A Short (Architectural) History of the 20Th Century

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Copyright 2013 Shawn Patrick Gilmore

Copyright 2013 Shawn Patrick Gilmore THE INVENTION OF THE GRAPHIC NOVEL: UNDERGROUND COMIX AND CORPORATE AESTHETICS BY SHAWN PATRICK GILMORE DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2013 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Professor Michael Rothberg, Chair Professor Cary Nelson Associate Professor James Hansen Associate Professor Stephanie Foote ii Abstract This dissertation explores what I term the invention of the graphic novel, or more specifically, the process by which stories told in comics (or graphic narratives) form became longer, more complex, concerned with deeper themes and symbolism, and formally more coherent, ultimately requiring a new publication format, which came to be known as the graphic novel. This format was invented in fits and starts throughout the twentieth century, and I argue throughout this dissertation that only by examining the nuances of the publishing history of twentieth-century comics can we fully understand the process by which the graphic novel emerged. In particular, I show that previous studies of the history of comics tend to focus on one of two broad genealogies: 1) corporate, commercially-oriented, typically superhero-focused comic books, produced by teams of artists; 2) individually-produced, counter-cultural, typically autobiographical underground comix and their subsequent progeny. In this dissertation, I bring these two genealogies together, demonstrating that we can only truly understand the evolution of comics toward the graphic novel format by considering the movement of artists between these two camps and the works that they produced along the way. -

The University of Chicago Looking at Cartoons

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO LOOKING AT CARTOONS: THE ART, LABOR, AND TECHNOLOGY OF AMERICAN CEL ANIMATION A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE DIVISION OF THE HUMANITIES IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF CINEMA AND MEDIA STUDIES BY HANNAH MAITLAND FRANK CHICAGO, ILLINOIS AUGUST 2016 FOR MY FAMILY IN MEMORY OF MY FATHER Apparently he had examined them patiently picture by picture and imagined that they would be screened in the same way, failing at that time to grasp the principle of the cinematograph. —Flann O’Brien CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES...............................................................................................................................v ABSTRACT.......................................................................................................................................vii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS....................................................................................................................viii INTRODUCTION LOOKING AT LABOR......................................................................................1 CHAPTER 1 ANIMATION AND MONTAGE; or, Photographic Records of Documents...................................................22 CHAPTER 2 A VIEW OF THE WORLD Toward a Photographic Theory of Cel Animation ...................................72 CHAPTER 3 PARS PRO TOTO Character Animation and the Work of the Anonymous Artist................121 CHAPTER 4 THE MULTIPLICATION OF TRACES Xerographic Reproduction and One Hundred and One Dalmatians.......174 -

November 2019 - No

MEANWHILE FORM FOLLOWS DYSFUNCTION 741.5 NEW EXPERIMENTAL COMICS BY -HUIZENGA —WARE— HANSELMANN- NOVEMBER 2019 - NO. 35 PLUS...HILDA GOES HOLLYWOOD! Davis Lewis Trondheim Hubert Chevillard’s Travis Dandro Aimee de Jongh Dandro Sergio Toppi. The Comics & Graphic Novel Bulletin of Far away from the 3D blockbuster on funny animal comics stands out Galvan follows that pattern, but to emphasize the universality of mentality of commercial comics, a from the madding crowd. As usu- cools it down with geometric their stories as each make their new breed of cartoonists are ex- al, this issue of KE also runs mate- figures and a low-key approach to way through life in the Big City. In panding the means and meaning of rial from the past; this time, it’s narrative. Colors and shapes from contrast, Nickerson’s buildings the Ninth Art. Like its forebears Gasoline Alley Sunday pages and a Suprematist painting overlay a and backgrounds are very de- RAW and Blab!, the anthology Kra- Shary Flenniken’s sweet but sala- alien yet familiar world of dehu- tailed and life-like. That same mer’s Ergot provides a showcase of cious Trots & Bonnie strips from manized relationships defined by struggle between coherence and today’s most outrageous cartoon- the heyday of National Lampoon. hope and paranoia. In contrast to chaos is the central aspect of ists presenting comics that verge But most of this issue features Press Enter to Continue, Sylvia Tommi Masturi’s The Anthology of on avant garde art. The 10th issue work that comes on like W.S. -

Women's Experimental Autobiography from Counterculture Comics to Transmedia Storytelling: Staging Encounters Across Time, Space, and Medium

Women's Experimental Autobiography from Counterculture Comics to Transmedia Storytelling: Staging Encounters Across Time, Space, and Medium Dissertation Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Ohio State University Alexandra Mary Jenkins, M.A. Graduate Program in English The Ohio State University 2014 Dissertation Committee: Jared Gardner, Advisor Sean O’Sullivan Robyn Warhol Copyright by Alexandra Mary Jenkins 2014 Abstract Feminist activism in the United States and Europe during the 1960s and 1970s harnessed radical social thought and used innovative expressive forms in order to disrupt the “grand perspective” espoused by men in every field (Adorno 206). Feminist student activists often put their own female bodies on display to disrupt the disembodied “objective” thinking that still seemed to dominate the academy. The philosopher Theodor Adorno responded to one such action, the “bared breasts incident,” carried out by his radical students in Germany in 1969, in an essay, “Marginalia to Theory and Praxis.” In that essay, he defends himself against the students’ claim that he proved his lack of relevance to contemporary students when he failed to respond to the spectacle of their liberated bodies. He acknowledged that the protest movements seemed to offer thoughtful people a way “out of their self-isolation,” but ultimately, to replace philosophy with bodily spectacle would mean to miss the “infinitely progressive aspect of the separation of theory and praxis” (259, 266). Lisa Yun Lee argues that this separation continues to animate contemporary feminist debates, and that it is worth returning to Adorno’s reasoning, if we wish to understand women’s particular modes of theoretical ii insight in conversation with “grand perspectives” on cultural theory in the twenty-first century. -

It's Garfield's World, We Just Live in It

Bard College Bard Digital Commons Senior Projects Fall 2019 Bard Undergraduate Senior Projects Fall 2019 It’s Garfield’s World, We Just Live in It: An Exploration of Garfield the Cat as Icon, Money Maker, and Beast Iris B. Engel Bard College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.bard.edu/senproj_f2019 Part of the American Art and Architecture Commons, Animal Studies Commons, Arts Management Commons, Business Intelligence Commons, Commercial Law Commons, Contemporary Art Commons, Economics Commons, Finance and Financial Management Commons, Folklore Commons, Historic Preservation and Conservation Commons, Modern Art and Architecture Commons, Operations and Supply Chain Management Commons, Social Influence and oliticalP Communication Commons, Social Media Commons, Strategic Management Policy Commons, and the Theory and Criticism Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Engel, Iris B., "It’s Garfield’s World, We Just Live in It: An Exploration of Garfield the Cat as Icon, Money Maker, and Beast" (2019). Senior Projects Fall 2019. 3. https://digitalcommons.bard.edu/senproj_f2019/3 This Open Access work is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been provided to you by Bard College's Stevenson Library with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this work in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights- holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. For more information, please contact [email protected]. -

Network Map of Knowledge And

Humphry Davy George Grosz Patrick Galvin August Wilhelm von Hofmann Mervyn Gotsman Peter Blake Willa Cather Norman Vincent Peale Hans Holbein the Elder David Bomberg Hans Lewy Mark Ryden Juan Gris Ian Stevenson Charles Coleman (English painter) Mauritz de Haas David Drake Donald E. Westlake John Morton Blum Yehuda Amichai Stephen Smale Bernd and Hilla Becher Vitsentzos Kornaros Maxfield Parrish L. Sprague de Camp Derek Jarman Baron Carl von Rokitansky John LaFarge Richard Francis Burton Jamie Hewlett George Sterling Sergei Winogradsky Federico Halbherr Jean-Léon Gérôme William M. Bass Roy Lichtenstein Jacob Isaakszoon van Ruisdael Tony Cliff Julia Margaret Cameron Arnold Sommerfeld Adrian Willaert Olga Arsenievna Oleinik LeMoine Fitzgerald Christian Krohg Wilfred Thesiger Jean-Joseph Benjamin-Constant Eva Hesse `Abd Allah ibn `Abbas Him Mark Lai Clark Ashton Smith Clint Eastwood Therkel Mathiassen Bettie Page Frank DuMond Peter Whittle Salvador Espriu Gaetano Fichera William Cubley Jean Tinguely Amado Nervo Sarat Chandra Chattopadhyay Ferdinand Hodler Françoise Sagan Dave Meltzer Anton Julius Carlson Bela Cikoš Sesija John Cleese Kan Nyunt Charlotte Lamb Benjamin Silliman Howard Hendricks Jim Russell (cartoonist) Kate Chopin Gary Becker Harvey Kurtzman Michel Tapié John C. Maxwell Stan Pitt Henry Lawson Gustave Boulanger Wayne Shorter Irshad Kamil Joseph Greenberg Dungeons & Dragons Serbian epic poetry Adrian Ludwig Richter Eliseu Visconti Albert Maignan Syed Nazeer Husain Hakushu Kitahara Lim Cheng Hoe David Brin Bernard Ogilvie Dodge Star Wars Karel Capek Hudson River School Alfred Hitchcock Vladimir Colin Robert Kroetsch Shah Abdul Latif Bhittai Stephen Sondheim Robert Ludlum Frank Frazetta Walter Tevis Sax Rohmer Rafael Sabatini Ralph Nader Manon Gropius Aristide Maillol Ed Roth Jonathan Dordick Abdur Razzaq (Professor) John W. -

Download Zap Comix #16 PDF

Download: Zap Comix #16 PDF Free [760.Book] Download Zap Comix #16 PDF By R. Crumb, Gilbert Shelton, Robert Williams, S. Clay Wilson, Spain Rodriguez, Victor Moscoso, Paul Mavrides, Rick Griffin Zap Comix #16 you can download free book and read Zap Comix #16 for free here. Do you want to search free download Zap Comix #16 or free read online? If yes you visit a website that really true. If you want to download this ebook, i provide downloads as a pdf, kindle, word, txt, ppt, rar and zip. Download pdf #Zap Comix #16 | #380097 in Books | Fantagraphics Books | 2016-02-22 | Original language: English | PDF # 1 | 10.00 x .40 x 7.10l, .0 | File type: PDF | 96 pages | Fantagraphics Books | |18 of 18 people found the following review helpful.| Ah, well... | By Sean Burns |So here we are, almost 50 years after ZAP 1 appeared, with a sorta lackluster "farewell" from the old radicals that blew so many minds back in the day. But it's been a tough 50 years for many, they have nothing to prove and can rest on their laurels, and if they can make a little for their golden years, that's fine by me. ZAP 16 resembles an old | From Publishers Weekly | An iconic anthology bows out in a long-unpublished final issue featuring all of its premier artists, showcasing the differing styles that made each creator famous. Crumb's self-reflective comics (often published alongside those of Aline Ko The final, previously-only-available-in-a limited/collector's-edition issue of the the most important comic book series of all time! This blowout issue not only includes work by all eight Zap artists (plus a collaboration with cartoonist Aline Kominsky), but also three double-page jams by the group. -

Check All That Apply)

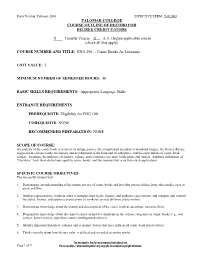

Form Version: February 2001 EFFECTIVE TERM: Fall 2003 PALOMAR COLLEGE COURSE OUTLINE OF RECORD FOR DEGREE CREDIT COURSE X Transfer Course X A.A. Degree applicable course (check all that apply) COURSE NUMBER AND TITLE: ENG 290 -- Comic Books As Literature UNIT VALUE: 3 MINIMUM NUMBER OF SEMESTER HOURS: 48 BASIC SKILLS REQUIREMENTS: Appropriate Language Skills ENTRANCE REQUIREMENTS PREREQUISITE: Eligibility for ENG 100 COREQUISITE: NONE RECOMMENDED PREPARATION: NONE SCOPE OF COURSE: An analysis of the comic book in terms of its unique poetics (the complicated interplay of word and image); the themes that are suggested in various works; the history and development of the form and its subgenres; and the expectations of comic book readers. Examines the influence of history, culture, and economics on comic book artists and writers. Explores definitions of “literature,” how these definitions apply to comic books, and the tensions that arise from such applications. SPECIFIC COURSE OBJECTIVES: The successful student will: 1. Demonstrate an understanding of the unique poetics of comic books and how that poetics differs from other media, such as prose and film. 2. Analyze representative works in order to interpret their styles, themes, and audience expectations, and compare and contrast the styles, themes, and audience expectations of works by several different artists/writers. 3. Demonstrate knowledge about the history and development of the comic book as an artistic, narrative form. 4. Demonstrate knowledge about the characteristics of and developments in the various subgenres of comic books (e.g., war comics, horror comics, superhero comics, underground comics). 5. Identify important historical, cultural, and economic factors that have influenced comic book artists/writers. -

LOCAS: the MAGGIE and HOPEY STORIES by Jaime Hernandez Study Guide Written by Art Baxter

NACAE National Association of Comics Art Educators STUDY GUIDE: LOCAS: THE MAGGIE AND HOPEY STORIES by Jaime Hernandez Study guide written by Art Baxter Introduction Comic books were in the midst of change by the early 1980s. The Marvel, DC and Archie lines were going through the same tired motions being produced by second and third generation artists and writers who grew up reading the same books they were now creating. Comic book specialty shops were growing in number and a new "non- returnable" distribution system had been created to supply them. This opened the door for publishers who had small print runs, with color covers and black and white interiors, to emerge with an alternative to corporate mainstream comics. These new comics were often a cross between the familiar genres of the mainstream and the personal artistic freedom of underground comics, but sometimes something altogether different would appear. In 1976, Harvey Pekar began self-publishing his annual autobiographical comics collection, American Splendor, with art by R. Crumb and others, from his home in Cleveland, Ohio. Other cartoonists self-published their mainstream- rejected comics, like Cerebus (Dave Sim, 1977) and Elfquest (Wendy & Richard Pini, 1978) to financial and critical success. With proto-graphic novel publisher, Eclipse, mainstream rebels produced explicit versions of their earlier work, such as Sabre (Don McGreggor & Paul Gulacy, 1978) and Stewart the Rat (Steve Gerber & Gene Colan, 1980). Underground comics evolved away from sex and drugs toward maturity in two anthologies, RAW (Art Spiegleman & Francoise Mouly, eds., 1980) and Weirdo (R. Crumb, ed., 1981). Under the Fantagraphics Books imprint, Gary Groth and Kim Thompson began to publish comics which aspired to an artistic quality that lived up to the high standard set forth in the pages of their critical magazine, The Comics Journal. -

THE COMIX BOOK LIFE of DENIS KITCHEN Spring 2014 • the New Voice of the Comics Medium • Number 5 Table of Contents

THE COMIX BOOK LIFE OF DENIS KITCHEN 0 2 1 82658 97073 4 in theUSA $ 8.95 ADULTS ONLY! A TwoMorrows Publication TwoMorrows Cover art byDenisKitchen No. 5,Spring2014 ™ Spring 2014 • The New Voice of the Comics Medium • Number 5 TABLE OF CONTENTS HIPPIE W©©DY Ye Ed’s Rant: Talking up Kitchen, Wild Bill, Cruse, and upcoming CBC changes ............ 2 CBC mascot by J.D. KING ©2014 J.D. King. COMICS CHATTER About Our Bob Fingerman: The cartoonist is slaving for his monthly Minimum Wage .................. 3 Cover Incoming: Neal Adams and CBC’s editor take a sound thrashing from readers ............. 8 Art by DENIS KITCHEN The Good Stuff: Jorge Khoury on artist Frank Espinosa’s latest triumph ..................... 12 Color by BR YANT PAUL Hembeck’s Dateline: Our Man Fred recalls his Kitchen Sink contributions ................ 14 JOHNSON Coming Soon in CBC: Howard Cruse, Vanguard Cartoonist Announcement that Ye Ed’s comprehensive talk with the 2014 MOCCA guest of honor and award-winning author of Stuck Rubber Baby will be coming this fall...... 15 REMEMBERING WILD BILL EVERETT The Last Splash: Blake Bell traces the final, glorious years of Bill Everett and the man’s exquisite final run on Sub-Mariner in a poignant, sober crescendo of life ..... 16 Fish Stories: Separating the facts from myth regarding William Blake Everett ........... 23 Cowan Considered: Part two of Michael Aushenker’s interview with Denys Cowan on the man’s years in cartoon animation and a triumphant return to comics ............ 24 Art ©2014 Denis Kitchen. Dr. Wertham’s Sloppy Seduction: Prof. Carol L. Tilley discusses her findings of DENIS KITCHEN included three shoddy research and falsified evidence inSeduction of the Innocent, the notorious in-jokes on our cover that his observant close friends might book that almost took down the entire comic book industry .................................... -

Free Catalog

Featured New Items DC COLLECTING THE MULTIVERSE On our Cover The Art of Sideshow By Andrew Farago. Recommended. MASTERPIECES OF FANTASY ART Delve into DC Comics figures and Our Highest Recom- sculptures with this deluxe book, mendation. By Dian which features insights from legendary Hanson. Art by Frazetta, artists and eye-popping photography. Boris, Whelan, Jones, Sideshow is world famous for bringing Hildebrandt, Giger, DC Comics characters to life through Whelan, Matthews et remarkably realistic figures and highly al. This monster-sized expressive sculptures. From Batman and Wonder Woman to The tome features original Joker and Harley Quinn...key artists tell the story behind each paintings, contextualized extraordinary piece, revealing the design decisions and expert by preparatory sketches, sculpting required to make the DC multiverse--from comics, film, sculptures, calen- television, video games, and beyond--into a reality. dars, magazines, and Insight Editions, 2020. paperback books for an DCCOLMSH. HC, 10x12, 296pg, FC $75.00 $65.00 immersive dive into this SIDESHOW FINE ART PRINTS Vol 1 dynamic, fanciful genre. Highly Recommened. By Matthew K. Insightful bios go beyond Manning. Afterword by Tom Gilliland. Wikipedia to give a more Working with top artists such as Alex Ross, accurate and eye-opening Olivia, Paolo Rivera, Adi Granov, Stanley look into the life of each “Artgerm” Lau, and four others, Sideshow artist. Complete with fold- has developed a series of beautifully crafted outs and tipped-in chapter prints based on films, comics, TV, and ani- openers, this collection will mation. These officially licensed illustrations reign as the most exquisite are inspired by countless fan-favorite prop- and informative guide to erties, including everything from Marvel and this popular subject for DC heroes and heroines and Star Wars, to iconic classics like years to come. -

Rip Off Press Mail Order • PO Box 4686 • Auburn, CA 95604 • 530 885

Rip Off Press Mail Order • PO Box 4686 • Auburn, CA 95604 • 530 885-8183 Toll Free inside the U.S.: 888-978-3049 • e-mail: [email protected] •www.ripoffpress.com MINI ORDER FORM AND IN-STOCK PRODUCT LIST - MARK ITEMS WANTED AND MAIL WITH PAYMENT or charge card information SHIP TO: PAYMENT WORKSHEET Name___________________________________________________ MERCHANDISE TOTAL__________ Address_________________________________________________ (This is the amount on which your Shipping Rate is based - see the chart below) City_____________________________________________________ CALIFORNIA SALES TAX__________ State_________ ZIP_____________________________ (For shipment inside CALIF. ONLY: 7.5%--No tax outside Calif.) Day Phone_____________________e-mail___________________ SHIPPING & HANDLING CHARGE__________ Based on the Merchandise Total for each type of items ordered -- See the CHARTS below. I AM OVER 18 (Sign for ordering * titles) ___________________________ SUBTRACT ANY CREDITS__________ For Charge Card orders please fill in the blanks: YOUR COPY OF CREDIT MEMO/GIFT CERT./DISCOUNT CERT. MUST BE ENCLOSED ACCT. No._____________________________________________ Sec. Code_______ ADD ANY BALANCE DUE FROM BEFORE__________ Thank you!! Signature________________________________________________Exp.__________ GRAND TOTAL__________ Cardholder name (print)_________________________________________________ Enclose check or money order made out in U.S. dollars Acct. Addr. (if different from “Ship To”)_________________________________________ Or fill