1. Introduction Regional Disparities Die Hard

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Celso Furtado, 100 Anos: a Operação Nordeste

76 economia & história: especial Celso Furtado Celso Furtado, 100 anos: A Operação Nordeste Gustavo Louis Henrique Pinto (*) O período entre 1958 e 1964 na trajetória de Celso era, segundo o próprio Furtado (1997, p. 65) aponta, Furtado pode ser interpretado como o principal mo- mover-se politicamente na construção de um plano mento de ação política deste pensador e de construção de ação para a região que mitigasse os efeitos da seca de um projeto furtadiano de desenvolvimento nacio- rigorosa de 1958 e dos resultados das eleições para nal e regional. Após uma década de trabalhos realiza- governadores, já que a oposição ao presidente vencera dos na Comissão Econômica para a América Latina e em estados como Pernambuco e Bahia. Caribe (1949-1957), grande parte à frente da Diretoria da Divisão de Desenvolvimento, Furtado retorna para conjunto de ações como Operação Nordeste era a Furtado (1997, p. 80) afirma que a nomeação deste como pesquisador fellow em Cambridge, no King’s Col- cristalização de mais um slogan por Kubitschek, que lege,o Brasil onde em produziu agosto de sua 1958, obra ao Formação final do seueconômica ano letivo do repetia a tentativa feita anteriormente com a Opera- Brasil. Chega ao país para desempenhar uma das atu- ção Pan-Americana, mas agora com a inserção da re- ações políticas nacionais mais marcantes gião Nordeste “no grande debate sobre o desenvolvimento do país”. A necessidade nas ações de coordenação da Operação política de Kubitschek se associa ao em- Nordeste,das décadas que de resultou 1950 e 1960, na construção configurada da penho intelectual de Furtado, desejoso de Superintendência do Desenvolvimento do implementar sua experiência cepalina em Nordeste (Sudene). -

Icthyofauna from Streams of Barro Alto and Niquelândia, Upper Tocantins River Basin, Goiás State, Brazil

Icthyofauna from streams of Barro Alto and Niquelândia, upper Tocantins River Basin, Goiás State, Brazil THIAGO B VIEIRA¹*, LUCIANO C LAJOVICK², CAIO STUART3 & ROGÉRIO P BASTOS4 ¹ Laboratório de Ictiologia de Altamira, Universidade Federal do Para – LIA UFPA e Programa de Pós- Graduação em Biodiversidade e Conservação – PPGBC, Universidade Federal do Pará (UFPA), Campus Altamira. Rua Coronel José Porfírio 2515, São Sebastião, Altamira, PA. CEP 68372-040, Brasil; [email protected] ² Programa de Pós-graduação em Ecologia e Evolução, Departamento de Ecologia, ICB, UFG, Caixa postal 131, Goiânia, GO, Brasil, CEP 74001-970. [email protected] 3 Instituto de Pesquisas Ambientais e Ações IPAAC Rua 34 qd a24 Lt 21a Jardim Goiás Goiânia - Goiás CEP 74805-370. [email protected] 4 Laboratório de Herpetologia e Comportamento Animal, Departamento de Ecologia, ICB, UFG, Caixa postal 131, Goiânia, GO, Brasil, CEP 74001-970. [email protected] *Corresponding author: [email protected] Abstract: In face of the accelerated degradation of streams located within the Brazilian Cerrado, the knowledge of distribution patterns is very important to aid conservation strategies. The aim of this work is to increase the knowledge of the stream’s fish fauna in the State of Goiás, Brazil. 12 streams from the municipalities of Barro Alto and Niquelândia were sampled with trawl nets. During this study, 1247 fishes belonging to 27 species, 11 families, and three orders were collected. Characiformes comprised 1164 specimens of the sampled fishes, the most abundant order, while Perciformes was the less abundant order, with 17 collected specimens. Perciformes fishes were registered only in streams from Niquelândia. Astyanax elachylepis, Bryconops alburnoides and Astyanax aff. -

Epidemiological Update Yellow Fever

Epidemiological Update Yellow Fever 9 March 2017 Situation summary in the Americas Since epidemiological week (EW) 1 to EW 8 of 2017, Brazil, Colombia, Peru, and the Plurinational State of Bolivia, have reported suspected and confirmed yellow fever cases. The following is a situation summary in Brazil. In Brazil, since the beginning of the outbreak in December 2016 to EW 9 of 2017, there were 1,500 cases of yellow fever reported (371 confirmed, 163 discarded, and 966 suspected cases remain under investigation), including 241 deaths (127 confirmed, 8 discarded, and 106 under investigation). The case fatality rate (CFR) is 34% among confirmed cases and 11% among suspected cases. According to the probable site of infection, 79% of the suspected and confirmed cases were reported in the state of Minas Gerais (1,057), followed by Espírito Santo (226), São Paulo (15), Bahia (7), Tocantins (6), Goías (1) and Rio Grande do Norte (1).1 The confirmed cases are distributed in three states: Minas Gerais (288), Espírito Santo (79), and São Paulo (4). Figure 1 illustrates the municipalities with confirmed cases and cases under investigation, as well as confirmed epizootics, and epizootics under investigation. In the state of Minas Gerais, the downward trend in suspected and confirmed cases continues to decline for the fourth consecutive week. Meanwhile, in the state of Espírito Santo cases have increased from EW 1 to EW 4 of 2017 and it will be necessary to continue to observe the evolution of the epidemic (Figure 2). With regard to the number of new cases (confirmed and under investigation) reported between 6 February and 6 March, there were 137 new cases in Espírito Santo and in Minas Gerais during the same period there were 239 new cases reported. -

Tocantins, Brazil

Tocantins, Brazil Jurisdictional indicators brief State area: 277,721 km² (3.26% of Brazil) Original forest area: 39,853 km² Current forest area (2019): 9,964 km² (3.6% of Tocantins) Yearly deforestation (2019) 23 km² Yearly deforestation rate (2019) 0.23% Interannual deforestation change -8% (2018-2019) Accumulated deforestation (2001-2019): 1,800 km² Protected conservation areas: 38,548 km² (13.9% of Tocantins) Carbon stocks (2015): 62 millions tons (above ground biomass) Representative crops (2018): Sugarcane (3,106,492 tons); Soybean (2,667,936 tons); Rice (659,809 tons) Value of agricultural production (2016): $1,152,935,462 USD More on jurisdictional sustainability State of jurisdictional sustainability Index: Forest and people | Deforestation | Burned area | Emissions from deforestation | Livestock | Agriculture | Aquaculture Forest and people In 2019, the estimated area of tropical forest in the state of Tocantins was 9,964 km2, equivalent to 3.6% of the state’s total area, and to 0.3% of the tropical forest remaining in the nine states of the Brazilian legal Amazon. The total accumulated forest lost during the period 2001-2019 was 1,800 km2, equivalent to 16.1% of the forest area remaining in 2001. Tocantins concentrated about 0.2% of the carbon reserves stored in the biomass of the Brazilian tropical forest (about 62 mt C as of 2019). a b 100% 3.6% of the state is covered with forest DRAFT80% 60% 0.3% of Brazilian tropical forest area 40% 20% 0.2% of Brazilian tropical forest carbon stock 3.6% 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 2001 2019 No forest (%) Deforestation (%) Forest (%) Figure 1: a) forest share and b) transition of forest to deforestation over the last years There were 1.6 million people living in Tocantins as of 2020, distributed in 19 municipalities, with 0.3 million people living in the capital city of Palmas. -

Green Economy in Amapá State, Brazil Progress and Perspectives

Green economy in Amapá State, Brazil Progress and perspectives Virgilio Viana, Cecilia Viana, Ana Euler, Maryanne Grieg-Gran and Steve Bass Country Report Green economy Keywords: June 2014 green growth; green economy policy; environmental economics; participation; payments for environmental services About the author Virgilio Viana is Chief Executive of the Fundação Amazonas Sustentável (Sustainable Amazonas Foundation) and International Fellow of IIED Cecilia Viana is a consultant and a doctoral student at the Center for Sustainable Development, University of Brasília Ana Euler is President-Director of the Amapá State Forestry Institute and Researcher at Embrapa-AP Maryanne Grieg-Gran is Principal Researcher (Economics) at IIED Steve Bass is Head of IIED’s Sustainable Markets Group Acknowledgements We would like to thank the many participants at the two seminars on green economy in Amapá held in Macapá in March 2012 and March 2013, for their ideas and enthusiasm; the staff of the Fundação Amazonas Sustentável for organising the trip of Amapá government staff to Amazonas; and Laura Jenks of IIED for editorial and project management assistance. The work was made possible by financial support to IIED from UK Aid; however the opinions in this paper are not necessarily those of the UK Government. Produced by IIED’s Sustainable Markets Group The Sustainable Markets Group drives IIED’s efforts to ensure that markets contribute to positive social, environmental and economic outcomes. The group brings together IIED’s work on market governance, business models, market failure, consumption, investment and the economics of climate change. Published by IIED, June 2014 Virgilio Viana, Cecilia Viana, Ana Euler, Maryanne Grieg-Gran and Steve Bass. -

FINANCIAL STATEMENTS Bank And

FINANCIAL STATEMENTS Bank and FNE Position: 30.06.2017 Management Report – 1st half of 2017 1. A WORD FROM THE CEO Banco do Nordeste responds robustly to the challenges faced in a still adverse economic scenario. In the first half of 2017, Banco do Nordeste contracted 2.4 million transactions and injected R$ 11.2 billion in the economy in the northeast region of Brazil, which corresponds to an increase by 3.6% as compared with the first half of 2016. This was mostly directed to investments of a rural, industrial, agro-industrial, infrastructure, sales and services nature, in the amount of R$ 6.7 billion referring to long-term operations, which corresponds to approximately 60% of the total transactions contracted. In the first half of 2017, R$ 4.85 billion financed urban and rural micro entrepreneurs providing long and short-term credit, by means of the largest microcredit-oriented programs in Latin America, Crediamigo and Agroamigo. Key instruments for reducing inequalities and that constitute a way out of poverty, these programs allocate to the northeast region approximately 67% of the amount invested in the Brazilian monthly family stipend program [Bolsa Família], provide inclusion, social development and make a difference in people’s lives. In the first six months of the year, the Bank recovered R$ 2.6 billion unpaid receivables, 237.88% above the amount recovered in the first half of 2016. Over 100 thousand transactions were regularized, most of which deriving from the benefits of Law No. 13340/16, which allows rural debts to be renegotiated. The Bank held the I Fórum BNB de Infraestrutura [I BNB Infrastructure Forum], an event that gathered market agents and public managers from all over the Northeast region to map projects that can be financed by the FNE Infraestrutura Program. -

An Analysis of the Evolution of Socioeconomic Inequality in Brazilian States Since 1976 †

sustainability Article Through the Irregular Paths of Inequality: An Analysis of the Evolution of Socioeconomic Inequality in Brazilian States Since 1976 † Paulo Mourao 1,* and Alexandre Junqueira 2 1 School of Management and Economics & NIPE, Minho University, 4710-057 Braga, Portugal 2 School of Management and Economics, Minho University, 4710-57 Braga, Portugal; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] † Authors acknowledge the contribution of two anonymous reviewers on a previous version of this research. Remaining limitations are authors’ exclusive ones. Abstract: Patterns of inequality tend to seriously undermine any attempt at economic growth policy when the inequality is perceived by significant groups of individuals as unjust, inhuman, and insurmountable. One country with a high degree of inequality has been Brazil (usually in the world top-10). Brazil had also witnessed strong dynamics of certain indicators, such as the Gini coefficient, over the last several decades. However, so far, such dynamics have not been properly analyzed, especially considering the significant differences across Brazilian states. For filling that gap, this study used econometric techniques specific to time series and tried to identify structural breaks in the series of Gini coefficients for the 27 Brazilian states since 1976. Results showed a tendency towards an increase in inequality until 1995, followed by a reduction in inequality since 2000. Some cases of Brazilian states were related to the absence of structural breaks, showing a maintenance of historical trends in the evolution of inequality, which raises important policies’ challenges. Citation: Mourao, P.; Junqueira, A. Through the Irregular Paths of Keywords: inequality; Gini coefficient; structural breaks; Brazil Inequality: An Analysis of the Evolution of Socioeconomic Inequality in Brazilian States Since 1976 . -

SERGIPE 2018: BREAST HEALTHCARE ASSESSMENT an Assessment of Breast Cancer Early Detection, Diagnosis and Treatment in Sergipe, Brazil

SERGIPE 2018: BREAST HEALTHCARE ASSESSMENT An Assessment of Breast Cancer Early Detection, Diagnosis and Treatment in Sergipe, Brazil SERGIPE 2018: BREAST HEALTHCARE ASSESSMENT AN ASSESSMENT OF BREAST CANCER EARLY DETECTION, DIAGNOSIS AND TREATMENT IN SERGIPE, BRAZIL A report prepared by the Breast Health Global Initiative for Susan G. Komen® in support of the Breast Cancer Initiative 2.5 campaign. Breast Health Global Initiative Executive Summary Background: In 1990, the objectives set forth in the survivors were interviewed about their experiences Brazilian Constitution of 1988 were consolidated to related to health service delivery in the public and create the publicly funded health system Sistema Único private sectors. The tools and strategies used for the de Saúde (SUS). Since then, investments in the health assessment were developed and adapted to local needs system and guaranteed access to universal healthcare by BCI2.5 and Susan G. Komen. The data informed a have translated into lower rates of communicable resource-appropriate phased implementation plan to diseases and maternal and infant mortality rates. improve breast cancer early detection, diagnosis and Like other upper-middle income countries, Brazil is treatment in Sergipe. experiencing an epidemiological transition where incidence and mortality rates from non-communicable Key findings: SUS provides free healthcare for all diseases including breast cancer, have been steadily women in Sergipe, including breast health. Prevention, increasing. In 2004, the government of Brazil issued a epidemiological surveillance, treatment, information, Consensus Statement — Controle do Câncer de Mama: education and research activities are led by Brazil’s Documento de Consenso—for the management of Instituto Nacional de Cancer (INCA)—the National Cancer breast cancer. -

Social Distancing Measures in the Fight Against COVID-19 in Brazil

ARTIGO ARTICLE Medidas de distanciamento social para o enfrentamento da COVID-19 no Brasil: caracterização e análise epidemiológica por estado Social distancing measures in the fight against COVID-19 in Brazil: description and epidemiological analysis by state Lara Lívia Santos da Silva 1 Alex Felipe Rodrigues Lima 2 Medidas de distanciamiento social para el Démerson André Polli 3 Paulo Fellipe Silvério Razia 1 combate a la COVID-19 en Brasil: caracterización Luis Felipe Alvim Pavão 4 y análisis epidemiológico por estado Marco Antônio Freitas de Hollanda Cavalcanti 5 Cristiana Maria Toscano 1 doi: 10.1590/0102-311X00185020 Resumo Correspondência L. L. S. Silva Universidade Federal de Goiás. Medidas de distanciamento social vêm sendo amplamente adotadas para mi- Rua 235 s/n, Setor Leste Universitário, Goiânia, GO tigar a pandemia da COVID-19. No entanto, pouco se sabe quanto ao seu 74605-050, Brasil. impacto no momento da implementação, abrangência e duração da vigência [email protected] das medidas. O objetivo deste estudo foi caracterizar as medidas de distan- 1 ciamento social implementadas pelas Unidades da Federação (UF) brasileiras, Universidade Federal de Goiás, Goiânia, Brasil. 2 Instituto Mauro Borges de Estatística e Estudos incluindo o tipo de medida e o momento de sua adoção. Trata-se de um estudo Socioeconômicos, Goiânia, Brasil. descritivo com caracterização do tipo, momento cronológico e epidemiológico 3 Universidade de Brasília, Brasília, Brasil. da implementação e abrangência das medidas. O levantamento das medidas 4 Secretaria do Tesouro Nacional, Brasília, Brasil. foi realizado por meio de buscas em sites oficiais das Secretarias de Governo 5 Instituto de Pesquisa Econômica Aplicada, Rio de Janeiro, Brasil. -

Birding in North-East Brazil, Part 2: the Vast State of Bahia Ciro Albano

>> BIRDING SITES BIRDING NORTH-EAST BRAZIL: BAHIA Birding in north-east Brazil, part 2: The vast state of Bahia Ciro Albano No birder can feel satisfied without ever visiting the country of Brazil, home to over half of the Neotropical avifauna. In this second and final part on top birding places in north-east Brazil, the author makes this point abundantly clear… What are you waiting for? Male Hooded Visorbearer Augastes lumachella (Near threatened), morro do pai inácio, february 2010. Endemic to the state of Bahia and found on mountain- tops of the Chapada Diamantina All photos are by Ciro Albano/www.nebrazilbirding.com and were taken in north-east Brazil 49 neotropical birding 7 neotropical birding 7 49 >> BIRDING SITES BIRDING NORTH-EAST BRAZIL: BAHIA ontinuing with the second part of the shouldered Fire-eye Pyriglena leucoptera, article published in Neotropical Birding White-bibbed Antbird Myrmeciza loricata and C 62 here I describe the state of Bahia; an others. Cerrado specialities include Collared outstanding destination for birdwatching in Brazil. Crescentchest Melanopareia torquata, Rufous- The state is huge (565 million km²) and contains sided Pygmy Tyrant Euscarthmus rufomarginatus an incredible diversity of habitats, ranging from (Near Threatened), the beautiful Horned Sungem lowlands to montane Atlantic Forest, Caatinga, Heliactin bilophus and White-banded Tanager semi-deciduous forest and several Cerrado types. Neothraupis fasciata (Near Threatened). Campo A total of almost 800 species has been recorded rupestre birds include Gray-backed Tachuri in the state6, which harbours 33 Important Bird Polystictus superciliaris (Near Threatened) Areas (IBAs)3 and six Endemic Bird Areas (EBAs)7. -

Roraima State Site Profiling. Boa Vista and Pacaraima, Roraima State

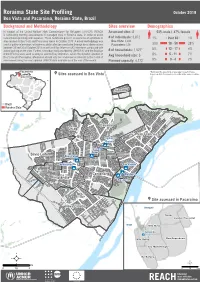

Roraima State Site Profiling October 2018 Boa Vista and Pacaraima, Roraima State, Brazil Background and Methodology Sites overview Demographics In support of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), REACH Assessed sites: 8 53% male / 47% female 1+28+4+7+7 is conducting monthly assessments in managed sites in Roraima state, in order to assist 1+30+5+8+9 humanitarian planning and response. These factsheets present an overview of conditions in # of individuals: 3,872 1% 0ver 60 1% sites located in Boa Vista and Pacaraima towns in October 2018. A mixed methodology was Boa Vista: 3,444 used to gather information, with primary data collection conducted through direct observations Pacaraima: 428 30% 18 - 59 28% between 29 and 30 of October 2018 as well as 8 Key Informant (KI) interviews conducted with 5% 12 - 17 4% actors working on the sites. Further, secondary data provided by UNHCR KI and the Brazilian # of households: 1,527* Armed Forces were used to analyse selected key indicators. Given the dynamic situation in Avg household size: 3 8% 5 - 11 7% Boa Vista and Pacaraima, information should only be considered as relevant to the month of assessment using the most updated UNHCR data available as of the end of the month. Planned capacity: 4,172 9% 0 - 4 7% !(Pacaraima *Estimated by assuming an average household size, !( ¥Sites assessed in Boa Vista based on data from previous rounds in the same location. Boa Vista Cauamé Brazil Roraima State Cauamé União São Francisco Jardim Floresta ÔÆ Tancredo Neves Silvio Leite Nova Canaã ÔÆ ÔÆ Pintolândia São Vicente ÔÆ ÔÆ ÔÆ Centenário ÔÆ Rondon 1 Pintolândia Rondon 3 ¥Site assessed in Pacaraima Nova Cidade Venezuela Suapi Jardim Florestal Brazil Vila Nova Janokoida ÔÆ Das Orquídeas Vila Velha Ilzo Montenegro Da Balança ² ² km m 0 1,5 3 0 500 1.000 Fundo de População das Nações Unidas União Europeia Roraima site profiling October 2018 Jardim Floresta Boa Vista, Roraima State, Brazil Lat. -

The Relevance of the Cerrado's Water

THE RELEVANCE OF THE CERRADO’S WATER RESOURCES TO THE BRAZILIAN DEVELOPMENT Jorge Enoch Furquim Werneck Lima1; Euzebio Medrado da Silva1; Eduardo Cyrino Oliveira-Filho1; Eder de Souza Martins1; Adriana Reatto1; Vinicius Bof Bufon1 1 Embrapa Cerrados, BR 020, km 18, Planaltina, Federal District, Brazil, 70670-305. E-mail: [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected] ABSTRACT: The Cerrado (Brazilian savanna) is the second largest Brazilian biome (204 million hectares) and due to its location in the Brazilian Central Plateau it plays an important role in terms of water production and distribution throughout the country. Eight of the twelve Brazilian hydrographic regions receive water from this Biome. It contributes to more than 90% of the discharge of the São Francisco River, 50% of the Paraná River, and 70% of the Tocantins River. Therefore, the Cerrado is a strategic region for the national hydropower sector, being responsible for more than 50% of the Brazilian hydroelectricity production. Furthermore, it has an outstanding relevance in the national agricultural scenery. Despite of the relatively abundance of water in most of the region, water conflicts are beginning to arise in some areas. The objective of this paper is to discuss the economical and ecological relevance of the water resources of the Cerrado. Key-words: Brazilian savanna; water management; water conflicts. INTRODUCTION The Cerrado is the second largest Brazilian biome in extension, with about 204 million hectares, occupying 24% of the national territory approximately. Its largest portion is located within the Brazilian Central Plateau which consists of higher altitude areas in the central part of the country.