Grass Inside This Issue: There Is Not a Sprig of Grass That Shoots Grass 2-3 Uninteresting to Me

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Additional Information

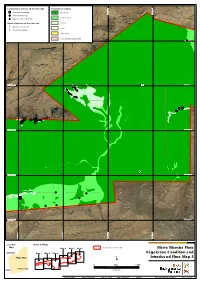

Current Survey Introduced Flora Records Vegetation Condition *Acetosa vesicaria Excellent 534,000 mE 534,000 mE 535,000 534,000 mE 534,000 mE 535,000 534,000 mE 534,000 mE 535,000 534,000 mE 534,000 mE 535,000 534,000 mE 534,000 mE 535,000 534,000 mE 534,000 mE 535,000 534,000 mE 534,000 mE 535,000 536,000 mE 536,000 537,000 mE 537,000 536,000 mE 536,000 537,000 mE 537,000 536,000 mE 536,000 537,000 mE 537,000 536,000 mE 536,000 537,000 mE 537,000 536,000 mE 536,000 537,000 mE 537,000 536,000 mE 536,000 537,000 mE 537,000 536,000 mE 536,000 537,000 mE 537,000 534,000 mE 534,000 mE 535,000 534,000 mE 534,000 mE 535,000 534,000 mE 534,000 mE 535,000 534,000 mE 534,000 mE 535,000 534,000 mE 534,000 mE 535,000 534,000 mE 534,000 mE 535,000 534,000 mE 534,000 mE 535,000 536,000 mE 536,000 537,000 mE 537,000 536,000 mE 536,000 537,000 mE 537,000 536,000 mE 536,000 537,000 mE 537,000 536,000 mE 536,000 537,000 mE 537,000 536,000 mE 536,000 537,000 mE 537,000 536,000 mE 536,000 537,000 mE 537,000 536,000 mE 536,000 537,000 mE 537,000 534,000 mE 534,000 mE 535,000 534,000 mE 534,000 mE 535,000 534,000 mE 534,000 mE 535,000 534,000 mE 534,000 mE 535,000 534,000 mE 534,000 mE 535,000 534,000 mE 534,000 mE 535,000 534,000 mE 534,000 mE 535,000 536,000 mE 536,000 537,000 mE 537,000 536,000 mE 536,000 537,000 mE 537,000 536,000 mE 536,000 537,000 mE 537,000 536,000 mE 536,000 537,000 mE 537,000 536,000 mE 536,000 537,000 mE 537,000 536,000 mE 536,000 537,000 mE 537,000 536,000 mE 536,000 537,000 mE 537,000 534,000 mE 534,000 mE 535,000 534,000 mE 534,000 -

Wiregrass (Aristida Stricta)

Wiregrass (Aristida stricta) For definitions of botanical terms, visit en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Glossary_of_botanical_terms. Wiregrass is a perennial bunchgrass found in scrub, pinelands and coastal uplands throughout much of Florida. It is the dominant groundcover species in longleaf pine savannas and is a primary food source for gopher tortoises. Birds and small wildlife eat the seeds. Historically, cattle grazed on Wiregrass’s tender new growth. Wiregrass flowers are tiny and brown. They are born on spikelike terminal panicles Flower stalks are elongated and extend above the leaves. Leaf blades are long, thin and rolled inward, giving them a wiry appearance (hence the common name). They are erect and green when young Photo courtesy of Alan Cressler, Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center and begin to arch and turn brown as they age. Its fruits are small, yellowish caryopses. Seeds may be dispersed by wind, gravity or on the fur of passing animals. The genus name Aristida is from the Latin arista, meaning “awn” and referring to the three awns or bristle-like structures that extend from the florets. (An alternative common name is Pineland threeawn.) The species epithet, stricta, is from the Latin strictus, meaning straight or erect. Family: Poaceae (Grass family) Native range: Nearly throughout To see where natural populations of Wiregrass have been vouchered, visit www.florida.plantatlas.usf.edu. Hardiness: Zones 8A–10B Lifespan: Perennial Soil: Moist to dry, well-drained sandy soils Exposure: Full sun to partial shade Growth habit: 1–3’+ tall and equally wide Propagation: Division, seed Garden tips: Wiregrass is fast-growing and tolerant of drought conditions and low-nutrient soils. -

A Vegetation Map of the Valles Caldera National Preserve, New

______________________________________________________________________________ A Vegetation Map of the Valles Caldera National Preserve, New Mexico ______________________________________________________________________________ A Vegetation Map of Valles Caldera National Preserve, New Mexico 1 Esteban Muldavin, Paul Neville, Charlie Jackson, and Teri Neville2 2006 ______________________________________________________________________________ SUMMARY To support the management and sustainability of the ecosystems of the Valles Caldera National Preserve (VCNP), a map of current vegetation was developed. The map was based on aerial photography from 2000 and Landsat satellite imagery from 1999 and 2001, and was designed to serve natural resources management planning activities at an operational scale of 1:24,000. There are 20 map units distributed among forest, shrubland, grassland, and wetland ecosystems. Each map unit is defined in terms of a vegetation classification that was developed for the preserve based on 348 ground plots. An annotated legend is provided with details of vegetation composition, environment, and distribution of each unit in the preserve. Map sheets at 1:32,000 scale were produced, and a stand-alone geographic information system was constructed to house the digital version of the map. In addition, all supporting field data was compiled into a relational database for use by preserve managers. Cerro La Jarra in Valle Grande of the Valles Caldera National Preserve (Photo: E. Muldavin) 1 Final report submitted in April 4, 2006 in partial fulfillment of National Prak Service Award No. 1443-CA-1248- 01-001 and Valles Caldrea Trust Contract No. VCT-TO 0401. 2 Esteban Muldavin (Senior Ecologist), Charlie Jackson (Mapping Specialist), and Teri Neville (GIS Specialist) are with Natural Heritage New Mexico of the Museum of Southwestern Biology at the University of New Mexico (UNM); Paul Neville is with the Earth Data Analysis Center (EDAC) at UNM. -

December 2012 Number 1

Calochortiana December 2012 Number 1 December 2012 Number 1 CONTENTS Proceedings of the Fifth South- western Rare and Endangered Plant Conference Calochortiana, a new publication of the Utah Native Plant Society . 3 The Fifth Southwestern Rare and En- dangered Plant Conference, Salt Lake City, Utah, March 2009 . 3 Abstracts of presentations and posters not submitted for the proceedings . 4 Southwestern cienegas: Rare habitats for endangered wetland plants. Robert Sivinski . 17 A new look at ranking plant rarity for conservation purposes, with an em- phasis on the flora of the American Southwest. John R. Spence . 25 The contribution of Cedar Breaks Na- tional Monument to the conservation of vascular plant diversity in Utah. Walter Fertig and Douglas N. Rey- nolds . 35 Studying the seed bank dynamics of rare plants. Susan Meyer . 46 East meets west: Rare desert Alliums in Arizona. John L. Anderson . 56 Calochortus nuttallii (Sego lily), Spatial patterns of endemic plant spe- state flower of Utah. By Kaye cies of the Colorado Plateau. Crystal Thorne. Krause . 63 Continued on page 2 Copyright 2012 Utah Native Plant Society. All Rights Reserved. Utah Native Plant Society Utah Native Plant Society, PO Box 520041, Salt Lake Copyright 2012 Utah Native Plant Society. All Rights City, Utah, 84152-0041. www.unps.org Reserved. Calochortiana is a publication of the Utah Native Plant Society, a 501(c)(3) not-for-profit organi- Editor: Walter Fertig ([email protected]), zation dedicated to conserving and promoting steward- Editorial Committee: Walter Fertig, Mindy Wheeler, ship of our native plants. Leila Shultz, and Susan Meyer CONTENTS, continued Biogeography of rare plants of the Ash Meadows National Wildlife Refuge, Nevada. -

Responses of Plant Communities to Grazing in the Southwestern United States Department of Agriculture United States Forest Service

Responses of Plant Communities to Grazing in the Southwestern United States Department of Agriculture United States Forest Service Rocky Mountain Research Station Daniel G. Milchunas General Technical Report RMRS-GTR-169 April 2006 Milchunas, Daniel G. 2006. Responses of plant communities to grazing in the southwestern United States. Gen. Tech. Rep. RMRS-GTR-169. Fort Collins, CO: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station. 126 p. Abstract Grazing by wild and domestic mammals can have small to large effects on plant communities, depend- ing on characteristics of the particular community and of the type and intensity of grazing. The broad objective of this report was to extensively review literature on the effects of grazing on 25 plant commu- nities of the southwestern U.S. in terms of plant species composition, aboveground primary productiv- ity, and root and soil attributes. Livestock grazing management and grazing systems are assessed, as are effects of small and large native mammals and feral species, when data are available. Emphasis is placed on the evolutionary history of grazing and productivity of the particular communities as deter- minants of response. After reviewing available studies for each community type, we compare changes in species composition with grazing among community types. Comparisons are also made between southwestern communities with a relatively short history of grazing and communities of the adjacent Great Plains with a long evolutionary history of grazing. Evidence for grazing as a factor in shifts from grasslands to shrublands is considered. An appendix outlines a new community classification system, which is followed in describing grazing impacts in prior sections. -

Department of the Interior Fish and Wildlife Service

Tuesday, February 10, 2009 Part II Department of the Interior Fish and Wildlife Service 50 CFR Part 17 Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants; Determination of Endangered Status for Reticulated Flatwoods Salamander; Designation of Critical Habitat for Frosted Flatwoods Salamander and Reticulated Flatwoods Salamander; Final Rule VerDate Nov<24>2008 14:17 Feb 09, 2009 Jkt 217001 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 4717 Sfmt 4717 E:\FR\FM\10FER2.SGM 10FER2 erowe on PROD1PC63 with RULES_2 6700 Federal Register / Vol. 74, No. 26 / Tuesday, February 10, 2009 / Rules and Regulations DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR during normal business hours, at U.S. Register on or before July 30, 2008, with Fish and Wildlife Service, Mississippi the final critical habitat rule to be Fish and Wildlife Service Fish and Wildlife Office, 6578 Dogwood submitted for publication in the Federal View Parkway, Jackson, MS 39213. Register by January 30, 2009. The 50 CFR Part 17 FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT: Ray revised proposed rule was signed on [FWS–R4–ES–2008–0082; MO 9921050083– Aycock, Field Supervisor, U.S. Fish and and delivered to the Federal Register on B2] Wildlife Service, Mississippi Field July 30, 2008, and it subsequently Office, 6578 Dogwood View Parkway, published on August 13, 2008 (73 FR RIN 1018–AU85 Jackson, MS 39213; telephone: 601– 47258). We also published supplemental information on the Endangered and Threatened Wildlife 321–1122; facsimile: 601–965–4340. If proposed rule to maintain the status of and Plants; Determination of you use a telecommunications device the frosted flatwoods salamander as Endangered Status for Reticulated for the deaf (TDD), call the Federal Information Relay Service (FIRS) at threatened (73 FR 54125; September 18, Flatwoods Salamander; Designation of 2008). -

PDF Handbook Download

Navajo Nation Range Management . Handbook .~/ ·- .!-.:., ~~,-;--... ·-... r#~/ Frank Parrill Range Conservationist Navajo Tribe Window Rock, Arizona Allan H Blacksheep, Jr. Agricultural Extension Agent The University of Arizona Ft. Defiance, Arizona Cooperative Extension Service The University of Arizona T81104 Needle-and-threadgrass Stipa comata Atsábik’a’ítł’oh This handbook is dedicated to the memory of Alex Tsosie, Soil Conservationist with the Bureau of Indian Affairs in Window Rock. Alex had a deep love for his Navajo land and its livestock. He had the desire to both improve the future of his land and to stay close to the culture of his ancestors. His dedication to the care of the lands will always be an inspiration to those of us who knew and worked with him. Alex, we are glad that you passed among us. May your moccasins always walk in the soft green grass and may you never thirst for cool, clear water. Amen. The Navajo Nation Range Management Handbook has been developed through the efforts of many individuals. The original manuscript was drafted by Frank Parrill, range conservationist for the Navajo tribe, Window Rock, Arizona. Special acknowledgment is due to Joanne Manygoats, range technician for the tribe, who provided valuable assistance in supplying Navajo names for the plants listed in the publication and proofreading the type. Leo Beno, also a range conservationist for the tribe, served as technical consultant. At The University of Arizona, Dr. David Bryant, Extension range management specialist and professor in the School of Renewable Natural Resources, critically reviewed the preliminary manuscript and provided valuable experience and practical insights that are incorporated in the publication. -

Jan Dvorak (As Quickly Written Down by a Person with Poor Hearing…Me)

1/22/2018 The Impact of Polyploidy on Genome Evolution in Poales and Other Monocots “I don’t have to emphasize that gene duplications are the fabric of evolution in plants.” -Jan Dvorak (as quickly written down by a person with poor hearing…me) Michael R. McKain The University of Alabama @mrmckain @mrmckain Poales Diversity Grass genomes: the choose your own adventure of genome evolution • ~22,800 species • ~11,088 species in Poaceae • Transposons (McClintock, Wessler) • GC content bias (Carels and Bernardi 2000) • Three WGD events 0 0 4 0 0 • rho (Peterson et al. 2004) 3 y c n 0 e 0 u 2 q e r F • 0 sigma (Tang et al. 2010) 0 1 • tau (Tang et al. 2010, Jiao et al. 2014) 0 %GC Givnish et al. 2010 @mrmckain Schnable et al., 2009 Zeroing in on WGD placement Banana genome Pineapple genome How has ancient polyploidy altered the genomic landscape in grasses and other Poales? D’Hont et al. 2012 Ming, VanBuren et al. 2015 Recovered sigma after grass divergence from commelinids Recovered sigma after grass+pineapple divergence from commelinids @mrmckain @mrmckain 1 1/22/2018 Phylotranscriptomic approach Coalescence-based Phylogeny of 234 Single-copy genes • Sampling 27 transcriptomes and 7 genomes • Phylogeny consistent with previous • Representation for all families (except Thurniaceae) in nuclear gene results Poales • Conflicting topology with • RNA from young leaf or apical meristem, a combination of chloroplast genome tree: Moncot Tree of Life and 1KP • Ecdeiocolea/Joinvillea sister instead of • General steps: a grade • Trinity assembly • Typha -

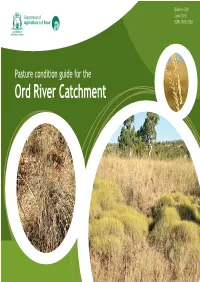

Pasture Condition Guide for the Ord River Catchment

Bulletin 4769 Department of June 2009 Agriculture and Food ISSN 1833-7236 Pasture condition guide for the Ord River Catchment Department of Agriculture and Food Pasture condition guide for the Ord River Catchment K. Ryan, E. Tierney & P. Novelly Copyright © Western Australian Agriculture Authority, 2009 Acknowledgements Photographs by S. Eyres and the Department of Agriculture and Food, Western Australia (DAFWA) Photographic Unit The information in this publication has been developed in consultation with experienced rangelands field staff providing services to the East Kimberley pastoral leases and with reference to Range Condition Guides for the West Kimberley Area, WA (Payne, Kubicki and Wilcox 1974) and Lands of the Ord–Victoria Area, WA and NT (Stewart et al. 1970). The authors would like to thank all those who provided valuable feedback on the design and content of this guide, including Andrew Craig, David Hadden and Matthew Fletcher (DAFWA Kununurra), Simon Eyres (DAFWA Photographic Unit), Alan Payne (retired DAFWA rangelands advisor), and members of the Halls Creek—East Kimberley Land Conservation District. This project was funded by Rangelands NRM WA using National Action Plan for Salinity and Water Quality funding. Rangelands NRM WA regards this project as a strategic investment which will contribute to an improved understanding and awareness of pasture condition in the Ord Catchment, leading to improved land management in that area. Rangelands NRM WA contracted the Department of Agriculture and Food WA to undertake the project. Funding for the National Action Plan for Salinity and Water Quality was provided by the Australian and Western Australian Governments. Disclaimer The Chief Executive Officer of the Department of Agriculture and Food and the State of Western Australia accept no liability whatsoever by reason of negligence or otherwise arising from the use or release of this information or any part of it. -

List of Plants for Great Sand Dunes National Park and Preserve

Great Sand Dunes National Park and Preserve Plant Checklist DRAFT as of 29 November 2005 FERNS AND FERN ALLIES Equisetaceae (Horsetail Family) Vascular Plant Equisetales Equisetaceae Equisetum arvense Present in Park Rare Native Field horsetail Vascular Plant Equisetales Equisetaceae Equisetum laevigatum Present in Park Unknown Native Scouring-rush Polypodiaceae (Fern Family) Vascular Plant Polypodiales Dryopteridaceae Cystopteris fragilis Present in Park Uncommon Native Brittle bladderfern Vascular Plant Polypodiales Dryopteridaceae Woodsia oregana Present in Park Uncommon Native Oregon woodsia Pteridaceae (Maidenhair Fern Family) Vascular Plant Polypodiales Pteridaceae Argyrochosma fendleri Present in Park Unknown Native Zigzag fern Vascular Plant Polypodiales Pteridaceae Cheilanthes feei Present in Park Uncommon Native Slender lip fern Vascular Plant Polypodiales Pteridaceae Cryptogramma acrostichoides Present in Park Unknown Native American rockbrake Selaginellaceae (Spikemoss Family) Vascular Plant Selaginellales Selaginellaceae Selaginella densa Present in Park Rare Native Lesser spikemoss Vascular Plant Selaginellales Selaginellaceae Selaginella weatherbiana Present in Park Unknown Native Weatherby's clubmoss CONIFERS Cupressaceae (Cypress family) Vascular Plant Pinales Cupressaceae Juniperus scopulorum Present in Park Unknown Native Rocky Mountain juniper Pinaceae (Pine Family) Vascular Plant Pinales Pinaceae Abies concolor var. concolor Present in Park Rare Native White fir Vascular Plant Pinales Pinaceae Abies lasiocarpa Present -

New Mexico Range Plants

New Mexico Range Plants Circular 374 Revised by Christopher D. Allison and Nick Ashcroft1 Cooperative Extension Service • College of Agricultural, Consumer and Environmental Sciences New Mexico contains almost 78 million acres, more than 90 percent of which is in native vegetation grazed by domestic livestock and wildlife. The kinds of plants that grow on a range, along with their quality and quan- tity, determine its value. A successful rancher knows the plants on his or her range. There are more than 3,000 species of plants in New Mexico. The 85 discussed here are most important to the livestock industry. Most of these are native plants. RANGELAND AREAS OF NEW MEXICO Figure 1 represents the major rangeland areas in New Mexico. The northern desert, western plateau, and high valley areas are enough alike to be described together, as are the central and high plains areas and the southern desert and basin. Southern Desert and Basin 36 - New Mexico and Arizona Plateaus and Mesas 37 - San Juan River Valley, mesas and Plateaus The southern desert and basin occupies much of south- 39 - Arizona and New Mexico Mountains 41 - Southeastern Arizona Basin and Range 42 - Southern Desertic Basins, Plains and Mountains ern New Mexico at elevations between 3,000 and 5,000 48 - Southern Rocky Mountains 51 - High Intermountain Valleys feet. This area follows the Rio Grande north into the 70 - Pecos/Canadian Plains and Valleys southern part of Sandoval County. 77 - Southern High Plains Some of the most common plants are creosote bush (Larrea tridentata [DC.] Coville), mesquite (Prosopis Figure 1. -

Plant Propagation Protocol for Aristida Purpurea TAXONOMY Plant

Plant Propagation Protocol for Aristida purpurea ESRM 412 – Native Plant Production Spring 2017 Source: https://farm8.staticflickr.com/7315/9704303264_b5e8db6e48_b.jpg TAXONOMY Plant Family Scientific Name Poaceae Common Name Grasses Species Scientific Name Scientific Name Aristida purpurea Nutt. Varieties purpurea, longiseta (Steud.) Vasey, fendleriana (Steud.) Vasey Sub-species Cultivar Common Synonym(s) ARPUF Aristida purpurea Nutt. var. fendleriana (Steud.) Vasey ARPUL Aristida purpurea Nutt. var. longiseta (Steud.) Vasey Common Name(s) wiregrass, red threeawn, dogtown grass, prairie threeawn, purple threeawn Species Code (as per USDA ARPU9 Plants database) GENERAL INFORMATION Geographical range Purple threeawn is found spread out in northwestern part of the US as far west as the coast, but they have been found spreading east all the way to Illinois Ecological distribution Found inhabiting dry coarse or sandy soils in either desert valleys or along foothills. Climate and elevation range They tend to grow as low as the coastal elevations all the way up to 7000 feet. They ideally like dry soils. Although they have adapted to be drought tolerant, they can also tolerate precipitation over 6 inches. However, growth isn’t optimal when high levels of precipitation are present. They can also survive in temperatures as low as -20 degree F. (Calscape) Local habitat and abundance They are found growing in plant communities that including: creosote bush, blackbrush, shadscale, greasewood, pinyon- juniper and ponderosa pine. Often considered a good understory grass layer. They tend to also invade roadsides and cover up animal burrows as they spread. (USDA) Plant strategy type / They’re often found growing alongside other grasses and shrubs.