Constitutionalism and the Dilemma of Judicial Autonomy in Pakistan: a Critical Analysis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

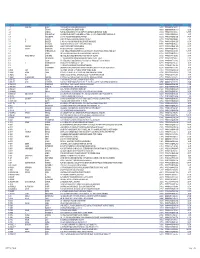

Complete List of Books in Library Acc No Author Title of Book Subject Publisher Year R.No

Complete List of Books in Library Acc No Author Title of book Subject Publisher Year R.No. 1 Satkari Mookerjee The Jaina Philosophy of PHIL Bharat Jaina Parisat 8/A1 Non-Absolutism 3 Swami Nikilananda Ramakrishna PER/BIO Rider & Co. 17/B2 4 Selwyn Gurney Champion Readings From World ECO `Watts & Co., London 14/B2 & Dorothy Short Religion 6 Bhupendra Datta Swami Vivekananda PER/BIO Nababharat Pub., 17/A3 Calcutta 7 H.D. Lewis The Principal Upanisads PHIL George Allen & Unwin 8/A1 14 Jawaherlal Nehru Buddhist Texts PHIL Bruno Cassirer 8/A1 15 Bhagwat Saran Women In Rgveda PHIL Nada Kishore & Bros., 8/A1 Benares. 15 Bhagwat Saran Upadhya Women in Rgveda LIT 9/B1 16 A.P. Karmarkar The Religions of India PHIL Mira Publishing Lonavla 8/A1 House 17 Shri Krishna Menon Atma-Darshan PHIL Sri Vidya Samiti 8/A1 Atmananda 20 Henri de Lubac S.J. Aspects of Budhism PHIL sheed & ward 8/A1 21 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad Bhagabatam PHIL Dhirendra Nath Bose 8/A2 22 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam VolI 23 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam Vo.l III 24 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad Bhagabatam PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 25 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam Vol.V 26 Mahadev Desai The Gospel of Selfless G/REL Navijvan Press 14/B2 Action 28 Shankar Shankar's Children Art FIC/NOV Yamuna Shankar 2/A2 Number Volume 28 29 Nil The Adyar Library Bulletin LIT The Adyar Library and 9/B2 Research Centre 30 Fraser & Edwards Life And Teaching of PER/BIO Christian Literature 17/A3 Tukaram Society for India 40 Monier Williams Hinduism PHIL Susil Gupta (India) Ltd. -

Muslim Nationalism, State Formation and Legal Representations of the Ahmadiyya Community in Pakistan

Politics of Exclusion: Muslim Nationalism, State Formation and Legal Representations of the Ahmadiyya Community in Pakistan by Sadia Saeed A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Sociology) in The University of Michigan 2010 Doctoral Committee: Professor George P. Steinmetz, Chair Professor Howard A. Kimeldorf Associate Professor Fatma Muge Gocek Associate Professor Genevieve Zubrzycki Professor Mamadou Diouf, Columbia University © Sadia Saeed 2010 2 Dedication This dissertation is dedicated to my parents with my deepest love, respect and gratitude for the innumerable ways they have supported my work and choices. ii Acknowledgements I would like to begin by acknowledging the immense support my parents have given me every step of the way during my (near) decade in graduate school. I have dedicated this dissertation to them. My ammi and baba have always believed in my capabilities to accomplish not only this dissertation but much more in life and their words of love and encouragement have continuously given me the strength and the will to give my research my very best. My father‘s great enthusiasm for this project, his intellectual input and his practical help and advice during the fieldwork of this project have been formative to this project. I would like to thank my dissertation advisor George Steinmetz for the many engaged conversations about theory and methods, for always pushing me to take my work to the next level and above all for teaching me to recognize and avoid sloppiness, caricatures and short-cuts. It is to him that I owe my greatest intellectual debt. -

GTL Limited Unpaid / Unclaimed Dividend for the Year 2009-10 Information As on : 21-Sep-2016 Ltr. No. Name Country State Distric

GTL Limited Unpaid / Unclaimed Dividend for the year 2009-10 Information ason : 21-Sep-2016 Amount Due (in Proposed Date of transfer to Ltr. No. Name Country State District Pincode InvestmentType Rs.) IEPF (DD-MON-YYYY) IEPF-1 A ABIDA BEGUM INDIA KARNATAKA BANGALORE 560016 Amount for unclaimed and unpaid dividend 15.00 25-AUG-2017 IEPF-2 A DHILIP CHAND INDIA TAMIL NADU TIRUVANNAMALAI 606601 Amount for unclaimed and unpaid dividend 150.00 25-AUG-2017 IEPF-3 A ESWARAMURTHY INDIA TAMIL NADU KRISHNAGIRI 635126 Amount for unclaimed and unpaid dividend 6.00 25-AUG-2017 IEPF-4 A H BADAT INDIA ANDAMAN AND NICOBAR ISLANDS SOUTH ANDAMAN 744101 Amount for unclaimed and unpaid dividend 150.00 25-AUG-2017 IEPF-5 A JAYALAKSHMI INDIA TAMIL NADU CHENNAI 600033 Amount for unclaimed and unpaid dividend 42.00 25-AUG-2017 IEPF-6 A K MANDAL INDIA UTTAR PRADESH LUCKNOW 226016 Amount for unclaimed and unpaid dividend 642.00 25-AUG-2017 IEPF-7 A M JAGADEESH INDIA KARNATAKA BANGALORE 560094 Amount for unclaimed and unpaid dividend 171.00 25-AUG-2017 IEPF-8 A PRADEEP KUMAR INDIA ORISSA GANJAM 760004 Amount for unclaimed and unpaid dividend 30.00 25-AUG-2017 IEPF-9 A RAJMOHAN INDIA KARNATAKA DAKSHINA KANNADA 575001 Amount for unclaimed and unpaid dividend 15.00 25-AUG-2017 IEPF-10 A SAI KRISHNA INDIA ANDHRA PRADESH HYDERABAD 500029 Amount for unclaimed and unpaid dividend 999.00 25-AUG-2017 IEPF-11 A SAJIDAS INDIA KERALA THIRUVANANTHAPURAM 695571 Amount for unclaimed and unpaid dividend 342.00 25-AUG-2017 IEPF-12 A SATYANARAYANA REDDY INDIA ANDHRA PRADESH HYDERABAD -

Political Instability in Pakistan: Can a Democratic Federal Political System Resolve the Problem of Premature Dissolutions of Government in Pakistan?

POLITICAL INSTABILITY IN PAKISTAN: CAN A DEMOCRATIC FEDERAL POLITICAL SYSTEM RESOLVE THE PROBLEM OF PREMATURE DISSOLUTIONS OF GOVERNMENT IN PAKISTAN? Aamir Nawaz A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirement of Nottingham Trent University for the degree of Doctorate in Legal Practice December 2018 Blank Page Copyright © Statement This work is the intellectual property of the author. You may copy up to 5% of this work for private study, or personal, non-commercial research. Any re-use of the information contained within this document should be fully referenced, quoting the author, title, university, degree level and pagination. Queries or requests for any other use, or if a more substantial copy is required, should be directed to the author. Blank Page Dedication This humble contribution I dedicate to the people of Pakistan – those who have sacrificed and endured a lot in their lives for a long time. The people of Pakistan deserve a stable country with a secure future for themselves and their children. And To my father for his firm faith in me that has always motivated me in my life Blank Page Table of Contents Abstract ........................................................................................................ 1 Table of Statute and Legal Instruments ......................................................... 2 Table of Cases ............................................................................................... 2 1. Introduction ........................................................................................ -

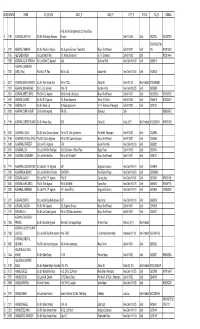

SR NO First Name Middle Name Last Name Address Pincode Folio

SR NO First Name Middle Name Last Name Address Pincode Folio Amount 1 A SPRAKASH REDDY 25 A D REGIMENT C/O 56 APO AMBALA CANTT 133001 0000IN30047642435822 22.50 2 A THYAGRAJ 19 JAYA CHEDANAGAR CHEMBUR MUMBAI 400089 0000000000VQA0017773 135.00 3 A SRINIVAS FLAT NO 305 BUILDING NO 30 VSNL STAFF QTRS OSHIWARA JOGESHWARI MUMBAI 400102 0000IN30047641828243 1,800.00 4 A PURUSHOTHAM C/O SREE KRISHNA MURTY & SON MEDICAL STORES 9 10 32 D S TEMPLE STREET WARANGAL AP 506002 0000IN30102220028476 90.00 5 A VASUNDHARA 29-19-70 II FLR DORNAKAL ROAD VIJAYAWADA 520002 0000000000VQA0034395 405.00 6 A H SRINIVAS H NO 2-220, NEAR S B H, MADHURANAGAR, KAKINADA, 533004 0000IN30226910944446 112.50 7 A R BASHEER D. NO. 10-24-1038 JUMMA MASJID ROAD, BUNDER MANGALORE 575001 0000000000VQA0032687 135.00 8 A NATARAJAN ANUGRAHA 9 SUBADRAL STREET TRIPLICANE CHENNAI 600005 0000000000VQA0042317 135.00 9 A GAYATHRI BHASKARAAN 48/B16 GIRIAPPA ROAD T NAGAR CHENNAI 600017 0000000000VQA0041978 135.00 10 A VATSALA BHASKARAN 48/B16 GIRIAPPA ROAD T NAGAR CHENNAI 600017 0000000000VQA0041977 135.00 11 A DHEENADAYALAN 14 AND 15 BALASUBRAMANI STREET GAJAVINAYAGA CITY, VENKATAPURAM CHENNAI, TAMILNADU 600053 0000IN30154914678295 1,350.00 12 A AYINAN NO 34 JEEVANANDAM STREET VINAYAKAPURAM AMBATTUR CHENNAI 600053 0000000000VQA0042517 135.00 13 A RAJASHANMUGA SUNDARAM NO 5 THELUNGU STREET ORATHANADU POST AND TK THANJAVUR 614625 0000IN30177414782892 180.00 14 A PALANICHAMY 1 / 28B ANNA COLONY KONAR CHATRAM MALLIYAMPATTU POST TRICHY 620102 0000IN30108022454737 112.50 15 A Vasanthi W/o G -

Stamps of India - Commemorative by Prem Pues Kumar [email protected] 9029057890

E-Book - 26. Checklist - Stamps of India - Commemorative By Prem Pues Kumar [email protected] 9029057890 For HOBBY PROMOTION E-BOOKS SERIES - 26. FREE DISTRIBUTION ONLY DO NOT ALTER ANY DATA ISBN - 1st Edition Year - 1st May 2020 [email protected] Prem Pues Kumar 9029057890 Page 1 of 76 Nos. YEAR PRICE NAME Mint FDC B. 1 2 3 1947 1 21-Nov-47 31/2a National Flag 2 15-Dec-47 11/2a Ashoka Lion Capital 3 15-Dec-47 12a Aircraft 1948 4 29-May-48 12a Air India International 5 15-Aug-48 11/2a Mahatma Gandhi 6 15-Aug-48 31/2a Mahatma Gandhi 7 15-Aug-48 12a Mahatma Gandhi 8 15-Aug-48 10r Mahatma Gandhi 1949 9 10-Oct-49 9 Pies 75th Anni. of Universal Postal Union 10 10-Oct-49 2a -do- 11 10-Oct-49 31/2a -do- 12 10-Oct-49 12a -do- 1950 13 26-Jan-50 2a Inauguration of Republic of India- Rejoicing crowds 14 26-Jan-50 31/2a Quill, Ink-well & Verse 15 26-Jan-50 4a Corn and plough 16 26-Jan-50 12a Charkha and cloth 1951 17 13-Jan-51 2a Geological Survey of India 18 04-Mar-51 2a First Asian Games 19 04-Mar-51 12a -do- 1952 20 01-Oct-52 9 Pies Saints and poets - Kabir 21 01-Oct-52 1a Saints and poets - Tulsidas 22 01-Oct-52 2a Saints and poets - MiraBai 23 01-Oct-52 4a Saints and poets - Surdas 24 01-Oct-52 41/2a Saints and poets - Mirza Galib 25 01-Oct-52 12a Saints and poets - Rabindranath Tagore 1953 26 16-Apr-53 2a Railway Centenary 27 02-Oct-53 2a Conquest of Everest 28 02-Oct-53 14a -do- 29 01-Nov-53 2a Telegraph Centenary 30 01-Nov-53 12a -do- 1954 31 01-Oct-54 1a Stamp Centenary - Runner, Camel and Bullock Cart 32 01-Oct-54 2a Stamp Centenary -

List of Stamps from 1852 Onwards

LIST OF STAMPS FROM 1852 ONWARDS POSTAGE STAMPS – PRE-INDEPENDENCE Year Denomination Particulars 1 1852 /2a SCINDE DAWK 1 1854 /2a EAST INDIA CO, ISSUES 1a -do- 4a -do- 1854 4a QUEEN VICTORIA 1 /2a -do- 1a -do- 2a -do- 1855 4a -do- 8a -do- 1 1856-64 /2a -do- 1a -do- 2a -do- 4a -do- 8a -do- UNDER THE CROWN - QUEEN 1860 8p VICTORIA 1 1865 /2a Elephant’s Head Watermark 8p -do- 1a -do- 2a -do- 4a -do- 8a -do- 1866 6a -do- 1866-67 4a Octagonal design 6a8p -do- 1868 8a Die II 1 1873 /2a -do- 1874 9p -do- 1r -do- 1876 6a 12a 1 LIST OF STAMPS FROM 1852 ONWARDS 1 1882-88 /2a Empire of India – Queen Victoria 9p -do- 1a -do- 1a6p -do- 2a -do- 3a -do- 4a -do- 4a6p -do- 8a -do- 12a -do- 1R -do- 1 1891 2 /2a Surcharged 1 1892-97 2 /2a 1r 1895 2r 3r 5r 1 1898 /4a 1899 3p 1900-02 3p 1 /2a 1a 2a 1 2 /2a 1902-11 3p KING EDWARD VII 1 /2a -do- 1a -do- 2a -do- 1 2 /2a -do- 3a -do- 4a -do- 6a -do- 8a -do- 12a -do- 1r -do- 2r -do- 2 LIST OF STAMPS FROM 1852 ONWARDS 3r -do- 5r -do- 10r -do- 15r -do- 25r -do- 1 1905 /4a Surcharged 1 1906 /2a Postage and Revenue 1a -do- 1911 3p KING GEORGE V 1 /2a -do- 1a -do- 1 1 /2a -do- 2a -do- 1 2 /2a -do- 3a -do- 4a -do- 6a -do- 8a -do- 12a -do- 1r -do- 2r -do- 5r -do- 10r -do- 15r -do- 25r -do- 1921 9p Surcharged 1 1922 /4a -do- 1922-26 1a Colours changed 1 1 /2a -do- 1 2 /2a -do- 3a -do- 1926-31 3p Printed at ISP Nasik 1 /2a -do- 1a -do- 1 1 /2a -do- 2a -do- 3 LIST OF STAMPS FROM 1852 ONWARDS 1 2 /2a -do- 3a -do- 4a -do- 8a -do- 12a -do- 1r -do- 2r -do- 5r -do- 10r -do- 15r -do- 25r -do- 1929 2a Air Mail Series 3a -do- 4a -

Main Voter List 08.01.2018.Pdf

Sl.NO ADM.NO NAME SO_DO_WO ADD1_R ADD2_R CITY_R STATE TEL_R MOBILE 61-B, Abul Fazal Apartments 22, Vasundhara 1 1150 ACHARJEE,AMITAVA S/o Shri Sudhamay Acharjee Enclave Delhi-110 096 Delhi 22620723 9312282751 22752142,22794 2 0181 ADHYARU,YASHANK S/o Shri Pravin K. Adhyaru 295, Supreme Enclave, Tower No.3, Mayur Vihar Phase-I Delhi-110 091 Delhi 745 9810813583 3 0155 AELTEMESH REIN S/o Late Shri M. Rein 107, Natraj Apartments 67, I.P. Extension Delhi-110 092 Delhi 9810214464 4 1298 AGARWAL,ALOK KRISHNA S/o Late Shri K.C. Agarwal A-56, Gulmohar Park New Delhi-110 049 Delhi 26851313 AGARWAL,DARSHANA 5 1337 (MRS.) (Faizi) W/o Shri O.P. Faizi Flat No. 258, Kailash Hills New Delhi-110 065 Delhi 51621300 6 0317 AGARWAL,MAM CHANDRA S/o Shri Ram Sharan Das Flat No.1133, Sector-29, Noida-201 301 Uttar Pradesh 0120-2453952 7 1427 AGARWAL,MOHAN BABU S/o Dr. C.B. Agarwal H.No. 78, Sukhdev Vihar New Delhi-110 025 Delhi 26919586 8 1021 AGARWAL,NEETA (MRS.) W/o Shri K.C. Agarwal B-608, Anand Lok Society Mayur Vihar Phase-I Delhi-110 091 Delhi 9312059240 9810139122 9 0687 AGARWAL,RAJEEV S/o Shri R.C. Agarwal 244, Bharat Apartment Sector-13, Rohini Delhi-110 085 Delhi 27554674 9810028877 11 1400 AGARWAL,S.K. S/o Shri Kishan Lal 78, Kirpal Apartments 44, I.P. Extension, Patparganj Delhi-110 092 Delhi 22721132 12 0933 AGARWAL,SUNIL KUMAR S/o Murlidhar Agarwal WB-106, Shakarpur, Delhi 9868036752 13 1199 AGARWAL,SURESH KUMAR S/o Shri Narain Dass B-28, Sector-53 Noida, (UP) Uttar Pradesh0120-2583477 9818791243 15 0242 AGGARWAL,ARUN S/o Shri Uma Shankar Agarwal Flat No.26, Trilok Apartments Plot No.85, Patparganj Delhi-110 092 Delhi 22433988 16 0194 AGGARWAL,MRIDUL (MRS.) W/o Shri Rajesh Aggarwal Flat No.214, Supreme Enclave Mayur Vihar Phase-I, Delhi-110 091 Delhi 22795565 17 0484 AGGARWAL,PRADEEP S/o Late R.P. -

MANALI PETROCHEMICALS LIMITED CIN : L24294TN1986PLC013087 Regd Off: 'SPIC HOUSE', 88, Mount Road, Guindy, Chennai- 600 032

MANALI PETROCHEMICALS LIMITED CIN : L24294TN1986PLC013087 Regd Off: 'SPIC HOUSE', 88, Mount Road, Guindy, Chennai- 600 032. Tele-Fax No.: 044-22351098 Email: [email protected], Website: www.manalipetro.com DETAILS OF SHARES TO BE TRANSFERRED TO INVESTOR EDUCATION & PROTECTION FUND ON WHICH NO DIVIDEND HAS BEEN CLAIMED FOR THE FY 2008-09 TO 2015-16 SL.NO FOLIO_DP_ID_CL_ID NAME OF THE SHAREHOLDER NO.OF.SHARES TOBE TRFD TO IEPF 1 A0000033 SITARAMAN G 450 2 A0000089 LAKSHMANAN CHELLADURAI 300 3 A0000093 MANI N V S 150 4 A0000101 KUNNATH NARAYANAN SUBRAMANIAN 300 5 A0000120 GOPAL THACHAT MURALIDHAR 300 6 A0000130 ROY FESTUS 150 7 A0000140 SATHYAMURTHY N 300 8 A0000142 MOHAN RAO V 150 9 A0000170 MURALIDHARAN M R 300 10 A0000171 CHANDRASEKAR V 150 11 A0000187 VISWANATH J 300 12 A0000191 JAGMOHAN SINGH BIST 300 13 A0000213 MURUGANANDAN RAMACHANDRAN 150 14 A0000219 SHANMUGAM E 600 15 A0000232 VENKATRAMAN N 150 16 A0000235 KHADER HUSSAINY S M 150 17 A0000325 PARAMJEET SINGH BINDRA 300 18 A0000332 SELVARAJU G 300 19 A0000334 RAJA VAIDYANATHAN R 300 20 A0000339 PONNUSWAMY SAMPANGIRAM 300 21 A0000356 GANESH MAHADHEVAN 150 22 A0000381 MEENAKSHI SUNDARAM K 150 23 A0000389 CHINNIAH A 150 24 A0000392 PERUMAL K 300 25 A0000423 CHANDRASEKARAN C 300 26 A0000450 RAMAMOORTHY NAIDU MADUPURI 150 27 A0000473 ZULFIKAR ALI SULTAN MOHAMMAD 300 28 A0000550 SRINIVASAN K 150 29 A0000556 KANAKAMUTHU A 300 30 A0000561 KODANDA PANI CHIVUKULA 300 31 A0000565 VARADHAN R 150 32 A0000566 KARTHIGEYAN S 150 33 A0000598 RAMASASTRULU TRIPIRNENI 150 34 A0000620 -

University of Warwick Institutional Repository

University of Warwick institutional repository: http://go.warwick.ac.uk/wrap A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of Warwick http://go.warwick.ac.uk/wrap/66360 This thesis is made available online and is protected by original copyright. Please scroll down to view the document itself. Please refer to the repository record for this item for information to help you to cite it. Our policy information is available from the repository home page. Contested Legalities, (De)Coloniality and the State: Understanding the Socio-Legal Tapestry of Pakistan by Raza Saeed A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Law University of Warwick, School of Law 1 April, 2014 Table of Contents Acknowledgements ........................................................................................................................... i Declaration ......................................................................................................................................... iii Abstract ................................................................................................................................................ iv Abbreviations ...................................................................................................................................... v Glossary .............................................................................................................................................. vii Statutes Cited ................................................................................................................................... -

CIJL Bulletin-23-1989-Eng

CIJL BULLETIN N° 23 SPECIAL ISSUE ICJ CONFERENCE ON THE INDEPENDENCE OF JUDGES AND LAWYERS CARACAS, VENEZUELA 16-18 JANUARY 1989 UNDER THE AUSPICES OF THE UNITED NATIONS CENTRE FOR THE INDEPENDENCE OF JUDGES AND LAWYERS April 1989 Editor: Reed Brody The Centre for the Independence of Judges and Lawyers was created by the Inter national Commission of Jurists in 1978 to counter serious inroads into the indepen dence of the judiciary and the legal profession by: - promoting world-wide the basic need for an independent judiciary and legal pro fession; - organising support for judges and lawyers who are being harassed or persecuted. The work of the Centre is supported by contributions from lawyers’ organisations and private foundations. There remains a substantial deficit to be met. We hope that bar associations and other lawyers’ organisations concerned with the fate of their col leagues around the world will provide the financial support essential to the survival of the Centre. Affiliation The affiliation of judges’, lawyers’ and jurists’ organisations is welcomed. Interested organisations are invited to write to the Director, CIJL, at the address indicated below. Individual Contributors Individuals may support the work of the Centre by becoming Contributors to the CIJL and making a contribution of not less than SFr. 100.- per year. Contributors will receive all publications of the Centre and the International Commmission of Jurists. Subscription to CIJL Bulletin Subscriptions to the twice yearly Bulletin are SFr. 12 - per year surface mail, or SFr. 18.- per year airmail. Payment may be made in Swiss Francs or in the equivalent amount in other currencies either by direct cheque valid for external payment or through a bank to Societe de Banque Suisse, Geneva, account No. -

Aba Umar Dada Abdul Aziz Kaya

Memon Personalities Aba Umar Dada Late Mr. Dada was a well-known community leader and social worker. He was a prominent member of Karachi Cotton Exchange who earned a name for himself. After the establishment of Pakistan, he settled in the interior of Sindh and took leading part in all social and welfare activities of Hyderabad and Sindh. Settling in Karachi, he continued with his social work and was very active amongst the leaders of the Pakistan Memon Federation. Ahmed H.A. Dada He was a very prominent businessman and an active member of Karachi Stock Exchange rising to the post of its President. He was also on the Local Advisory Committee of National Bank of Pakistan, Karachi Branch, and was popular in the business circles. Abdul Aziz Kaya While in Hyderabad Deccan, he joined Ittehadul Muslimeen under the leadership of Mr. Qasim Rizvi. He worked very actively for the victims of the Indian an-ny. In Karachi, on the advice of Pakistan Ambassador Haji A. Sattar Seth, he was asked to infomi all the Hujjaj about the aims and objects of the creation of Pakistan and as such Haji Aziz started his mission. Durino Haj he rendered noteworthy services to the Hujjaj. He remained involved with his business for a couple of decades and again started his social service activities and established many institutions through which he served the people. During political turmoil when Karachi was under constant curfew for several days at a stretch, he stored consumer products and food products which he supplied at concessive rates without any profit.