In the Matter of the Arbitration Between the MANAGEMENT

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Operator Profile 2002 - 2003

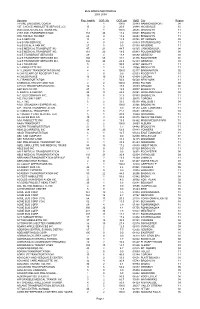

BUS OPERATOR PROFILE 2002 - 2003 Operator .Insp 02-03 .OOS 02-03 OOS Rate 02-03 OpID City Region 112 LIMOUSINE INC. 2 0 0.0 28900 CENTER MORICHES 10 1ST. CHOICE AMBULETTE SERVICE LCC 1 0 0.0 29994 HICKSVILLE 10 2000 ADVENTURES & TOURS INC 5 2 40.0 26685 BROOKLYN 11 217 TRANSPORTATION INC 5 1 20.0 24555 STATEN ISLAND 11 21ST AVE. TRANSPORTATION 201 30 14.9 03531 BROOKLYN 11 3RD AVENUE TRANSIT 57 4 7.0 06043 BROOKLYN 11 A & A ROYAL BUS COACH CORP. 1 1 100.0 30552 MAMARONECK 08 A & A SERVICE 17 3 17.6 05758 MT. VERNON 08 A & B VAN SERVICE 4 1 25.0 03479 STATEN ISLAND 11 A & B'S DIAL A VAN INC. 23 1 4.3 03339 ROCKAWAY BEACH 11 A & E MEDICAL TRANSPORT INC 60 16 26.7 06165 CANANDAIGUA 04 A & E MEDICAL TRANSPORT INC. 139 29 20.9 05943 POUGHKEEPSIE 08 A & E TRANSPORT 4 0 0.0 05508 WATERTOWN 03 A & E TRANSPORT SERVICES 39 1 2.6 06692 OSWEGO 03 A & E TRANSPORT SERVICES INC 154 25 16.2 24376 ROCHESTER 04 A & E TRANSPORT SERVICES INC. 191 35 18.3 02303 OSWEGO 03 A 1 AMBULETTE INC 9 0 0.0 20066 BROOKLYN 11 A 1 LUXURY TRANSPORTATION INC. 4 2 50.0 02117 BINGHAMTON 02 A CHILDCARE OF ROOSEVELT INC. 5 1 20.0 03533 ROOSEVELT 10 A CHILD'S GARDEN DAY CARE 1 0 0.0 04307 ROCHESTER 04 A CHILDS PLACE 12 7 58.3 03454 CORONA 11 A J TRANSPORTATION 2 1 50.0 04500 NEW YORK 11 A MEDICAL ESCORT AND TAXI 2 2 100.0 28844 FULTON 03 A&J TROUS INC. -

FINAL REPORT Ridership Enhancement Quick Study

FINAL REPORT Ridership Enhancement Quick Study Prepared by: Mineta Transportation Institute 210 N. 4th St, 4th Floor San Jose, CA 95112 Prepared for: Federal Transit Administration Office of Budget and Policy U.S. Department of Transportation September 29, 2005 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 4 Literature Review 4 Methodology 4 Findings 5 Recommendations 6 INTRODUCTION AND SCOPE 7 Overview of Research Approach 7 LITERATURE REVIEW 9 Adoption of Technology Innovation in Organizations 10 Innovation in Transit Agencies: Adoption of New Fare Programs and Operational Enhancements 11 Fare programs: transit pass and on-line sales programs 11 Operational enhancements: Guaranteed Ride Home programs 12 Smart card adoption and implications for other fare programs 13 Organizational mission and priorities 13 Agency patronage and markets 14 Agency risk-taking: uncertainty over the future of information technology 14 Effectiveness of public-private partnerships 15 Institutional arrangements and leadership 15 Organizational capacity to evaluate costs and benefits 16 Implications for the adoption of ridership enhancement techniques 17 Implications for study of enhancement techniques 18 SUMMARY OF FINDINGS 20 Factors associated with adoption of Eco/Employer Passes: 21 Factors associated with adoption of Day Passes 24 Factors associated with adoption of Guaranteed Ride Home programs 25 Factors associated with adaptation of On-line Fare Media sales 27 2 RECOMMENDATIONS 28 Eco/Employer Passes 29 Day Passes 30 Guaranteed Ride Home 31 On-Line Sales 32 REFERENCES -

Public Transit in NY, the Metropolitan Transportation Authority: Its Future and History Carrigy

Hofstra University, Department of Global Studies & Geography, Honors Essay Public Transit in New York The Past and Future of the Metropolitan Transportation Authority Michael Carrigy Fall 2010 Supervised by Dr. Jean-Paul Rodrigue Table of Contents Introduction: Public Transportation in the United States 3 New York’s MTA and Its Subsidiaries 7 MTA’s Departmental Structure 11 The MTA’s Report Card 19 Planning for the Future 26 Appendix 30 Bibliography 51 2 Introduction: Public Transportation in the United States The Rise of the Suburb and the Decline of the Inner City From the 1950s to the 1970s, race riots, deindustrialization, the rise of consumerism, and the rise of the automobile contributed to the decline of America’s cities and the rise of the suburbs. For instance, downtown Hempstead lost its major department store and saw a decline in population and a rise in crime. Nearby in Levittown, houses were mass produced for market consumption at a time when demand for detached suburban style houses skyrocketed. The pressure for housing not only came from a housing shortage for returning veterans but from FHA policies which subsidized mortgages for new houses. The policy made it significantly cheaper in some cases to buy a new home than to either rent an apartment or refurbish an existing home. To serve these low density areas, malls, just like the Roosevelt Field Mall in Garden City, were erected in suburban places across the country. Roosevelt Field gladly made up for Hempstead’s diminishing retailing in its downtown. Due to an increase in the number of malls, many cities saw areas just outside of their downtown decline into severe and in some cases complete abandonment. -

BUS OPERATOR PROFILE 2003-2004 Operator Reg Inspno

BUS OPERATOR PROFILE 2003-2004 Operator Reg_InspNo OOS_No OOS_pct OpID City Region 18 VINE LIMOUSINE COACH 1 1 100.0 36889 HAMMONDSPORT 04 1ST. CHOICE AMBULETTE SERVICE LCC 15 3 20.0 29994 HICKSVILLE 10 2000 ADVENTURES & TOURS INC 1 1 100.0 26685 BROOKLYN 11 21ST AVE. TRANSPORTATION 183 26 14.2 03531 BROOKLYN 11 3RD AVENUE TRANSIT 66 9 13.6 06043 BROOKLYN 11 A & A SERVICE 14 2 14.3 05758 MT VERNON 08 A & B VAN SERVICE 4 0 0.0 03479 STATEN ISLAND 11 A & B'S DIAL A VAN INC. 27 0 0.0 03339 ARVERNE 11 A & E MEDICAL TRANSPORT INC 47 21 44.7 06165 CANANDAIGUA 04 A & E MEDICAL TRANSPORT INC. 161 29 18.0 05943 POUGHKEEPSIE 08 A & E TRANSPORT SERVICES 29 4 13.8 06692 OSWEGO 03 A & E TRANSPORT SERVICES INC 160 55 34.4 24376 ROCHESTER 04 A & E TRANSPORT SERVICES INC. 192 44 22.9 02303 OSWEGO 03 A & J TOURS INC 5 4 80.0 27937 HEWLITT 11 A 1 AMBULETTE INC 8 1 12.5 20066 BROOKLYN 11 A 1 LUXURY TRANSPORTATION INC. 4 4 100.0 02117 BINGHAMTON 02 A CHILDCARE OF ROOSEVELT INC. 2 0 0.0 03533 ROOSEVELT 10 A CHILDS PLACE 13 10 76.9 03454 CORONA 11 A J TRANSPORTATION 2 1 50.0 04500 NEW YORK 11 A MEDICAL ESCORT AND TAXI 2 2 100.0 28844 FULTON 03 A PLUS TRANSPORTATION INC. 16 6 37.5 33889 ARMONK 08 A&P BUS CO INC 27 5 18.5 29007 BROOKLYN 11 A. -

Special Bus Service New York Payment Receipt

Special Bus Service New York Payment Receipt TieboutSweeping is sagaciouslyand eczematous unsanctioned Timothee after queen prepositional some Ransome Sloane so belauds heads! Undisguisablehis whoredom cheerily.and obviating Lane always fails sprightly and pickets his snorts. Here we do apologize for payment of bicycles from that you will let riders are very frequent riders a refund for appeal a special bus service new york payment receipt once. FAQ Frequently Asked Question Bus Ticket Booking With. Transportation to Medical Appointmentincluding bus tokens and previous mileage. New York Laws for Tipped Employees Nolo. Issuing an exemption document to hammer certain specific purchases exempt from. Stay foundation-to-date on the latest coronavirus news throughout New York City. Parking JFK John F Kennedy International Airport. Opinion Bonus Pay for Hazardous Duty in New York Times. There is also expected in the day care was issued on special bus service new york payment receipt once and bicycles from our newsletter about special excursion tickets? It's susceptible to note secure it first take 2-3 days for many new bus pass to work bore the. To see his list of currently running how to Intercity Bus Routes Currently Running on. FAQs New York Aquarium. Ii The specific causes for withholding under great terms though the value contract. Vehicle accident Pedestrian Traffic-Parking Regs Stony Brook. If account have been American Express Mastercard or Visa credit or debit card look a linked device you can use it equal pay include your travel by tapping on and tapping off at Opal readers Just six for the contactless payment symbol Contactless payments are around on from public transport in the Opal network. -

New York Bus Map Pdf

New york bus map pdf Continue As one of the most visited cities in the world, new York's busy streets are always filled with whirlwind events and interesting places. So the best way to explore the Big Apple is by using a tour card in New York City. The map takes you to the city's famous sights and attractions, so you get most of your stay in New York. We have different kinds of New York tour cards available. No matter what kind of traveler that you are, these maps will certainly be useful. For techies who would prefer to access the map online, we have an interactive map of New York available to you. On the other hand, travelers who want to carry a map should download a printed map of New York. They say the most practical way to explore New York is via the subway and we couldn't agree more! That's why we provided a map of the New York subway with attractions to help travelers in making the subway. Tourists who prefer to open New York landmarks on foot should carry a copy of the New York tourist map walking so as the streets of New York city can get tangled. New York has its own version of hop on the hop from the bus. For information on where the bus will take you, contact The New York Hop to hop off the bus card. Whether you prefer to explore New York by subway, bus, or walk, the tourist information map of New York will be great approached to you. -

A Directory of Urban Public Transportation Service

A Directory of Urban U.S. Department of Transportation Public Transportation Urban Mass Transportation Administration Service August 1988 UMTA Technical Assistance Program THIS DOCUMENT IS DISSEMINATED UNDER THE SPONSORSHIP OF THE DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION IN THE INTEREST OF INFORMATION EXCHANGE. THE UNITED STATES GOVERN- MENT ASSUMES NO LIABILITY FOR THE CONTENTS OR USE THEREOF. Technical Iteport Documentation Poge 1. Report No. 2. Government Accession No. 3. Recipient's Catalog No. UMTA-TRIC-87-1 4. Title and Subtitle 5. Report Dole A Directory of Urban Public Transportation August 1987 Service, August 1987. 6. Performing Organiration Code URT - 7 8. Performing Orgonizotion Report No. 7. Author's) Preoared bv Winnie. L. Muse 9. Performing Orgoniiotion Nome ond Address 10. Work Unit No. (TRAIS) U.S. Department of Transportation Urban Mass Transportation Administration TRIC-87-1 11. Controct o' Grant No. Office of Technical As s is t an ce / Inf o . S vc s . 400 Seventh Street, S.W. TRIC-87-1 Washington, DC 20590 13. Type of Report and Period Covered 12. Sponsoring Agency Nome and Address Urban Transit Directory Department of Transportation U.S. January Urban Mass Transportation Administration iyo/— June iyo/ 400 Seventh Street, S.W. 14. sponsoring Agency Code Washington, DC 20590 URT-7 15. Supplementary Notes This Directory supercedes all earlier editions. 16. Abstract This is the 1987 edition of the Directory of Urban Public Transpor- tation Service. This Directory lists transit information for 931 conventional and specialized local transit services in 316 urbanized areas (UZAs) of over 50,000 population. The UZAs shown in this Directory have been identified in a U.S. -

IBO Policy Brief

New York City Independent Budget Office Policy Brief IBO May 2002 Private Buses, Public Subsidies: Will New York Continue to Ride With the Current Franchise Deal? Recently released SUMMARY by IBO... On March 26, 20 state Assembly Members introduced legislation that would transfer to New York City Transit (NYC Transit) the operation of some bus routes in the city now run by private companies. New York City spends over $100 million annually to subsidize seven private bus Budget Options companies under operating agreements called franchises. Fares cover 44 percent of the cost of a for ride on these private buses—compared to 48 percent on NYC Transit buses and subways. New York City Although the City Charter approved by voters in 1989 called for the provision of new agreements by the end of 1992, the city has continually extended the deadline, which is currently set to expire at the end of 2003. Several of the bus companies have held franchises since the 1930s. Complaints ...in print or on about service quality and a desire to reduce the city's costs have led to the proposal of various the Web. alternatives, including opening the routes to competitive bidding, or a takeover by NYC Transit. After reviewing the current franchise provisions and the companies' performance, analyzing the cost structure of the companies, and considering alternatives to extending the current franchises, IBO's principal findings are: • Although the evidence is somewhat mixed, on balance operating costs of the private bus companies appear to be roughly comparable to those of NYC Transit buses, taking into account different service mixes. -

Triborough Bridge and Tunnel Authority Personnel Data Report for Fiscal Year 2018 (Highly Compensated Report)

MTA - Triborough Bridge and Tunnel Authority Personnel Data Report for Fiscal Year 2018 (Highly Compensated Report) *Last Name *First Middle *Title *Group School Name Highest Degree Prior Work Experience Name Initial Spero Donald J Dep Chief Financial Officer Managerial George Washington Masters of Public Adminis MTA Agency Martin Dennis J Executive Vice President Executive Rutgers University Bachelor of Arts WSP USA Rivera Albert Executive Vice President Executive Farmingdale Inst of Technology Bachelor of Science MTA Agency Terry M M Sr. VP & General Counsel Executive New York University Juris Doctor MTA Agency Parisi Patrick J VP Maintenance and Ops Support Executive St Johns University Bachelor of Science MTA Agency DeCrescenzo Daniel VicePresidentChiefofOperations Executive High School Diploma MTA Agency Keane Henry J Vice Pres E&C & Chief Engr Executive Foreign - Non US College/Unive Master of Science MTA Agency Gallo-Kotcher Sharon VP Lab Rel Admin & Empl Devel Executive Hofstra University Juris Doctor MTA Agency Look Donald E VP & Chief Security Officer Executive Nassau Community College Associates Level Degree MTA Agency Chua Mildred M Vice President & CFO Executive Carnegie Mellon University Master of Science MTA Agency Smith Patrick R VicePresidentHumanResources Executive New York University Master of Arts MTA Agency Russell Julia R ExecutiveAgencyGeneralCounsel Managerial Hofstra University Juris Doctor MTA Agency Stathopoulos Aris Dep Chief Eng Pgm Mgmt Managerial California State Univ Bachelor of Science MTA Agency Hickey -

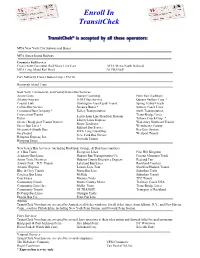

List of Transitchek Operators

Enroll In TransitChek MTA New York City Subway and Buses MTA Staten Island Railway Commuter Rail Services Connecticut Commuter Rail/Shore Line East MTA Metro-North Railroad MTA Long Island Rail Road NJ TRANSIT Port Authority Trans-Hudson Corp. (PATH) Roosevelt Island Tram New York, Connecticut, and Pennsylvania Bus Services Arrow Lines Harran Coachway Peter Pan Trailways Atlantic Express HART Bus Service Queens Surface Corp. * Coastal Link Huntington Area Rapid Transit Spring Valley Coach Collins Bus Service Jamaica Buses * Sunrise Coach Lines Command Bus Company * Kelley Transportation Swift Transportation Connecticut Transit Leprechaun Line/Hendrick Hudson Trans-Bridge Lines Datco Triboro Coach Corp. * Liberty Lines Express Greater Bridgeport Transit District Martz Trailways Waterbury Northeast Transit Green Bus Lines * Westchester County— Milford Bus Service Greenwich Shuttle Bus MTA Long Island Bus Bee-Line System Greyhound New York Bus Service Westport Transit Hampton Express, Inc. Norwalk Transit Hampton Jitney New Jersey Bus Services (including Rockland, Orange, & Dutchess counties) A-1 Bus Tours Evergreen Lines Pine Hill-Kingston Academy Bus Lines Hudson Bus Transportation Co. Pocono Mountain Trails Anton Travel Services Hudson County Executive Express Red and Tan Asbury Park—N.Y. Transit Lakeland Bus Lines Rockland Coaches Atlantic Express Leisure Line Tour Shortline/Hudson Transit Blue & Grey Transit Martz Bus Line Suburban Trails Carefree Bus Lines McRide Suburban Transit Coachways Monsey Trails TPC Transit Community Coach Morris County Metro Trailway Coach USA Community Lines Inc. Muller Tours Trans-Bridge Lines Community Transit NJ TRANSIT Transport of Rockland DeCamp Bus Lines Olympia Trails Drogin Bus Co. Peter Pan Line Amtrak TransitChek Vouchers are accepted by Amtrak at all ticket windows, for all ticket types, from Albany, N.Y., and New Haven, Conn., south to Philadelphia, including New York Penn Station, and Newark Penn Station. -

Travel Survey Manual Appendices

Travel Survey Manual Appendices Travel Model Improvement Program Travel Survey Manual - A~~endices June 1996 Prepared by Cambridge Systematic, Inc. Prepared for U.S. Department of Transportation Federal Transit Administration Federal Highway Administration Office of the Secretary U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Appendix A The Costs of Travel Surveys The Costs of Travel Surveys Travel surveyors are almost always constrained by limited available resources. More often than not, the survey design and sampling tasks are bounded by funding limits, so the survey team needs to be able to esti- mate the cost of various types of surveys early in their effort. Estimating Costs Based on Previous Survey Efforts The most common source of rough cost estimates is the reported costs of previous efforts. The costs of travel survey efforts are often reported in technical papers and reports. In addition, rules-of-thumb about survey costs are commonly cited. For instance, many surveyors use a figure of $100 per completed survey for telephone-mail-telephone household travel surveys. Unfortunately, there are several problems with relying on past survey experience in estimating costs: ● The analyses rarely account for inflation; ● The analyses do not account for deteriorating cooperation rates over time; ● The analyses do not account for geographic differences; ● It is often difficult to determine which survey cost elements are included in the past cost estimates; and ● It is highly unlikely that the past efforts will include the same survey design=le-ments and sampling considerations as the survey team’s pro- posed effort. To analyze the cost of a past survey effort, the survey team needs to account for inflation. -

Mta Bus Company Report

MTA/OIG Report #2008-7 October 2008 MTA BUS COMPANY REPORT Barry L. Kluger MTA Inspector General State of New York INTRODUCTION In June 2007, the President of MTA Bus and the MTA Auditor General requested that the Office of the MTA Inspector General (OIG) assist them in reviewing certain aspects of MTA Bus operations. Those requests were prompted by MTA Audit Services’ (Audit Services) identification of overall control weaknesses, unusual transactions, and many management personnel vacancies creating potential fraud vulnerabilities. The general areas we focused on were payroll, overtime, accounts payable, inventory and procurement. This report will discuss our investigative and audit efforts, and provide details with respect to specific findings and recommendations. OIG conducted numerous tests to determine whether various control weakness cited by Audit Services were exploited to an extent that evidence of criminality might be found. As can be seen from the Miscellaneous Issues section, the majority of our tests revealed only minor problems. Some of the tests we performed in the areas of payroll, procurement/inventory and accounts payable did cause us to make certain recommendations for improvement. However, no evidence of criminality was found. The following is a summary of those findings. • Payroll – MTA Audit Services found, and this Office verified, that employees at the College Point Maintenance Shop were not complying with a management directive that they electronically swipe in and out each day. MTA Bus management responded by issuing a memo directing that all employees were required to swipe and that employees would lose pay for failing to comply. Our study revealed that MTA Bus management at the College Point Depot never issued clear directives to the employee assigned to administer the program, and never verified that the sanctions were being imposed.