Queen Conch Fisheries and Their Management in the Caribbean

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

On the Half Shell Shellfish Caviar Service

ON ICE Cold CAVIAR PUFF* 1/8 OZ ..........................................8.00/EA On the Half Shell PADDLEFISH CAVIAR, CULTURED CREAM, POTATO, CHIVES WITH COCKTAIL SAUCE, SHALLOT SAUCE & LEMON SC YELLOW SQUASH ............................................... 10.00 DAILY OYSTER FIX* 1/2 DOZEN ............................... 17.00 LEMON VERJUS, HAZELNUT, CURED EGG YOLK WITH SMOKED DULSE CHIMICHURRI OCTOPUS ESCABECHE* .......................................... 15.00 TODAY’S FEATURES SALINITY SIZE PER CALABRIAN CHILIES, SQUID INK CHICHARRON, OLIVES AFTERNOON DELIGHTS, RI* MED MED 2.75 MARK’S RED SNAPPER CEVICHE* ............................. 14.00 LECHE DE TIGRE, CILANTRO OUTLAWS, FL* HIGH MED 3.00 SMOKED FISH DIP ................................................. 14.00 LOW CO. CUPS, SC* HIGH MED 3.00 EVERYTHING CRACKERS, CHIVES, ORANGE ZEST STONES BAY, NC* MED MED 2.75 ROYAL RED SHRIMP GAZPACHO ............................... 13.00 WELLFLEETS, MA* MED MED 3.00 BRIOCHE, CUCUMBER DUKES OF TOPSAIL, NC* HIGH MED 3.00 SEASONAL GREENS ................................................ 12.00 GREEN GODDESS, SC PEARS, PEANUTS LITTLENECK CLAMS,VA HIGH SM 1.25 ADD SHRIMP OR CRABMEAT +8.00 Shellfish NOt Cold WITH ACCOMPANIMENTS GRILLED OYSTERS ................................................ 20.00 BLUE CRAB CLAWS, NC 1/4 LB .................................. 12.00 UNI BUTTER, PERSILLADE, BLACK LIME MOJO SAUCE, ALEPPO SALTED FISH BEIGNETS .......................................... 14.00 * KOMBU POACHED LOBSTER, ME 1/2 LB ..................... 21.00 THYME, -

Environment for Development Improving Utilization of the Queen

Environment for Development Discussion Paper Series December 2020 ◼ EfD DP 20-39 Improving Utilization of the Queen Conch (Aliger Gigas) Resource in the Colombian Caribbean A Bioeconomic Model of Rotational Harvesting Jorge Marco, Diego Valderrama, Mario Rueda, and Maykol R o dr i g ue z - P r i et o Discussion papers are research materials circulated by their authors for purposes of information and discussion. They have not necessarily undergone formal peer review. Central America Chile China Research Program in Economics and Research Nucleus on Environmental and Environmental Economics Program in China Environment for Development in Central Natural Resource Economics (NENRE) (EEPC) America Tropical Agricultural Research and Universidad de Concepción Peking University Higher Education Center (CATIE) Colombia Ghana The Research Group on Environmental, Ethiopia The Environment and Natural Resource Natural Resource and Applied Economics Environment and Climate Research Center Research Unit, Institute of Statistical, Social Studies (REES-CEDE), Universidad de los (ECRC), Policy Studies Institute, Addis and Economic Research, University of Andes, Colombia Ababa, Ethiopia Ghana, Accra India Kenya Nigeria Centre for Research on the Economics of School of Economics Resource and Environmental Policy Climate, Food, Energy, and Environment, University of Nairobi Research Centre, University of Nigeria, (CECFEE), at Indian Statistical Institute, Nsukka New Delhi, India South Africa Tanzania Sweden Environmental Economics Policy Research Environment -

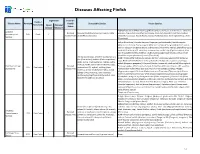

Diseases Affecting Finfish

Diseases Affecting Finfish Legislation Ireland's Exotic / Disease Name Acronym Health Susceptible Species Vector Species Non-Exotic Listed National Status Disease Measures Bighead carp (Aristichthys nobilis), goldfish (Carassius auratus), crucian carp (C. carassius), Epizootic Declared Rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss), redfin common carp and koi carp (Cyprinus carpio), silver carp (Hypophtalmichthys molitrix), Haematopoietic EHN Exotic * Disease-Free perch (Percha fluviatilis) Chub (Leuciscus spp), Roach (Rutilus rutilus), Rudd (Scardinius erythrophthalmus), tench Necrosis (Tinca tinca) Beluga (Huso huso), Danube sturgeon (Acipenser gueldenstaedtii), Sterlet sturgeon (Acipenser ruthenus), Starry sturgeon (Acipenser stellatus), Sturgeon (Acipenser sturio), Siberian Sturgeon (Acipenser Baerii), Bighead carp (Aristichthys nobilis), goldfish (Carassius auratus), Crucian carp (C. carassius), common carp and koi carp (Cyprinus carpio), silver carp (Hypophtalmichthys molitrix), Chub (Leuciscus spp), Roach (Rutilus rutilus), Rudd (Scardinius erythrophthalmus), tench (Tinca tinca) Herring (Cupea spp.), whitefish (Coregonus sp.), North African catfish (Clarias gariepinus), Northern pike (Esox lucius) Catfish (Ictalurus pike (Esox Lucius), haddock (Gadus aeglefinus), spp.), Black bullhead (Ameiurus melas), Channel catfish (Ictalurus punctatus), Pangas Pacific cod (G. macrocephalus), Atlantic cod (G. catfish (Pangasius pangasius), Pike perch (Sander lucioperca), Wels catfish (Silurus glanis) morhua), Pacific salmon (Onchorhynchus spp.), Viral -

Nautiloid Shell Morphology

MEMOIR 13 Nautiloid Shell Morphology By ROUSSEAU H. FLOWER STATEBUREAUOFMINESANDMINERALRESOURCES NEWMEXICOINSTITUTEOFMININGANDTECHNOLOGY CAMPUSSTATION SOCORRO, NEWMEXICO MEMOIR 13 Nautiloid Shell Morphology By ROUSSEAU H. FLOIVER 1964 STATEBUREAUOFMINESANDMINERALRESOURCES NEWMEXICOINSTITUTEOFMININGANDTECHNOLOGY CAMPUSSTATION SOCORRO, NEWMEXICO NEW MEXICO INSTITUTE OF MINING & TECHNOLOGY E. J. Workman, President STATE BUREAU OF MINES AND MINERAL RESOURCES Alvin J. Thompson, Director THE REGENTS MEMBERS EXOFFICIO THEHONORABLEJACKM.CAMPBELL ................................ Governor of New Mexico LEONARDDELAY() ................................................... Superintendent of Public Instruction APPOINTEDMEMBERS WILLIAM G. ABBOTT ................................ ................................ ............................... Hobbs EUGENE L. COULSON, M.D ................................................................. Socorro THOMASM.CRAMER ................................ ................................ ................... Carlsbad EVA M. LARRAZOLO (Mrs. Paul F.) ................................................. Albuquerque RICHARDM.ZIMMERLY ................................ ................................ ....... Socorro Published February 1 o, 1964 For Sale by the New Mexico Bureau of Mines & Mineral Resources Campus Station, Socorro, N. Mex.—Price $2.50 Contents Page ABSTRACT ....................................................................................................................................................... 1 INTRODUCTION -

Population and Reproductive Biology of the Channeled Whelk, Busycotypus Canaliculatus, in the US Mid-Atlantic

W&M ScholarWorks VIMS Articles 2017 Population and Reproductive Biology of the Channeled Whelk, Busycotypus canaliculatus, in the US Mid-Atlantic Robert A. Fisher Virginia Institute of Marine Science, [email protected] David Rudders Virginia Institute of Marine Science, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/vimsarticles Part of the Marine Biology Commons Recommended Citation Fisher, Robert A. and Rudders, David, "Population and Reproductive Biology of the Channeled Whelk, Busycotypus canaliculatus, in the US Mid-Atlantic" (2017). VIMS Articles. 304. https://scholarworks.wm.edu/vimsarticles/304 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in VIMS Articles by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Journal of Shellfish Research, Vol. 36, No. 2, 427–444, 2017. POPULATION AND REPRODUCTIVE BIOLOGY OF THE CHANNELED WHELK, BUSYCOTYPUS CANALICULATUS, IN THE US MID-ATLANTIC ROBERT A. FISHER* AND DAVID B. RUDDERS Virginia Institute of Marine Science, College of William and Mary, PO Box 1346, Gloucester Point, VA 23062 ABSTRACT Channeled whelks, Busycotypus canaliculatus, support commercial fisheries throughout their range along the US Atlantic seaboard. Given the modest amounts of published information available on channeled whelk, this study focuses on understanding the temporal and spatial variations in growth and reproductive biology in the Mid-Atlantic region. Channeled whelks were sampled from three inshore commercially harvested resource areas in the US Mid-Atlantic: Ocean City, MD (OC); Eastern Shore of Virginia (ES); and Virginia Beach, VA (VB). The largest whelk measured 230-mm shell length (SL) and was recorded from OC. -

Impact of the the COVID-19 Pandemic on a Queen Conch (Aliger Gigas) Fishery in the Bahamas

Impact of the the COVID-19 pandemic on a queen conch (Aliger gigas) fishery in The Bahamas Nicholas D. Higgs Cape Eleuthera Institute, Rock Sound, Eleuthera, Bahamas ABSTRACT The onset of the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic in early 2020 led to a dramatic rise in unemployment and fears about food-security throughout the Caribbean region. Subsistence fisheries were one of the few activities permitted during emergency lockdown in The Bahamas, leading many to turn to the sea for food. Detailed monitoring of a small-scale subsistence fishery for queen conch was undertaken during the implementation of coronavirus emergency control measures over a period of twelve weeks. Weekly landings data showed a surge in fishing during the first three weeks where landings were 3.4 times higher than subsequent weeks. Overall 90% of the catch was below the minimum legal-size threshold and individual yield declined by 22% during the lockdown period. This study highlights the role of small-scale fisheries as a `natural insurance' against socio-economic shocks and a source of resilience for small island communities at times of crisis. It also underscores the risks to food security and long- term sustainability of fishery stocks posed by overexploitation of natural resources. Subjects Aquaculture, Fisheries and Fish Science, Conservation Biology, Marine Biology, Coupled Natural and Human Systems, Natural Resource Management Keywords Fisheries, Coronavirus, COVID-19, IUU, SIDS, SDG14, Food security, Caribbean, Resiliance, Small-scale fisheries Submitted 2 December 2020 INTRODUCTION Accepted 16 July 2021 Published 3 August 2021 Subsistence fishing has played an integral role in sustaining island communities for Corresponding author thousands of years, especially small islands with limited terrestrial resources (Keegan et Nicholas D. -

Read All About Queen Conch on Bonaire

Adopt a Conch! Read all about Queen Conch on Bonaire • What is the Conch Restoration Project about? • The 8 stages in the lifecycle of the queen conch • Queen Conch: the facts of life • Strombus Gigas: science & research • How to contact involved organisations This presentation is donated by the Bon Kousa Foundation Bonaire | www.bonkousa.org Adopt a Conch! What is the Conch Restoration Project about? The Queen Conch is an endangered species on Bonaire. To protect the Queen Conch, taking conch became forbidden back in 1985. However, as the conch has been part of the local and regional cuisine for centuries, it is regretfully still rather common to poach the conch. As by the end of 2010 the number of mature conch have reached a critical small number the Conch Restoration Project was developed, which also involves the Bonairean fisherman and community, as a last resort to save the Queen Conch. By working side by side the project helps the Bonaireans realize that they are the custodians of their own resource. Bonaire needs to stops poaching today and thus give the Conch population time to recover so that in future, we all may be able to enjoy the conch again. The Conch Restoration Project consists of both an extensive awareness campaign for children and adults plus a scientific research program. A team of scientists is gathering information on the habitat and the Queen Conch stock. Last year an inventory has been made of conch in Lac Bay. All conch are tagged in order to identify and follow growth and migration or movements during the project. -

Sustainable Shellfishshellfish Recommendations for Responsible Aquaculture

SustainableSustainable ShellfishShellfish Recommendations for responsible aquaculture By Heather Deal, M.Sc. As Sustainable Shellfish went to press, the B.C. Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Fisheries (MAFF) pulled their draft Code of Practice for Shellfish Aquaculture from circulation. This document, upon which much of Sustainable Shellfish is based, was one component in guiding, monitoring, and reg- ulating B.C.’s rapidly growing shellfish industry. The Code was by no means exhaustive – Sustainable Shellfish aims to address its gaps and limitations, including its lack of con- sideration for stringent environmental safeguards on the expanding industry. Now that the Code of Practice has been abandoned by gov- ernment, the shellfish industry is managed via complaints to the Farm Industry Review Board. This board uses "normal farm practices" as a standard, but does not and, according to MAFF, will not define what "normal farm practices" are with regard to aquaculture. In other words, although there is leg- islation in place, there are no longer governmental stan- dards or guidelines specific to this industry. The BC Shellfish Growers Association (BCSGA) does have an Environmental Management System and Code of Practice, which is very similar to that which MAFF pro- duced. The BCSGA Code is not available on their website, so please contact the association directly to request a copy: #7 - 140 Wallace Street Nanaimo, BC V9R 5B1 Tel: (250) 714-0804 Fax: (250) 714-0805 Email: [email protected] The draft government Code of Practice is still available on the David Suzuki Foundation website, www.davidsuzuki.org/oceans. Sustainable Shellfish, used in conjunction with the non- operational Code offers a way forward towards a low impact industry with minimal harmful effects on B.C.’s marine environment and coastal communities. -

Opinion Why Do Fish School?

Current Zoology 58 (1): 116128, 2012 Opinion Why do fish school? Matz LARSSON1, 2* 1 The Cardiology Clinic, Örebro University Hospital, SE -701 85 Örebro, Sweden 2 The Institute of Environmental Medicine, Karolinska Institute, SE-171 77 Stockholm, Sweden Abstract Synchronized movements (schooling) emit complex and overlapping sound and pressure curves that might confuse the inner ear and lateral line organ (LLO) of a predator. Moreover, prey-fish moving close to each other may blur the elec- tro-sensory perception of predators. The aim of this review is to explore mechanisms associated with synchronous swimming that may have contributed to increased adaptation and as a consequence may have influenced the evolution of schooling. The evolu- tionary development of the inner ear and the LLO increased the capacity to detect potential prey, possibly leading to an increased potential for cannibalism in the shoal, but also helped small fish to avoid joining larger fish, resulting in size homogeneity and, accordingly, an increased capacity for moving in synchrony. Water-movements and incidental sound produced as by-product of locomotion (ISOL) may provide fish with potentially useful information during swimming, such as neighbour body-size, speed, and location. When many fish move close to one another ISOL will be energetic and complex. Quiet intervals will be few. Fish moving in synchrony will have the capacity to discontinue movements simultaneously, providing relatively quiet intervals to al- low the reception of potentially critical environmental signals. Besides, synchronized movements may facilitate auditory grouping of ISOL. Turning preference bias, well-functioning sense organs, good health, and skillful motor performance might be important to achieving an appropriate distance to school neighbors and aid the individual fish in reducing time spent in the comparatively less safe school periphery. -

Shells Shells Are the Remains of a Group of Animals Called Molluscs

Inspire - Educate – Showcase Shells Shells are the remains of a group of animals called molluscs. Bivalves Molluscs are soft-bodied animals inhabiting marine, land and Bivalves are molluscs made up of two shells joined by a hinge with freshwater habitats. The shells we commonly come across on the interlocking teeth. The shells are usually held together by a tough beach belong to one of two groups of molluscs, either gastropods ligament. These creatures also have a set of two tubes which which have one shell, or bivalves which have two shells. The material sometimes stick out from shell allowing the animal to breathe and making up the shell is secreted by special glands of the animal living feed. within it. Some commonly known bivalves include clams, cockles, mussels, scallops and oysters. Can you think of any others? Oysters and mussels attach themselves to solid objects such as jetty pylons or rocks on the sea floor and filter feed by taking Gastropod = One Shell Bivalve = Two Shells water into one tube and removing the tiny particles of plankton from the water. In contrast, scallops and cockles are moving Particular shell shapes have been adapted to suit the habitat and bivalves and can either swim through the conditions in which the animals live, helping them to survive. The water or pull themselves through the sand wedge shape of a cockle shell allows them to easily burrow into the with their muscular, soft bodies. sand. Ribs, folds and frills on many molluscs help to strengthen the shell and provide extra protection from predators. -

Size at Maturation, Spawning Variability and Fecundity in the Queen Conch, Aliger Gigas

Gulf and Caribbean Research Volume 31 Issue 1 2020 Size at Maturation, Spawning Variability and Fecundity in the Queen Conch, Aliger gigas Richard S. Appeldoorn GCFIMembers, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://aquila.usm.edu/gcr Part of the Marine Biology Commons, and the Population Biology Commons To access the supplemental data associated with this article, CLICK HERE. Recommended Citation Appeldoorn, R. S. 2020. Size at Maturation, Spawning Variability and Fecundity in the Queen Conch, Aliger gigas. Gulf and Caribbean Research 31 (1): GCFI 10-GCFI 19. Retrieved from https://aquila.usm.edu/gcr/vol31/iss1/11 DOI: https://doi.org/10.18785/gcr.3101.11 This Gulf and Caribbean Fisheries Institute Partnership is brought to you for free and open access by The Aquila Digital Community. It has been accepted for inclusion in Gulf and Caribbean Research by an authorized editor of The Aquila Digital Community. For more information, please contact [email protected]. VOLUME 25 VOLUME GULF AND CARIBBEAN Volume 25 RESEARCH March 2013 TABLE OF CONTENTS GULF AND CARIBBEAN SAND BOTTOM MICROALGAL PRODUCTION AND BENTHIC NUTRIENT FLUXES ON THE NORTHEASTERN GULF OF MEXICO NEARSHORE SHELF RESEARCH Jeffrey G. Allison, M. E. Wagner, M. McAllister, A. K. J. Ren, and R. A. Snyder....................................................................................1—8 WHAT IS KNOWN ABOUT SPECIES RICHNESS AND DISTRIBUTION ON THE OUTER—SHELF SOUTH TEXAS BANKS? Harriet L. Nash, Sharon J. Furiness, and John W. Tunnell, Jr. ......................................................................................................... 9—18 Volume 31 ASSESSMENT OF SEAGRASS FLORAL COMMUNITY STRUCTURE FROM TWO CARIBBEAN MARINE PROTECTED 2020 AREAS ISSN: 2572-1410 Paul A. -

ICES Marine Science Symposia

ICES mar. Sei. Symp., 199: 13-18. 1995 Potential depensatory mechanisms operating on reproductive output in gonochoristic molluscs, with particular reference to strombid gastropods Richard S. Appeldoorn Appeldoom, R. S. 1995. Potential depensatory mechanisms operating on repro ductive output in gonochoristic molluscs, with particular reference to strombid gastro pods. - ICES mar. Sei. Symp., 199: 13-18. Molluscs are typically sessile or slow moving, yet successful reproduction requires close proximity to potential mates. Three mechanisms are identified whereby repro ductive potential of a population can be limited under conditions of low density. The first is the reduction in numbers of spawners as abundance decreases. The second reflects the difficulty in finding mates, and takes the form of either (1) search time for slow but motile species, or (2) wasted spawning (or non-spawning) for sessile species, where gametes are not fertilized. The third mechanism is a breakdown of a positive feedback loop between contact with males (either direct or through chemical cues) and rate of gametogenesis and spawning in females, i.e., sexual facilitation. The second and third mechanisms are functions of local density, rather than overall abundance. Literature review and present studies on strombid gastropods indicate the potential for these mechanisms to occur. Many species are characterized by behaviours, such as aggregative settlement, that serve to overcome this problem. Intensive fishing prac tices may invoke these depensatory mechanisms as local density and abundance are reduced, thereby increasing the chance of recruitment failure. Richard S. Appeldoom: Department of Marine Sciences, University of Puerto Rico, Mayagiiez, Puerto Rico 00681-5000 [tel: (+809) 899 2048, fax: (+809) 899 5500], Introduction dation, cannibalism, competition, and starvation) occurring during early life stages.