Government Responses to Disinformation on Social Media

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Israeli Media Self-Censorship During the Second Lebanon War

conflict & communication online, Vol. 18, No. 2, 2019 www.cco.regener-online.de ISSN 1618-0747 Sagi Elbaz & Daniel Bar-Tal Voluntary silence: Israeli media self-censorship during the Second Lebanon War Kurzfassung: Dieser Artikel beschreibt die Charakteristika der Selbstzensur im Allgemeinen, und insbesondere in den Massenmedien, im Hinblick auf Erzählungen von politischer Gewalt, einschließlich Motivation und Auswirkungen von Selbstzensur. Es präsentiert zunächst eine breite theoretische Konzeptualisierung der Selbstzensur und konzentriert sich dann auf seine mediale Praxis. Als Fallstudie wurde die Darstellung des Zweiten Libanonkrieges in den israelischen Medien untersucht. Um Selbstzensur als einen der Gründe für die Dominanz hegemonialer Erzählungen in den Medien zu untersuchen, führten die Autoren Inhaltsanalysen und Tiefeninterviews mit ehemaligen und aktuellen Journalisten durch. Die Ergebnisse der Analysen zeigen, dass israelische Journalisten die Selbstzensur weitverbreitet einsetzen, ihre Motivation, sie zu praktizieren, und die Auswirkungen ihrer Anwendung auf die Gesellschaft. Abstract: This article describes the characteristics of self-censorship in general, specifically in mass media, with regard to narratives of political violence, including motivations for and effects of practicing self-censorship. It first presents a broad theoretical conceptualization of self-censorship, and then focuses on its practice in media. The case study examined the representation of The Second Lebanon War in the Israeli national media. The authors carried out content analysis and in-depth interviews with former and current journalists in order to investigate one of the reasons for the dominance of the hegemonic narrative in the media – namely, self-censorship. Indeed, the analysis revealed widespread use of self-censorship by Israeli journalists, their motivations for practicing it, and the effects of its use on the society. -

Israel and the Alien Tort Statute

Summer 2014 No.54 JTheUSTICE magazine of the International Association of Jewish Lawyers and Jurists In this issue The International Court of Justice Adjudicating the Arab-Israel Disputes? Boycotts, Divestment, Sanctions and the Law Israel and the Alien Tort Statute Corporations and Human Rights Zivotofsky v. Kerry - A Historical Constitutional Battle Preachers of Hate and Freedom of Expression UNRWA Panel at UN IAJLJ Activities The International Association of Jewish Lawyers and Jurists Honorary President: Hadassa Ben-Itto, Judge (Ret.) (Israel) Life time Member: Irwin Cotler, Prof. (Canada) Honorary Vice Presidents: Joseph Roubache (France) Oreste Bisazza Terracini, Dr. (Italy) Executive Committee: Board of Governors: President: Irit Kohn (Israel) Irit Kohn (Israel) Haim Klugman (Israel) Avraham (Avi) D. Doron (Israel) Deputy President: Meir Rosenne, Dr. (Israel) Haim Klugman (Israel) Mirella M. Bamberger (Israel) Alyza D. Lewin (USA) Vice President and Treasurer: Marcos Arnoldo Grabivker, Judge (Argentina) Avraham (Avi) D. Doron (Israel) Maurizio Ruben (Italy) Alex Hertman (Israel) Vice President and Coordinator with Amos Shapira, Prof. (Israel) International Organizations: Avishai Sapir (Israel) Meir Rosenne, Dr. (Israel) David Pardes (Belgium) Dov Shefi, Brig. (Ret.) (Israel) Vice President and Secretary General: Edna Bekenstein, Judge (Ret.) (Israel) Mirella M. Bamberger (Israel) Edna Kaplan-Hagler, Judge (Ret.) Dr. (Israel) Efraim (Efi) Chalamish, Dr. (USA) Vice Presidents: Ethia Simha (Israel) Alyza D. Lewin (USA) Jeremy D. Margolis (USA) Marcos Arnoldo Grabivker, Judge (Argentina) Jimena Bronfman (Chile) Maurizio Ruben (Italy) Jonathan Lux (UK) Lipa Meir, Dr. (Israel) Academic Adviser: Mala Tabory, Dr. (Israel) Yaffa Zilbershats, Prof. (Israel) Maria Canals De-Cediel, Dr. (Switzerland) Meir Linzen (Israel) Representatives to the U.N. -

Digital Edition

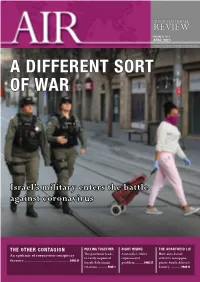

AUSTRALIA/ISRAEL REVIEW VOLUME 45 No. 4 APRIL 2020 AUSTRALIA/ISRAEL & JEWISH AFFAIRS COUNCIL A DIFFERENT SORT OF WAR Israel’s military enters the battle against coronavirus THE OTHER CONTAGION PULLING TOGETHER RIGHT RISING THE APARTHEID LIE An epidemic of coronavirus conspiracy The pandemic leads Australia’s white How anti-Israel to vastly improved supremacist activists misappro- theories ............................................... PAGE 21 Israeli-Palestinian problem ........PAGE 27 priate South Africa’s relations .......... PAGE 7 history ........... PAGE 31 WITH COMPLIMENTS NAME OF SECTION L1 26 BEATTY AVENUE ARMADALE VIC 3143 TEL: (03) 9661 8250 FAX: (03) 9661 8257 WITH COMPLIMENTS 2 AIR – April 2020 AUSTRALIA/ISRAEL VOLUME 45 No. 4 REVIEW APRIL 2020 EDITOR’S NOTE NAME OF SECTION his AIR edition focuses on the Israeli response to the extraordinary global coronavirus ON THE COVER Tpandemic – with a view to what other nations, such as Australia, can learn from the Israeli Border Police patrol Israeli experience. the streets of Jerusalem, 25 The cover story is a detailed look, by security journalist Alex Fishman, at how the IDF March 2020. Israeli authori- has been mobilised to play a part in Israel’s COVID-19 response – even while preparing ties have tightened citizens’ to meet external threats as well. In addition, Amotz Asa-El provides both a timeline of movement restrictions to Israeli measures to meet the coronavirus crisis, and a look at how Israel’s ongoing politi- prevent the spread of the coronavirus that causes the cal standoff has continued despite it. Plus, military reporter Anna Ahronheim looks at the COVID-19 disease. (Photo: Abir Sultan/AAP) cooperation the emergency has sparked between Israel and the Palestinians. -

A Threshold Crossed Israeli Authorities and the Crimes of Apartheid and Persecution WATCH

HUMAN RIGHTS A Threshold Crossed Israeli Authorities and the Crimes of Apartheid and Persecution WATCH A Threshold Crossed Israeli Authorities and the Crimes of Apartheid and Persecution Copyright © 2021 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-62313-900-1 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch defends the rights of people worldwide. We scrupulously investigate abuses, expose the facts widely, and pressure those with power to respect rights and secure justice. Human Rights Watch is an independent, international organization that works as part of a vibrant movement to uphold human dignity and advance the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Sydney, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: http://www.hrw.org APRIL 2021 ISBN: 978-1-62313-900-1 A Threshold Crossed Israeli Authorities and the Crimes of Apartheid and Persecution Map .................................................................................................................................. i Summary ......................................................................................................................... 2 Definitions of Apartheid and Persecution ................................................................................. -

Media Accountability Online in Israel. an Application of Bourdieu’S Field Theory

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Kniep, Ronja Article — Published Version Media Accountability Online in Israel. An application of Bourdieu’s field theory Global Media Journal: German Edition Provided in Cooperation with: WZB Berlin Social Science Center Suggested Citation: Kniep, Ronja (2015) : Media Accountability Online in Israel. An application of Bourdieu’s field theory, Global Media Journal: German Edition, ISSN 2196-4807, Universität Erfurt, Erfurt, Vol. 5, Iss. 2, pp. 1-32, http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:gbv:547-201500645 , http://www.globalmediajournal.de/de/2015/12/18/media-accountability-online-in-israel-an- application-of-bourdieus-field-theory/ This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/231999 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. -

Civic Identity in the Jewish State and the Changing Landscape of Israeli Constitutionalism

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont CMC Senior Theses CMC Student Scholarship 2018 Shifting Priorities? Civic Identity in the Jewish State and the Changing Landscape of Israeli Constitutionalism Mohamad Batal Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.claremont.edu/cmc_theses Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, and the Law and Politics Commons Recommended Citation Batal, Mohamad, "Shifting Priorities? Civic Identity in the Jewish State and the Changing Landscape of Israeli Constitutionalism" (2018). CMC Senior Theses. 1826. https://scholarship.claremont.edu/cmc_theses/1826 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you by Scholarship@Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in this collection by an authorized administrator. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Claremont McKenna College Shifting Priorities? Civic Identity in the Jewish State and the Changing Landscape of Israeli Constitutionalism Submitted To Professor George Thomas by Mohamad Batal for Senior Thesis Spring 2018 April 23, 2018 ii iii iv Abstract: This thesis begins with an explanation of Israel’s foundational constitutional tension—namely, that its identity as a Jewish State often conflicts with liberal- democratic principles to which it is also committed. From here, I attempt to sketch the evolution of the state’s constitutional principles, pointing to Chief Justice Barak’s “constitutional revolution” as a critical juncture where the aforementioned theoretical tension manifested in practice, resulting in what I call illiberal or undemocratic “moments.” More profoundly, by introducing Israel’s constitutional tension into the public sphere, the Barak Court’s jurisprudence forced all of the Israeli polity to confront it. My next chapter utilizes the framework of a bill currently making its way through the Knesset—Basic Law: Israel as the Nation-State of the Jewish People—in order to draw out the past and future of Israeli civic identity. -

Das Schicksal Jüdischer Juristen in Württemberg Und Hohenzollern 1933 – 1945

Regionalgruppe Südwest Das Schicksal jüdischer Juristen in Württemberg und Hohenzollern 1933 – 1945 von Alfred Marx Inhalt Guido Wolf Geleitwort zum Sonderdruck 5 Christoph Freudenreich und Uwe Rühling Vorwort zum Sonderdruck 7 Alfred Marx Das Schicksal der jüdischen Juristen in Württemberg und Hohenzollern 1933 - 1945 13 Über die Deutsch-Israelische Juristenvereinigung 89 3 Geleitwort Die Dokumentation von Landgerichtspräsident a.D. Marx über das Schicksal jüdischer Juristen in Württemberg und Hohenzollern trägt dazu bei, dass wir die Verbrechen der nationalsozialistischen Unrechtsherrschaft an Vertretern der Justiz unseres Landes auch nach über 70 Jahren nach- vollziehen können. Der vorliegende Beitrag ist ein wichtiger Bestandteil der kollektiven Sammlung unserer Vergangenheit und eine mahnende Erinnerung daran, dass wir in der Verantwor- tung unserer Geschichte stehen. Die Dokumentation ist zudem ein Aufruf, unseren Rechtsstaat allen Ortes zu ver- teidigen und uns klar gegen diejenigen zu positionieren, die versuchen ihn zu unterwandern. Der Sonderdruck des Beitrags ermöglicht es, der Öffent- lichkeit das Schicksal jüdischen Lebens ins Bewusstsein zu rufen und das Andenken derer, die dem NS-Regime zum Opfer gefallen sind, zu bewahren. Der Minister der Justiz und für Europa des Landes Baden-Württemberg Guido Wolf MdL 5 Vorwort zum Sonderdruck Anlässlich der Ausstellung „Anwalt ohne Recht“ im Amtsgericht Sigmaringen haben wir uns entschlossen, ei- ner schwer zugänglichen Veröffentlichung aus dem Jahre 1965 zu neuer Verbreitung zu verhelfen. Sie trägt den Titel „Das Schicksal der jüdischen Juristen in Württemberg und Hohenzollern 1933 - 1945“. Ihr Autor, Alfred Marx, war selbst einer der Betroffenen. Er hat überlebt – im Unter- schied zu vielen anderen Kollegen und Kolleginnen. Das Geleitwort schrieb der damalige Justizminister des Landes Baden-Württemberg, Wolfgang Haußmann. -

The Lavon Affair

Israel Military Intelligence: The Lavon Affair jewishvirtuallibrary.org/jsource/History/lavon.html Best choice for browsing Browse from Czech Republic Browse from France Browse from Sweden Browse from Canada (Summer 1954) Military Intelligence: Table of Contents | The Mossad | Targeted Assassinations The Lavon Affair is a spy story in Israel's early years that left a nasty mark on the young state, with reverberations for the following 20 years. It's name derived from Israeli Defense Minister Pinhas Lavon, though it is also referred to as " Esek HaBish" or "The Mishap". Revolving around nearly a dozen young Egyptian Jews who agreed to spy for Israel against their home country, the affair taps into a story of idealism and self-sacrifice as well as abandonment and an unwillingness to take responsibility. Due to strict censorship in Israel in the early 1950's, few knew that in the year 1954 Israeli underground cells that had been operating in Egypt were uncovered by the Egyptian police. A number of young Jews were arrested and forced to undergo a show trial. Two of them - Yosef Carmon and Max Binnet - committed suicide in prison due to the brutal interrogation methods of the Egyptian police. Two more - Dr. Moshe Marzouk of Cairo and Shmuel Azar of Alexandria - were sentenced to death and hanged in a Cairo prison. Israel glorified them as martyrs. Their memory was sanctified. Neighborhoods and gardens were named after them in Israel, as were dozens of children born in the year 1955. At the same time it was not publicly conceded that they died in the service of Israel. -

1 Schlaglicht Israel Nr. 14/19 Aktuelles Aus Israelischen

Schlaglicht Israel Nr. 14/19 Aktuelles aus israelischen Tageszeitungen 1.-31. August Die Themen dieser Ausgabe 1. Schlagabtausch im Norden ........................................................................................................................................... .1 2. In Israel nicht willkommen ............................................................................................................................................. .4 3. Countdown zum Urnengang .......................................................................................................................................... .6 4. Medienquerschnitt .......................................................................................................................................................... .9 1. Schlagabtausch im Norden The facts behind Nasrallahs threats directed at Israel steht offiziell hinter den Angriffen auf militäri- Israel sche Stützpunkte südlich von Damaskus. Ziel sei Nasrallah claimed the base that was attacked, lo- gewesen, der unmittelbaren Bedrohung durch irani- cated south of Damascus, was a Hezbollah base, sche „Killerdrohnen“ zu begegnen. Regierungschef despite the fact that his organization does not oper- Benjamin Netanyahu lobte die Operation der Luft- ate in the area. His aim was not only to remove waffe, die einen Angriff iranischer Milizen verhindert blame for his Iranian patrons, but also to clear the habe. Im Süden Beiruts sollen, Berichten der Hisbol- Syrian regime from any responsibility. The Hezbol- lah zufolge, -

Dijvmagazin 2016

Mitteilungen aus dem Verein 16. Auflage 2016 Erinnerungen an Arieh Koretz 22. Jahrestagung in Tel Aviv 23. Jahrestagung in Berlin Aus den Regionalgruppen Jewish Claims Conference Kafkas letzter Prozess Deutsch-Israelische Juristenvereinigung e.V. Inhaltsverzeichnis Vorwort der Präsidentin Brigitte Zypries …………………………………………………… 4 Nachrufe Arieh Koretz ………………………………………………………………………… 6 22. Jahrestagung in Tel Aviv Oktober 2014 Programm der Tagung …………………………………………………………………………… 16 Die Aufhebung von Gesetzen durch das Bundesverfassungsgericht ………………………… 17 Erbrecht im Vergleich Israel und Deutschland ………………………………………………… 25 Das Konzept der Law Clinics …………………………………………………………………… 26 Momentaufnahmen – ein Viertel Jahrhundert DIJV …………………………………………… 34 Heimat vielleicht – neuere Immigration zwischen Israel und Deutschland …………………… 38 Spionageprozesse in Israel ……………………………………………………………………… 51 Besuch einer israelischen Anwaltskanzlei ………………………………………………………… 54 Gedanken eines Holocaust-Überlebenden ……………………………………………………… 56 Israel und der Nahe Osten ……………………………………………………………………… 60 Protokoll der Mitgliederversammlung …………………………………………………………… 66 Satzung …………………………………………………………………………………………… 72 23. Jahrestagung in Berlin Oktober 2015 Programm der Tagung …………………………………………………………………………… 78 Eröffnungsrede des Bundesministers für Justiz und Verbraucherschutz Heiko Maas ………… 80 Rechtsprechung in Deutschland und Europa im Verfassungsverbund ………………………… 84 Das Strafvereitelungskartell ……………………………………………………………………… 86 Umgang mit Flüchtlingen – Rechtliche Aspekte im Vergleich -

Intellectual Freedom & Privacy

JOURNAL OF INTELLECTUAL FREEDOM Office for Intellectual Freedom, an Office & PRIVACY of the American Library Association A stirring summary of the essentials of intellectual freedom—misattributed to Benjamin Franklin—adorns the halls of the U.S. Capitol. CONTOURS OF INTELLECTUAL FREEDOM REVIEWS: SYLVIA 5 16 28 COOPER AND CENSORSHIP INSIDE TURCHIN: WINTER 2017 BEMAN-CAVALLARO: IN RUSSIA, BURNING LIVING THE FIRST VOL. 1 _ NO. 4 IF ISSUES IN FLORIDA BOOKS, SOCIAL ISSN 2474-7459 AMENDMENT RESPONSIBILITY IN LIS CONTENTS _ WINTER 2017 3 5 Speech and Consequences Living the First Amendment: Gordon James LaRue Conable, Madonna’s Sex, and the Monroe County (MI) Library Sylvia Turchyn 16 We’ve Come a Long Way (Baby)! Or Have We? Evolving Intellectual Freedom Issues in the US and Florida L. Bryan Cooper and A.D. Beman-Cavallaro EDITORIAL FEATURES 28 32 Garden of Broken Statues: Censorship Dateline Exploring Censorship in Russia 46 From the Bench 29 On the Burning of Books 52 Is It Legal? 30 Which Side Are You On? 71 Seven Social Responsibility Success Stories Debates in American Librarianship, 1990–2015 REVIEWS NEWS THE FIRST AMENDMENT CANNOT BE PARTITIONED. IT APPLIES TO ALL OR IT APPLIES TO NO ONE. Gordon Conable in “Living the First Amendment” _ 5 JOURNAL OF INTELLECTUAL FREEDOM AND PRIVACY _ WINTER 2017 1 WINTER 2017 _ ABOUT THE COVER _ In one of the hallways of the U.S. Capitol building, a set of murals designed by artist Allyn Cox chronicle the legislative milestones of three centuries, including the adoption of the first ten amendments to the U.S. -

Marjetka Pezdirc Terrorism Complex Final

The Terrorism Complex Submitted by Marjetka Pezdirc to the University of Exeter as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Ethno–Political Studies in January 2015 \ This thesis is available for Library use on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. I certify that all material in this thesis which is not my own work has been identified and that no material has previously been submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any other University. Signature: ………………………………………………………….. Abstract Discussing, defining and engaging with ‘terrorism’ has long been limited to the narrowly framed situations in which parties to an asymmetric conflict resort to the use of force and to the legitimacy they have in doing so. The problem with the limited understanding of ‘terrorism’ and ‘counterterrorism’ as ‘facts of objective reality’ is the lack of attention to the role of the extreme asymmetry of power in conflicts involving ‘terrorism’ that does not lend itself to analysis readily. This thesis introduces a new theoretical concept, the Terrorism Complex that signifies the complexity of power/knowledge relations and the complexity of power/knowledge practices that operate on a discursive and non-discursive level through time and are affected by the mechanisms of power that stem from the asymmetry of power between the actors involved in a conflict. The research into the Terrorism Complex involves an ontological and epistemological widening of the research focus to account for these effects of the interplay between power and knowledge on the production, construction and perception of ‘terrorism’.