Lessons from Mozambique: the Maputo Water Concession Contract

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Humanitarian Service Medal - Approved Operations Current As Of: 16 July 2021

Humanitarian Service Medal - Approved Operations Current as of: 16 July 2021 Operation Start Date End Date Geographic Area1 Honduras, guatamala, Belize, El Salvador, Costa Rica, Dominican Republic, Hurricanes Eta and Iota 5-Nov-20 5-Dec-20 Nicaragua, Panama, and Columbia, adjacent airspace and adjacent waters within 10 nautical miles Port of Beirut Explosion Relief 4-Aug-20 21-Aug-20 Beirut, Lebanon DoD Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) 31-Jan-20 TBD Global Operations / Activities Military personnel who were physically Australian Bushfires Contingency Operations 1-Sep-19 31-Mar-20 present in Australia, and provided and Operation BUSHFIRE ASSIST humanitarian assistance Cities of Maputo, Quelimane, Chimoio, Tropical Cyclone Idai 23-Mar-19 13-Apr-19 and Beira, Mozambique Guam and U.S. Commonwealth of Typhoon Mangkhut and Super Typhoon Yutu 11-Sep-18 2-Feb-19 Northern Mariana Islands Designated counties in North Carolina and Hurricane Florence 7-Sep-18 8-Oct-18 South Carolina California Wild Land Fires 10-Aug-18 6-Sep-18 California Operation WILD BOAR (Tham Luang Nang 26-Jun-18 14-Jul-18 Thailand, Chiang Rai Region Non Cave rescue operation) Tropical Cyclone Gita 11-Feb-18 2-May-18 American Samoa Florida; Caribbean, and adjacent waters, Hurricanes Irma and Maria 8-Sep-17 15-Nov-17 from Barbados northward to Anguilla, and then westward to the Florida Straits Hurricane Harvey TX counties: Aransas, Austin, Bastrop, Bee, Brazoria, Calhoun, Chambers, Colorado, DeWitt, Fayette, Fort Bend, Galveston, Goliad, Gonzales, Hardin, Harris, Jackson, Jasper, Jefferson, Karnes, Kleberg, Lavaca, Lee, Liberty, Matagorda, Montgomery, Newton, 23-Aug-17 31-Oct-17 Texas and Louisiana Nueces, Orange, Polk, Refugio, Sabine, San Jacinto, San Patricio, Tyler, Victoria, Waller, and Wharton. -

Mozambique Zambia South Africa Zimbabwe Tanzania

UNITED NATIONS MOZAMBIQUE Geospatial 30°E 35°E 40°E L a k UNITED REPUBLIC OF 10°S e 10°S Chinsali M a l a w TANZANIA Palma i Mocimboa da Praia R ovuma Mueda ^! Lua Mecula pu la ZAMBIA L a Quissanga k e NIASSA N Metangula y CABO DELGADO a Chiconono DEM. REP. OF s a Ancuabe Pemba THE CONGO Lichinga Montepuez Marrupa Chipata MALAWI Maúa Lilongwe Namuno Namapa a ^! gw n Mandimba Memba a io u Vila úr L L Mecubúri Nacala Kabwe Gamito Cuamba Vila Ribáué MecontaMonapo Mossuril Fingoè FurancungoCoutinho ^! Nampula 15°S Vila ^! 15°S Lago de NAMPULA TETE Junqueiro ^! Lusaka ZumboCahora Bassa Murrupula Mogincual K Nametil o afu ezi Namarrói Erego e b Mágoè Tete GiléL am i Z Moatize Milange g Angoche Lugela o Z n l a h m a bez e i ZAMBEZIA Vila n azoe Changara da Moma n M a Lake Chemba Morrumbala Maganja Bindura Guro h Kariba Pebane C Namacurra e Chinhoyi Harare Vila Quelimane u ^! Fontes iq Marondera Mopeia Marromeu b am Inhaminga Velha oz P M úngu Chinde Be ni n è SOFALA t of ManicaChimoio o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o gh ZIMBABWE o Bi Mutare Sussundenga Dondo Gweru Masvingo Beira I NDI A N Bulawayo Chibabava 20°S 20°S Espungabera Nova OCE A N Mambone Gwanda MANICA e Sav Inhassôro Vilanculos Chicualacuala Mabote Mapai INHAMBANE Lim Massinga p o p GAZA o Morrumbene Homoíne Massingir Panda ^! National capital SOUTH Inhambane Administrative capital Polokwane Guijá Inharrime Town, village o Chibuto Major airport Magude MaciaManjacazeQuissico International boundary AFRICA Administrative boundary MAPUTO Xai-Xai 25°S Nelspruit Main road 25°S Moamba Manhiça Railway Pretoria MatolaMaputo ^! ^! 0 100 200km Mbabane^!Namaacha Boane 0 50 100mi !\ Bela Johannesburg Lobamba Vista ESWATINI Map No. -

Delegated Management of Urban Water Supply Services in MOZAMBIQUE

DELEGATED MANAGEMENT OF URBAN WATER SUPPLY SERVICES IN MOZAMBIQUE SUMMARY OF THE CASE STUDY OF FIPAG & CRA Delegated management of urban water supply services in Mozambique encountered a string of difficulties soon after it was introduced in 1999, but in 2007 a case study revealed that most problems had been overcome and the foundations for sustainability had been established. The government’s strong commitment, the soundness of the institutional reform and the quality of sector leadership can be credited for these positive results. Donor support for investments and institutional development were also important. Results reported here are as of the end of 2007. hen the prolonged civil war in Mozambique ended in exacerbated by the floods of 2000 and delays in the 1992, water supply infrastructure had deteriorated. implementation of new investments – and in December 2001 WIn 1998, the Government adopted a comprehensive SAUR terminated its involvement. Subsequently FIPAG and AdeM’s institutional reform for the development, delivery and regulation remaining partners led by Águas de Portugal (AdeP) renegotiated of urban water supply services in large cities. The new framework, the contracts, introducing higher fees and improvements in the known as the Delegated Management Framework (DMF), was specification of service obligations and procedures. The Revised inaugurated with the creation of two autonomous public bodies: Lease Contract became effective in April 2004, and will terminate an asset management agency (FIPAG) and an independent on November 30, 2014, fifteen years after the starting date of regulator (CRA). the Original Lease Contract. A new Management Contract for the period April 2004 – March 2007 consolidated the four Lease and Management Contracts with Águas de Original Management Contracts. -

Accelerating the Implementation of Commitments to African Women

DIRECTORATE OF INFORMATION & COMMUNICATION Press Release No: /2020 Date: 18 Nov 2020 Venue: Addis ABaBa, Ethiopia Slow progress in meeting commitment to 2020 as the year of universal ratification of Maputo protocol A two-day meeting convened to evaluate the status of the ratification, domestication and implementation of the Protocol to the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights on the Rights of Women in Africa, commonly referred to as the Maputo Protocol on Women’s Rights, has concluded with strong recommendations on how to accelerate actions on the commitment to African women. Described as a vanguard document at the time of its adoption in 2003, the Maputo Protocol remains one of the most progressive legal instruments providing a comprehensive set of human rights for African women. It translates Africa’s commitment to invest in the development and empowerment of women and girls, who constitute the majority constituent of the population. Convened by the African Union Commission Women, Gender and Development Directorate in collaboration with and the Gender, Peace and Security Programme of the AUC Peace and Security Department and the Solidarity for African Women’s Rights the meetings held on the 17-18 November 2020 brought together African Union Experts responsible for Gender Equality and Women’s Affairs; the Pan-African Parliament; Civil Society Organizations, women’s rights organizations, women’s movements and youth organizations to evaluate the progress achieved especially at the national level, in protecting and promoting the rights of women as encapsulated in the Protocol. In deliberating on the advancement of women’s rights, the meeting noted that across the continent, a number of countries have enacted laws against sexual and gender based violence as well as harmful cultural practices while others have established dedicated national machineries to promote and protect the rights of women. -

Strategic Action Programme for the Protection of The

First published in Kenya in 2009 by the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP)/Nairobi Convention Secretariat. Copyright © 2009, UNEP/Nairobi Convention Secretariat. This publication may be reproduced in whole or in part and in any form for educational or non-profit purposes without special permission from the copyright holder provided that acknowledgement of the source is made. UNEP/Nairobi Convention Secretariat would appreciate receiving a copy of any publication that uses this publication as a source. No use of this publication may be made for resale or for any other commercial purpose without prior permission in writing from UNEP/Nairobi Convention Secretariat. UNEP/Nairobi Convention Secretariat United Nations Environment Programme United Nations Avenue, Gigiri, P.O Box 47074, Nairobi, Kenya Tel: +254 (0)20 7621250/2025/1270 Fax: +254 (0)20 7623203 Email: [email protected] Thematic Authors: Prof. Rudy Van Der Elst, Prof. George Khroda, Prof. Mwakio Tole, Prof. Jan Glazewski and Ms. Amanda Younge-Hayes Editors: Dr. Peter Scheren, Dr. Johnson Kitheka and Ms. Daisy Ouya For citation purposes this document may be cited as: UNEP/Nairobi Convention Secretariat, 2009. Strategic Action Programme for the Protection of the Coastal and Marine Environment of the Western Indian Ocean from Land-based Sources and Activities, Nairobi, Kenya, 140 pp. Disclaimer: This document was prepared within the framework of the Nairobi Convention in consultation with its 10 Contracting Parties, namely the Governments of Comoros, France (La Réunion), -

Maputo, Mozambique Casenote

Transforming Urban Transport – The Role of Political Leadership TUT-POL Sub-Saharan Africa Final Report October 2019 Case Note: Maputo, Mozambique Lead Author: Henna Mahmood Harvard University Graduate School of Design 1 Acknowledgments This research was conducted with the support of the Volvo Foundation for Research and Education. Principal Investigator: Diane Davis Senior Research Associate: Lily Song Research Coordinator: Devanne Brookins Research Assistants: Asad Jan, Stefano Trevisan, Henna Mahmood, Sarah Zou 2 MAPUTO, MOZAMBIQUE MOZAMBIQUE Population: 27,233,789 (as of July 2018) Population Growth Rate: 2.46% (2018) Median Age: 17.3 GDP: USD$37.09 billion (2017) GDP Per Capita: USD$1,300 (2017) City of Intervention: Maputo Urban Population: 36% of total population (2018) Urbanization Rate: 4.35% annual rate of change (2015-2020 est.) Land Area: 799,380 sq km Roadways: 31,083 km (2015) Paved Roadways: 7365 km (2015) Unpaved Roadways: 23,718 km (2015) Source: CIA Factbook I. POLITICS & GOVERNANCE A. Multi- Scalar Governance Sixteen years following Mozambique’s independence in 1975 and civil war (1975-1992), the government of Mozambique began to decentralize. The Minister of State Administration pushed for greater citizen involvement at local levels of government. Expanding citizen engagement led to the question of what role traditional leaders, or chiefs who wield strong community influence, would play in local governance.1 Last year, President Filipe Nyusi announced plans to change the constitution and to give political parties more power in the provinces. The Ministry of State Administration and Public Administration are also progressively implementing a decentralization process aimed at transferring the central government’s political and financial responsibilities to municipalities (Laws 2/97, 7-10/97, and 11/97).2 An elected Municipal Council (composed of a Mayor, a Municipal Councilor, and 12 Municipal Directorates) and Municipal Assembly are the main governing bodies of Maputo. -

Transition Towards Green Growth in Mozambique

GREEN GROWTH MOZAMBIQUE POLICY REVIEW AND RECOMMENDATIONS FOR ACTION Transition Towards Green Growth in Mozambique and 2015 - 2015 All rights reserved. Printed in Côte d’Ivoire, designed by MZ in Tunisia - 2015 This knowledge product is part of the work undertaken by the African Development Bank in the context of its new Strategy 2013-2022, whose twin objectives are “inclusive and increasingly green growth”. The Bank provides technical assistance to its regional member countries for embarking on a green growth pathway. Mozambique is one of these countries. The Bank team is grateful to the Government of Mozambique, national counterparts, World Wildlife Fund (WWF), United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) and United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) for participating in the preparation and review of this report. Without them, this work would not have been possible. We acknowledge the country’s collective efforts to mainstream green growth into the new National Development Strategy and to build a more sustainable development model that benefits all Mozambicans, while preserving the country’s natural capital. A team from the African Development Bank, co-led by Joao Duarte Cunha (ONEC) and Andre Almeida Santos (MZFO), prepared this report with the support of Eoin Sinnot, Prof. Almeida Sitoe and Ilmi Granoff as consultants. Key sector inputs were provided by a multi-sector team comprised of Yogesh Vyas (CCCC), Jean-Louis Kromer and Cesar Tique (OSAN), Cecile Ambert (OPSM), Aymen Ali (OITC) and Boniface Aleboua (OWAS). Additional review and comments were provided by Frank Sperling and Florence Richard (ONEC) of the Bank-wide Green Growth team, as well as Emilio Dava (MZFO) and Josef Loening (TZFO). -

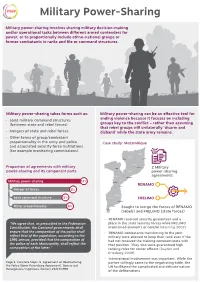

Military Power-Sharing

Military Power-Sharing Military power-sharing involves sharing military decision-making and/or operational tasks between dierent armed contenders for power; or to proportionally include ethno-national groups or former combatants in ranks and file or command structures. Military power-sharing takes forms such as: Military power-sharing can be an eective tool for • Joint military command structures ending violence because it focuses on including (between state and rebel forces) groups key to the conflict – rather than assuming that rebel groups will unilaterally ‘disarm and • Mergers of state and rebel forces disband’ while the state army remains. • Other forms of group/combatant proportionality in the army and police Case study: Mozambique and associated security force institutions (for example monitoring commissions). CABO DELGADO NIASSA LICHINGA PEMBA NAMPULA TETE NAMPULA Proportion of agreements with military TETE 2 Military power-sharing and its component parts ZAMBEZIA power-sharing MANICA agreements QUELIMANE SOFALA Military power-sharing 13% CHIMOIO BEIRA RENAMO Merger of forces 8% INHAMBANE Joint command structure 5% GAZA FRELIMO INHAMBANE Other proportionality 6% XAI-XAI Sought to merge the forces of RENAMO MAPUTO (rebels) and FRELIMO (state forces) • RENAMO received security guarantees and a “We agree that, as prescribed in the Federation place in the state security forces while FRELIMO Constitution, the Cantonal governments shall maintained elements of control (Manning 2002). ensure that the composition of the police shall • RENAMO combatants transferring to the joint reect that of the population, according to the military were allowed to keep their rank even if the 1991 census, provided that the composition of had not received the training commensurate with the police of each Municipality, shall reect the that position. -

Sub-Saharan African Tripartite Workshop on Occupational Safety

INTERNATIONAL LABOUR ORGANIZATION Sub -Saharan African Tripartite Workshop on Occupational Safety and Health in the Oil and Gas Maputo Industry 17-18 May 2017 Points of Consensus Introduction 1. The ILO sub-Saharan African Workshop on Occupational Safety and Health (OSH) in the Oil and Gas Industry brought together tripartite delegations from Angola, Cameroon, Cote d’Ivoire, Gabon, Kenya, Mozambique and Nigeria and observers from the IndustriALL Global Union. The purpose of the workshop was to discuss and exchange good practices of improving OSH and to promote a preventative safety and health culture in the oil and gas industry in sub-Saharan African countries. Risks and challenges for workers’ safety and health in sub-Saharan Africa 2. The oil and gas industry is an important driver of economic growth in sub-Saharan African countries. Existing physical, biological, chemical and ergonomic hazards in the oil and gas industry are compounded by unfavourable climatic factors, which leads to heat stress that in turn increases the risk of workplace injuries and diseases. Psychosocial problems may result from working in remote base camps or on offshore drilling platforms for extended periods of time. Transportation to and from these sites can be extremely hazardous, especially if operations are located in or near conflict-affected areas. Excessive working hours and irregular working time arrangements have a negative effect on workers’ health, alertness and performance. 3. Consequently, a number of occupational fatalities, injuries and diseases have been reported yearly. In the absence of effective monitoring and reporting systems, the actual number of accidents and incidents is not known, but suspected to be higher. -

Applying a Methodology of Production Potential Based on the Type of Soil and Climate: Mozambique

The 22nd International Symposium on Alcohol Fuels – 22nd ISAF Applying a methodology of production potential based on the type of soil and climate: Mozambique Felipe Haenel Gomesa*, Rafael Aldighieri Moraesb, Edgar G. F. de Beauclairc a: Universidade Estadual de Maringá, PR, Brasil, [email protected] b: Nucleo Interdisciplinar de Planejamento Energético (NIPE), campus UNICAMP, Campinas, SP, Brasil, [email protected] c: Universidade de São Paulo, ESALQ, 13.418-900, Piracicaba, SP, Brasil, [email protected] Abstract The diversity of soil and climatic types existing in Mozambique involves a wide range of potential and land use limitations. The methodology used is based in Brazilian soil taxonomic system of classification and comparison between soil type and sugarcane productivity with a method developed by CTC – Sugarcane Technology Center where soil classes were subdivided into different types according to its characteristics, concepts and taxonomic criteria used in classification and based on commercial productivity of its databank with more than a hundred mills. Then, Brazilian System of Soil Classification were correlated with the |International Soil Classification System WRB-FAO. For climate characteristics, Köppen classification adapted was used. It consists in main types, which are represented by the letters A, B, C, D and E. These climatic types are defined criteria for temperature and rainfall. The objective was to draw up a map of potential production of sugarcane in Mozambique, using as basic information: soil, climate and areas with environmental restrictions. It was found that the regions with high and medium potential were the provinces located in the northern and central Mozambique, even using irrigation, due to the soil potential of these regions. -

3 Quelimane 3.1 Scope and Methods of the Cost

Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized MOZAMBIQUE Public Disclosure Authorized UPSCALING NATURE-BASED FLOOD PROTECTION IN MOZAMBIQUE’S CITIES Cost-Benefit Analyses for Potential Nature-Based Solutions in Nacala and Quelimane January 2020 Public Disclosure Authorized Project Client: World Bank (WB) Project: Consultancy Services for Upscaling Nature-Based Flood Protection in Mozambique’s Cities (Selection No. 1254774) Document Title: Task 3 – Cost-Benefit Analyses for Potential Nature-Based Solutions in Nacala and Quelimane Cover photo by: IL/CES Handling and document control Prepared by CES Consulting Engineers Salzgitter GmbH and Inros Lackner SE (Team Leader: Matthias Fritz, CES) Quality control and review by World Bank Task Team: Bontje Marie Zangerling (Task Team Lead), Brenden Jongman, Michel Matera, Lorenzo Carrera, Xavier Agostinho Chavana, Steven Alberto Carrion, Amelia Midgley, Alvina Elisabeth Erman, Boris Ton Van Zanten, Mathijs Van Ledden Peer Reviewers: Lizmara Kirchner, João Moura Estevão Marques da Fonseca, Zuzana Stanton-Geddes, Julie Rozenberg LIST OF CONTENT 1 Introduction 10 2 Nacala 11 2.1 Scope and Methods of the Cost Benefit Analysis 11 2.1.1 Financial Analysis 12 2.1.2 Economic Analysis 12 2.2 Assumptions for Nacala City CBA 12 2.2.1 Revegetation of Land Assumptions 13 2.2.2 Combined Measures Assumptions 16 2.2.3 Benefits 18 2.3 Results 22 Financial Analysis 22 Economic Analysis 25 2.4 Results of the Base Case Scenario 26 2.5 Sensitivity Analysis 28 3 Quelimane 31 3.1 Scope and Methods of the Cost -

Highlights Situation Overview

Mozambique: Flooding Office of the Resident Coordinator, Situation Report No. 5 (As of 13 March 2015) This report is prepared by the Humanitarian Country Team/Office of the Resident Coordinator in Mozambique. It covers the period from 24 February to 13 March 2015. Highlights From 04 to 08 March 2015, the central and north of the country were severely affected by heavy rains due to a tropical depression formed in the Mozambique Channel affecting at least 144,882 people in Nampula and Cabo Delgado; There are about 10,000 houses destroyed partially/completely in Nampula and Cabo Delgado; In Zambézia province, in terms of Agriculture, there are 60,723 households affected and 60,051 ha of crops lost; A cholera outbreak has been confirmed in Tete, Nampula, Zambézia, Sofala and Niassa provinces, with a cumulative of 5.894 cases and 48 deaths since 25 December 2014. Flooded area in Nampula province, Larde district – March 2015 © INGC Mozambique 327,327 163 56,259 US$ 20,9 5.894 Affected people Deaths people in million Cholera cases in Tete, accommodation Nampula, Sofala, Needed for ongoing centers/resettlement Response and Recovery Zambézia and Niassa centers actions Situation Overview The Mozambican government on 3rd March 2015 downgraded the state of alert from red to orange, following a general improvement in the weather and the receding of floodwaters in the central and northern provinces. Furthermore, the government had opted to downgrade the alert, because life in the flood-affected areas has been gradually returning to normal. Regardless the downgrade of the red alert, all actions to support people affected by the floods in Zambézia would continue and tied vigilance on the climatic conditions as we still in the rainy and cyclone season.