Cholera and Venereal Disease

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cholera Transmission: the Host, Pathogen and Bacteriophage Dynamic

REVIEWS Cholera transmission: the host, pathogen and bacteriophage dynamic Eric J. Nelson*, Jason B. Harris‡§, J. Glenn Morris Jr||, Stephen B. Calderwood‡§ and Andrew Camilli* Abstract | Zimbabwe offers the most recent example of the tragedy that befalls a country and its people when cholera strikes. The 2008–2009 outbreak rapidly spread across every province and brought rates of mortality similar to those witnessed as a consequence of cholera infections a hundred years ago. In this Review we highlight the advances that will help to unravel how interactions between the host, the bacterial pathogen and the lytic bacteriophage might propel and quench cholera outbreaks in endemic settings and in emergent epidemic regions such as Zimbabwe. 15 O antigen Diarrhoeal diseases, including cholera, are the leading progenitor O1 El Tor strain . Although the O139 sero- The outermost, repeating cause of morbidity and the second most common cause group caused devastating outbreaks in the 1990s, the El oligosaccharide portion of LPS, of death among children under 5 years of age globally1,2. Tor strain remains the dominant strain globally11,16,17. which makes up the outer It is difficult to gauge the exact morbidity and mortality An extensive body of literature describes the patho- leaflet of the outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria. of cholera because the surveillance systems in many physiology of cholera. In brief, pathogenic strains har- developing countries are rudimentary, and many coun- bour key virulence factors that include cholera toxin18 Cholera toxin tries are hesitant to report cholera cases to the WHO and toxin co-regulated pilus (TCP)19,20, a self-binding A protein toxin produced by because of the potential negative economic impact pilus that tethers bacterial cells together21, possibly V. -

Vibrio Cholerae O1, O139)

Cholera! (Toxigenic Vibrio cholerae O1, O139) Note: Only toxigenic strains of Vibrio cholerae serogroups O1 and O139 cause epidemics and are reportable as cholera. This guidance is intended for management of patients with toxigenic strains of V. cholerae serogroups O1 and O139 and early management (i.e., before laboratory confirmation is available) of patients with cholera-like illness returning from regions where cholera activity has been reported (e.g., travelers returning from Haiti or the Dominican Republic). For management of non-toxigenic strains of V. cholerae O1 and O139, toxigenic strains of other V. cholerae serogroups (e.g. O75 and O141), and other Vibrio species, refer to the guidance for vibriosis. PROTOCOL CHECKLIST Enter available information into Merlin within 24 hours of notification Review background on disease, case definition, laboratory testing (section 2, 3, and 4) Contact provider (section 5) Confirm diagnosis Obtain available demographic and clinical information Determine what information was provided to the patient Ensure collection and submission of appropriate specimens (section 4) Interview patient(s) (section 5) Review disease facts (section 2) Description of illness Modes of transmission Ask about exposure to relevant risk factors (section 5) Travel to an area affected by cholera Exposure to untreated water sources Exposure to raw shellfish or undercooked seafood Consumption of food imported from an area affected by cholera Pre-existing conditions Identify any similar cases of illness among contacts Determine -

The Columbian Exchange: a History of Disease, Food, and Ideas

Journal of Economic Perspectives—Volume 24, Number 2—Spring 2010—Pages 163–188 The Columbian Exchange: A History of Disease, Food, and Ideas Nathan Nunn and Nancy Qian hhee CColumbianolumbian ExchangeExchange refersrefers toto thethe exchangeexchange ofof diseases,diseases, ideas,ideas, foodfood ccrops,rops, aandnd populationspopulations betweenbetween thethe NewNew WorldWorld andand thethe OldOld WWorldorld T ffollowingollowing thethe voyagevoyage ttoo tthehe AAmericasmericas bbyy ChristoChristo ppherher CColumbusolumbus inin 1492.1492. TThehe OldOld WWorld—byorld—by wwhichhich wwee mmeanean nnotot jjustust EEurope,urope, bbutut tthehe eentirentire EEasternastern HHemisphere—gainedemisphere—gained fromfrom tthehe CColumbianolumbian EExchangexchange iinn a nnumberumber ooff wways.ays. DDiscov-iscov- eeriesries ooff nnewew ssuppliesupplies ofof metalsmetals areare perhapsperhaps thethe bestbest kknown.nown. BButut thethe OldOld WWorldorld aalsolso ggainedained newnew staplestaple ccrops,rops, ssuchuch asas potatoes,potatoes, sweetsweet potatoes,potatoes, maize,maize, andand cassava.cassava. LessLess ccalorie-intensivealorie-intensive ffoods,oods, suchsuch asas tomatoes,tomatoes, chilichili peppers,peppers, cacao,cacao, peanuts,peanuts, andand pineap-pineap- pplesles wwereere aalsolso iintroduced,ntroduced, andand areare nownow culinaryculinary centerpiecescenterpieces inin manymany OldOld WorldWorld ccountries,ountries, namelynamely IItaly,taly, GGreece,reece, andand otherother MediterraneanMediterranean countriescountries (tomatoes),(tomatoes), -

Enteric Infections Due to Campylobacter, Yersinia, Salmonella, and Shigella*

Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 58 (4): 519-537 (1980) Enteric infections due to Campylobacter, Yersinia, Salmonella, and Shigella* WHO SCIENTIFIC WORKING GROUP1 This report reviews the available information on the clinical features, pathogenesis, bacteriology, and epidemiology ofCampylobacter jejuni and Yersinia enterocolitica, both of which have recently been recognized as important causes of enteric infection. In the fields of salmonellosis and shigellosis, important new epidemiological and relatedfindings that have implications for the control of these infections are described. Priority research activities in each ofthese areas are outlined. Of the organisms discussed in this article, Campylobacter jejuni and Yersinia entero- colitica have only recently been recognized as important causes of enteric infection, and accordingly the available knowledge on these pathogens is reviewed in full. In the better- known fields of salmonellosis (including typhoid fever) and shigellosis, the review is limited to new and important information that has implications for their control.! REVIEW OF RECENT KNOWLEDGE Campylobacterjejuni In the last few years, C.jejuni (previously called 'related vibrios') has emerged as an important cause of acute diarrhoeal disease. Although this organism was suspected of being a cause ofacute enteritis in man as early as 1954, it was not until 1972, in Belgium, that it was first shown to be a relatively common cause of diarrhoea. Since then, workers in Australia, Canada, Netherlands, Sweden, United Kingdom, and the United States of America have reported its isolation from 5-14% of diarrhoea cases and less than 1 % of asymptomatic persons. Most of the information given below is based on conclusions drawn from these studies in developed countries. -

Bacterial Foodborne and Diarrheal Disease National Case Surveillance

Bacterial Foodborne and Diarrheal Disease National Case Surveillance Annual Report, 2003 Enteric Diseases Epidemiology Branch Division of Foodborne, Bacterial and Mycotic Diseases National Center for Zoonotic, Vectorborne and Enteric Diseases Centers for Disease Control and Prevention The Bacterial Foodborne and Diarrheal Disease National Case Surveillance is published by the Enteric Diseases Epidemiology Branch, Division of Foodborne, Bacterial and Mycotic Diseases, National Center for Zoonotic, Vectorborne and Enteric Diseases, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA 30333 SUGGESTED CITATION Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Bacterial Foodborne and Diarrheal Disease National Case Surveillance. Annual Report, 2003. Atlanta Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2005: pg. Nos - 2 - Contents Executive Summary……………………………………………………………………………… - 4- Expanded Surveillance Summaries of Selected Pathogens and Diseases, 2003………………… -10- Botulism…………………………………………………………………………………. -10- Non-O157 Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli………………………………………-18- Salmonella………………………………………………………………………………...-22- Shigella……………………………………………………………………………………-28- Vibrio……………………………………………………………………………………...-33- Surveillance Data Sources and Background……………………………………………………... -40- National Notifiable Diseases Surveillance System and the National Electronic Telecommunications System for Surveillance…………………………………………… -40- Public Health Laboratory Information System…………………………………………... -41- Limitations common to NETSS and PHLIS…………………………………………….. -

Gonorrhea Also Called the "Clap" Or "Drip," Gonorrhea Is a Contagious Disease Transmitted Most Often Through Sexual Contact with an Infected Person

Gonorrhea Also called the "clap" or "drip," gonorrhea is a contagious disease transmitted most often through sexual contact with an infected person. Gonorrhea may also be spread by contact with infected bodily fluids, so that a mother could pass on the infection to her newborn during childbirth. Both men and women can get gonorrhea. The infection is easily spread and occurs most often in people who have many sex partners. What Causes Gonorrhea? Gonorrhea is caused by Neisseria gonorrhoeae, a bacterium that can grow and multiply easily in mucus membranes of the body. Gonorrhea bacteria can grow in the warm, moist areas of the reproductive tract, including the cervix (opening to the womb), uterus (womb), and fallopian tubes (egg canals) in women, and in the urethra (the tube that carries urine from the bladder to outside the body) in women and men. The bacteria can also grow in the mouth, throat, and anus. Gonorrhea symptoms in women ● Greenish yellow or whitish discharge from the vagina ● Lower abdominal or pelvic pain ● Burning when urinating ● Conjunctivitis (red, itchy eyes) ● Bleeding between periods ● Spotting after intercourse ● Swelling of the vulva (vulvitis) Gonorrhea symptoms in men ● Greenish yellow or whitish discharge from the penis ● Burning when urinating ● Burning in the throat (due to oral sex) ● Painful or swollen testicles ● Swollen glands in the throat (due to oral sex) In men, symptoms usually appear two to 14 days after infection. How Is Gonorrhea Treated? To cure a gonorrhea infection, your doctor will give you either an oral or injectable antibiotic. Your partner should also be treated at the same time to prevent reinfection and further spread of the disease. -

Influence of Environmental Conditions on Fatty Acid-Induced Changes in Vibrio Cholerae Persistence and Pathogenicity

University of Tennessee at Chattanooga UTC Scholar Student Research, Creative Works, and Honors Theses Publications 5-2019 Influence of environmental conditions on fatty acid-induced changes in Vibrio cholerae persistence and pathogenicity Abigail Doyle University of Tennessee at Chattanooga, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.utc.edu/honors-theses Part of the Environmental Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Doyle, Abigail, "Influence of environmental conditions on fatty acid-induced changes in Vibrio cholerae persistence and pathogenicity" (2019). Honors Theses. This Theses is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Research, Creative Works, and Publications at UTC Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of UTC Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Influence of environmental conditions on fatty acid-induced changes in Vibrio cholerae persistence and pathogenicity Abigail Lea Doyle Departmental Honors Thesis The University of Tennessee at Chattanooga Department of Civil and Chemical Engineering Examination Date: 08 April 2019 Bradley J. Harris, Ph.D. David Giles, Ph.D. Assistant Professor of Civil and Chemical Assistant Professor of Biology, Geology and Engineering Environmental Science Thesis Director Department Examiner ABSTRACT Vibrio cholerae, a Gram-negative bacterium, is responsible for the acute intestinal infection known as cholera. This illness is due in part to V. cholerae’s ability to sense and adapt to changing environments as it is ingested into the human body from brackish environments. It was shown in recent studies that this bacteria has the ability to uptake exogenous fatty acids, resulting in changes to V. -

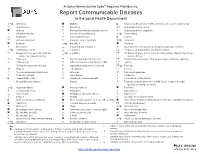

Report Communicable Diseases to the Local Health Department

Arizona Administrative Code Requires Providers to: Report Communicable Diseases to the Local Health Department *O Amebiasis Glanders O Respiratory disease in a health care institution or correctional facility Anaplasmosis Gonorrhea * Rubella (German measles) Anthrax Haemophilus influenzae, invasive disease Rubella syndrome, congenital Arboviral infection Hansen’s disease (Leprosy) *O Salmonellosis Babesiosis Hantavirus infection O Scabies Basidiobolomycosis Hemolytic uremic syndrome *O Shigellosis Botulism *O Hepatitis A Smallpox Brucellosis Hepatitis B and Hepatitis D Spotted fever rickettsiosis (e.g., Rocky Mountain spotted fever) *O Campylobacteriosis Hepatitis C Streptococcal group A infection, invasive disease Chagas infection and related disease *O Hepatitis E Streptococcal group B infection in an infant younger than 90 days of age, (American trypanosomiasis) invasive disease Chancroid HIV infection and related disease Streptococcus pneumoniae infection (pneumococcal invasive disease) Chikungunya Influenza-associated mortality in a child 1 Syphilis Chlamydia trachomatis infection Legionellosis (Legionnaires’ disease) *O Taeniasis * Cholera Leptospirosis Tetanus Coccidioidomycosis (Valley Fever) Listeriosis Toxic shock syndrome Colorado tick fever Lyme disease Trichinosis O Conjunctivitis, acute Lymphocytic choriomeningitis Tuberculosis, active disease Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease Malaria Tuberculosis latent infection in a child 5 years of age or younger (positive screening test result) *O Cryptosporidiosis -

Campylobacter Jejuni Survival Strategies

Campylobacter jejuni Survival Strategies and Counter-Attack: An investigation of Campylobacter phosphate mediated biofilms and the design of a high-throughput small- molecule screen for TAT inhibition DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Mary R Drozd Graduate Program in Veterinary Preventive Medicine The Ohio State University 2012 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Gireesh Rajashekara, Advisor, Dr. Mo Saif, Dr. Armando Hoet, and Dr. Daral Jackwood Copyrighted by Mary Rachel Drozd 2012 Abstract In these investigations we studied 1) the ability of Campylobacter to modulate its behavior in response to phosphate actuated signals, 2) the modulation of biofilm in response to phosphate related stressors, and 3) we designed and carried out a high- throughput small-molecule screen that targets protein transport via the Twin Arginine Translocation (TAT) system. We identified that the phoX , ppk1 and ppk2 genes were key components of the phosphate response that manifested increased biofilm phenotypes, and were modulated in the presence of inorganic phosphate. We used several molecular and microbiological techniques to investigate the effect of polyP, phosphate uptake inactivation, and inorganic phosphate availability on Campylobacter’s response to phosphate stress. Additionally, we counted and measured attached biofilms, as well as measured pellicle size, biofilm shedding over the course of three days, and changes in the expression of genes known to be involved in biofilm formation phenotypes. By resolving biofilm components such as pellicles, attached cells, and shed cells we found that not only did ppk1, phoX, and ppk2 deletion affect the ability of Campylobacter to form biofilms, but biofilm components were not congruently and equally affected in each mutant. -

Effects of Vibrio Cholerae Protease and Pigment Production on Environmental Survival and Host Interaction

Effects of Vibrio cholerae protease and pigment production on environmental survival and host interaction Karolis Vaitkevičius Department of Molecular Biology Umeå University Umeå 2007 1 Department of Molecular Biology Umeå University SE-90187 Umeå Sweden Copyright © 2007 by Karolis Vaitkevičius ISSN 0346-6612 ISBN 978-91-7264-464-9 Printed by Print & Media, Umeå University, Umeå, 2007 2 Table of content Abstract ......................................................................................................................................................... 5 Main articles of this thesis ............................................................................................................................ 6 Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 7 1. Cholera background .............................................................................................................................. 7 1.1. Serological classification of V. cholerae ......................................................................................... 8 2. Virulence factors of Vibrio cholerae and their biological function...................................................... 10 2.1. Cholera toxin ................................................................................................................................ 10 2.2 Toxin co-regulated pili (TCP) ........................................................................................................ -

Cholera Mortality During Urban Epidemic, Dar Es Salaam, Tanzania, August 16, 2015–January 16, 20161 Lindsey S

Cholera Mortality during Urban Epidemic, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, August 16, 2015–January 16, 20161 Lindsey S. McCrickard,2 Amani Elibariki Massay,2 Rupa Narra, Janneth Mghamba, Ahmed Abade Mohamed, Rogath Saika Kishimba, Loveness John Urio, Neema Rusibayamila, Grace Magembe, Muhammud Bakari, James J. Gibson, Rachel Barwick Eidex, Robert E. Quick In 2015, a cholera epidemic occurred in Tanzania; most Tanzania were experiencing cholera outbreaks (5). Chol- cases and deaths occurred in Dar es Salaam early in the era outbreaks can spread rapidly, crossing national borders, outbreak. We evaluated cholera mortality through passive and are a major global health security problem. surveillance, burial permits, and interviews conducted with Early in the Tanzania outbreak, most cases and deaths decedents’ caretakers. Active case finding identified 101 sus- were reported in Dar es Salaam, where 3,371 cases and pected cholera deaths. Routine surveillance had captured 36 deaths (case-fatality rate 1.1%) had been recorded by only 48 (48%) of all cholera deaths, and burial permit assess- ments captured the remainder. We interviewed caregivers of October 31, 2015. Deaths were exclusively reported from 56 decedents to assess cholera management behaviors. Of cholera treatment centers (CTCs), but additional deaths in 51 decedents receiving home care, 5 (10%) used oral rehy- the community were rumored. When cholera deaths in the dration solution after becoming ill. Caregivers reported that community were suspected, an environmental health officer 51 (93%) of 55 decedents with known time of death sought was required to visit the decedent’s house, prepare a burial care before death; 16 (29%) of 55 delayed seeking care for permit, obtain a rectal swab for culture, and assist with the >6 h. -

Vibrio Cholerae That Produce Enterotoxin 1

CHOLERA FACT SHEET Agent: Vibrio cholerae that produce enterotoxin 1. Specimen: Feces; Food (outbreak only) (serogroup O1 or serogroup O139) 2. Outfit: Stool culture; None provided for food Brief description: An acute bacterial infection of 3. Lab Form: 3416 for stool culture; 3450 for variable severity ranging from asymptomatic infec- food culture tion to profuse watery diarrhea. If severe disease is 4. Lab Test Performed: Culture of Vibrio not treated, rapid dehydration, acidosis, circulatory 5. Lab: Bacteriology Laboratory, Georgia collapse, hypoglycemia (in children), renal failure, Public Health Laboratory (GPHL) in and death can occur. Cholera is very rare in the Decatur. United States, with an average of 0-5 cases per year; B. Vibrio cholerae typing most of these have been linked to eating seafood 1. Specimen: Pure culture from the Louisiana and Texas Gulf Coast. Cholera is 2. Outfit: Culture referral a major cause of epidemic diarrhea in the developing 3. Lab Form: 3410 world. 4. Lab Test Performed: Vibrio cholerae typing 5. Lab: Bacteriology Laboratory, GPHL in Reservoir: Humans are the primary reservoir. Decatur. Environmental reservoirs are likely copepods and other zooplankton in brackish rivers and coastal NOTE: In outbreak situations, collect and estuaries. refrigerate food specimens for laboratory analysis. The food sample should be sent to the Mode of Transmission: Ingestion of food or water bacteriology lab using Lab Form 3450, through contaminated with stool or vomitus of infected coordination with the Epidemiology Branch persons. Also transmitted through eating raw or (404-657-2588). undercooked seafood that either comes from polluted waters or is naturally contaminated. Case Classification • Confirmed: A clinically compatible case Incubation Period: Usually 2-3 days, but ranges that is laboratory confirmed from a few hours to five days.