Uva-DARE (Digital Academic Repository)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

How Did America Inspire Indonesian Revolution?

How Did America Inspire Indonesian Revolution? I Basis Susilo & Annisa Pratamasari Universitas Airlangga ABSTRACT This paper examines the American Revolution as an inspiration for Indonesia’s founding fathers to fight for their nation’s independence in 1945. This paper was sparked by the existence of the pamphlet ‘It’s 1776 in Indonesia’ published in 1948 in the United States which presupposes the link between Indonesian Revolution and the American Revolution. The basic assumption of this paper is that Indonesian founding fathers were inspired by the experiences of other nations, including the Americans who abolished the British colonization of 13 colonies in North American continent in the eigthenth century. American inspiration on the struggle for Indonesian independence was examined from the spoken dan written words of three Indonesian founding fathers: Achmad Soekarno, Mohamad Hatta, and Soetan Sjahrir. This examination produced two findings. First, the two Indonesian founding fathers were inspired by the United States in different capacities. Compared to Hatta and Sjahrir, Soekarno referred and mentioned the United States more frequent. Second, compared to the inspirations from other nations, American inspiration for the three figures was not so strong. This was because the liberal democratic system and the American-chosen capitalist system were not the best alternative for Soekarno, Hatta, and Sjahrir. Therefore, the massive exposition of the 1776 Revolution in 1948 was more of a tactic on the Indonesian struggle to achieve its national objectives at that time, as it considered the United States as the most decisive international post-World War II political arena. Keywords: United States, Indonesia, Revolution, Inspiration, Soekarno, Hatta, Sjahrir. -

Review the Mind of Mohammad Hatta for the Contemporary of Indonesian Democracy

Review the Mind of Mohammad Hatta for the Contemporary of Indonesian Democracy Farid Luthfi Assidiqi 1 {[email protected]} 1 Universitas Diponegoro, Indonesia 1 Abstract. Mohammad Hatta is one of the founders of the nation, as well as a thinker who controls various Western disciplines, but still adheres to Indonesian values. His thoughts on democracy include popular democracy and economic democracy with the principle of popular sovereignty. The results of this study are that all elements of the nation need to actualize the thinking of Mohammad Hatta trying to apply the concept of Democratic Democracy and Economic Democracy by re-learning his concept of thought and making policies that enable Mohammad Hatta's democratic concept to be implemented. Keywords: People's Sovereignty, Popular Democracy, Economic Democracy. 1 Introduction Mohammad Hatta or familiarly called Bung Hatta was one of the thinkers who became the founding father of the Indonesian nation. Bung Hatta, the first hero of the Indonesian Proclamator and Deputy President, has laid the foundations of nation and state through struggle and thought enshrined in the form of written works. Bung Hatta had been educated in the Netherlands but because Nationalism and his understanding of Indonesia made his work very feasible to study theoretically. Bung Hatta devoted his thoughts by writing various books and writing columns in various newspapers both at home and abroad. It has been known together that Bung Hatta's work was so diverse, his thinking about nationalism, Hatta implemented the idea of nationalism that had arisen since school through his politics of movement and leadership in the movement organization at the Indonesian Association and Indonesian National Education. -

A Note on the Sources for the 1945 Constitutional Debates in Indonesia

Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde Vol. 167, no. 2-3 (2011), pp. 196-209 URL: http://www.kitlv-journals.nl/index.php/btlv URN:NBN:NL:UI:10-1-101387 Copyright: content is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License ISSN: 0006-2294 A.B. KUSUMA AND R.E. ELSON A note on the sources for the 1945 constitutional debates in Indonesia In 1962 J.H.A. Logemann published an article entitled ‘Nieuwe gegevens over het ontstaan van de Indonesische grondwet van 1945’ (New data on the creation of the Indonesian Constitution of 1945).1 Logemann’s analysis, presented 48 years ago, needs revisiting since it was based upon a single work compiled by Muhammad Yamin (1903-1962), Naskah persiapan Undang-undang Dasar 1945 (Documents for the preparation of the 1945 Constitution).2 Yamin’s work was purportedly an edition of the debates conducted by the Badan Penyelidik Usaha Persiapan Kemerdekaan (BPUPK, Committee to Investigate Preparations for Independence)3 between 29 May and 17 July 1945, and by the 1 Research for this article was assisted by funding from the Australian Research Council’s Dis- covery Grant Program. The writers wish to thank K.J.P.F.M. Jeurgens for his generous assistance in researching this article. 2 Yamin 1959-60. Logemann (1962:691) thought that the book comprised just two volumes, as Yamin himself had suggested in the preface to his first volume (Yamin 1959-60, I:9-10). Volumes 2 and 3 were published in 1960. 3 The official (Indonesian) name of this body was Badan oentoek Menjelidiki Oesaha-oesaha Persiapan Kemerdekaan (Committee to Investigate Preparations for Independence) (see Soeara Asia, 1-3-1945; Pandji Poestaka, 15-3-1945; Asia Raya, 28-5-1945), but it was often called the Badan Penjelidik Oesaha(-oesaha) Persiapan Kemerdekaan (see Asia Raya, 28-5-1945 and 30-5-1945; Sinar Baroe, 28-5-1945). -

Another Look at the Jakarta Charter Controversy of 1945

Another Look at the Jakarta Charter Controversy of 1945 R. E. Elson* On the morning of August 18, 1945, three days after the Japanese surrender and just a day after Indonesia's proclamation of independence, Mohammad Hatta, soon to be elected as vice-president of the infant republic, prevailed upon delegates at the first meeting of the Panitia Persiapan Kemerdekaan Indonesia (PPKI, Committee for the Preparation of Indonesian Independence) to adjust key aspects of the republic's draft constitution, notably its preamble. The changes enjoined by Hatta on members of the Preparation Committee, charged with finalizing and promulgating the constitution, were made quickly and with little dispute. Their effect, however, particularly the removal of seven words stipulating that all Muslims should observe Islamic law, was significantly to reduce the proposed formal role of Islam in Indonesian political and social life. Episodically thereafter, the actions of the PPKI that day came to be castigated by some Muslims as catastrophic for Islam in Indonesia—indeed, as an act of treason* 1—and efforts were put in train to restore the seven words to the constitution.2 In retracing the history of the drafting of the Jakarta Charter in June 1945, * This research was supported under the Australian Research Council's Discovery Projects funding scheme. I am grateful for the helpful comments on and assistance with an earlier draft of this article that I received from John Butcher, Ananda B. Kusuma, Gerry van Klinken, Tomoko Aoyama, Akh Muzakki, and especially an anonymous reviewer. 1 Anonymous, "Naskah Proklamasi 17 Agustus 1945: Pengkhianatan Pertama terhadap Piagam Jakarta?," Suara Hidayatullah 13,5 (2000): 13-14. -

Danilyn Rutherford

U n p a c k in g a N a t io n a l H e r o in e : T w o K a r t in is a n d T h e ir P e o p l e Danilyn Rutherford As Head of the Country, I deeply regret that among the people there are still those who doubt the heroism of Kartini___Haven't we already unanimously decided that Kartini is a National Heroine?1 On August 11,1986, as Dr. Frederick George Peter Jaquet cycled from Den Haag to his office in Leiden, no one would have guessed that he was transporting an Indonesian nation al treasure. The wooden box strapped to his bicycle looked perfectly ordinary. When he arrived at the Koninklijk Instituut voor Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde, the scholar opened the box to view the Institute's long-awaited prize: a cache of postcards, photographs, and scraps of letters sent by Raden Adjeng Kartini and her sisters to the family of Mr. J. H. Abendanon, the colonial official who was both her patron and publisher. From this box so grudgingly surrendered by Abendanon's family spilled new light on the life of this Javanese nobleman's daughter, new clues to the mystery of her struggle. Dr. Jaquet's discovery, glowingly reported in the Indonesian press, was but the latest episode in a long series of attempts to liberate Kartini from the boxes which have contained her. For decades, Indonesian and foreign scholars alike have sought to penetrate the veils obscuring the real Kartini in order to reach the core of a personality repressed by colonial officials, Dutch artists and intellectuals, the strictures of tradition, and the tragedy of her untimely death. -

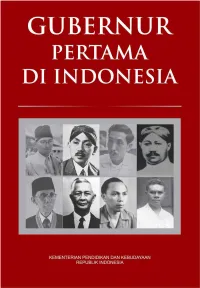

Teuku Mohammad Hasan (Sumatra), Soetardjo Kartohadikoesoemo (Jawa Barat), R

GUBERNUR PERTAMA DI INDONESIA GUBERNUR PERTAMA DI INDONESIA KEMENTERIAN PENDIDIKAN DAN KEBUDAYAAN REPUBLIK INDONESIA GUBERNUR PERTAMA DI INDONESIA PENGARAH Hilmar Farid (Direktur Jenderal Kebudayaan) Triana Wulandari (Direktur Sejarah) NARASUMBER Suharja, Mohammad Iskandar, Mirwan Andan EDITOR Mukhlis PaEni, Kasijanto Sastrodinomo PEMBACA UTAMA Anhar Gonggong, Susanto Zuhdi, Triana Wulandari PENULIS Andi Lili Evita, Helen, Hendi Johari, I Gusti Agung Ayu Ratih Linda Sunarti, Martin Sitompul, Raisa Kamila, Taufik Ahmad SEKRETARIAT DAN PRODUKSI Tirmizi, Isak Purba, Bariyo, Haryanto Maemunah, Dwi Artiningsih Budi Harjo Sayoga, Esti Warastika, Martina Safitry, Dirga Fawakih TATA LETAK DAN GRAFIS Rawan Kurniawan, M Abduh Husain PENERBIT: Direktorat Sejarah Direktorat Jenderal Kebudayaan Kementerian Pendidikan dan Kebudayaan Jalan Jenderal Sudirman, Senayan Jakarta 10270 Tlp/Fax: 021-572504 2017 ISBN: 978-602-1289-72-3 SAMBUTAN Direktur Sejarah Dalam sejarah perjalanan bangsa, Indonesia telah melahirkan banyak tokoh yang kiprah dan pemikirannya tetap hidup, menginspirasi dan relevan hingga kini. Mereka adalah para tokoh yang dengan gigih berjuang menegakkan kedaulatan bangsa. Kisah perjuangan mereka penting untuk dicatat dan diabadikan sebagai bahan inspirasi generasi bangsa kini, dan akan datang, agar generasi bangsa yang tumbuh kelak tidak hanya cerdas, tetapi juga berkarakter. Oleh karena itu, dalam upaya mengabadikan nilai-nilai inspiratif para tokoh pahlawan tersebut Direktorat Sejarah, Direktorat Jenderal Kebudayaan, Kementerian Pendidikan dan Kebudayaan menyelenggarakan kegiatan penulisan sejarah pahlawan nasional. Kisah pahlawan nasional secara umum telah banyak ditulis. Namun penulisan kisah pahlawan nasional kali ini akan menekankan peranan tokoh gubernur pertama Republik Indonesia yang menjabat pasca proklamasi kemerdekaan Indonesia. Para tokoh tersebut adalah Teuku Mohammad Hasan (Sumatra), Soetardjo Kartohadikoesoemo (Jawa Barat), R. Pandji Soeroso (Jawa Tengah), R. -

Exploring the History of Indonesian Nationalism

University of Vermont ScholarWorks @ UVM Graduate College Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses 2021 Developing Identity: Exploring The History Of Indonesian Nationalism Thomas Joseph Butcher University of Vermont Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uvm.edu/graddis Part of the Asian History Commons, and the South and Southeast Asian Languages and Societies Commons Recommended Citation Butcher, Thomas Joseph, "Developing Identity: Exploring The History Of Indonesian Nationalism" (2021). Graduate College Dissertations and Theses. 1393. https://scholarworks.uvm.edu/graddis/1393 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Dissertations and Theses at ScholarWorks @ UVM. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate College Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ UVM. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DEVELOPING IDENTITY: EXPLORING THE HISTORY OF INDONESIAN NATIONALISM A Thesis Presented by Thomas Joseph Butcher to The Faculty of the Graduate College of The University of Vermont In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Specializing in History May, 2021 Defense Date: March 26, 2021 Thesis Examination Committee: Erik Esselstrom, Ph.D., Advisor Thomas Borchert, Ph.D., Chairperson Dona Brown, Ph.D. Cynthia J. Forehand, Ph.D., Dean of the Graduate College Abstract This thesis examines the history of Indonesian nationalism over the course of the twentieth century. In this thesis, I argue that the country’s two main political leaders of the twentieth century, Presidents Sukarno (1945-1967) and Suharto (1967-1998) manipulated nationalist ideology to enhance and extend their executive powers. The thesis begins by looking at the ways that the nationalist movement originated during the final years of the Dutch East Indies colonial period. -

BAB I PENDAHULUAN 1.1 Latar Belakang Konsepan Awal Piagam

BAB I PENDAHULUAN 1.1 Latar Belakang Konsepan awal Piagam Madinah adalah kesepakatan (jalan tengah) untuk menghindari konflik dan juga tidak memihak pihak tertentu di Madinah pada abad ke-7 Masehi, karena Madinah terkenal dengan masyarakat yang Multikulturalnya dan Multi-religi. Piagam Madinah juga disebut sebagai konstitusi negara pada saat itu karena dibuat untuk mempersatukan golongan Yahudi dan Bani Qoinuqo, Bani Nadhir dan juga Bani Quraidlah, yaitu masyarakat yang ada di Madinah pada masa itu yang langsung di bentuk oleh Nabi Muhammad saw, untuk membentuk suatu perjanjian yang isinya melindungi hak-hak azasi manusia dan hidup rukun berdampingan antar umat Beragama ada pula makud dan tujuan dari dibentuknya piagam madinah ini misalkan komunitas muslim diserang oleh komunistas lain dari luar maka komunitas yahudi harus membantu dan begitupun sebaliknya. Pluralitas masyarakat Madinah tersebut tidak luput dari pengamatan Nabi. Beliau menyadari, tanpa adanya acuan bersama yang mengatur pola hidup masyarakat yang majemuk itu, konflik-konflik diantara berbagai golongan itu akan menjadi konflik terbuka dan pada suatu saat akan mengancam persatuan dan kesatuan kota Madinah.Piagam Madinah yang dibuat Rasulullah mengikat seluruh penduduk yang terdiri dari berbagai kalibah (Kaum) yang menjadi penduduk Madinah. (Astuti, 2012: 24). 1 2 Sebelum di nabi hijrah ke madinah terjadi konflik di Yathrib maka dimintalah nabi hajrah untuk mendamaikan koflik tersebut dan membuat konstitusi Madinah atau Piagam Madinah, konstitusi Madinah ialah sebuah dokum yang disusun oleh Nabi Muhammad SAW, yang merupakan perjanjian formal semua masyarakat di Yathrib (Kemudian bernama Madinah). Dokumen tersebut disusun sejelas-jelasnya dengan tujuan untuk menghentikan pertentangan sengit antara Bani `Aus dan Bani Khazraj di Madinah. -

H. Bachtiar Bureaucracy and Nation Formation in Indonesia In

H. Bachtiar Bureaucracy and nation formation in Indonesia In: Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde 128 (1972), no: 4, Leiden, 430-446 This PDF-file was downloaded from http://www.kitlv-journals.nl Downloaded from Brill.com09/26/2021 09:13:37AM via free access BUREAUCRACY AND NATION FORMATION IN INDONESIA* ^^^tudents of society engaged in the study of the 'new states' in V J Asia and Africa have often observed, not infrequently with a note of dismay, tihe seeming omnipresence of the government bureau- cracy in these newly independent states. In Indonesia, for example, the range of activities of government functionaries, the pegawai negeri in local parlance, seems to be un- limited. There are, first of all and certainly most obvious, the large number of people occupying official positions in the various ministries located in the captital city of Djakarta, ranging in each ministry from the authoritative Secretary General to the nearly powerless floor sweepers. There are the territorial administrative authorities, all under the Minister of Interna! Affairs, from provincial Governors down to the village chiefs who are electecl by their fellow villagers but who after their election receive their official appointments from the Govern- ment through their superiors in the administrative hierarchy. These territorial administrative authorities constitute the civil service who are frequently idenitified as memibers of the government bureaucracy par excellence. There are, furthermore, as in many another country, the members of the judiciary, personnel of the medical service, diplomats and consular officials of the foreign service, taxation officials, technicians engaged in the construction and maintenance of public works, employees of state enterprises, research •scientists, and a great number of instruc- tors, ranging from teachers of Kindergarten schools to university professors at the innumerable institutions of education operated by the Government in the service of the youthful sectors of the population. -

Can Religion Prevents Corruption? the Indonesian Experience

Al WASATH Jurnal Ilmu Hukum Volume 1 No. 1 April 2020: 13-24 CAN RELIGION PREVENTS CORRUPTION? THE INDONESIAN EXPERIENCE Kartini Laras Makmur Mohammad Hatta Center E-mail: [email protected] ABSTRAK Sejumlah penelitian anti-korupsi telah menyatakan bahwa politik, ekonomi, dan kebudayaan berpengaruh terhadap praktik korupsi. Lantas bagaimana dengan pengaruh agama terhadap korupsi? Belakangan, hubungan antara agama terhadap korupsi memunculkan pertanyaan: dapatkah agama mencegah korupsi? Tulisan ini membahas dampak religiusitas dalam korupsi birokrasi di Indonesia. Pada bagian hasil, menunjukkan bahwa praktik korupsi secara negatif diasosiasikan dengan ajaran agama, menunjukkan agama memiliki peran positif dalam pencegahan korupsi berkenaan dengan ajaran normatif anti-korupsi dalam agama itu sendiri. Tulisan ini juga menyatakan hubungan negatif antara agama dan korupsi adalah lebih lemah pada kelompok yang memiliki pengalaman dimintakan pemberian sejumlah “uang pelicin” oleh petugas. Temuan tersebut mengidentifikasikan substisusi antara etika agama dan penegakan hukum dalam pemberantasan korupsi. Dengan terbatasnya studi dan data pada bidang penelitian yang sama, tulisan ini semata adalah studi tentatif untuk berkontribusi pada topik antara hubungan agama dan perilaku korupsi. Kata kunci: Agama dan korupsi, pencegahan korupsi, praktik korupsi. ABSTRACT Researches on Anti-Corruption have found that politics, economics, and culture have a relation to corrupt practices. However, what about the influence of religion on corruption? Recently, there is an increasing interest in understanding the relationship between religion and corruption; could religion prevent corruption? This paper discusses the effect of religiosity on bureaucratic corruption in Indonesia. The results show that corrupt practices are negatively associated with religious heritage, signifying that religious culture takes a positive role in delimiting corrupt practices of government officials since religion has an influence on the normative anti-corruption paradigm. -

Keberhasilan Hukum Islam Menerjang Belenggu Kolonial Dan Menjaga Keutuhan Nasional

Keberhasilan Hukum Islam Menerjang Belenggu Kolonial dan...; Faiq Tobroni Keberhasilan Hukum Islam Menerjang Belenggu Kolonial dan Menjaga Keutuhan Nasional Faiq Tobroni E-mail : [email protected] The receptie exit theory of Hazairin has freed Islamic Law from legal colonization as a result of the receptie theory. Since the independence day, the receptie theory has not been effective any longer, because since then Pancasila has been the main source of laws, including Islamic Law, without any subordination. However, the inclusion of the word “Is- lam” in the previous Pancasila, known as Piagam jakarta, had been controversial. Never- theless, Hatta had been successful to cope with the problem by substituting the contro- versial word in the first principle to the symbolic word of “Oneness” which remains to contain Islamic spirit. This choice has succeeded to defend Indonesian state integrity. Keywords: receptie exit, receptie, colonization, state integrity. Pendahuluan bahwa teori ini hanyalah mainan Belanda untuk menjaga kekuasaannya aman di In- ebelum memasuki pintu kemerdekaan, donesia. Teori dari Hazairin ini adalah teori hukum Islam mengalami perlakuan S receptie exit. Teori ini merupakan instrumen marginalisasi oleh pemerintah kolonial. untuk mengembalikan kedudukan hukum Hukum Islam telah dirugikan teori receptie Islam sebagai mitra hukum adat. Sebe- yang disponsori oleh Cornelis van Vollen- lumnya, menurut teori receptie, hukum Is- hoven (1874-1993) dan kemudian diteruskan lam berada di bawah hukum adat. Di bawah Cristian Snouck Hurgronje (1857-1936). teori receptie ini, hukum Islam mendapat Melalui teori ini, seolah-olah hukum Islam segudang stigma negatif termasuk penyu- terletak inferior di bawah hukum adat. dutan kedudukan Islam sebagai pemecah Penulis Barat/Belanda menggambarkan belah keutuhan nasional. -

Traces of the Socialist in Exile: Mohammad Hatta and Sutan Sjahrir

The Journal of Society and Media, April 2020, Vol. 4(1) 133-155 https://journal.unesa.ac.id/index.php/jsm/index E-ISSN 2580-1341 and P-ISSN 2721-0383 Accredited No.36/E/KPT/2019 DOI: 10.26740/jsm.v4n1.p133-155 Traces of The Socialist in Exile: Mohammad Hatta and Sutan Sjahrir Muhammad Farid1* 1Lecture of Social Science, STKIP Hatta-Sjahrir, Banda Naira, Maluku Tengah, Indonesia Nusantara, Banda, Kabupaten Maluku Tengah, Maluku, Indonesia Email: [email protected] Abstract This paper aims to reveal the traces of the two national figures, Mohammad Hatta and Sutan Sjahrir during exile in Banda Naira. Both are warrior figures that are difficult to forget in the history of the nation. But their popularity was barely revealed during their exile in Banda Naira. In fact, the legacy of their thoughts and role models is needed to respond to the crisis of leaders who have morality and integrity for Indonesia, and at the same time respond to the challenges of the global era. This paper based on the results of qualitative-historical research, using a phenomenological perspective, especially on the narratives of everyday life of Hatta and Sjahrir in exile Banda. The results of this study indicate that Hatta and Sjahrir were both patriots and educators even they were far away in exile. They built an "Kelas Sore" for Banda children, teaching the values of everyday life, including; religious-ethics, self-integrity, and nationalism. These values are become valuable exemplary for todays young generation, and especially for the people of Banda Naira.