On Editing the Avesta

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The University of Chicago Oriental Institute Seminars Number 2

oi.uchicago.edu i THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO ORIENTAL INSTITUTE SEMINARS NUMBER 2 Series Editors Leslie Schramer and Thomas G. Urban oi.uchicago.edu ii oi.uchicago.edu iii MARGINS OF WRITING, ORIGINS OF CULTURES edited by SETH L. SANDERS with contributions by Seth L. Sanders, John Kelly, Gonzalo Rubio, Jacco Dieleman, Jerrold Cooper, Christopher Woods, Annick Payne, William Schniedewind, Michael Silverstein, Piotr Michalowski, Paul-Alain Beaulieu, Theo van den Hout, Paul Zimansky, Sheldon Pollock, and Peter Machinist THE ORIENTAL INSTITUTE OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO ORIENTAL INSTITUTE SEMINARS • NUMBER 2 CHICAGO • ILLINOIS oi.uchicago.edu iv Library of Congress Control Number: 2005938897 ISBN: 1-885923-39-2 ©2006 by The University of Chicago. All rights reserved. Published 2006. Printed in the United States of America. The Oriental Institute, Chicago Co-managing Editors Thomas A. Holland and Thomas G. Urban Series Editors’ Acknowledgments The assistance of Katie L. Johnson is acknowledged in the production of this volume. Front Cover Illustration A teacher holding class in a village on the Island of Argo, Sudan. January 1907. Photograph by James Henry Breasted. Oriental Institute photograph P B924 Printed by McNaughton & Gunn, Saline, Michigan The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Infor- mation Services — Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1984. oi.uchicago.edu v TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ................................................................................................................. -

Parsi Adoptions

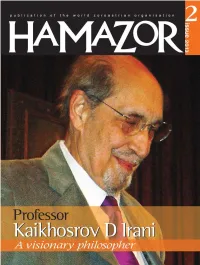

15 April 2013 Hamazor’s Future – Transition from Print to Digital Dear Member, This is a bittersweet moment in Hamazor’s immensely proud history. The members of WZO’s Managing Committee have consulted widely and debated this issue passionately. The free publication will go all-digital in 2015. The fourth issue of Hamazor in 2014 will be its last as a free print magazine. Bittersweet, we say. Bitter, because we’d be lying if we didn’t confess to a bruised and heavy heart. Like all people, we love print: always have, always will do. Sweet, because we are rising spiritedly to a challenge, not wringing our hands in impotent despair over the way modern life — and modern reading habits — will increasingly render our print edition unviable. In our judgment, we have reached a tipping point at which we can most efficiently and effectively reach our readers in all-digital format. This was not the case just two years ago. It will increasingly be the case in the years ahead. This decision is not about the quality of the brand or the writing - that is as powerful as ever. It is about the challenging economics of print publishing and distribution. Hamazor is produced by our executive editor Toxy Cowasjee, who has been offering an excellent production consistently since 2002. We will continue to build on Hamazor’s success and ensure your, its readers’ engagement. Exiting print is an extremely difficult moment for all of us who love the romance of print and the unique experience of producing, receiving and reading it. -

Jaina Studies

Jaina Studies NEWSLETTER OF THE CENTRE OF JAINA STUDIES March 2015 Issue 10 CoJS Newsletter • March 2015 • Issue 10 Centre of Jaina Studies Members SOAS MEMBERS Honorary President Professor Christine Chojnacki Dr Andrea Luithle-Hardenberg (University of Lyon) (University of Tübingen) Chair/Director of the Centre Dr Anne Clavel Professor Adelheid Mette Dr Peter Flügel (Aix en Province) (University of Munich) Dr Crispin Branfoot Professor John E. Cort Gerd Mevissen Department of the History of Art (Denison University) (Berliner Indologische Studien) and Archaeology Dr Eva De Clercq Professor Anne E. Monius Professor Rachel Dwyer (University of Ghent) (Harvard Divinity School) South Asia Department Dr Robert J. Del Bontà Professor Hampa P. Nagarajaiah (Independent Scholar) (University of Bangalore) Department of the Study of Religions Dr Saryu V. Doshi Professor Thomas Oberlies Dr Erica Hunter (Mumbai) (University of Göttingen) Department of the Study of Religions Professor M.A. Dhaky Dr Leslie Orr Dr James Mallinson (Ame rican Institute of Indian Studies, Gurgaon) (Concordia University, Montreal) South Asia Department Professor Christoph Emmrich Dr Jean-Pierre Osier Professor Werner Menski (University of Toronto) (Paris) School of Law Dr Anna Aurelia Esposito Dr Lisa Nadine Owen Professor Francesca Orsini (University of Würzburg) (University of North Texas) South Asia Department Janet Leigh Foster Professor Olle Qvarnström Dr Ulrich Pagel (SOAS Alumna) (University of Lund) Department of the Study of Religions Dr Lynn Foulston Dr Pratapaditya -

Psychologischer Club Zürich Author Catalogue Page 1 ABE 25.08.20

Psychologischer Club Zürich Author catalogue Page 1 ABE 25.08.20 Abegg, Carl Julius. - Therese Von Lisieux : Aufschrei einer Seele / Carl Julius Abegg B 620 a München : Passavia, 1956 (812) Abegg, Emil. - Die Indiensammlung der Universität Zürich / Emil Abegg B 190 Zürich : Beer & Cie., 1935 (807) Abegg, Emil. - Indische Psychologie / Emil Abegg B 192 Zürich : Rascher, 1945 (808) Abegg, Emil. - Der Messiasglaube in Indien und Iran / Auf Grund der Quellen dargestellt B 191 von Emil Abegg Berlin; Leipzig : de Gruyter, 1928 (809) Abegg, Emil. - Der Pretakalpa des Garuda-Purana (Naunidhirama's Saroddhara): Eine B 193 Darstellung des hinduistischen Totenkultes und Jenseitsglaubens: Aus dem Sanskrit übers. und erklärt und mit Indices versehen v. Emil Abegg / Emil Abbeg Berlin : de Gruyter, 1921 (810) Abegg, Emil. - Der Pretakalpa des Garuda-Purana (Naunidhirama's Saroddhara): Eine B 193 a Darstellung des hinduistischen Totenkultes und Jenseitsglaubens: Aus dem Sanskrit übers. und erklärt und mit Indices versehen v. Emil Abegg / Emil Abbeg Berlin : de Gruyter, 1956 (811) Abel, Othenio. - Die vorweltlichen Tiere in Märchen, Sage und Aberglauben / Othenio Abel B 1513 Karlsruhe i. Br. : Braunsche Hofbuchdruckerei und Verlag, 1923 (832) Abell, Arthur M. - Gespräche mit berühmten Komponisten : So entstanden ihre unsterblichen B 1461 Meisterwerke / Arthur M. Abell [Aus dem Englischen über. von Christian Dehm. Orig. Titel : Talks with great Composers] Garmisch-Partenkirchen : Schroeder Verlag, 1962 (833) Adams, Gordon. - Was Niemand glauben will : Abenteuer im Reich der Parapsychologie / B 1024 Peter Andreas und Gordon Adams Berlin, u.a. : Ullstein, 1967 (891) Adamson, Joy. - Born Free: A Lioness of Two Worlds / Joy Adamson, with extracts from B 1365 b George Adamson's letters and a preface from William Percy and a foreword by Charles Pitman London : Collins & Harvill, 1960 (935) Adlington, William. -

GRETIL E-Library Karl Friedrich Geldner Jürgen Hanneder (Online-Version Oktober 2014)1

FILE Name: Han014__Hanneder_Karl_Friedrich_Geldner.pdf PURL: http://resolver.sub.uni-goettingen.de/purl/?gr_elib-274 Type: searchable PDF Encoding: Unicode (ā ī ū ṛ ṝ ḷ ḹ ṅ ñ ṭ ḍ ṇ ś ṣ ḥ ṃ ...) Date: 23.9.2014 BRIEF RECORD Author: Hanneder, Jürgen Title: Karl Friedrich Geldner Publ.: Online version, October 2014 Description: 9 p. FULL RECORD http://gretil.sub.uni-goettingen.de/gr_elib.htm NOTICE This file may be copied on the condition that its entire contents, including this data sheet, remain intact. GRETIL e-library Karl Friedrich Geldner Jürgen Hanneder (online-Version Oktober 2014)1 Geldners Leben und Wirken wurde in Nachrufen aus der Feder von akademischen Weggefährten recht prägnant dargestellt2 und es gab daher zunächst keine Möglich- keit, über diese Informationen aus erster Hand hinauszugelangen. Erst durch die Erschließung neuer Quellen in verschiedenen indologischen Nachlässen3 konnte die- ses Bild noch einmal ergänzt werden.4 Die folgende kurze Biographie Geldners soll vor allem dieser neuen Quellenlage Rechnung tragen. Karl Friedrich Eugen Geldner wurde am 17.12.1852 in Saalfeld als Sohn von Christian Friedrich Georg Geldner (1821–1890) geboren,5 welcher in Hildburghausen, später in Meiningen in verschiedenen kirchlichen Ämtern wirkte. Karl Geldner studierte wie der Vater in Leipzig, allerdings nicht Theologie, sondern Sanskrit und Avestisch bei Brockhaus und Windisch. Doch für aufstrebende Vedisten dieser Generation war der beste Studienort Tübingen, da man dort von Rudolph von Roth, der Koryphäe der sich erst entwickelnden vedischen Studien und dem verantwortlichen Veda-Spezialisten am sogenannten Petersburger Wörterbuch,6 den Fortschritt des Faches aus erster Hand erfahren konnte. Geldner meldete sich im Sommer 1872 bei Roth brieflich an und dieser antwortete am 10.6.1872,7 daß Geldner und sein Freund ihm »ganz willkommen sein« und er ihm gerne bei der »Wahl der Wohnungen« behilflich sein werde. -

Download Here

References A2 Technologies , <http://www.a2technologies.com/exoscan_handheld.html>, cached copy 2011; see <http://www.chem.agilent.com/en- US/products-services/Instruments-Systems/Molecular-Spectroscopy/4100-ExoScan-Series-FTIR-(handheld)/Pages/default.aspx>, last access November 2014. d’Abbadie, Antoine (1859), Catalogue raisonné de manuscrits éthiopiens appartenant à Antoine d’Abbadie , Paris: Imprimerie Impériale. Fihris ma ḫṭūṭā t maktabat Mamm ā) ! س طت رة طت وا ,(ʿAbd al-Qādir Mamm ā Ḥaydara – Ayman Fu ʾād Sayyid (2000–2003 Ḥaydara li-ʾl-ma ḫṭūṭā t wa-ʾl-wa ṯāʾiq, ‘Catalogue of Manuscripts in Mamma Haidara Library – Mali’), I–IV , London: Al-Furq n (Silsilat Fah ris al-ma "#$# t al-Isl miyya / Handlists of Islamic Manuscripts 34-36, 46). Abełyan, Manuk (1941), Կորյուն , Վարք Մաշտոցի (Koryun , Vark ʿ Maštoc ʿi, ‘Koriun, The Life of Maštoc ’), Erevan: Haypethrat. .Al-Sīra al-Hil ālīya , ‘The deeds of the [Banu] Hilal’), Al-Qhira: A "br al-yawm) ا)ة ا ' ,(al-Abn $d%, Abd ar-Ra &mn (1988 Abrahamyan, Ašot G. (1947), Հայկական պալեոգրաֆիա (Haykakan paleografia , ‘Armenian Paleography’), Erevan: Aredit. Abrahamyan, Ašot G. (1973), Հայոց գիր եւ գրչություն (Hayoc ʿ gir ew gr čʿut ʿyun , ‘The Letters and Writing of the Armenians’), Erevan. Abramišvili, Guram (1976), ‘ატენის სიონის უცნობი წარწერები ’ (Aṭenis Sionis ucnobi c arc̣ erebị , ‘Unknown inscriptions from the Sioni of A#eni’), Macne. Is ṭoriisa da arkeologiis seria , 2 , 170–176 . Abramišvili, Guram – Zaza Aleksi )e (1978), ‘მხედრული დამწერლობის სათავეებთან ’ (Mxedruli damc erlobiṣ sataveebtan , ‘At the origins of the mxedruli script’), Cis ḳari , 5 , 134–144; 6 , 128–137 . Abrams, Daniel (2012), Kabbalistic Manuscripts and Textual Theory : Methodologies of Textual Scholarship and Editorial Practice in the Study of Jewish Mysticism , Jerusalem: The Hebrew University Magnes Press (Sources and Studies in the Literature of Jewish Mysticism). -

1 Vedic Bibliography General Introductions: FORTSON, Benjamin

INTRODUCTION TO VEDIC – LENT TERM 2014 (MJCS) Vedic Bibliography General Introductions: FORTSON, Benjamin W. (IV). 2010. “Indo-Iranian I: Indic” in Indo-European Language and Culture: An Introduction (Second Edition), 202-226. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell. (Cf. also “Indo-Iranian II: Iranian” pp.227-247) JAMISON, Stephanie W. 2004. “Sanskrit”. The Cambridge Encyclopedia of the World's Ancient Languages, ed. by R.D. WOODARD, 673-716. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. LAZZERONI, Romano. 1998. “Sanskrit”. The Indo-European Languages, ed. by A.G. RAMAT & P. RAMAT, 98-124. London & New York: Routledge. Dictionaries: *BÖHTLINGK, Otto & Rudolph ROTH. 1855-1875. Sanskrit-Wörterbuch (7 Vols.). St. Petersburg: Buchdr. der K. Akademie der Wissenschaften. (Known as the Petersburger Wörterbuch, and stands as the fundamental basis for all modern Sanskrit dictionaries. Online version searchable on the Universität zu Köln website: http://www.sanskrit-lexicon.uni-koeln.de/scans/PWGScan/disp2/index.php) *GRAßMANN, Hermann. 1873-1875. Wörterbuch zum Rig-Veda. Leipzig: F. A. Brockhaus. (Exhaustive. Unaltered reprints since the 3rd ed. (1955) by Harrassowitz Verlag in th Wiesbaden. The 6 edition of 1996 has been revised by Maria KOZIANKA, taking into account our improved understanding of the Vedic text, however the text of the dictionary has not been re-set.) LUBOTSKY, Alexander. 1997. A R̥gvedic Word Concordance. New Haven: American Oriental Society. (A new computer-prepared concordance based on NOOTEN and HOLLAND’s new metrically restored text.) MACDONELL, Anthony Arthur. 1924. A Practical Sanskrit Dictionary: With Transliteration, Accentuation, and Etymological Analysis Throughout. London: Oxford University Press. (A good hand-dictionary, but largely obsolete because of the online Cologne dictionaries.) MAYRHOFER, Manfred. -

Panels NINTH EUROPEAN CONFERENCE of IRANIAN STUDIES (ECIS 9) Berlin, 9–13 September 2019 Institute of Iranian Studies, Freie Universität Berlin

Abstracts of Panels NINTH EUROPEAN CONFERENCE OF IRANIAN STUDIES (ECIS 9) Berlin, 9–13 September 2019 Institute of Iranian Studies, Freie Universität Berlin Layout and design: Shervin Farridnejad © 2019 The Peacock motif is taken from Maġsūd-Beyk Mosque, Esfahan, Safavid Period (From: Nasr-Esfahani, Gholamreza, 2006, The Design of the Peacock on the Mosaic Tiles of Esfahan, Esfahan). Special thanks to Albrecht Flachowsky Institute of Iranian Studies Freie Universität Berlin Fabeckstr. 23-25 14195 Berlin Ninth European Conference of Iranian Studies (ECIS 9) Berlin, 9–13 September 2019 Institute of Iranian Studies, Freie Universität Berlin Scientific Committee (The board of the Societas Iranologica Europaea) • Pierfrancesco Callieri (President of SIE / University of Bologna) • Gabrielle van den Berg (Vice President / Leiden University) • Florian Schwarz (Secretary / Institute of Iranian Studies, Austrian Academy of Sciences, Vienna) • Mohammad Ali Amir-Moezzi (École Pratique des Hautes Études, Paris) • Desmond Durkin-Meisterernst (Berlin-Brandenburgische Akademie der Wissenschaften / FU Berlin) • Pavel Borisovich Lurje (State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg) • Nicholas Sims-Williams (SOAS, University of London) • Christoph U. Werner (Philipps-Universität Marburg) • Maria Carmela Benvenuto (Treasurer / University of Rome “La Sapienza”) Conveners (Institute of Iranian Studies, Freie Universität Berlin) • Alberto Cantera • Shervin Farridnejad • Götz König • Khanna Omarkhali • Arash Zeini Conference Student Assistants • Mahnaz Ghasemi Kadijani -

Newsletter Spring Final.Indd

CENTER FOR IRANIAN STUDIES NEWSLETTER Vol. 17, No. 1 SIPA-Columbia University-New York Spring 2005 NCYCLOPAEDIA RANICA NLINE KHOSROW SEMNANI E I O ELECTED CHAIRMAN OF THE OARD OF RUSTEES A DRASTIC NEW APPROACH B T The Encyclopaedia Iranica we reach entries such as MITHRA, has adopted a radically new ap- NOWRUZ, THE SASANIANS, THE SA- proach which affects the pace and FAVIDS, THE SHAH-NAMA, SHIʼISM, progress of the Encyclopaedia and or ZOROASTER. the time needed for its completion. In fact the Encyclopaedia is The new approach, which has been becoming a living institution which made possible by taking advantage of can be consulted by all and sundry, the advances in information technol- by scholars and students, to gain the ogy, makes the Encyclopaedia in fact latest information about Iranian lands a permanent database for accurate and and their varied relations with their reliable information about all aspects of neighbors and others. Now the great Iranian history and culture which is con- bulk of the entries that we invite and Following Mr. Mahmoud Khay- tinually updated and enriched by data receive belong to this category. The amiʼs departure as Chairman of the derived from archeological discoveries, printed version also continues as before Board, his nominee, Mr. Khosrow B. new publications, and events. and when we reach a new letter of the Semnani, a Vice-Chairman of the Board The Encyclopaedia Iranica is no alphabet we commit the articles that of the Encyclopaedia Iranica Founda- longer a mere series of published vol- have been published on our web site, tion, was elected by ballot in April 2005 umes which follows the alphabetical or- www.iranica.com, to print. -

FEZANA JOURNAL PASSING the BATON to the NEXT GENERATION Is Sponsored By

With Best Compliments From The Incorportated Trustees Of the Zoroastrian Charity Funds of Hong Kong, Canton & Macao FEZANAJOURNAL www.fezana.org Vol 32 No 2 Summer / Tabestan 1387 AY 3756 Z PUBLICATION OF THE FEDERATION OF ZOROASTRIAN ASSOCIATIONS OF NORTH AMERICA - CONTENT- Editor in Chief Dolly Dastoor, editor(@)fezana.org 02 Editorial Dolly Graphic & Layout Shahrokh Khanizadeh, www.khanizadeh.info Dastoor Technical Assistant Coomie Gazdar Consultant Editor Lylah M. Alphonse, lmalphonse(@)gmail.com 03 Message from the President Language Editor Douglas Lange ; Deenaz Coachbuilder Cover Design Feroza Fitch, ffitch(@)lexicongraphics.com 04 FEZANA update Publications Chair Behram Pastakia, bpastakia(@)aol.com Marketing Manager Nawaz Merchant [email protected] World Zarthushti Shazneen Rabadi Gandhi rabadis(@)gmail.com Community Awards Columnists Teenaz Javat: teenazjavat(@)hotmail.com Page 10 MahrukhMotafram: mahrukhm83(@)gmail.com Copy Editors Vahishta Canteenwalla Yasmin Pavri Nazneen Khumbatta Subscription Managers Arnavaz Sethna: ahsethna(@)yahoo.com Kershaw Khumbatta: Arnavaz Sethna(@)yahoo.com 20 Passing the Tir – Amordad- Shehrever 1387 AY (Fasli) Behman –Spendarmad 1387 AY, Fravardin 1388 AY (Shahenshahi) Baton to the Spendarmad 1387 AY, Fravardin Ardibehesht 1388 AY (kadimi) next generation 60 Return to Roots 66 In the News Cover design: Feroza Fitch of Lexicongraphics 76 Personal Profile 78 Milestones 81 Obituary Opinions expressed in the FEZANA Journal do not necessarily reflect the views of FEZANA or members of the editorial board. All submissions to the FEZANA JOURNAL become the 85 Books and Arts property of the publication and may be reproduced in any form. 91 List of Associations Published at Regal Press, Mississauga, Ontario, Canada FEZANA Journal Vol 32, No 2 ISSN 1068-2376 WINTER 2018 (USPS 021-495) published quarterly by FEZANA 8615 Meadowbrook Dr., Burr PARADIGM SHIFT IN Ridge, IL 60527. -

Abstracts NINTH EUROPEAN CONFERENCE of IRANIAN STUDIES (ECIS 9) Berlin, 9–13 September 2019 Institute of Iranian Studies, Freie Universität Berlin

Abstracts NINTH EUROPEAN CONFERENCE OF IRANIAN STUDIES (ECIS 9) Berlin, 9–13 September 2019 Institute of Iranian Studies, Freie Universität Berlin Layout and design: Shervin Farridnejad © 2019 The Peacock motif is taken from Maġsūd-Beyk Mosque, Esfahan, Safavid Period (From: Nasr-Esfahani, Gholamreza, 2006, The Design of the Peacock on the Mosaic Tiles of Esfahan, Esfahan). Special thanks to Albrecht Flachowsky Institute of Iranian Studies Freie Universität Berlin Fabeckstr. 23-25 14195 Berlin Ninth European Conference of Iranian Studies (ECIS 9) Berlin, 9–13 September 2019 Institute of Iranian Studies, Freie Universität Berlin Scientific Committee (The board of the Societas Iranologica Europaea) • Pierfrancesco Callieri (President of SIE / University of Bologna) • Gabrielle van den Berg (Vice President / Leiden University) • Florian Schwarz (Secretary / Institute of Iranian Studies, Austrian Academy of Sciences, Vienna) • Mohammad Ali Amir-Moezzi (École Pratique des Hautes Études, Paris) • Desmond Durkin-Meisterernst (Berlin-Brandenburgische Akademie der Wissenschaften / FU Berlin) • Pavel Borisovich Lurje (State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg) • Nicholas Sims-Williams (SOAS, University of London) • Christoph U. Werner (Philipps-Universität Marburg) • Maria Carmela Benvenuto (Treasurer / University of Rome “La Sapienza”) Conveners (Institute of Iranian Studies, Freie Universität Berlin) • Alberto Cantera • Shervin Farridnejad • Götz König • Khanna Omarkhali • Arash Zeini Conference Student Assistants • Mahnaz Ghasemi Kadijani • Kian Kahrom Contact and Venue E-Mail: [email protected] Conference venue: Institute of Iranian Studies, Fabeckstr. 23-25, 14195 Berlin/Germany HOSSEIN ABADIAN The Social Consequences of Rural Migrations to Tehran (1973-1979) This article concerns with the consequences of migrations to Tehran after the oil shock of 1973 and the role did play this issue in the upcoming circumstances of Iran. -

I V Visionary Experience of Mantra : an Ethnography in Andhra-Telangana

Visionary Experience of Mantra : An Ethnography in Andhra-Telangana by Alivelu Nagamani Graduate Department of Religion Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Leela Prasad, Supervisor ___________________________ David Morgan ___________________________ Hwansoo Kim ___________________________ Velcheru Narayana Rao Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate Department of Religion in the Graduate School of Duke University 2016 i v ABSTRACT Visionary Experience of Mantra : An Ethnography in Andhra-Telangana by Alivelu Nagamani Graduate Department of Religion Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Leela Prasad, Supervisor ___________________________ David Morgan ___________________________ Hwansoo Kim ___________________________ Velcheru Narayana Rao An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate Department of Religion in the Graduate School of Duke University 2016 Copyright by Alivelu Nagamani 2016 Abstract The use of codified sacred utterances, formulas or hymns called “mantras” is widespread in India. By and large, scholarship over the last few decades studies and explains mantras by resorting to Indian sources from over a millennium ago, and by applying such frameworks especially related to language as speech-act theory, semiotics, structuralism, etc. This research aims to understand