Number 14 •PROCEEDINGS of 1982/1983 September, 1983 MAPUTO

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Humanitarian Service Medal - Approved Operations Current As Of: 16 July 2021

Humanitarian Service Medal - Approved Operations Current as of: 16 July 2021 Operation Start Date End Date Geographic Area1 Honduras, guatamala, Belize, El Salvador, Costa Rica, Dominican Republic, Hurricanes Eta and Iota 5-Nov-20 5-Dec-20 Nicaragua, Panama, and Columbia, adjacent airspace and adjacent waters within 10 nautical miles Port of Beirut Explosion Relief 4-Aug-20 21-Aug-20 Beirut, Lebanon DoD Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) 31-Jan-20 TBD Global Operations / Activities Military personnel who were physically Australian Bushfires Contingency Operations 1-Sep-19 31-Mar-20 present in Australia, and provided and Operation BUSHFIRE ASSIST humanitarian assistance Cities of Maputo, Quelimane, Chimoio, Tropical Cyclone Idai 23-Mar-19 13-Apr-19 and Beira, Mozambique Guam and U.S. Commonwealth of Typhoon Mangkhut and Super Typhoon Yutu 11-Sep-18 2-Feb-19 Northern Mariana Islands Designated counties in North Carolina and Hurricane Florence 7-Sep-18 8-Oct-18 South Carolina California Wild Land Fires 10-Aug-18 6-Sep-18 California Operation WILD BOAR (Tham Luang Nang 26-Jun-18 14-Jul-18 Thailand, Chiang Rai Region Non Cave rescue operation) Tropical Cyclone Gita 11-Feb-18 2-May-18 American Samoa Florida; Caribbean, and adjacent waters, Hurricanes Irma and Maria 8-Sep-17 15-Nov-17 from Barbados northward to Anguilla, and then westward to the Florida Straits Hurricane Harvey TX counties: Aransas, Austin, Bastrop, Bee, Brazoria, Calhoun, Chambers, Colorado, DeWitt, Fayette, Fort Bend, Galveston, Goliad, Gonzales, Hardin, Harris, Jackson, Jasper, Jefferson, Karnes, Kleberg, Lavaca, Lee, Liberty, Matagorda, Montgomery, Newton, 23-Aug-17 31-Oct-17 Texas and Louisiana Nueces, Orange, Polk, Refugio, Sabine, San Jacinto, San Patricio, Tyler, Victoria, Waller, and Wharton. -

Mozambique Zambia South Africa Zimbabwe Tanzania

UNITED NATIONS MOZAMBIQUE Geospatial 30°E 35°E 40°E L a k UNITED REPUBLIC OF 10°S e 10°S Chinsali M a l a w TANZANIA Palma i Mocimboa da Praia R ovuma Mueda ^! Lua Mecula pu la ZAMBIA L a Quissanga k e NIASSA N Metangula y CABO DELGADO a Chiconono DEM. REP. OF s a Ancuabe Pemba THE CONGO Lichinga Montepuez Marrupa Chipata MALAWI Maúa Lilongwe Namuno Namapa a ^! gw n Mandimba Memba a io u Vila úr L L Mecubúri Nacala Kabwe Gamito Cuamba Vila Ribáué MecontaMonapo Mossuril Fingoè FurancungoCoutinho ^! Nampula 15°S Vila ^! 15°S Lago de NAMPULA TETE Junqueiro ^! Lusaka ZumboCahora Bassa Murrupula Mogincual K Nametil o afu ezi Namarrói Erego e b Mágoè Tete GiléL am i Z Moatize Milange g Angoche Lugela o Z n l a h m a bez e i ZAMBEZIA Vila n azoe Changara da Moma n M a Lake Chemba Morrumbala Maganja Bindura Guro h Kariba Pebane C Namacurra e Chinhoyi Harare Vila Quelimane u ^! Fontes iq Marondera Mopeia Marromeu b am Inhaminga Velha oz P M úngu Chinde Be ni n è SOFALA t of ManicaChimoio o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o gh ZIMBABWE o Bi Mutare Sussundenga Dondo Gweru Masvingo Beira I NDI A N Bulawayo Chibabava 20°S 20°S Espungabera Nova OCE A N Mambone Gwanda MANICA e Sav Inhassôro Vilanculos Chicualacuala Mabote Mapai INHAMBANE Lim Massinga p o p GAZA o Morrumbene Homoíne Massingir Panda ^! National capital SOUTH Inhambane Administrative capital Polokwane Guijá Inharrime Town, village o Chibuto Major airport Magude MaciaManjacazeQuissico International boundary AFRICA Administrative boundary MAPUTO Xai-Xai 25°S Nelspruit Main road 25°S Moamba Manhiça Railway Pretoria MatolaMaputo ^! ^! 0 100 200km Mbabane^!Namaacha Boane 0 50 100mi !\ Bela Johannesburg Lobamba Vista ESWATINI Map No. -

Delegated Management of Urban Water Supply Services in MOZAMBIQUE

DELEGATED MANAGEMENT OF URBAN WATER SUPPLY SERVICES IN MOZAMBIQUE SUMMARY OF THE CASE STUDY OF FIPAG & CRA Delegated management of urban water supply services in Mozambique encountered a string of difficulties soon after it was introduced in 1999, but in 2007 a case study revealed that most problems had been overcome and the foundations for sustainability had been established. The government’s strong commitment, the soundness of the institutional reform and the quality of sector leadership can be credited for these positive results. Donor support for investments and institutional development were also important. Results reported here are as of the end of 2007. hen the prolonged civil war in Mozambique ended in exacerbated by the floods of 2000 and delays in the 1992, water supply infrastructure had deteriorated. implementation of new investments – and in December 2001 WIn 1998, the Government adopted a comprehensive SAUR terminated its involvement. Subsequently FIPAG and AdeM’s institutional reform for the development, delivery and regulation remaining partners led by Águas de Portugal (AdeP) renegotiated of urban water supply services in large cities. The new framework, the contracts, introducing higher fees and improvements in the known as the Delegated Management Framework (DMF), was specification of service obligations and procedures. The Revised inaugurated with the creation of two autonomous public bodies: Lease Contract became effective in April 2004, and will terminate an asset management agency (FIPAG) and an independent on November 30, 2014, fifteen years after the starting date of regulator (CRA). the Original Lease Contract. A new Management Contract for the period April 2004 – March 2007 consolidated the four Lease and Management Contracts with Águas de Original Management Contracts. -

Maputo, Mozambique Casenote

Transforming Urban Transport – The Role of Political Leadership TUT-POL Sub-Saharan Africa Final Report October 2019 Case Note: Maputo, Mozambique Lead Author: Henna Mahmood Harvard University Graduate School of Design 1 Acknowledgments This research was conducted with the support of the Volvo Foundation for Research and Education. Principal Investigator: Diane Davis Senior Research Associate: Lily Song Research Coordinator: Devanne Brookins Research Assistants: Asad Jan, Stefano Trevisan, Henna Mahmood, Sarah Zou 2 MAPUTO, MOZAMBIQUE MOZAMBIQUE Population: 27,233,789 (as of July 2018) Population Growth Rate: 2.46% (2018) Median Age: 17.3 GDP: USD$37.09 billion (2017) GDP Per Capita: USD$1,300 (2017) City of Intervention: Maputo Urban Population: 36% of total population (2018) Urbanization Rate: 4.35% annual rate of change (2015-2020 est.) Land Area: 799,380 sq km Roadways: 31,083 km (2015) Paved Roadways: 7365 km (2015) Unpaved Roadways: 23,718 km (2015) Source: CIA Factbook I. POLITICS & GOVERNANCE A. Multi- Scalar Governance Sixteen years following Mozambique’s independence in 1975 and civil war (1975-1992), the government of Mozambique began to decentralize. The Minister of State Administration pushed for greater citizen involvement at local levels of government. Expanding citizen engagement led to the question of what role traditional leaders, or chiefs who wield strong community influence, would play in local governance.1 Last year, President Filipe Nyusi announced plans to change the constitution and to give political parties more power in the provinces. The Ministry of State Administration and Public Administration are also progressively implementing a decentralization process aimed at transferring the central government’s political and financial responsibilities to municipalities (Laws 2/97, 7-10/97, and 11/97).2 An elected Municipal Council (composed of a Mayor, a Municipal Councilor, and 12 Municipal Directorates) and Municipal Assembly are the main governing bodies of Maputo. -

Transition Towards Green Growth in Mozambique

GREEN GROWTH MOZAMBIQUE POLICY REVIEW AND RECOMMENDATIONS FOR ACTION Transition Towards Green Growth in Mozambique and 2015 - 2015 All rights reserved. Printed in Côte d’Ivoire, designed by MZ in Tunisia - 2015 This knowledge product is part of the work undertaken by the African Development Bank in the context of its new Strategy 2013-2022, whose twin objectives are “inclusive and increasingly green growth”. The Bank provides technical assistance to its regional member countries for embarking on a green growth pathway. Mozambique is one of these countries. The Bank team is grateful to the Government of Mozambique, national counterparts, World Wildlife Fund (WWF), United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) and United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) for participating in the preparation and review of this report. Without them, this work would not have been possible. We acknowledge the country’s collective efforts to mainstream green growth into the new National Development Strategy and to build a more sustainable development model that benefits all Mozambicans, while preserving the country’s natural capital. A team from the African Development Bank, co-led by Joao Duarte Cunha (ONEC) and Andre Almeida Santos (MZFO), prepared this report with the support of Eoin Sinnot, Prof. Almeida Sitoe and Ilmi Granoff as consultants. Key sector inputs were provided by a multi-sector team comprised of Yogesh Vyas (CCCC), Jean-Louis Kromer and Cesar Tique (OSAN), Cecile Ambert (OPSM), Aymen Ali (OITC) and Boniface Aleboua (OWAS). Additional review and comments were provided by Frank Sperling and Florence Richard (ONEC) of the Bank-wide Green Growth team, as well as Emilio Dava (MZFO) and Josef Loening (TZFO). -

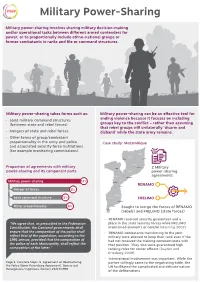

Military Power-Sharing

Military Power-Sharing Military power-sharing involves sharing military decision-making and/or operational tasks between dierent armed contenders for power; or to proportionally include ethno-national groups or former combatants in ranks and file or command structures. Military power-sharing takes forms such as: Military power-sharing can be an eective tool for • Joint military command structures ending violence because it focuses on including (between state and rebel forces) groups key to the conflict – rather than assuming that rebel groups will unilaterally ‘disarm and • Mergers of state and rebel forces disband’ while the state army remains. • Other forms of group/combatant proportionality in the army and police Case study: Mozambique and associated security force institutions (for example monitoring commissions). CABO DELGADO NIASSA LICHINGA PEMBA NAMPULA TETE NAMPULA Proportion of agreements with military TETE 2 Military power-sharing and its component parts ZAMBEZIA power-sharing MANICA agreements QUELIMANE SOFALA Military power-sharing 13% CHIMOIO BEIRA RENAMO Merger of forces 8% INHAMBANE Joint command structure 5% GAZA FRELIMO INHAMBANE Other proportionality 6% XAI-XAI Sought to merge the forces of RENAMO MAPUTO (rebels) and FRELIMO (state forces) • RENAMO received security guarantees and a “We agree that, as prescribed in the Federation place in the state security forces while FRELIMO Constitution, the Cantonal governments shall maintained elements of control (Manning 2002). ensure that the composition of the police shall • RENAMO combatants transferring to the joint reect that of the population, according to the military were allowed to keep their rank even if the 1991 census, provided that the composition of had not received the training commensurate with the police of each Municipality, shall reect the that position. -

3 Quelimane 3.1 Scope and Methods of the Cost

Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized MOZAMBIQUE Public Disclosure Authorized UPSCALING NATURE-BASED FLOOD PROTECTION IN MOZAMBIQUE’S CITIES Cost-Benefit Analyses for Potential Nature-Based Solutions in Nacala and Quelimane January 2020 Public Disclosure Authorized Project Client: World Bank (WB) Project: Consultancy Services for Upscaling Nature-Based Flood Protection in Mozambique’s Cities (Selection No. 1254774) Document Title: Task 3 – Cost-Benefit Analyses for Potential Nature-Based Solutions in Nacala and Quelimane Cover photo by: IL/CES Handling and document control Prepared by CES Consulting Engineers Salzgitter GmbH and Inros Lackner SE (Team Leader: Matthias Fritz, CES) Quality control and review by World Bank Task Team: Bontje Marie Zangerling (Task Team Lead), Brenden Jongman, Michel Matera, Lorenzo Carrera, Xavier Agostinho Chavana, Steven Alberto Carrion, Amelia Midgley, Alvina Elisabeth Erman, Boris Ton Van Zanten, Mathijs Van Ledden Peer Reviewers: Lizmara Kirchner, João Moura Estevão Marques da Fonseca, Zuzana Stanton-Geddes, Julie Rozenberg LIST OF CONTENT 1 Introduction 10 2 Nacala 11 2.1 Scope and Methods of the Cost Benefit Analysis 11 2.1.1 Financial Analysis 12 2.1.2 Economic Analysis 12 2.2 Assumptions for Nacala City CBA 12 2.2.1 Revegetation of Land Assumptions 13 2.2.2 Combined Measures Assumptions 16 2.2.3 Benefits 18 2.3 Results 22 Financial Analysis 22 Economic Analysis 25 2.4 Results of the Base Case Scenario 26 2.5 Sensitivity Analysis 28 3 Quelimane 31 3.1 Scope and Methods of the Cost -

MOZAMBIQUE Facts, History and Geography

MOZAMBIQUE Facts, History and Geography OFFICIAL NAME República de Moçambique (Republic of Mozambique) FORM OF GOVERNMENT A multiparty republic with a single legislative house (Assembly of the Republic ) HEAD OF STATE AND GOVERNMENT President: Filipe Nyusi CAPITAL Maputo OFFICIAL LANGUAGE Portuguese MONETARY UNIT (new) metical (MTn; plural meticais) POPULATION (2018 est.) 29,824,000 POPULATION RANK (2018) 46 POPULATION PROJECTION 2030 38,381,000 TOTAL AREA (SQ MI) 308,642 TOTAL AREA (SQ KM) 799,380 1 DENSITY: PERSONS PER SQ MI (2018) 96.6 DENSITY: PERSONS PER SQ KM (2018) 37.3 URBAN-RURAL POPULATION Urban: (2018) 36% Rural: (2018) 64% LIFE EXPECTANCY AT BIRTH Male: (2016) 52 years Female: (2016) 56.2 years LITERACY: PERCENTAGE OF POPULATION AGE 15 AND OVER LITERATE Male: (2015) 70.8% Female: (2015) 43.1% GNI (U.S.$ ’000,000) (2017) 12,300 GNI PER CAPITA (U.S.$) (2017) 420 2 Introduction Mozambique, a scenic country in southeastern Africa. Mozambique is rich in natural resources, is biologically and culturally diverse, and has a tropical climate. Its extensive coastline, fronting the Mozambique Channel, which separates mainland Africa from the island of Madagascar, offers some of Africa’s best natural harbours. These have allowed Mozambique an important role in the maritime economy of the Indian Ocean, while the country’s white sand beaches are an important attraction for the growing tourism industry. Fertile soils in the northern and central areas of Mozambique have yielded a varied and abundant agriculture, and the great Zambezi River has provided ample water for irrigation and the basis for a regionally important hydroelectric power industry. -

Mozambique »

« Strengthening Cultural and Creative Industries and Inclusive Policies in Mozambique » MDG-F Culture and Development Joint Programme implemented in MOZAMBIQUE Contributions of the Joint Programme to the implementation of UNESCO’s Conventions on culture 1972 UNESCO Convention on the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage Joint Programme actions: Cultural tourism has been fostered in the World Heritage Site (WHS) of the Island of Mozambique through the establishment of 2 pilot cultural tourism tours (benefiting 72 community based tourism operators). Joint Programme products: Cultural tourism has been promoted in the World Heritage Site (WHS) of the Island of Mozambique through a large number of products linked to the establishment of the 2 pilot community-based cultural tourism tours: - Study of the Offer and Demand for Cultural Tourism in Inhambane, Nampula and Maputo City; - Findings, Recommendations & Analysis of the Study on Tourism Itineraries; - Capacity building tools: 3 training manuals related to cultural tourism, a guide for cultural tourism guides, evaluation tools and indemnity forms for cultural tourism tours; - Promotional products: brochures for cultural tourism tours, narrative and visual documentation of tangible and intangible cultural assets for cultural tourism tours in Inhambane and Mozambique Island. 2003 UNESCO Convention on the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage Joint Programme actions: Gender equality and poverty eradication have been supported through income and employment generation linked to intangible cultural heritage, particularly for women, following the establishment of 4 new cultural tourism tours showcasing local cultural heritage (employment opportunities linked to oral traditions and expressions (storytelling), performing arts (dance groups), social practices (gastronomy) etc.); Intangible cultural heritage supporting maternal health, health education, and the fight against HIV/AIDS (e.g. -

Archaeological and Historical Reconstructions of the Foraging and Farming Communities of the Lower Zambezi: from the Mid-Holocene to the Second Millennium AD

Hilário Madiquida Archaeological and Historical Reconstructions of the Foraging and Farming Communities of the Lower Zambezi: From the mid-Holocene to the second Millennium AD Department of Archaeology and Ancient History Uppsala 2015 Dissertation presented at Uppsala University to be publicly examined in Eng/2-0076, Uppsala, Wednesday, 2 December 2015 at 10:15 for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. The examination will be conducted in English. Faculty examiner: Senior Lecturer Dr Munyaradzi Manyanga (Department of History, University of Zimbabwe). Abstract Madiquida, H. 2015. Archaeological and Historical Reconstructions of the Foraging and Farming Communities of the Lower Zambezi. From the mid Holocene to the second Millennium AD. 198 pp. Uppsala: Department of Archaeology and Ancient History. ISBN 978-91-506-2488-5. In this thesis I combine new archaeological surveys and excavations together with the historical and ethnographic sources, to construct a long term settlement history and historical ecology of the lower Zambezi River valley and delta region, in Mozambique. The evidence presented indicates that people have settled in the area since the Late Stone Age, in total eight new archaeological sites have been located in archaeological surveys. Two sites have been excavated in the course of this thesis work, Lumbi and Sena, each representing different chronological phases. Lumbi has a continuous settlement from the Late Stone Age (LSA) to Early Farming Communities (EFC). In this thesis I suggest that Lumbi represents a phase of consolidation which resulted in the amalgamation of LSA communities into the EFC complex around the first centuries AD. Meanwhile, Sena has evidence of both EFC and Late Farming Community (LFC) occupation. -

The Development of Nationalism in Mozambique

The development of nationalism in Mozambique http://www.aluka.org/action/showMetadata?doi=10.5555/AL.SFF.DOCUMENT.CHILCO166 Use of the Aluka digital library is subject to Aluka’s Terms and Conditions, available at http://www.aluka.org/page/about/termsConditions.jsp. By using Aluka, you agree that you have read and will abide by the Terms and Conditions. Among other things, the Terms and Conditions provide that the content in the Aluka digital library is only for personal, non-commercial use by authorized users of Aluka in connection with research, scholarship, and education. The content in the Aluka digital library is subject to copyright, with the exception of certain governmental works and very old materials that may be in the public domain under applicable law. Permission must be sought from Aluka and/or the applicable copyright holder in connection with any duplication or distribution of these materials where required by applicable law. Aluka is a not-for-profit initiative dedicated to creating and preserving a digital archive of materials about and from the developing world. For more information about Aluka, please see http://www.aluka.org The development of nationalism in Mozambique Author/Creator Mondlane, Eduardo Date 1964-12-03 Resource type Essays Language English Subject Coverage (spatial) Mozambique Coverage (temporal) 1939-1964 Source University of Southern California, University Archives Description Essay about the development of nationalism in Mozambique. Format extent 11 page(s) (length/size) http://www.aluka.org/action/showMetadata?doi=10.5555/AL.SFF.DOCUMENT.CHILCO166 http://www.aluka.org (mu ýpz4me/y± 4 (fl oÜrffý i'n " (mu ýpz4me/y± 4 (fl oÜrffý i'n " THE LEVELOPMENT OF NATIONALISM IN M IUE 2 Mozambican nationalism, like practically all african nationalism, was born out of direct European colonialism. -

Lessons from Mozambique: the Maputo Water Concession Contract

Lessons from Mozambique: The Maputo Water Concession Contract LESSONS FROM MOZAMBIQUE: THE MAPUTO WATER CONCESSION By Horácio Zandamela Page TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 LIST OF TABLES 2 ABBREVIATIONS 3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 4 INTRODUCTION 8 THE SOCIO-POLITICAL AND ECONOMIC CONTEXT 8 General Information 8 The Urban Scenario 8 The Colonial Legacy 9 The Options for Mozambique after Independence 10 Mozambique and the Future 11 THE PRIVATISATION PROCESS IN MOZAMBIQUE 12 General Aspects 12 The Water Contracts 13 The Outcomes of the Water Contracts 21 The Labour Issue 27 The Environmental Issue 29 The Risks 30 CONCLUSIONS 30 REFERENCES 33 1 Lessons from Mozambique: The Maputo Water Concession Contract LIST OF TABLES Table 1: Participants in the Pre-Qualification Bid Table 2: Capital Stock Breakdown of AdM Table 3: List of Current Contracts for Water Supply in Maputo Table 4: Settlements Inside Maputo Area Table 5: Settlements Inside Matola City Table 6: Number of New Connections Table 7: Percentage of Improper Water in Maputo Table 8: Tariffs Structures in Maputo Table 9: Operator Tariff Schedule for Maputo Table 10: New Tariff Adjustment Table 11: Staff Profile 2 Lessons from Mozambique: The Maputo Water Concession Contract ABBREVIATIONS AdM Aguas de Moçambique BAs Beneficiary Assessments CRA Council for the Regulation of Water Supply DNA National Directorate of Water ESAF Enhanced Structural Adjustment Facility FAO Food Agricultural Organisation FIPAG Asset and Investment Water Fund GOM Government of Mozambique IDA International Development Agency IMF