Biology, characteristics of vertebrate taxa, and major fields of study in vertebrate zoology. Date Topic Reading1 Lab BIOLOGY THEMES Jan 27 Introduction; What is Science? Schwartz (2008). The Jan 31: Scientific importance of stupidity methodology in scientific research. Journal of Cell Science 121: 1771. Feb 1 The Land The Land Dawkins (2003). What is True? Feb 3 Classification of species: Campbell (2010) pgs. -

CUENCA 2021 August 31 to September 2

Joint virtual conference CUENCA 2021 August 31 to September 2 69th WDA th 14 EWDA Instituto de Investigación en Recursos Cinegéticos CSIC - UCLM- JCCM 69th WDA 14th EWDA Joint virtual conference CUENCA 2021 August 31 to September 2 INDEX 03 Welcome letter 04 Invited speakers 06 Committees: Organizer, scientific and reviewer 08 General information 09 Schedule 12 Programme 32 E-posters 2 69th WDA 14th EWDA Joint virtual conference CUENCA 2021 August 31 to September 2 WELCOME to the Virtual 69th WDA /14th EWDA 2021 Joint Conference. This is the 2nd time in history that the “mother” International Wildlife Disease Association (WDA) liaises with the European section (EWDA) to organize a joint Conference that provides members and non-members with the opportunity of exchanging science, expertise, mentoring and good conversations on wildlife health unfortunately not as planned with a coffee, beer or wine in hand, but in a unique and new virtual setting and more than ever with the final goal of better Managing Wildlife Diseases for Sustainable Ecosystems. Although the 69th annual WDA / 14th biennial EWDA Joint Conference had been planned to take place in the beautiful medieval city of Cuenca (Spain) on August 30 - September 3, 2021 it will now be held in a user-friendly online format designed for all of us to get the maximum benefit and insights. Although a Virtual Conference can never fully replace the opportunity to meet friends and colleagues, we have streamlined our Conference to provide a maximum of opportunities for interaction and networking as well as for room for discussion and lots of useful exciting information! The Conference will also advertise parallel activities as the EWDA Wildlife Health Surveillance Network meeting and will try to keep celebrating the traditional Student-Mentor mixer.