Reconstructing the History of Ocean Life Around Ascension Island

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

April 17, 2017 2017 State Solo & Ensemble South Festival Schedule Dear Colleagues, How Wonderful to Work in an Area Where Th

April 17, 2017 2017 State Solo & Ensemble South Festival Schedule Dear colleagues, How wonderful to work in an area where there are so many talented music students! It is a credit to you that so many students attend this festival. It is your efforts, combined with that of the students (and in many cases, the private studio teachers), which produces such a packed schedule! At this point, no official changes to the schedule will be made. If there are emergencies, most adjudicators will be in the rooms by 8:30am and you may ask the adjudicators to allow you to perform before normal festival time begins. If necessary, you may also switch with another entry from within your school or another school. Track Meet at Orem High Orem High School will be hosting both the South State Solo & Ensemble Festival and the State Track Tiger Trials Meet. Because of this Bus parking will be particularly difficult. The Alpine District has requested that buses drop-off at the OHS Main Entrance and that they park at Scera Park Elementary Parking Lot to south of Orem High. Parking instructions are included on the map. Festival Operation Take a moment to familiarize yourself with the map of Orem High School. There will be information tables with schedules and maps throughout the buildings. The auxiliary gym will be available as a warm-up room equipped with a few electronic pianos. This room will open at 8:00am—since the majority of the festival doesn’t begin until 9:00am, this should leave the early entries plenty of time to warm-up. -

NEUEEUE EITUNG WWERRAERRA-Z-ZEITUNG Amtsblatt Der Gemeinde Gerstungen Gerstungen Mit Untersuhl * Lauchröden * Oberellen * Unterellen * Neustädt * Sallmannshausen

NNEUEEUE WWERRAERRA-Z-ZEITUNGEITUNG Amtsblatt der Gemeinde Gerstungen Gerstungen mit Untersuhl * Lauchröden * Oberellen * Unterellen * Neustädt * Sallmannshausen Jahrgang 18 Freitag, den 21. Mai 2010 Nummer 10 Ausgabe: 10/2010 Amtsblatt „Neue Werra-Zeitung“ Seite 2 Rufnummern und Öffnungszeiten Gemeindeverwaltung Gerstungen Burgmuseum Brandenburg Wilhelmstraße 53 Rufnummer ...................................036927/91735 oder 90619 99834 Gerstungen E-Mail: ...........................................info@die-brandenburg.de Tel.: ................................................................................245-0 Öffnungszeiten: Fax: .............................................................................245-50 April - September Sprechzeiten im Rathaus: Mittwoch und Freitag ..................................10:00 - 16:00 Uhr Montag: ..............................................................geschlossen Sonn-und Feiertage ...................................11:00 - 17:00 Uhr Dienstag: ..........................09.00 - 12.00 u. 14.00 - 18.00 Uhr Mittwoch: ............................................................geschlossen Wichtige Rufnummern und Öffnungszeiten Donnerstag: ......................09.00 - 12.00 u. 14.00 - 15.30 Uhr Freitag: .......................................................09.00 - 12.00 Uhr Polizei Notruf ....................................................................110 Sprechzeit des Bürgermeisters: Polizei-Sprechstunde in Gerstungen nur nach vorheriger telefonischer Vereinbarung KOBB Herr Schmidt, zu den -

Proper 23. October 11. 2020

Welcome to The Church of St. Paul in the Desert The Nineteenth Sunday after Pentecost Proper 23 Sunday, October 11, 2020, 10:30 am Our Mission Statements God has invited us to share the abundant life of Jesus Christ through the Church of St. Paul in the Desert by serving Christ in others and by gathering to praise and thank God in worship. We are a welcoming, empowering, supportive community. The Episcopal Diocese of San Diego is a missionary community that dares to follow Jesus Christ in his life of fearless love for the world. 125 West El Alameda, Palm Springs, CA 92262 ● 760.320.7488 ● www.stpaulsps.org 1 The Holy Eucharist: Rite Two Prelude Pastorale, from Book II —Louis Vierne Welcome & Announcements The Word of God The Entrance Hymn #7 Christ whose glory fills the skies The people standing, the Celebrant says The Rev. Lorenzo Lebrija Blessed be God: Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. People Blessed be God’s kingdom, now and for ever. Amen. The Celebrant may say Almighty God, to you all hearts are open, all desires known, and from you no secrets are hid: Cleanse the thoughts of our hearts by the inspiration of your Holy Spirit, that we may perfectly love you, and worthily magnify your holy Name; through Christ our Lord. Amen. 2 The Hymn of Praise: Glory to God Gloria in excelsis 3 The Collect of the Day The Celebrant says to the people The Lord be with you. And also with you. Let us pray. The Celebrant says the Collect. Lord, we pray that your grace may always precede and follow us, that we may continually be given to good works; through Jesus Christ our Lord, who lives and reigns with you and the Holy Spirit, one God, now and for ever. -

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist Ein Karaokesystem der Firma Showtronic Solutions AG in Zusammenarbeit mit Karafun. Karaoke-Katalog Update vom: 13/10/2020 Singen Sie online auf www.karafun.de Gesamter Katalog TOP 50 Shallow - A Star is Born Take Me Home, Country Roads - John Denver Skandal im Sperrbezirk - Spider Murphy Gang Griechischer Wein - Udo Jürgens Verdammt, Ich Lieb' Dich - Matthias Reim Dancing Queen - ABBA Dance Monkey - Tones and I Breaking Free - High School Musical In The Ghetto - Elvis Presley Angels - Robbie Williams Hulapalu - Andreas Gabalier Someone Like You - Adele 99 Luftballons - Nena Tage wie diese - Die Toten Hosen Ring of Fire - Johnny Cash Lemon Tree - Fool's Garden Ohne Dich (schlaf' ich heut' nacht nicht ein) - You Are the Reason - Calum Scott Perfect - Ed Sheeran Münchener Freiheit Stand by Me - Ben E. King Im Wagen Vor Mir - Henry Valentino And Uschi Let It Go - Idina Menzel Can You Feel The Love Tonight - The Lion King Atemlos durch die Nacht - Helene Fischer Roller - Apache 207 Someone You Loved - Lewis Capaldi I Want It That Way - Backstreet Boys Über Sieben Brücken Musst Du Gehn - Peter Maffay Summer Of '69 - Bryan Adams Cordula grün - Die Draufgänger Tequila - The Champs ...Baby One More Time - Britney Spears All of Me - John Legend Barbie Girl - Aqua Chasing Cars - Snow Patrol My Way - Frank Sinatra Hallelujah - Alexandra Burke Aber Bitte Mit Sahne - Udo Jürgens Bohemian Rhapsody - Queen Wannabe - Spice Girls Schrei nach Liebe - Die Ärzte Can't Help Falling In Love - Elvis Presley Country Roads - Hermes House Band Westerland - Die Ärzte Warum hast du nicht nein gesagt - Roland Kaiser Ich war noch niemals in New York - Ich War Noch Marmor, Stein Und Eisen Bricht - Drafi Deutscher Zombie - The Cranberries Niemals In New York Ich wollte nie erwachsen sein (Nessajas Lied) - Don't Stop Believing - Journey EXPLICIT Kann Texte enthalten, die nicht für Kinder und Jugendliche geeignet sind. -

Special-Commencement.Pdf

STUDENT LIFE | THE FINISH LINE 1 CONGRATULATIONS CLASS OF 2011 STUDENT LIFE THE FINISH LINE CONTENTS SECTIONS FEATURES 02 NEWS 18 SCENE 11 5 TO RECEIVE HONORARY DEGREES Overviews of each year, honorary degree Places to go during graduation weekend. Find out about who is receiving an honorary degree. recipients, speakers of 2010-2011. 22 CADENZA 19 NO RESERVATION? NO PROBLEM 12 FORUM The Cadenza staff reflects on the past. Forgot to reserve a table for that big family dinner? Student Life seniors share final words of Scene can help you out. advice. 26 SPORTS Coaches say good-bye to their senior players. 22 A REVIEW OF FALL 2007 Everything you watched your freshman year. 2 6 19 22 26 Editor in Chief: Michelle Merlin Online Editor: David Seigle Associate Editor: Alex Dropkin Desigh Chief: Mary Yang Managing Editor: Hannah Lustman Copy Chief: Lauren Cohn Cover page photo by: Matt Mitgang Senior News Editor: Chloe Rosenberg Copy Editors: Michelle Aranovsky, Sarah Cohen, Stephen Senior Forum Editor: Daniel Deibler Hayes, Rebecca Horowitz, Robyn Husa, Lauren Keblusek, Inside photo by: Senior Sports Editors: Sahil Patel, Kurt Rohrbeck Maia Lamdany, Nora Long, Marty Nachman, Rachel Noccioli, Student Life Archives Senior Senior Editor: Davis Sargeant Lauren Nolte, Courtney Safir, Jordan Weiner Senior Cadenza Editor: Andie Hutner General Manager: Andrew O’Dell Senior Photo Editor: Matt Mitgang Advertising Manager: Sara Judd Copyright 2011 Washington University Student Media, Inc. (WUSMI). Student Life is a financially and editorially independent, student-run newspaper serving the Washington University community. Our newspaper is a publication of -WUSMI and does not necessarily represent the views of the Washington University administration. -

Karaoke-Katalog Update Vom: 17/06/2020 Singen Sie Online Auf Gesamter Katalog

Karaoke-Katalog Update vom: 17/06/2020 Singen Sie online auf www.karafun.de Gesamter Katalog TOP 50 Shallow - A Star is Born Take Me Home, Country Roads - John Denver Cordula grün - Die Draufgänger Dance Monkey - Tones and I Rote Lippen soll man küssen - Gus Backus Amoi seg' ma uns wieder - Andreas Gabalier Perfect - Ed Sheeran Tears In Heaven - Eric Clapton Chasing Cars - Snow Patrol Griechischer Wein - Udo Jürgens My Way - Frank Sinatra You Are the Reason - Calum Scott Someone You Loved - Lewis Capaldi Lemon Tree - Fool's Garden Tage wie diese - Die Toten Hosen Angels - Robbie Williams 99 Luftballons - Nena Up Where We Belong - Joe Cocker Im Wagen Vor Mir - Henry Valentino And Uschi I Want It That Way - Backstreet Boys Zombie - The Cranberries All of Me - John Legend Ich war noch niemals in New York - Ich War Noch New York, New York - Frank Sinatra Blinding Lights - The Weeknd Niemals In New York Hulapalu - Andreas Gabalier Hallelujah - Alexandra Burke Creep - Radiohead EXPLICIT Verdammt, Ich Lieb' Dich - Matthias Reim Can't Help Falling In Love - Elvis Presley Let It Be - The Beatles Always Remember Us This Way - A Star is Born Atemlos durch die Nacht - Helene Fischer A Million Dreams - The Greatest Showman Kuliko Jana, Eine neue Zeit - Oonagh Eine Nacht - Ramon Roselly In The Ghetto - Elvis Presley (Everything I Do) I Do It For You - Bryan Adams Can You Feel The Love Tonight - The Lion King Bohemian Rhapsody - Queen Egal - Michael Wendler Warum hast du nicht nein gesagt - Roland Kaiser Der hellste Stern (Böhmischer Traum) - DJ Ötzi Ich wollte nie erwachsen sein (Nessajas Lied) - Über Sieben Brücken Musst Du Gehn - Peter Maffay Uber den Wolken - Reinhard Mey Losing My Religion - R.E.M. -

Where It Began

SCHLAGERBOOOM 2018 1 KLUBBB3- Openingmedley Florian Silbereisen: 5, 4, 3, 2 Eins kann mir keiner Eins kann mir keiner Eins kann mir keiner nehmen Und das ist die pure Lust am Leben Eins kann mir keiner Eins kann mir keiner Eins kann mir keiner nehmen Und das ist die pure Lust am Leben Hey Hey Hey Hey Hey Hey Hey Hey Hey Hey Hey Hey Hey Hey Hey Hey Eins kann mir keiner Eins kann mir keiner Eins kann mir keiner Eins kann mir keiner Eins kann mir keiner nehmen Und das ist die pure Lust am Leben Eins kann mir keiner Eins kann mir keiner Eins kann mir keiner Eins kann mir keiner SCHLAGERBOOOM 2018 2 KLUBBB3- Openingmedley Eins kann mir keiner nehmen Und das ist die pure Lust am Leben Eins kann mir keiner SCHLAGERBOOOM 2018 3 KLUBBB3- Openingmedley Klubbb3: Griechischer Wein ist so wie das Blut der Erde Komm', schenk dir ein Und wenn ich dann traurig werde Liegt es daran Dass ich immer träume von daheim Du musst verzeih'n Griechischer Wein und die altvertrauten Lieder Schenk' noch mal ein Denn ich fühl' die Sehnsucht wieder In dieser Stadt Werd' ich immer nur ein Fremder sein Und allein SCHLAGERBOOOM 2018 4 KLUBBB3- Openingmedley Nein Sorg' dich nicht um mich Du weißt Ich liebe das Leben Und weine ich manchmal noch um dich Das geht vorüber sicherlich SCHLAGERBOOOM 2018 5 KLUBBB3- Openingmedley Nanananana Hey, hey, hey, hey Nanananana Life Nanananana Life is life Nanananana Hey, hey, hey, hey Life Nanananana Life is life Nanananana When we all give the power We all give the best Every minute of an hour Don't think about the rest And you all get -

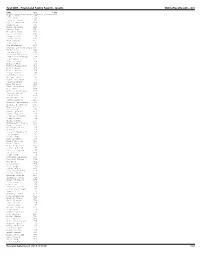

Unclaimed Funds Status Report Unclaimed County Warrants $0.00 - $1,000,000.00

Unclaimed Funds Status Report Unclaimed County Warrants $0.00 - $1,000,000.00 Claim ID Case No Description Name Amount STATUS: DOWNLOAD W-JE700102-1-11687927 C/O JUSTIN $6.00 W-JE600052-1-11582251 GENE TALLEY $40.97 W-JE900053-1-11792664 937 PROPERTIES $348.50 W-JE900053-1-11784184 A & A CAR COMPANY $500.00 W-JE700102-1-11697935 A LOVING HEART YOUTH $154.00 SERVICES INC W-JE600052-1-11571360 A. CELESTE GROOMS $6.00 W-JE600052-1-11580034 A. CELESTE GROOMS $6.00 W-JE600052-1-11571359 A. CELESTE GROOMS $6.00 W-JE900053-1-11839854 A.B. (MINOR) $6.00 W-JE900053-1-11823215 A.S. (MINOR) $6.00 W-JE500064-1-11518632 AARIKA ROBINSON $6.00 W-JE700102-1-11707418 AARON BLIZZARD $6.00 1 2/18/2020 9:31:49AM Unclaimed Funds Status Report Unclaimed County Warrants $0.00 - $1,000,000.00 Claim ID Case No Description Name Amount W-JE000055-1-11883799 AARON COEY $6.00 W-JE700102-1-11693751 AARON COMBS $6.00 W-JE000055-1-11858088 AARON CORNWELL $6.00 W-JE000055-1-11873669 AARON CORNWELL $6.00 W-JE500064-1-11521280 AARON DURRANI $10.00 W-JE600052-1-11624743 AARON GUILFOIL $6.00 W-JE600052-1-11568593 AARON GUNTER $10.00 W-JE600052-1-11563630 AARON HALE $10.00 W-JE000055-1-11873015 AARON HENDERSON $6.00 W-JE900053-1-11825123 AARON ISIAH HALL $200.00 W-JE000055-1-11850201 AARON K ZACHARY SR $10.00 W-JE500064-1-11548005 AARON KEMP $6.00 2 2/18/2020 9:31:49AM Unclaimed Funds Status Report Unclaimed County Warrants $0.00 - $1,000,000.00 Claim ID Case No Description Name Amount W-JE000055-1-11885373 AARON KIM $10.00 W-JE000055-1-11864303 AARON M. -

Docketed 26 Sep 2 3 2013 27 28 1 Certificate of Service

1 BEFORE THE ARIZONA COMMISSlON 2 3 Bob Stump, Chairman 2013 SEP 23 A If: 30 Gary Pierce, Commissioner 4 Brenda Burns, Commissioner . :CiXP CQMMISS.;: Bob Burns, Commissioner XXKET CONTR~L 5 Susan Bitter Smith, Commissioner 6 7 IN THE MATTER OF THE APPLICATION OF ARIZONA PUBLIC SERVICE Docket No. E-01345A-13-0248 8 COMPANY FOR APPROVAL OF NET METERING COST SHIFT SOLUTION. 9 10 NOTICE OF FILING DOCUMENTS OF INTEREST 11 The Alliance for Solar Choice (“TASC”), through undersigned counsel, respectfully 12 13 submits the attached petition to maintain net metering signed by 19,559 Arizona residents as 14 described in the cover letter completed by Anne Smart, Executive Director, The Alliance for 15 Solar Choice. 16 RESPECTFULLY SUBMITTED this 23rd day of September, 2013. / 17 18 Hugh Hallman 19 E. Hallman & Afiliates, P.C. 20 201 1 North Campo Alegre Road Suite 100 21 Tempe, AZ 85281 480-424-3 900 22 BarNo. 12164 23 Attorney for The Alliance for Solar Choice 24 Arizona Corporation Commission 25 DOCKETED 26 SEP 2 3 2013 27 28 1 CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE 2 I hereby certify I have this day sent via hand delivery an original and thirteen copies of the 3 foregoing NOTICE OF FILING OF DOCUMENTS OF INTEREST BY THE ALLIANCE FOR SOLAR CHOICE on this 23rd day of September, 2013 with: 4 Docket Control 5 Arizona Corporation Commission 6 1200 W. Washington Street Phoenix, Arizona 85007 7 I hereby certify that I have this day served the foregoing documents via regular mail on all parties 8 of record and all persons listed on the official service list for Docket No. -

Mit Swing in Eine Neue Blamage?

Seite 6ABCDE ·Nummer 113 AUSALLER WELT Samstag, 16.Mai 2009 LEUTE KURZ NOTIERT MitSwing in eine neue Blamage? New York schließt wegen Grippe Schulen Heute Abend startet Deutschland mit „Miss Kiss Kiss Bang“ beim Eurovision Song Contest in Moskau NewYork. Nach einem ersten fast tödlich verlaufenen Fall als Außenseiter.Ein Jahr nachdem Debakel der No Angels ist die Verunsicherung so groß wie nie. von Schweinegrippe in New York hat die Stadt drei Schu- VONRALF ISERMANN zent international bewiesen, dass len geschlossen. Ein stellver- ̈ Loki Schmidt (90), Ehefrau von er ein Händchen für Hits hat. Mit tretender Rektor aus dem Altbundeskanzler Helmut München. Kann die am Boden lie- der Techno-Hymne „Das Boot“ Stadtteil Queens war nach ei- Schmidt,hat am Freitag das nach gende deutsche Fan-Gemeinde des war er 1992 in 22 Ländern auf ner Infektion mit dem Virus ihr benannte Tropen-Gewächs- Eurovision Song Contest (ESC) Platz 1 der Charts. Christensen schwer erkrankt und überlebte haus im Botanischen Garten in strahlend auferstehen? Oder wird produzierte die Bands Bro'Sis und nur mit Hilfe künstlicher Beat- Rostockeröffnet.„Ichdanke, dass sie in Europa erneut bis auf die Right Said Fred, schaffte mit dem mung, wie das „Wall Street ichdurch Ihreehrenvolle Na- Knochen blamiert? Selten war die frechen „Du hast den schönsten Journal“ am Freitag berichtete. mensgebung immer ein bisschen Verunsicherung so groß wie vor Arsch der Welt“ vor zwei Jahren in Bürgermeister Michael Bloom- dabei sein darf“, sagte die 90- dem diesjährigen Wettbewerb. Deutschland einen Nummer-1-Hit berg ordnete daraufhin die Jährige. Als Geschenk überreichte Zwei Jahre nach dem enttäuschen- und mischte auch bei „Deutsch- Schließung der betroffenen sie exotische Pflanzen, vondenen den 19. -

Friend and Family Search - Results Onlineraceresults.Com

Test 2005 - Friend and Family Search - results OnlineRaceResults.com NAME DIV TIME ---------------------- ------- ----------- Sophie Walker F70 Jill Kohla F46 Diana Bruckner F70 Justin Laughlin M38 Ruifang Li F43 Micah Sterling M26 Gianna Terra F9 Meredith Linde F25 Carter Wilson M9 Karen Vicsik F35 Darin Parks M42 mike webster M37 Jiyu Kim F8 Jed MacArthur M38 Stryder Lafone-Demaroi M8 Ed McDevitt M40 Don McJunkin M68 Kristina Wilcoxson F23 Debbie Eichelberger F35 Jay Tippets M35 Jennifer Hart F39 Angela Upton F31 Autumn Warrington F37 Ashley Henkle F36 Nicole Martin F29 Tracy Hansen F61 Samantha Lucero F44 Whitney Shaw F28 Joanne Sorensen F73 Julia Brabant F32 Lisa Thorson F32 Julia Ostrander F15 Nate Muniz M26 Andreas Muschinski M51 Kathryn Ferrel F19 Jon Collis M39 Marina Griffin F9 Justin Bartsch M13 Kaitlyn Blackburn F14 Charlie Heathwood M9 Wyatt Schroth M12 Helen Wright F73 Ylann goresko M13 Lynne Ferguson F43 Lindsay Fetherman F26 Cindy Worster F49 Sheri Nemeth F57 Maximillian Mosier M13 Jasmine Szabo F15 Christine Nelson F35 Min Kim F18 Misty Hildenbrand F27 Deb Hargens F62 Kristi Wade F45 Alys Brockway F48 Audrey Russell F37 Lula DeMars F11 Roger Lapthorne M58 Denise Ashford F53 Carol Finlayson F56 Keith Elliott M29 Linda Ward F59 Catherine Williams F20 Rachelle Fuller F42 Amy Hood F12 Sarah Mooney F16 Beth Brady F58 Rodney Glenn M52 Jacy Kruckenberg F39 Jeffrey Machell M53 William Kohnert M17 Stephanie Ayers F26 Judith W Warner F66 Katie Gann F19 Ginny Page F70 Jennifer Chavez F28 Catherine Trippett F54 Magali Lutz F42 Chandler -

Openairkino 2008

JUNI / JULI 2008 · UNBEZAHLBAR Hindenburger ZEITSCHRIFT FÜR MÖNCHENGLADBACH UND RHEYDT BAUEN & WOHNEN Tag der Architektur GASTRO Gladbachs schönste Biergärten KULTUR MIT Opern unter freiem Himmel GROSSEM Freizeit TERMIN- Freibäder und Baggerseen KALENDER GRILLEN PARTY · KULTUR · MUSIK Rezepte, Grillplätze und Lustiges SPORT · KIDS BORUSSIA Nie mehr zweite Liga! ina menzer boxweltmeisterin aus MG IM INTERVIEW Jazzmatinee So. 15.06.08 Schloss Rheydt Mönchengladbach • Schlossstr. 508 Beginn 11.00 Uhr Eintritt frei. Spenden sind willkommen. Es spielt die Walter‘s Borderland Jazzband Benefizveranstaltung für Kinder in MG Veranstalter: Lions Hilfswerk Mönchengladbach-Rheydt e.V. EDITORIAL MNCHENGLADBACH IM BALD BEFRCHTETEN SOMMERLOCH 2008 Sascha Broich und Marc Thiele, Herausgeber mit exklusiven Immobilien und einen Bau- Auf ins bunte sommerloch! stoffhandel der Extraklasse vor. Barrierefreiheit beginnt im Kopf. Dass es bei vielen von uns noch nicht so weit ist, zeigt liebe leserinnen und leser, ein bewegendes Interview mit einem sym- pathischen Hephata-Bewohner. Norman der Sommer hat noch nicht mal angefan- che Grillplätze unter die Lupe genommen, Hellmann berichtet über Behinderungen im gen, da klagen schon viele über das bald kuriose und interessante Internetseiten re- Alltag. So verständnisvoll, wie wir glauben, bevorstehende Sommerloch. Händler ste- cherchiert und Rezepte für Sie zusammen- sind wir nicht. Wir gucken weg und lassen cken ängstlich ihren Kopf in den Sand und gestellt. Schon mal Bison probiert? Unse- unsere behinderten Mitmenschen alleine. hoffen, dass sie die Flaute heil überstehen re Umfrage sagt Ihnen, wie die Gladbacher anstatt mit tollen Angeboten und sommer- ihre Ferien zuhause verbringen. Dazu gibt Ganz besonders freute uns der Besuch der lichen Aktionen zu locken. Dabei laden die es noch viele Tipps für Kids und einen Über- Box-Weltmeisterin Ina Menzer im Studio un- warmen Sonnenstrahlen doch gerade zum blick über die Bademöglichkeiten in der Re- serer Fotografin Myriam Topel.