On Musical Self-Similarity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2021 V. 55 № 1/1 Special Issue the Organizers

ISSN 0233-528X Aerospace and Environmental Medicine 2021 V. 55 № 1/1 special issue The Organizers: INTERNATIONAL ACADEMY OF ASTRONAUTICS (IAA) STATE SPACE CORPORATION “ROSCOSMOS” MINISTRY OF SCIENCE AND HIGHER EDUCATION OF THE RUSSIAN FEDERATION RUSSIAN ACADEMY OF SCIENCES (RAS) STATE RESEARCH CENTER OF THE RUSSIAN FEDERATION – INSTITUTE OF BIOMEDICAL PROBLEMS RAS Aerospace and Environmental Medicine AVIAKOSMICHESKAYA I EKOLOGICHESKAYA MEDITSINA SCIENTIFIC JOURNAL EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Orlov O.I., M.D., Academician of RAS EDITORIAL BOARD The Organizers: Ardashev V.N., M.D., professor Baranov V.M., M.D., professor, Academician of RAS Buravkova L.B., M.D., professor, Corresponding Member of RAS Bukhtiyarov I.V., M.D., professor Vinogradova O.L., Sci.D., professor – Deputy Editor D’yachenko A.I., Tech. D., professor Ivanov I.V., M.D., professor Ilyin E.A., M.D., professor Kotov O.V., Ph.D. Krasavin E.A., Ph.D., Sci.D., professor, Corresponding Member of RAS Medenkov A.A., Ph.D. in Psychology, M.D., professor Sinyak YU.E., M.D., Tech.D., professor Sorokin O.G., Ph.D. Suvorov A.V., M.D., professor Usov V.M., M.D., professor Homenko M.N., M.D., professor Mukai Ch., M.D., Ph.D. (Japan) Sutton J., M.D., Ph.D. (USA) Suchet L.G., Ph.D. (France) ADVISORY BOARD Grigoriev A.I., M.D., professor, Academician of RAS, Сhairman Blaginin A.A., M.D., Doctor of Psychology, professor Gal’chenko V.F., Sci.D., professor, Corresponding Member of RAS Zhdan’ko I.M., M.D. Ostrovskij M.A., Sci.D., professor, Academician of RAS Rozanov A.YU., D.Geol.Mineral.S., professor, Academician of RAS Rubin A.B., Sci.D., professor, Corresponding Member of RAS Zaluckij I.V., Sci.D., professor, Corresponding Member of NASB (Belarus) Kryshtal’ O.A., Sci.D., professor, Academician of NASU (Ukraine) Makashev E.K., D.Biol.Sci., professor, Corresponding Member of ASRK (Kazakhstan) Gerzer R., M.D., Ph.D., professor (Germany) Gharib C., Ph.D., professor (France) Yinghui Li, M.D., Ph.D., professor (China) 2021 V. -

A Theory of Spatial Acquisition in Twelve-Tone Serial Music

A Theory of Spatial Acquisition in Twelve-Tone Serial Music Ph.D. Dissertation submitted to the University of Cincinnati College-Conservatory of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Ph.D. in Music Theory by Michael Kelly 1615 Elkton Pl. Cincinnati, OH 45224 [email protected] B.M. in Music Education, the University of Cincinnati College-Conservatory of Music B.M. in Composition, the University of Cincinnati College-Conservatory of Music M.M. in Music Theory, the University of Cincinnati College-Conservatory of Music Committee: Dr. Miguel Roig-Francoli, Dr. David Carson Berry, Dr. Steven Cahn Abstract This study introduces the concept of spatial acquisition and demonstrates its applicability to the analysis of twelve-tone music. This concept was inspired by Krzysztof Penderecki’s dis- tinctly spatial approach to twelve-tone composition in his Passion According to St. Luke. In the most basic terms, the theory of spatial acquisition is based on an understanding of the cycle of twelve pitch classes as contiguous units rather than discrete points. Utilizing this theory, one can track the gradual acquisition of pitch-class space by a twelve-tone row as each of its member pitch classes appears in succession, noting the patterns that the pitch classes exhibit in the pro- cess in terms of directionality, the creation and filling in of gaps, and the like. The first part of this study is an explanation of spatial acquisition theory, while the se- cond part comprises analyses covering portions of seven varied twelve-tone works. The result of these analyses is a deeper understanding of each twelve-tone row’s composition and how each row’s spatial characteristics are manifested on the musical surface. -

Joint Session: Measuring Fractals Diversity in Mathematics, 2019

Joint Session: Measuring Fractals Diversity in Mathematics, 2019 Tongou Yang The University of British Columbia, Vancouver [email protected] July 2019 Tongou Yang (UBC) Fractal Lectures July 2019 1 / 12 Let's Talk Geography Which country has the longest coastline? What is the longest river on earth? Tongou Yang (UBC) Fractal Lectures July 2019 2 / 12 (a) Map of Canada (b) Map of Nunavut Which country has the longest coastline? List of countries by length of coastline Tongou Yang (UBC) Fractal Lectures July 2019 3 / 12 (b) Map of Nunavut Which country has the longest coastline? List of countries by length of coastline (a) Map of Canada Tongou Yang (UBC) Fractal Lectures July 2019 3 / 12 Which country has the longest coastline? List of countries by length of coastline (a) Map of Canada (b) Map of Nunavut Tongou Yang (UBC) Fractal Lectures July 2019 3 / 12 What's the Longest River on Earth? A Youtube Video Tongou Yang (UBC) Fractal Lectures July 2019 4 / 12 Measuring a Smooth Curve Example: use a rope Figure: Boundary between CA and US on the Great Lakes Tongou Yang (UBC) Fractal Lectures July 2019 5 / 12 Measuring a Rugged Coastline Figure: Coast of Nova Scotia Tongou Yang (UBC) Fractal Lectures July 2019 6 / 12 Covering by Grids 4 3 2 1 0 0 1 2 3 4 Tongou Yang (UBC) Fractal Lectures July 2019 7 / 12 Counting Grids Number of Grids=15 Side Length ≈ 125km Coastline ≈ 15 × 125 = 1845km. Tongou Yang (UBC) Fractal Lectures July 2019 8 / 12 Covering by Finer Grids 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 0 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Tongou Yang (UBC) Fractal Lectures July 2019 9 / 12 Counting Grids Number of Grids=34 Side Length ≈ 62km Coastline ≈ 34 × 62 = 2108km. -

% ^JJV^/W^K Sar^Fcsj^

% ^JJV^/W^K Sar^fcsj^ sm il 1 » STELLINGEN 1. In de buitenste delen van ^piraalstelsels zijn de rotafiefrequentie, de epicycle- frequentie, en de oscillatiefrequentie Jie de beweging loodrecht op het sym- metrievlak karakteriseert, nagenoeg gelijk. Een eenmaal ontstane asym- metrische afwijking van de gasverdeling ten opzichte van het symmetnevlak (warping) kan zich daarom in de buitenste delen van een spiraalstelsel gedurende lange tijd handhaven. 2. De suggestie dat door resonante effecten bij de binnenste Lindbiad resonantie balkachtige structuren kunnen ontstaan berust vooralsnog op wishful thinkmg. J. W. K. Mark. 1974. in The formation and dynamics of galaxies. I. A. U. Symp. 5B. Hd. Shakeshaft. J. R. (Reidel. Dordrecht). 3. Het is moeilijk een fysische betekenis toe te kennen aan kinematische modellen gebaseerd op dispersieringen, als die modellen worden toegepast op waar- nemingen in de buurt van de binnenste Lindbiad resonantie. S. C. Simonson and G. L. Mader, 1973. Astron. Astrophysics. 27. 33". R. B. Tully. thesis, University of Maryland. 1972. 4. In publicaties van waarnemingen van de verdeling en kinematica van neutrale waterstof in extragalactische stelsels dient naast het afgeleide snelheidsveld ook een efficiënte presentatie te worden gegeven van de gemeten lijnprofielen. A. H. Rots. dissertatie, Rijksuniversiteit Groningen, 1974 5. De bewering van Fernie dat Huggins in 1865 door een foutieve interpretatie van zijn gegevens tot de conclusie kwam dat nevels gasvormig zijn, is onjuist. J. D. Fernie. 1970. Pub. A. S. P. 82, 1189. 6. De toenemende mogenlijkheden om de weersomstandigheden te beinvl^eden maakt spoedig internationaal overleg gewenst om vast te leggen binnen welke grenzen deze beinvloeding toela2tba-: is en om de rechtspositie van door veranderde klimatologische condities getroffen personen vast te stellen. -

The Development of Hierarchical Knowledge in Robot Systems

THE DEVELOPMENT OF HIERARCHICAL KNOWLEDGE IN ROBOT SYSTEMS A Dissertation Presented by STEPHEN W. HART Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY September 2009 Computer Science c Copyright by Stephen W. Hart 2009 All Rights Reserved THE DEVELOPMENT OF HIERARCHICAL KNOWLEDGE IN ROBOT SYSTEMS A Dissertation Presented by STEPHEN W. HART Approved as to style and content by: Roderic Grupen, Chair Andrew Barto, Member David Jensen, Member Rachel Keen, Member Andrew Barto, Department Chair Computer Science To R. Daneel Olivaw. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This dissertation would not have been possible without the help and support of many people. Most of all, I would like to extend my gratitude to Rod Grupen for many years of inspiring work, our discussions, and his guidance. Without his sup- port and vision, I cannot imagine that the journey would have been as enormously enjoyable and rewarding as it turned out to be. I am very excited about what we discovered during my time at UMass, but there is much more to be done. I look forward to what comes next! In addition to providing professional inspiration, Rod was a great person to work with and for|creating a warm and encouraging labora- tory atmosphere, motivating us to stay in shape for his annual half-marathons, and ensuring a sufficient amount of cake at the weekly lab meetings. Thanks for all your support, Rod! I am very grateful to my thesis committee|Andy Barto, David Jensen, and Rachel Keen|for many encouraging and inspirational discussions. -

WHAT USE IS MUSIC in an OCEAN of SOUND? Towards an Object-Orientated Arts Practice

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Oxford Brookes University: RADAR WHAT USE IS MUSIC IN AN OCEAN OF SOUND? Towards an object-orientated arts practice AUSTIN SHERLAW-JOHNSON OXFORD BROOKES UNIVERSITY Submitted for PhD DECEMBER 2016 Contents Declaration 5 Abstract 7 Preface 9 1 Running South in as Straight a Line as Possible 12 2.1 Running is Better than Walking 18 2.2 What You See Is What You Get 22 3 Filling (and Emptying) Musical Spaces 28 4.1 On the Superficial Reading of Art Objects 36 4.2 Exhibiting Boxes 40 5 Making Sounds Happen is More Important than Careful Listening 48 6.1 Little or No Input 59 6.2 What Use is Art if it is No Different from Life? 63 7 A Short Ride in a Fast Machine 72 Conclusion 79 Chronological List of Selected Works 82 Bibliography 84 Picture Credits 91 Declaration I declare that the work contained in this thesis has not been submitted for any other award and that it is all my own work. Name: Austin Sherlaw-Johnson Signature: Date: 23/01/18 Abstract What Use is Music in an Ocean of Sound? is a reflective statement upon a body of artistic work created over approximately five years. This work, which I will refer to as "object- orientated", was specifically carried out to find out how I might fill artistic spaces with art objects that do not rely upon expanded notions of art or music nor upon explanations as to their meaning undertaken after the fact of the moment of encounter with them. -

The Philip Glass Ensemble in Downtown New York, 1966-1976 David Allen Chapman Washington University in St

Washington University in St. Louis Washington University Open Scholarship All Theses and Dissertations (ETDs) Spring 4-27-2013 Collaboration, Presence, and Community: The Philip Glass Ensemble in Downtown New York, 1966-1976 David Allen Chapman Washington University in St. Louis Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/etd Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Chapman, David Allen, "Collaboration, Presence, and Community: The hiP lip Glass Ensemble in Downtown New York, 1966-1976" (2013). All Theses and Dissertations (ETDs). 1098. https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/etd/1098 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Theses and Dissertations (ETDs) by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY IN ST. LOUIS Department of Music Dissertation Examination Committee: Peter Schmelz, Chair Patrick Burke Pannill Camp Mary-Jean Cowell Craig Monson Paul Steinbeck Collaboration, Presence, and Community: The Philip Glass Ensemble in Downtown New York, 1966–1976 by David Allen Chapman, Jr. A dissertation presented to the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Washington University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2013 St. Louis, Missouri © Copyright 2013 by David Allen Chapman, Jr. All rights reserved. CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES .................................................................................................................... -

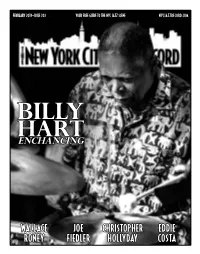

Wallace Roney Joe Fiedler Christopher

feBrUARY 2019—ISSUe 202 YOUr FREE GUide TO THE NYC JAZZ SCENE NYCJAZZRECORD.COM BILLY HART ENCHANCING wallace joe christopher eddie roney fiedler hollyday costa Managing Editor: Laurence Donohue-Greene Editorial Director & Production Manager: Andrey Henkin To Contact: The New York City Jazz Record 66 Mt. Airy Road East feBrUARY 2019—ISSUe 202 Croton-on-Hudson, NY 10520 United States Phone/Fax: 212-568-9628 new york@niGht 4 Laurence Donohue-Greene: interview : wallace roney 6 by anders griffen [email protected] Andrey Henkin: artist featUre : joe fiedler 7 by steven loewy [email protected] General Inquiries: on the cover : Billy hart 8 by jim motavalli [email protected] Advertising: encore : christopher hollyday 10 by robert bush [email protected] Calendar: lest we forGet : eddie costa 10 by mark keresman [email protected] VOXNews: LAbel spotliGht : astral spirits 11 by george grella [email protected] VOXNEWS by suzanne lorge US Subscription rates: 12 issues, $40 11 Canada Subscription rates: 12 issues, $45 International Subscription rates: 12 issues, $50 For subscription assistance, send check, cash or oBitUaries 12 by andrey henkin money order to the address above or email [email protected] FESTIVAL REPORT 13 Staff Writers Duck Baker, Stuart Broomer, Robert Bush, Kevin Canfield, CD reviews 14 Marco Cangiano, Thomas Conrad, Ken Dryden, Donald Elfman, Phil Freeman, Kurt Gottschalk, Miscellany Tom Greenland, George Grella, 31 Anders Griffen, Tyran Grillo, Alex Henderson, Robert Iannapollo, event calendar Matthew Kassel, Mark Keresman, 32 Marilyn Lester, Suzanne Lorge, Marc Medwin, Jim Motavalli, Russ Musto, John Pietaro, Joel Roberts, John Sharpe, Elliott Simon, Andrew Vélez, Scott Yanow Contributing Writers Brian Charette, Steven Loewy, As unpredictable as the flow of a jazz improvisation is the path that musicians ‘take’ (the verb Francesco Martinelli, Annie Murnighan, implies agency, which is sometimes not the case) during the course of a career. -

S:\FULLCO~1\HEARIN~1\Committee Print 2018\Henry\Jan. 9 Report

Embargoed for Media Publication / Coverage until 6:00AM EST Wednesday, January 10. 1 115TH CONGRESS " ! S. PRT. 2d Session COMMITTEE PRINT 115–21 PUTIN’S ASYMMETRIC ASSAULT ON DEMOCRACY IN RUSSIA AND EUROPE: IMPLICATIONS FOR U.S. NATIONAL SECURITY A MINORITY STAFF REPORT PREPARED FOR THE USE OF THE COMMITTEE ON FOREIGN RELATIONS UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED FIFTEENTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION JANUARY 10, 2018 Printed for the use of the Committee on Foreign Relations Available via World Wide Web: http://www.gpoaccess.gov/congress/index.html U.S. GOVERNMENT PUBLISHING OFFICE 28–110 PDF WASHINGTON : 2018 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Publishing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate Mar 15 2010 04:06 Jan 09, 2018 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5012 Sfmt 5012 S:\FULL COMMITTEE\HEARING FILES\COMMITTEE PRINT 2018\HENRY\JAN. 9 REPORT FOREI-42327 with DISTILLER seneagle Embargoed for Media Publication / Coverage until 6:00AM EST Wednesday, January 10. COMMITTEE ON FOREIGN RELATIONS BOB CORKER, Tennessee, Chairman JAMES E. RISCH, Idaho BENJAMIN L. CARDIN, Maryland MARCO RUBIO, Florida ROBERT MENENDEZ, New Jersey RON JOHNSON, Wisconsin JEANNE SHAHEEN, New Hampshire JEFF FLAKE, Arizona CHRISTOPHER A. COONS, Delaware CORY GARDNER, Colorado TOM UDALL, New Mexico TODD YOUNG, Indiana CHRISTOPHER MURPHY, Connecticut JOHN BARRASSO, Wyoming TIM KAINE, Virginia JOHNNY ISAKSON, Georgia EDWARD J. MARKEY, Massachusetts ROB PORTMAN, Ohio JEFF MERKLEY, Oregon RAND PAUL, Kentucky CORY A. BOOKER, New Jersey TODD WOMACK, Staff Director JESSICA LEWIS, Democratic Staff Director JOHN DUTTON, Chief Clerk (II) VerDate Mar 15 2010 04:06 Jan 09, 2018 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 5904 Sfmt 5904 S:\FULL COMMITTEE\HEARING FILES\COMMITTEE PRINT 2018\HENRY\JAN. -

Grade 6 Math Circles Fractals Introduction

Faculty of Mathematics Centre for Education in Waterloo, Ontario N2L 3G1 Mathematics and Computing Grade 6 Math Circles March 10/11 2020 Fractals Introduction Fractals are mathematical objects that are self-similar, meaning that they have the same structure when you zoom in on them. For example, this is a famous fractal called the Mandelbrot set: Image by Arnaud Cheritat, retrieved from: https://www.math.univ-toulouse.fr/~cheritat/wiki-draw/index.php/File:MilMand_1000iter.png 1 The main shape, which looks a bit like a snowman, is shaded in the image below: As an exercise, shade in some of the smaller snowmen that are all around the largest one in the image above. This is an example of self-similarity, and this pattern continues into infinity. Watch what happens when you zoom deeper and deeper into the Mandelbrot Set here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pCpLWbHVNhk. Drawing Fractals Fractals like the Mandelbrot Set are generated using formulas and computers, but there are a number of simple fractals that we can draw ourselves. 2 Sierpinski Triangle Image by Beojan Stanislaus, retrieved from: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Sierpinski_triangle.svg Use the template and the steps below to draw this fractal: 1. Start with an equilateral triangle. 2. Connect the midpoints of all three sides. This will create one upside down triangle and three right-side up triangles. 3. Repeat from step 1 for each of the three right-side up triangles. 3 Apollonian Gasket Retrieved from: https://mathlesstraveled.com/2016/04/20/post-without-words-6/ Use the template and the steps below to draw this fractal: 1. -

Composing Each Time Robert Morris

Composing Each Time Robert Morris Introduction Each time I finish a piece, there is little time to rest or reflect; something else demands my attention, and I attend to it. Of course, finishing a piece is not really abrupt; after the first draft, there is revision, computer engraving, and editing. During these tasks, new ideas and conceptions begin to enter consciousness so the experience of writing a particular piece fades even before all the work is done. Later, when I return to a work—to coach a performance or lecture on it—I try to reconstruct the process of composition and return to the way it felt to write it, but much of the passion and clarity that brought the work into being is lost. With some thought of addressing this problem I decided immediately after completing my piano piece Each Time to write about it while the experience of its composition was still fresh in my memory. In this way, I hope to express as vividly as possible what I try to put into a piece and how and why—something which might be useful to future performers or listeners. In some respects, Each Time is not very different from my other piano pieces; however, I wanted to express in music some new insights I had into the phenomenology of time derived from Buddhist philosophy. Rather than spelling this out now, I’ll just say that I composed the piece so it might suggest to an attentive listener that impermanence is at the root of experience and that time is both flowing and discontinuous at once. -

Prolongation, Expanding Variation, and Pitch Hierarchy: a Study of Fred Lerdahl’S Waves and Coffin Hollow

PROLONGATION, EXPANDING VARIATION, AND PITCH HIERARCHY: A STUDY OF FRED LERDAHL’S WAVES AND COFFIN HOLLOW J. Corey Knoll A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF MUSIC December 2006 Committee: Nora Engebretsen, Advisor Mikel Kuehn, Advisor William Lake Marilyn Shrude ii ABSTRACT Mikel Kuehn, Co-Advisor Nora Engebretsen, Co-Advisor This thesis consists of two independent yet interrelated portions. The theory portion explores connections between Fred Lerdahl’s theoretical and compositional output by examining his work Waves in relation to his theoretical writings, primarily A Generative Theory of Tonal Music and “Tonal Pitch Space.” The theories together form a generative theory of tonal music that strives to create a musical grammar. “Tonal Pitch Space” defines a hierarchy among pitches and chords within and across tonal regions. Lerdahl uses these ideas in Waves, which is in the key of D minor. All other pitch classes, and likewise all other chords and tonal regions, are elaborations of the tonic D. The initial D tonic statement, called a flag motive because it heralds each variation, is the fundamental construct in Waves. Just as all other pitches elaborate D, all other motives in Waves are elaborations of the flag motive. Thus rich hierarchies are established. Lerdahl also incorporates ideas from GTTM into his compositional process. GTTM focuses on four categories of event hierarchies: grouping and metrical structures and time-span and prolongational reductions. These four hierarchies and a set of stability conditions all interact with one another to form a comprehensive musical grammar.