Economic-Geographic Essay with Special Reference to Eastern Seas Discovery, Perception, and Use

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Soils As Indicators of Climatic Changes

Yury G. Chendev1*, Аleksandr N. Petin1, Anthony R. Lupo2 1 Russia, National Research Belgorod State University; 308015, Belgorod, Pobeda St. 85; * Corresponding author e-mail: [email protected] 2 USA; University of Missouri; 302 Anheuser-Busch Natural Resources Building, Columbia, MO 65211-7250; e-mail: [email protected] SOILS AS INDICATORS OF CLIMATIC CHANGES GEOGRAPHY 4 ABSTRACT. A number of examples for the system, which sensitively reacts to changes reaction of chernozems in the center of in natural conditions and, in the first place, the East European Plain and their relation to climate change. Therefore, in scientific to different periodical climatic changes literature in connection with soils, arose are examined. According to unequal-age such concepts as “soil-moment” and “soil- chernozems properties, the transition from memory”, “urgent” and “relict” characteristics the Middle Holocene arid conditions to the of soils, and “sensitivity” and “reflectivity” Late Holocene wet conditions occurred of soil properties [Aleksandrovskii, 1983; at 4000 yr BP. Using data on changes of Gennadiev, 1990; Sokolov and Targul’yan, soil properties, the position of boundary 1976; Sokolov, et al., 1986; and others]. between steppe and forest-steppe and the annual amount of precipitation at In contemporary world geography, there approximately 4000 yr BP were reconstructed. still remains a paucity of information on The change from warm-dry to cool-moist the many-sided interrelations of soils climatic phases, which occurred at the end with the other components of the natural of the XX century as a reflection of intra- environment. This is extremely important age-long climatic cyclic recurrence, led to aspect in light of current global ecological the strengthening of dehumification over problems, studies, and policy decisions, the profile of automorphic chernozems and one of which is the problem of climate to the reduction of its content in the upper change. -

Teacher's Book 3

Reinforcement, Extension and Assessment 1 CONTENT AND RESOURCES PHYSICAL GEOGRAPHY CONTENTS FIND OUT ABOUT • The formation of relief • Continental and oceanic relief • The relief and water of the continents • The climates and landscapes of the Earth • Spain: relief, water, climates and landscapes KNOW HOW TO • Understand relief formation: internal and external processes • Distinguish continental and oceanic relief • Identify the main relief features, rivers and lakes of the Earth and Spain • Identify the five main climate zones in the Earth • Identify the main climates and landscapes of each climate zone and Spain • Compare climates and landscapes • Interpret maps of relief, rivers and lakes, and climates of the Earth and Spain • Distinguish continental and marine water • Interpret charts, pie charts, diagrams and climographs • Analyse photos of landscapes • Organise and classify information in tables • Use maps to link geographical features to each other • Analyse the effects of marine currents • Analyse the effects of cyclones BE ABLE TO • Use an atlas • Find the main physical features, rivers and lakes of each continent in a map • Find the main physical features, watersheds and rivers of Spain in a map • Locate the different climates of the continents in a map • Locate the different climates of Spain in a map • Understand the importance of water in human life • Recognise the importance of properly managing fresh water resources • Reflect on the influence of climate on the distribution of world population RESOURCES Reinforcement and extension Digital resources • Relief: formation and features • Libromedia. Physical geography • Water and climates of the Earth • Relief, water and climates of Spain Audio • The seven summits • Track 1: pp. -

Haplotype Frequencies at the DRD2 Locus in Populations of the East European Plain

BMC Genetics BioMed Central Research article Open Access Haplotype frequencies at the DRD2 locus in populations of the East European Plain Olga V Flegontova*1, Andrey V Khrunin1, OlgaILylova1, Larisa A Tarskaia1, Victor A Spitsyn2, Alexey I Mikulich3 and Svetlana A Limborska1 Address: 1Department of Human Molecular Genetics, Institute of Molecular Genetics, Russian Academy of Sciences, Moscow, Russia, 2Medical and Genetics Scientific Centre, Russian Academy of Medical Sciences, Moscow, Russia and 3Institute of Arts, Ethnography and Folklore, National Academy of Sciences of Belarus, Minsk, Belarus Email: Olga V Flegontova* - [email protected]; Andrey V Khrunin - [email protected]; Olga I Lylova - [email protected]; Larisa A Tarskaia - [email protected]; Victor A Spitsyn - [email protected]; Alexey I Mikulich - [email protected]; Svetlana A Limborska - [email protected] * Corresponding author Published: 30 September 2009 Received: 9 March 2009 Accepted: 30 September 2009 BMC Genetics 2009, 10:62 doi:10.1186/1471-2156-10-62 This article is available from: http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2156/10/62 © 2009 Flegontova et al; licensee BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Abstract Background: It was demonstrated previously that the three-locus RFLP haplotype, TaqI B-TaqI D-TaqI A (B-D-A), at the DRD2 locus constitutes a powerful genetic marker and probably reflects the most ancient dispersal of anatomically modern humans. Results: We investigated TaqI B, BclI, MboI, TaqI D, and TaqI A RFLPs in 17 contemporary populations of the East European Plain and Siberia. -

England's Search for the Northern Passages in the Sixteenth And

- ARCTIC VOL. 37, NO. 4 (DECEMBER 1984) P. 453472 England’s Search for the Northern Passages in the Sixteenth and. Early Seventeenth Centuries HELEN WALLIS* For persistence of effort in the. face of adversity no enterprise this waie .is of so grete.avantage over the other navigations in in thehistory of exploration wasmore remarkable than shorting of half the waie, for the other must.saileby grete cir- England’s search for the northern passages to the Far East. .cuites and compasses and .thes shal saile by streit wais and The inspiration for the search was the hope of sharing in the lines” (Taylor, 1932:182). The dangerous part of the.naviga- riches of oriental commerce. In the tropical.regions of the Far tion was reckoned.to .be the last 300 leagues .before reaching East were situated, Roger Barlow wrote in 1541, “the most the Pole and 300 leagues beyond it (Taylor, 1932:181). Once richest londes and ilondes in the the worlde, for all the golde, over the Polethe expedition would choose whetherto sail east- spices, aromatikes and pretiose stones” (Barlow, 1541: ward to the Orient by way of Tartary or westward “on the f”107-8; Taylor, 1932:182). England’s choice of route was backside ofall the new faund land” [NorthAmerica]. limited, however, by the prior discoveries of .Spain and Por- Thorne’s confident .opinion that“there is no lande inhabitable tugal, who by the Treatyof Tordesillas in 1494 had divided the [i.e. uninhabitable€, nor Sea innavigable” (in Hakluyt, 1582: world between them. With the “waie ofthe orient” and ‘The sig.DP) was a maxim (as Professor.Walter Raleigh (19O5:22) waie of the occydent” barred, it seemed that Providence had commented) “fit to be inscribed as a head-line on the charter especially reserved for England. -

UKRAINE in EUROPE (Geographical Location and Geopolitical Situation)

UKRAINE IN EUROPE (Geographical location and geopolitical situation) Geographical setting Ukraine is predominantly located in the south- The Ukrainian state is located on the ern part of eastern Europe between 44 and 52º of interface of large physica-geographical units, northern latitude and 22 and 40º of eastern longi- such as the East European Plain and the Eurasian tude (Figure 1). Its territory spans 1,316 km from Mountain Range (partly comprised of the the west to the east and 893 km from the north to Carpathians and partly the Crimean Mountains). the south. Geographical extremes are the town Plains constitute the overwhelming majority of of Chop (Transcarpathia) in the west and the Ukraine's territory (95%). With the exception of village of Chervona Zirka (Luhans’k oblast) in the aforementioned mountains, the topography the east; the village of Hremiach (Chernihiv ob- provides adequate opportunity for agriculture, last) in the north and the headland of Sarich in industry and residential housing, as well as for Crimea in the south. From the south the coasts the development of infrastructure, including the are lapped by the waters of the Black Sea and transport network. There are a variety of natural the Sea of Azov. zones within the portion of the East European 9 Plain that falls within Ukrainian territory, name- logical and climatic conditions, the characteris- ly, mixed forests, broad-leaved forests, forest tics of water regime and soil cover, as well as the steppe and steppe. They differ in geomorpho- internal structure of landscape complexes. State territory A largely independent state named Ukraine ceived 92,568 km² from the previous territory first appeared on the map of Europe in 1918 of Poland and 25,832 km² from Romania. -

AAR Chapter 2

Go back to opening screen 9 Chapter 2 Physical/Geographical Characteristics of the Arctic –––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––– Contents 2.2.1. Climate boundaries 2.1. Introduction . 9 On the basis of temperature, the Arctic is defined as the area 2.2. Definitions of the Arctic region . 9 2.2.1. Climate boundaries . 9 north of the 10°C July isotherm, i.e., north of the region 2.2.2. Vegetation boundaries . 9 which has a mean July temperature of 10°C (Figure 2·1) 2.2.3. Marine boundary . 10 (Linell and Tedrow 1981, Stonehouse 1989, Woo and Gre- 2.2.4. Geographical coverage of the AMAP assessment . 10 gor 1992). This isotherm encloses the Arctic Ocean, Green- 2.3. Climate and meteorology . 10 2.3.1. Climate . 10 land, Svalbard, most of Iceland and the northern coasts and 2.3.2. Atmospheric circulation . 11 islands of Russia, Canada and Alaska (Stonehouse 1989, 2.3.3. Meteorological conditions . 11 European Climate Support Network and National Meteoro- 2.3.3.1. Air temperature . 11 2.3.3.2. Ocean temperature . 12 logical Services 1995). In the Atlantic Ocean west of Nor- 2.3.3.3. Precipitation . 12 way, the heat transport of the North Atlantic Current (Gulf 2.3.3.4. Cloud cover . 13 Stream extension) deflects this isotherm northward so that 2.3.3.5. Fog . 13 2.3.3.6. Wind . 13 only the northernmost parts of Scandinavia are included. 2.4. Physical/geographical description of the terrestrial Arctic 13 Cold water and air from the Arctic Ocean Basin in turn 2.4.1. -

Ralph Fitch, England's Pioneer to India and Burma

tn^ W> a-. RALPH FITCH QUEEN ELIZABETH AND HER COUNSELLORS RALPH FITCH flMoneet; to Snfcta anD 3Burma HIS COMPANIONS AND CONTEMPORARIES WITH HIS REMARKABLE NARRATIVE TOLD IN HIS OWN WORDS + -i- BY J. HORTON RYLEY Member of the Hnkhiyt Society LONDON T. FISHER UNWIN PATERNOSTER SQUARE 1899 reserved.'} PREFACE much has been written of recent years of the SOhistory of what is generally known as the East India Company, and so much interesting matter has of late been brought to light from its earliest records, that it seems strange that the first successful English expedition to discover the Indian trade should have been, comparatively speaking, overlooked. Before the first East India Company was formed the Levant Com- pany lived and flourished, largely through the efforts of two London citizens. Sir Edward Osborne, sometime Lord Mayor, and Master Richard Staper, merchant. To these men and their colleagues we owe the incep- tion of our great Eastern enterprise. To the fact that among them there were those who were daring enough, and intelligent enough, to carry their extra- ordinary programme into effect we owe our appear- ance as competitors in the Indian seas almost simultaneously with the Dutch. The beginning of our trade with the East Indies is generally dated from the first voyage of James Lancaster, who sailed from Plymouth in 1591. But, great as his achievement was, , **** 513241 vi PREFACE and immediately pregnant with consequences of a permanent character, he was not the first Englishman to reach India, nor even the first to return with a valuable store of commercial information. -

Unit V: Europe Physical: Europe Is Sometimes Described As A

Unit V: Europe Physical: Europe is sometimes described as a peninsula of peninsulas. A peninsula is a piece of land surrounded by water on three sides. Europe is a peninsula of the Eurasian supercontinent and is bordered by the Arctic Ocean to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the west, and the Mediterranean, Black, and Caspian Seas to the south. Europes main peninsulas are the Iberian, Italian, and Balkan, located in southern Europe, and the Scandinavian and Jutland, located in northern Europe. The link between these peninsulas has made Europe a dominant economic, social, and cultural force throughout recorded history. Europe can be divided into four major physical regions, running from north to south: Western Uplands, North European Plain, Central Uplands, and Alpine Mountains. Western Uplands The Western Uplands, also known as the Northern Highlands, curve up the western edge of Europe and define the physical landscape of Scandinavia (Norway, Sweden, and Denmark), Finland, Iceland, Scotland, Ireland, the Brittany region of France, Spain, and Portugal. The Western Uplands is defined by hard, ancient rock that was shaped by glaciation. Glaciation is the process of land being transformed by glaciers or ice sheets. As glaciers receded from the area, they left a number of distinct physical features, including abundant marshlands, lakes, and fjords. A fjord is a long and narrow inlet of the sea that is surrounded by high, rugged cliffs. Many of Europes fjords are located in Iceland and Scandinavia. North European Plain The North European Plain extends from the southern United Kingdom east to Russia. It includes parts of France, Belgium, the Netherlands, Germany, Denmark, Poland, the Baltic states (Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania), and Belarus. -

St. Lawrence High School

ST. LAWRENCE HIGH SCHOOL TOPIC- EUROPE Sub: Geography Class: 7 F. M. 15 WORKSHEET NO. 10 Date: 24.4.2020 OBJECTIVE QUESTIONS Choose the correct option: 1x15=15 1) Europe is bordered in the south by the - a) Barents Sea b) Mediterranean Sea c) North Sea 2) The Northern Highlands of Europe extends from the Ural Mountains to the - a) Atlantic Ocean b) Pacific Ocean c) Arctic Ocean 3) The northern part of the Northern Highlands is called the - a) Ardennes b) Sudetenland c) Fennoscandia 4) The Urals extend from the Pay-Khoy ridge in the north to the - a) Aral Sea in the south b) Adriatic Sea in the south c) Aegean Sea in the south 5) The Scandinavian Mountains extend across the countries of Sweden, Norway and - a) Iceland b) Poland c) Finland 6) The North European Plain extends from the shores of the Atlantic Ocean to the - a) Voldai Mountains b) Ural Mountains c) Caucasus Mountains 7) The long narrow strips of sea between high cliffs are called the - a) fjords b) gulfs c) straits 8) The Beinn Eighe is a group of - a) mountains b) plateaus c) islands 9) The westward extension of the North European plains is the - a) Swan Isles b) British Isles c) Falkland Isles 10) The North European Plains is broadest in the - a) western part b) northern part c) eastern part 11) The East European Plain implies the - a) Hungarian plain b) Russian plain c) Andalusian plain 12) The Scandinavian shield is made up of - a) Igneous & Metamorphic rocks b) Igneous & Sedimentary rocks c) Sedimentary & Metamorphic rocks 13) To the south of the North European Plains lies the - a) Northwestern Highlands b) Alpine Highlands c) Eastern Highlands 14) The plains of Lombardy lies in - a) Hungary b) Spain c) Italy 15) The Scandinavian Shield is also known as the - a) Baltic Shield b) Adriatic Shield c) White Shield Sanjukta Chakraborty. -

TEKS Clarification

TEKS Clarification Social Studies Grade 6 2014 - 2015 page 1 of 1 Print Date 08/14/2014 Printed By Joe Nicks, KAUFMAN ISD TEKS Clarification Social Studies Grade 6 2014 - 2015 GRADE 6 §113.17. Implementation of Texas Essential Knowledge and Skills for Social Studies, Middle School, Beginning with School Year 20112012. The provisions of §§113.18113.20 of this subchapter shall be implemented by school districts beginning with the 20112012 school year. Source: The provisions of this §113.17 adopted to be effective August 23, 2010, 35 TexReg 7232; amended to be effective October 17, 2011, 36 TexReg 6946. §113.18. Social Studies, Grade 6, Beginning with School Year 20112012. 6.Intro.1 In Grade 6, students study people, places, and societies of the contemporary world. Societies for study are from the following regions of the world: Europe, Russia and the Eurasian republics, North America, Central America and the Caribbean, South America, Southwest Asia-North Africa, Sub- Saharan Africa, South Asia, East Asia, Southeast Asia, Australia, and the Pacific realm. Students describe the influence of individuals and groups on historical and contemporary events in those societies and identify the locations and geographic characteristics of various societies. Students identify different ways of organizing economic and governmental systems. The concepts of limited and unlimited government are introduced, and students describe the nature of citizenship in various societies. Students compare institutions common to all societies such as government, education, and religious institutions. Students explain how the level of technology affects the development of the various societies and identify different points of view about events. -

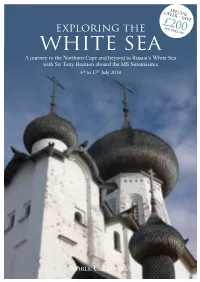

WHITE SEA a Journey to the Northern Cape and Beyond to Russia’S White Sea with Sir Tony Brenton Aboard the MS Serenissima 3Rd to 17Th July 2018 Solovetsky Monastery

SPECIAL OFFER - SAVE £200 EXPLORING THE PER PERSON WHITE SEA A journey to the Northern Cape and beyond to Russia’s White Sea with Sir Tony Brenton aboard the MS Serenissima 3rd to 17th July 2018 Solovetsky Monastery or decades the White Sea was a forbidden area the North Cape as The North Cape Fand today because of its geographic isolation it well as Murmansk, Hammerfest Tromso remains a region of great mystery. During this voyage the largest city north Finmark Vardo Murmansk we will have six days in the region where we will of the Arctic Circle NORWAY WHITE concentrate on Archangel and the Solovetsky Islands. in the world. Here SEA It was on the Solovetsky Islands that Stalin built one we will visit the Solovetsky Archangel Islands of his infamous Gulags, the ‘Red Army’ established cemetery of the RUSSIA a vital submarine base and an important shipbuilding officers and industry was founded. soldiers of the Allied Forces who bravely manned the convoys during World War II. To add to your The most fascinating aspect of the Solovetsky islands experience, you will be joined on board by an expert is the 16th century Solovetsky Monastery. This vast team including naturalists who through onboard Medieval fortress with its fascinating and turbulent briefings and lectures will add to your understanding history is remarkably well preserved. It is believed of the geology, flora and fauna of the region. that Vikings, both English and Norman came to the White Sea to fish and trade for furs up until the 13th century when global cooling made navigation Guest Speaker – Sir Tony Brenton difficult. -

Suspended Sediment Yield Mapping of Northern Eurasia

326 Sediment Dynamics from the Summit to the Sea (Proceedings of a symposium held in New Orleans, Louisiana, USA, 11–14 December 2014) (IAHS Publ. 367, 2014). Suspended sediment yield mapping of Northern Eurasia K.A. MALTSEV, O.P. YERMOLAEV & V.V. MOZZHERIN Kazan Federal University, Department of the Landscape Ecology, Institute of Ecology and Geography, 18 Kremlevskay St, Kazan, Russia, 420008 Kazan, Russia [email protected] Abstract The mapping of river sediment yields at continental or global scale involves a number of technical difficulties that have largely been ignored. The maps need to show the large zonal peculiarities of river sediment yields, as well as the level (smoothed) local anomalies. This study was carried out to create a map of river sediment yields for Northern Eurasia (within the boundaries of the former Soviet Union, 22 × 106 km2) at a scale of 1:1 500 000. The data for preparing the map were taken from the long-term observations recorded at more than 1000 hydrological stations. The data have mostly been collected during the 20th century by applying a single method. The creation of this map from the study of river sediment yield is a major step towards enhancing international research on understanding the mechanical denudation of land due mainly to erosion. Key words suspended sediment yield; GIS; thematic map; watershed boundaries; Northern Eurasia INTRODUCTION The mapping of river suspended sediment yield is the most significant challenge for the experts working in the fields of hydrology and geomorphology. This challenge can be attributed mainly to the sparse network of hydrological stations that systematically observe sediment yield.