Wallace and Savage: Heroes, Theories, and Venomous Snake Mimicry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE SNAKES of SURINAM, PART XVI: SUBFAMILY XENO- By: A

-THE SNAKES -OF SURINAM, ---PART XVI: SUBFAMILY --XENO- DONTINAE ( GENERA WAGLEROPHIS., XENODON AND XENO PHOLIS). By: A. Abuys, Jukwerderweg 31, 9901 GL Appinge dam, The Netherlands. Contents: The genus WagZerophis - The genus Xeno don - The genus XenophoZis - References. THE GENUS wAGLEROPHIS ROMANO & HOGE, 1972 This genus contains only one species. Prior to 1972 this species was known as Xenodon merremii (Wagler, 1824). This species is found in Surinam. General data for the genus: Head: The head is short and slightly flattened. The strong neck is only marginally narrower than the head. The relatively large eyes have round pupils. Body: Short and stout with smooth scales. The scales have one apical groove. The formation of the dorsal scales is characteristic for this genus. These are arranged so that the upper rows are at an angle to the lower ones (see figure 1) . Tail: Short. Behaviour: Terrestrial and both nocturnal and di urnal. Food: Frogs, toads, lizards and sometimes snakes, insects or small mammals. Habitat: Damp forest floors near swamps or water. Reproduction: Oviparous. Remarks: When threatened or disturbed, the fore part of the body is inflated and the neck is spread in a cobra-like fashion. The head is al· so raised slightly, but not as high and as 181 Fig. 1. Dorsal scale pattern of Waglerophis. From: Peters & Orejas-Miranda, 1970. vertically as a cobra. This is an aggressive snake which will invariably resort to biting if the warning behaviour described above is not heeded. This genus (in common with the genera Xenodon, Heterodon and Lystrophis) has two enlarged teeth attached to the back of the upper jaw. -

William H. Hall High School

WILLIAM H. HALL HIGH SCHOOL WARRIORS Program of Studies 2016-2017 WILLIAM HALL HIGH SCHOOL 975 North Main Street West Hartford, Connecticut 06117 Phone: 860-232-4561 Fax: 860-236-0366 CENTRAL OFFICE ADMINISTRATION Mr. Thomas Moore – Superintendent Mr. Paul Vicinus - Assistant Superintendent Dr. Andrew Morrow – Assistant Superintendent BOARD OF EDUCATION Dr. Mark Overmyer-Velazquez – Chairperson Ms. Tammy Exum – Vice-Chair Ms Carol A Blanks – Secretary Dr. Cheryl Greenberg Mr. Dave Pauluk Mr. Jay Sarzen Mr. Mark Zydanowicz HALL HIGH SCHOOL ADMINISTRATION Mr. Dan Zittoun – Principal Mr. John Guidry - Assistant Principal Dr. Gretchen Nelson - Assistant Principal Ms. Shelley A. Solomon - Assistant Principal DEPARTMENT SUPERVISORS Mrs. Lucy Cartland – World Languages Mr. Brian Cohen – Career & Technical Education Lisa Daly – Physical Education and Health Mr. Chad Ellis – Social Studies Mr. Tor Fiske – School Counseling Mr. Andrew Mayo – Performing Arts Ms. Pamela Murphy – Visual Arts Dr. Kris Nystrom – English and Reading Mr. Michael Rollins – Science Mrs. Patricia Susla – Math SCHOOL COUNSELORS Mrs. Heather Alix Mr. Ryan Carlson Mrs. Jessica Evans Mrs. Amy Landers Mrs. Christine Mahler Mrs. Samantha Nebiolo Mr. John Suchocki Ms. Amanda Williams 1 Table of Contents Administration ............................................................................................................................................. 1 Table of Contents ....................................................................................................................................... -

Mammal Collections Accredited by the American Society of Mammalogists, Systematics Collections Committee

MAMMAL COLLECTIONS ACCREDITED BY THE AMERICAN SOCIETY OF MAMMALOGISTS The collections on this list meet or exceed the basic curatorial standards established by the ASM Systematic Collections Committee (Appendix V). Collections are listed alphabetically by country, then province or state. Date of accreditation (and reaccreditation) are indicated. Year of Province Collection name and acronym accreditation or state ARGENTINA Universidad Nacional de Tucumán, Colección de Mamíferos Lillo (CML) 1999 Tucumán CANADA Provincial Museum of Alberta (PMA) 1985 Alberta University of Alberta, Museum of Zoology (UAMZ) 1985 Alberta Royal British Columbia Museum (RBCM) 1976 British Columbia University of British Columbia, Cowan Vertebrate Museum (UBC) 1975 British Columbia Canadian Museum of Nature (CMN) 1975, 1987 Ontario Royal Ontario Museum (ROM) 1975, 1995 Ontario MEXICO Colección Nacional de Mamíferos, Instituto de Biología, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (CNMA) 1975, 1983 Distrito Federal Centro de Investigaciones Biologicas del Noroeste (CIBNOR) 1999 Baja California Sur UNITED STATES University of Alaska Museum (UAM) 1975, 1983 Alaska University of Arizona, Collection of Mammals (UA) 1975, 1982 Arizona Arkansas State University, Collection of Recent Mammals (ASUMZ) 1976 Arkansas University of Arkansas at Little Rock (UALRVC) 1977 Arkansas California Academy of Sciences (CAS) 1975 California California State University, Long Beach (CSULB) 1979, 1980 California Humboldt State University (HSU) 1984 California Natural History Museum of Los -

The Patagonian Herpetofauna José M

The Patagonian Herpetofauna José M. Cei Instituto de Biología Animal Universidad Nacional de Cuyo Casilla Correo 327 Mendoza, Argentina Reprinted from: Duellman, William E. (ed.). 1979. The South American Herpetofauna: Its origin, evolution, and dispersal. Univ. Kansas Mus. Nat. Hist. MonOgr. 7: 1-485. Copyright © 1979 by The Museum of Natural History, The University of Kansas, Lawrence, Kansas. 13. The Patagonian Herpetofauna José M. Cei Instituto de Biología Animal Universidad Nacional de Cuyo Casilla Correo 327 Mendoza, Argentina The word Patagonia is derived from the longed erosion. Scattered through the region term “Patagones,” meaning big-legged men, are extensive areas of extrusive basaltic rocks. applied to the tall Tehuelche Indians of The open landscape is dissected by transverse southernmost South America by Ferdinand rivers descending from the snowy Andean Magellan in 1520. Subsequently, this pic cordillera; drainage is poor near the Atlantic turesque name came to be applied to a con coast. Patagonia is subjected to severe sea spicuous continental region and to its biota. sonal drought with about five cold winter Biologically, Patagonia can be defined as months and a cool dry summer, infrequently that region east of the Andes and extending interrupted by irregular rains and floods. southward to the Straits of Magellan and eastward to the Atlantic Ocean. The northern boundary is not so clear cut. Elements of the HISTORY OF THE PATAGONIAN BIOTA Pampean biota penetrate southward along the coast between the Rio Colorado and the Rio In contrast to the present, almost uniform Negro (Fig. 13:1). Also, in the west Pata steppe associations in Rio Negro, Chubut, gonian landscapes and biota enter the vol and Santa Cruz provinces, during Oligocene canic regions of southern Mendoza, almost and Miocene times tropical and subtropical reaching the Rio Atuel Basin. -

Heroes (TV Series) - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia Pagina 1 Di 20

Heroes (TV series) - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Pagina 1 di 20 Heroes (TV series) From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Heroes was an American science fiction Heroes television drama series created by Tim Kring that appeared on NBC for four seasons from September 25, 2006 through February 8, 2010. The series tells the stories of ordinary people who discover superhuman abilities, and how these abilities take effect in the characters' lives. The The logo for the series featuring a solar eclipse series emulates the aesthetic style and storytelling Genre Serial drama of American comic books, using short, multi- Science fiction episode story arcs that build upon a larger, more encompassing arc. [1] The series is produced by Created by Tim Kring Tailwind Productions in association with Starring David Anders Universal Media Studios,[2] and was filmed Kristen Bell primarily in Los Angeles, California. [3] Santiago Cabrera Four complete seasons aired, ending on February Jack Coleman 8, 2010. The critically acclaimed first season had Tawny Cypress a run of 23 episodes and garnered an average of Dana Davis 14.3 million viewers in the United States, Noah Gray-Cabey receiving the highest rating for an NBC drama Greg Grunberg premiere in five years. [4] The second season of Robert Knepper Heroes attracted an average of 13.1 million Ali Larter viewers in the U.S., [5] and marked NBC's sole series among the top 20 ranked programs in total James Kyson Lee viewership for the 2007–2008 season. [6] Heroes Masi Oka has garnered a number of awards and Hayden Panettiere nominations, including Primetime Emmy awards, Adrian Pasdar Golden Globes, People's Choice Awards and Zachary Quinto [2] British Academy Television Awards. -

1 VERTEBRATE ZOOLOGY (BIO 353) Spring 2019 MW 8:45-10:00 AM, 207 Payson Smith Lab: M 11:45-3:35 PM, 160 Science INSTRUCTOR

VERTEBRATE ZOOLOGY (BIO 353) Spring 2019 MW 8:45-10:00 AM, 207 Payson Smith Lab: M 11:45-3:35 PM, 160 Science INSTRUCTOR: Dr. Chris Maher EMAIL: [email protected] OFFICE LOCATION: 201 Science (A Wing) or 178 Science (CSTH Dean’s office, C Wing) OFFICE PHONE: 207.780.4612; 207.780.4377 OFFICE HOURS: T 12:00 – 1:00 PM, W 10:00 AM – 12:00 PM, or by appointment I usually hold office hours in 201 Science; however, if plans change, I leave a note on the door, and you probably can find me in 178 Science. Office hours are subject to change due to my meeting schedule, and I try to notify you in advance. COURSE DESCRIPTION: Vertebrate Zoology is an upper division biology elective in Area 1 (Organismal Biology) that surveys major groups of vertebrates. We examine many aspects of vertebrate biology, including physiology, anatomy, morphology, ecology, behavior, evolution, and conservation. This course also includes a laboratory component, the primary focus of which will be a survey of vertebrates at a local natural area. As much as possible, we will spend time in the field, learning survey techniques and identifying vertebrates. This syllabus is intended as a guide for the semester; however, I reserve the right to make changes in topics or schedules as necessary. COURSE PREREQUISITES: You must have successfully completed (i.e., grade of C- or higher) Biological Principles III (BIO 109). Although not required, courses in evolution (BIO 217), ecology (e.g., BIO 203), and animal physiology (e.g., BIO 401) should prove helpful. -

Caderno De Resumos EHFB 2015

Maria Elice Brzezinski Prestes Tatiana Tavares da Silva Rosa Andrea Lopes de Souza (Organizadoras) Anais do Encontro de História e Filosofia da Biologia 2015 São Paulo Instituto de Biociências (IB/USP) 2015 Maria Elice Brzezinski Prestes Tatiana Tavares da Silva Rosa Andrea Lopes de Souza (Organizadoras) Anais do Encontro de História e Filosofia da Biologia 2015 Instituto de Biociências Universidade de São Paulo São Paulo 29 a 31 de julho de 2015 Promoção: ABFHiB, Associação Brasileira de Filosofia e His- tória da Biologia Apoio: Instituto de Biociências da Universidade de São Paulo (IB-USP) Núcleo de Pesquisa em Educação, Divulgação e Epistemologia da Evolução (EDEVO-Darwin) Laboratório de História da Biologia e Ensino (IB-USP) Programa de Pós-Graduação em Ciências Biológicas (Genética e Biologia Evolutiva) do IB-USP Programa de Pós-Graduação Interunidades em Ensino de Ciências da USP Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo (FAPESP) ENCONTRO DE HISTÓRIA E FILOSOFIA DA BIOLOGIA 2015 São Paulo, 29 a 31 de agosto de 2015 LOCAL: Instituto de Biociências da Universidade de São Paulo – Edifício Félix Kurt Rawitsher (“Minas”) PROMOÇÃO: Associação Brasileira de Filosofia e História da Biologia (ABFHiB) http://www.abfhib.org COMISSÃO ORGANIZADORA: Maria Elice Brzezinski Prestes (IB-USP) Nelio Bizzo (FE-USP) Maurício de Carvalho Ramos (FFLCH-USP) Hamilton Haddad (IB-USP) COMISSÃO CIENTÍFICA: Aldo M. de Araújo (Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul) Ana Maria de Andrade Caldeira (Universidade Estadual Paulista) Anna Carolina Regner -

Coversheet for Thesis in Sussex Research Online

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Sussex Research Online A University of Sussex PhD thesis Available online via Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/ This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Please visit Sussex Research Online for more information and further details Cuvier in Context: Literature and Science in the Long Nineteenth Century Charles Paul Keeling DPhil English Literature University of Sussex December 2016 I hereby declare that this thesis has not been and will not be, submitted in whole or in part to an- other University for the award of any other degree. Signature:……………………………………… UNIVERSITY OF SUSSEX CHARLES PAUL KEELING DPHIL ENGLISH LITERATURE CUVIER IN CONTEXT: LITERATURE AND SCIENCE IN THE LONG NINETEENTH CENTURY This study investigates the role and significance of Cuvier’s science, its knowledge and practice, in British science and literature in the first half of the nineteenth century. It asks what the current account of science or grand science narrative is, and how voicing Cuvier changes that account. The field of literature and science studies has seen healthy debate between literary critics and historians of science representing a combination of differing critical approaches. -

Villains, Victims, and Heroes in Character Theory and Affect Control

Social Psychology Quarterly 00(0) 1–20 Villains, Victims, and Heroes Ó American Sociological Association 2018 DOI: 10.1177/0190272518781050 in Character Theory and journals.sagepub.com/home/spq Affect Control Theory Kelly Bergstrand1 and James M. Jasper2 Abstract We examine three basic tropes—villain, victim, and hero—that emerge in images, claims, and narratives. We compare recent research on characters with the predictions of an established tradition, affect control theory (ACT). Combined, the theories describe core traits of the vil- lain-victim-hero triad and predict audiences’ reactions. Character theory (CT) can help us understand the cultural roots of evaluation, potency, and activity profiles and the robustness of profile ratings. It also provides nuanced information regarding multiplicity in, and sub- types of, characters and how characters work together to define roles. Character types can be strategically deployed in political realms, potentially guiding strategies, goals, and group dynamics. ACT predictions hold up well, but CT suggests several paths for extension and elaboration. In many cases, cultural research and social psychology work on parallel tracks, with little cross-talk. They have much to learn from each other. Keywords affect control theory, character theory, heroes, victims, villains On October 9, 2012, 15-year-old Malala including one attack in December 2014 Yousafzai went to school, despite the Tali- that killed 132 schoolchildren and another ban’s intense campaign to stop female in January 2016 where 22 people were education in her region of Pakistan and gunned down at a university. Why did despite its death threats against her and Malala’s story touch Western audiences, her father. -

Super Heroes

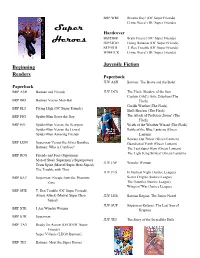

BRP WRE Bizarro Day! (DC Super Friends) Crime Wave! (DC Super Friends) Super Hardcover B8555BR Brain Freeze! (DC Super Friends) Heroes H2934GO Going Bananas (DC Super Friends) S5395TR T. Rex Trouble (DC Super Friends) W9441CR Crime Wave! (DC Super Friends) Juvenile Fiction Beginning Readers Paperback JUV ASH Batman: The Brave and the Bold Paperback BRP ASH Batman and Friends JUV DCS The Flash: Shadow of the Sun Captain Cold’s Artic Eruption (The BRP BRI Batman Versus Man-Bat Flash) Gorilla Warfare (The Flash) BRP ELI Flying High (DC Super Friends) Shell Shocker (The Flash) BRP FIG Spider-Man Saves the Day The Attack of Professor Zoom! (The Flash) BRP HIL Spider-Man Versus the Scorpion Wrath of the Weather Wizard (The Flash) Spider-Man Versus the Lizard Battle of the Blue Lanterns (Green Spider-Man Amazing Friends Lantern) Beware Our Power (Green Lantern) BRP LEM Superman Versus the Silver Banshee Guardian of Earth (Green Lantern) Batman: Who is Clayface? The Last Super Hero (Green Lantern) The Light King Strikes! (Green Lantern) BRP ROS Friends and Foes (Superman) Man of Steel: Superman’s Superpowers JUV JAF Wonder Woman Team Spirit (Marvel Super Hero Squad) The Trouble with Thor JUV JUS In Darkest Night (Justice League) BRP SAZ Superman: Escape from the Phantom Secret Origins (Justice League) Zone The Gauntlet (Justice League) Wings of War (Justice League) BRP SHE T. Rex Trouble (DC Super Friends) Aliens Attack (Marvel Super Hero JUV LER Batman Begins: The Junior Novel Squad) JUV SUP Superman Returns: The Last Son of BRP STE I Am Wonder -

Zoology Courses 1

Zoology Courses 1 Zoology Courses Courses ZOOL 2406. Vertebrate Zoology. Vertebrate Zoology: A survey of basic classification, functional systems, and biology of vertebrates. MATH 1508 may be taken concurrently with ZOOL 2406. Course fee required. [Common Course Number BIOL 1313] Department: Zoology 4 Credit Hours 6 Total Contact Hours 3 Lab Hours 3 Lecture Hours 0 Other Hours Prerequisite(s): (BIOL 1107 w/D or better AND BIOL 1305 w/D or better ) AND (BIOL 1108 w/D or better AND BIOL 1306 w/D or better) ZOOL 2466. Invertebrate Zoology. Invertebrate Zoology: Survey and laboratory exercises concerning the invertebrates with emphasis on phylogeny. Course fee required. [Common Course Number BIOL 1413] Department: Zoology 4 Credit Hours 6 Total Contact Hours 3 Lab Hours 3 Lecture Hours 0 Other Hours Prerequisite(s): (BIOL 1107 w/D or better AND BIOL 1305 w/D or better ) AND (BIOL 1108 w/D or better AND BIOL 1306 w/D or better) ZOOL 3464. Medical Parasitology. Medical Parasitology (3-3) A survey of medically important parasites. Prerequisite: ZOOL 2406, or BIOL 1306 and BIOL 1108. Lab fee required. Replaced ZOOL 3364 and ZOOL 1365. Department: Zoology 4 Credit Hours 6 Total Contact Hours 3 Lab Hours 3 Lecture Hours 0 Other Hours Prerequisite(s): (ZOOL 2406 w/D or better ) OR (BIOL 1108 w/D or better AND BIOL 1306 w/D or better) ZOOL 4181. Vertebrate Physiology Methods. Vertebrate Physiology Methods (0-3) Techniques and instrumentation used in the study of vertebrate function. Prerequisites: CHEM 1306-1106 or CHEM 1408 and (1) BIOL 1306-1108, (2) BIOL 2313-2113, (3) BIOL 3414, or (4) ZOOL 2406. -

9/11 Heroes Run GORUCK Division Rules and Requirements

9/11 Heroes Run GORUCK Division Rules and Requirements The GORUCK division of the Travis Manion Foundation 9/11 Heroes Run requires participants to carry a weighted rucksack or other type weighted backpack. We welcome ruckers of all levels to join us and earn a patch, but to compete for a top finisher medal in the GORUCK division, the rucksack must contain the prescribed additional weight based on body weight: ● For participants weighing 149 lbs or less, a 10-pound weight is required to qualify for the competitive GORUCK division. ● For those weighing 150 lbs or more, a 20-pound weight is required to qualify for the competitive GORUCK division. ● Weighted vests are NOT considered rucks and will NOT qualify for the competitive GORUCK division. ● LEOs and Firefighters in full turnout gear DO qualify for the competitive GORUCK division. ● We will weigh your ruck, but not your body! Your body weight is on the honor system. Packs will be weighed at each event prior to the start. Ruckers will receive a bracelet and a special mark on their running bib showing their ruck has met the standard for medal consideration. Packs must be compliant with the prescribed weight for the duration of the event. Ruck for fun! We enthusiastically welcome ruckers who do not carry the minimum weight requirement to participate in the 9/11 Heroes Run and earn their patch! These participants will skip the weigh-in before the event and will not qualify for medal consideration. Come on out and ruck your yoga block! All participants are required to supply their own packs and weights.