Download Paper

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Self-Censorship and the First Amendment Robert A

Notre Dame Journal of Law, Ethics & Public Policy Volume 25 Article 2 Issue 1 Symposium on Censorship & the Media 1-1-2012 Self-Censorship and the First Amendment Robert A. Sedler Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.nd.edu/ndjlepp Recommended Citation Robert A. Sedler, Self-Censorship and the First Amendment, 25 Notre Dame J.L. Ethics & Pub. Pol'y 13 (2012). Available at: http://scholarship.law.nd.edu/ndjlepp/vol25/iss1/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Notre Dame Journal of Law, Ethics & Public Policy at NDLScholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Notre Dame Journal of Law, Ethics & Public Policy by an authorized administrator of NDLScholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ARTICLES SELF-CENSORSHIP AND THE FIRST AMENDMENT ROBERT A. SEDLER* I. INTRODUCTION Self-censorship refers to the decision by an individual or group to refrain from speaking and to the decision by a media organization to refrain from publishing information. Whenever an individual or group or the media engages in self-censorship, the values of the First Amendment are compromised, because the public is denied information or ideas.' It should not be sur- prising, therefore, that the principles, doctrines, and precedents of what I refer to as "the law of the First Amendment"' are designed to prevent self-censorship premised on fear of govern- mental sanctions against expression. This fear-induced self-cen- sorship will here be called "self-censorship bad." At the same time, the First Amendment also values and pro- tects a right to silence. -

Bloggers and Netizens Behind Bars: Restrictions on Internet Freedom In

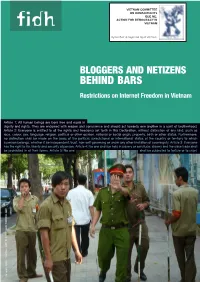

VIETNAM COMMITTEE ON HUMAN RIGHTS QUÊ ME: ACTION FOR DEMOCRACY IN VIETNAM Ủy ban Bảo vệ Quyền làm Người Việt Nam BLOGGERS AND NETIZENS BEHIND BARS Restrictions on Internet Freedom in Vietnam Article 1: All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood. Article 2: Everyone is entitled to all the rights and freedoms set forth in this Declaration, without distinction of any kind, such as race, colour, sex, language, religion, political or other opinion, national or social origin, property, birth or other status. Furthermore, no distinction shall be made on the basis of the political, jurisdictional or international status of the country or territory to which a person belongs, whether it be independent, trust, non-self-governing or under any other limitation of sovereignty. Article 3: Everyone has the right to life, liberty and security of person. Article 4: No one shall be held in slavery or servitude; slavery and the slave trade shall be prohibited in all their forms. Article 5: No one shall be subjected to torture or to cruel, January 2013 / n°603a - AFP PHOTO IAN TIMBERLAKE Cover Photo : A policeman, flanked by local militia members, tries to stop a foreign journalist from taking photos outside the Ho Chi Minh City People’s Court during the trial of a blogger in August 2011 (AFP, Photo Ian Timberlake). 2 / Titre du rapport – FIDH Introduction ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------5 -

Israel: Growing Pains at 60

Viewpoints Special Edition Israel: Growing Pains at 60 The Middle East Institute Washington, DC Middle East Institute The mission of the Middle East Institute is to promote knowledge of the Middle East in Amer- ica and strengthen understanding of the United States by the people and governments of the region. For more than 60 years, MEI has dealt with the momentous events in the Middle East — from the birth of the state of Israel to the invasion of Iraq. Today, MEI is a foremost authority on contemporary Middle East issues. It pro- vides a vital forum for honest and open debate that attracts politicians, scholars, government officials, and policy experts from the US, Asia, Europe, and the Middle East. MEI enjoys wide access to political and business leaders in countries throughout the region. Along with information exchanges, facilities for research, objective analysis, and thoughtful commentary, MEI’s programs and publications help counter simplistic notions about the Middle East and America. We are at the forefront of private sector public diplomacy. Viewpoints are another MEI service to audiences interested in learning more about the complexities of issues affecting the Middle East and US rela- tions with the region. To learn more about the Middle East Institute, visit our website at http://www.mideasti.org The maps on pages 96-103 are copyright The Foundation for Middle East Peace. Our thanks to the Foundation for graciously allowing the inclusion of the maps in this publication. Cover photo in the top row, middle is © Tom Spender/IRIN, as is the photo in the bottom row, extreme left. -

The Stored Communications Act, Gag Orders, and the First Amendment

10 BURKE (DO NOT DELETE) 12/13/2017 1:29 PM WHEN SILENCE IS NOT GOLDEN: THE STORED COMMUNICATIONS ACT, GAG ORDERS, AND THE FIRST AMENDMENT Alexandra Burke* I. INTRODUCTION Cloud computing has completely changed the landscape of information storage. Sensitive information that was once stored in file cabinets and eventually on computers is now stored remotely using web-based cloud computing services.1 The cloud’s prevalence in today’s world is undeniable, as recent studies show that nearly forty percent of all Americans2 and an estimated ninety percent of all businesses use the cloud in some capacity.3 Despite this fact, Congress has done little in recent years to protect users and providers of cloud computing services.4 What Congress has done dates back to its enactment of the Stored Communications Act (SCA) in 1986.5 Passed decades before the existence *J.D. Candidate, 2018, Baylor University School of Law; B.B.A. Accounting, 2015, Texas A&M University. I would like to extend my gratitude to each of the mentors, professors, and legal professionals who have influenced my understanding of and appreciation for the law. Specifically, I would like to thank Professor Brian Serr for his guidance in writing this article. Finally, I would like to acknowledge my family and friends, who have always shown me unwavering support. 1 See Riley v. California, 134 S. Ct. 2473, 2491 (2014) (defining cloud computing as “the capacity of Internet-connected devices to display data stored on remote servers rather than on the device itself”); see also Paul Ohm, The Fourth Amendment in a World Without Privacy, 81 MISS. -

Palestinian Forces

Center for Strategic and International Studies Arleigh A. Burke Chair in Strategy 1800 K Street, N.W. • Suite 400 • Washington, DC 20006 Phone: 1 (202) 775 -3270 • Fax : 1 (202) 457 -8746 Email: [email protected] Palestinian Forces Palestinian Authority and Militant Forces Anthony H. Cordesman Center for Strategic and International Studies [email protected] Rough Working Draft: Revised February 9, 2006 Copyright, Anthony H. Cordesman, all rights reserved. May not be reproduced, referenced, quote d, or excerpted without the written permission of the author. Cordesman: Palestinian Forces 2/9/06 Page 2 ROUGH WORKING DRAFT: REVISED FEBRUARY 9, 2006 ................................ ................................ ............ 1 THE MILITARY FORCES OF PALESTINE ................................ ................................ ................................ .......... 2 THE OSLO ACCORDS AND THE NEW ISRAELI -PALESTINIAN WAR ................................ ................................ .............. 3 THE DEATH OF ARAFAT AND THE VICTORY OF HAMAS : REDEFINING PALESTINIAN POLITICS AND THE ARAB - ISRAELI MILITARY BALANCE ................................ ................................ ................................ ................................ .... 4 THE CHANGING STRUCTURE OF PALESTINIAN AUTHORITY FORC ES ................................ ................................ .......... 5 Palestinian Authority Forces During the Peace Process ................................ ................................ ..................... 6 The -

Israeli Media Self-Censorship During the Second Lebanon War

conflict & communication online, Vol. 18, No. 2, 2019 www.cco.regener-online.de ISSN 1618-0747 Sagi Elbaz & Daniel Bar-Tal Voluntary silence: Israeli media self-censorship during the Second Lebanon War Kurzfassung: Dieser Artikel beschreibt die Charakteristika der Selbstzensur im Allgemeinen, und insbesondere in den Massenmedien, im Hinblick auf Erzählungen von politischer Gewalt, einschließlich Motivation und Auswirkungen von Selbstzensur. Es präsentiert zunächst eine breite theoretische Konzeptualisierung der Selbstzensur und konzentriert sich dann auf seine mediale Praxis. Als Fallstudie wurde die Darstellung des Zweiten Libanonkrieges in den israelischen Medien untersucht. Um Selbstzensur als einen der Gründe für die Dominanz hegemonialer Erzählungen in den Medien zu untersuchen, führten die Autoren Inhaltsanalysen und Tiefeninterviews mit ehemaligen und aktuellen Journalisten durch. Die Ergebnisse der Analysen zeigen, dass israelische Journalisten die Selbstzensur weitverbreitet einsetzen, ihre Motivation, sie zu praktizieren, und die Auswirkungen ihrer Anwendung auf die Gesellschaft. Abstract: This article describes the characteristics of self-censorship in general, specifically in mass media, with regard to narratives of political violence, including motivations for and effects of practicing self-censorship. It first presents a broad theoretical conceptualization of self-censorship, and then focuses on its practice in media. The case study examined the representation of The Second Lebanon War in the Israeli national media. The authors carried out content analysis and in-depth interviews with former and current journalists in order to investigate one of the reasons for the dominance of the hegemonic narrative in the media – namely, self-censorship. Indeed, the analysis revealed widespread use of self-censorship by Israeli journalists, their motivations for practicing it, and the effects of its use on the society. -

The Shin Beth Affair: National Security Versus the Rule of Law in the State of Israel

Loyola of Los Angeles International and Comparative Law Review Volume 11 Number 1 Article 3 1-1-1989 The Shin Beth Affair: National Security versus the Rule of Law in the State of Israel Paul F. Occhiogrosso Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/ilr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Paul F. Occhiogrosso, The Shin Beth Affair: National Security versus the Rule of Law in the State of Israel, 11 Loy. L.A. Int'l & Comp. L. Rev. 67 (1989). Available at: https://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/ilr/vol11/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews at Digital Commons @ Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Loyola of Los Angeles International and Comparative Law Review by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Shin Beth Affair: National Security Versus The Rule of Law in the State of Israel PAUL F. OCCHIOGROSSO* "Did you take them captive with your sword and bow that you would strike them down?" II Kings 6:22 I. INTRODUCTION' On the evening of April 12, 1984, four eighteen-year-old Pales- tinians from the Israeli-occupied Gaza Strip boarded a commuter bus headed south from Tel Aviv toward the coastal city of Ashkelon. About thirty-five Israelis were aboard. Shortly after boarding, the Arabs pulled knives and grenades and ordered the driver to continue past his destination and toward the Gaza Strip, saying they intended to take the bus from Gaza across the border into Egypt and from there negotiate the release of 500 Palestinians held in Israeli prisons. -

When Are Foreign Volunteers Useful? Israel's Transnational Soldiers in the War of 1948 Re-Examined

This is a repository copy of When are Foreign Volunteers Useful? Israel's Transnational Soldiers in the War of 1948 Re-examined. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/79021/ Version: WRRO with coversheet Article: Arielli, N (2014) When are Foreign Volunteers Useful? Israel's Transnational Soldiers in the War of 1948 Re-examined. Journal of Military History, 78 (2). pp. 703-724. ISSN 0899- 3718 Reuse Items deposited in White Rose Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the White Rose Research Online record for the item. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ promoting access to White Rose research papers Universities of Leeds, Sheffield and York http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/79021/ Paper: Arielli, N (2014) When are foreign volunteers useful? Israel's transnational soldiers in the war of 1948 re-examined. Journal of Military History, 78 (2). 703 - 724. White Rose Research Online [email protected] When are Foreign Volunteers Useful? Israel’s Transnational Soldiers in the War of 1948 Re-examined Nir Arielli Abstract The literature on foreign, or “transnational,” war volunteering has fo- cused overwhelmingly on the motivations and experiences of the vol- unteers. -

David Reeb: Traces of Things to Come

Bourriaud, N. Relational aesthetics, translated by S. Pleasance and F. Woods, with the participa- tion of M. Copeland. Dijon: Les presses du réels, 2002 [orig. in 1998]. Grynsztejn, M (ed.). Take your time: Olafur Eliasson. New York-London: Thames & Hudson, 2007. Mondloch, K. Screens: Viewing media installation art. Minneapolis-London: University of Minne- sota Press, 2010. Trodd, T. ‘Lack of Fit: Tacita Dean, Modernism and the Sculptural Film’, Art History, Vol. 31, No. 3, June 2008: 368-386. _____. Exhibition catalogue for Olafur Eliasson’s Riverbed, Louisiana Museum of Modern Art (20 August 2014 – 4 January 2015), 2014. Notes 21. Eliasson in Olafur Eliasson: Space is Process (H. Lundø and J. Jørgensen, 2010). 22. http://en.louisiana.dk/exhibition/olafur-eliasson 23. A more in-depth tracing of this lineage can be found in Grynsztejn 2007. 24. For more on these works in relation to cinema see Trodd 2008, p. 375. 25. Mondloch 2010, p. 26. 26. Eliasson in the exhibition catalogue 2014, p. 56. 27. Balsom 2013, p. 51. 28. Eliasson in the exhibition catalogue 2014, p. 86. 29. Bishop 2004, p. 65. 30. D. Birnbaum does offer a reading of Eliasson’s work in relation to the theories presented by Bourriaud in Grynsztejn 2007, pp. 131-143. 31. Eliasson in the exhibition catalogue 2014, p. 89. About the author Olivia Eriksson (Stockholm University David Reeb: Traces of Things to Come Leshu Torchin On 30 May 2014 the Tel Aviv Museum opened the exhibition Traces of Things to Come featuring the Israeli artist David Reeb.32 On the heels of this opening came the 10th Tel Aviv International Colloquium of Cinema and Television Studies, titled Cinematic Traces of Things to Come and focused on the mediation of impossible pasts and possible futures. -

Curriculum Vitae Dr. Ofira Gruweis-Kovalsky Contact: Kefar Tabor P.O.B 256 Israel 15241 Home Tel: 972- 4- 6765634. Mobile: 972

1 Curriculum Vitae Dr. Ofira Gruweis-Kovalsky Contact: Personal details: Kefar Tabor P.O.B 256 Israel 15241 Citizenship: Israeli Home Tel: 972- 4- 6765634. Languages: Hebrew and English Mobile: 972-52-3553384 E-mail: [email protected] [email protected] Academic rank Senior Lecturer, Zefat Academic College, Israel (2017- present) Associate researcher Herzl Institute University of Haifa, Israel (2009-present) Associate researcher at the HBI Brandeis University, USA (2015-present) Adjunct lecturer, MA and BA programs in Israel Studies, University of Haifa, Israel (2010–present). Lecturer, Zefat Academic College, Israel (2014-2017) Education 2009-2010: Post Doc. Department of Geography and Environment, Bar-Ilan University, Israel, "The History of Jerusalem as Israel Capital City". 2009: PhD, Summa cum Laude. 'Land of Israel Studies' Dept., University of Haifa. "The Vindicated and the Persecuted": Myth, Ritual, and Propaganda in the Herut Movement 1948-1965. 2006: MA, Magna cum Laude. 'Jewish History' Dept., University of Haifa. 'The Myth of the Altalena Affair and the Herut Movement'. 1980: BA, Jewish History Dept. and Land of Israel History Dept., Tel Aviv University. Israel. Certificates Mediator, Emek Yizrael Academic College, Israel (1999). Archive manager, Tel Hai Academic College and the Israel National Archives (1994). 2 Scholarly Positions: Head of the general studies division, Multidisciplinary Department, Zefat Academic College, Israel (2018-present) Senior Lecturer, Multidisciplinary Department, Zefat Academic College, Israel (2017-present) Lecturer, Multidisciplinary Department, Zefat Academic College, Israel (2014 -2017) Adjunct lecturer, Land of Israel Studies Dept., Jewish History Dept., University of Haifa. MA and BA programs (2010–present). Assistant editor, Ze’ev Jabotinsky's Ideological Writings. -

Regulations and the Rule of Law: a Look at the First Decade of Israel

Keele Law Review, Volume 2 (2021), 45-62 45 ISSN 2732-5679 ‘Hidden’ Regulations and the Rule of Law: A Look at the First decade of Israel Gal Amir* Abstract This article reviews the history of issuing regulations without due promulgation in the first decade of Israel. ‘Covert’ secondary legislation was widely used in two contexts – the ‘austerity policy’ and ‘security’ issues, both contexts intersecting in the state's attitude toward the Palestinian minority, at the time living under military rule. This article will demonstrate that, although analytically the state’s branches were committed to upholding the ‘Rule of Law’, the state used methods of covert legislation, that were in contrast to this principle. I. Introduction Regimes and states like to be associated with the term ‘Rule of Law’, as it is often associated with such terms as ‘democracy’ and ‘human rights’.1 Israel’s Declaration of Independence speaks of a state that will be democratic, egalitarian, and aspiring to the rule of law. Although the term ‘Rule of Law’ in itself is not mentioned in Israel’s Declaration of Independence, the declaration speaks of ‘… the establishment of the elected, regular authorities of the State in accordance with the Constitution which shall be adopted by the Elected Constituent Assembly not later than the 1st October 1948.’2 Even when it became clear, in the early 1950s, that a constitution would not be drafted in the foreseeable future, courts and legislators still spoke of ‘Rule of Law’ as an ideal. Following Rogers Brubaker and Frederick Cooper, one must examine the existence of the rule of law in young Israel as a ‘category of practice’ requiring reference to a citizen's daily experience, detached from the ‘analytical’ definitions of social scientists, or the high rhetoric of legislators and judges.3 Viewing ‘Rule of Law’ as a category of practice finds Israel in the first decades of its existence in a very different place than its legislators and judges aspired to be. -

Media Accountability Online in Israel. an Application of Bourdieu’S Field Theory

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Kniep, Ronja Article — Published Version Media Accountability Online in Israel. An application of Bourdieu’s field theory Global Media Journal: German Edition Provided in Cooperation with: WZB Berlin Social Science Center Suggested Citation: Kniep, Ronja (2015) : Media Accountability Online in Israel. An application of Bourdieu’s field theory, Global Media Journal: German Edition, ISSN 2196-4807, Universität Erfurt, Erfurt, Vol. 5, Iss. 2, pp. 1-32, http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:gbv:547-201500645 , http://www.globalmediajournal.de/de/2015/12/18/media-accountability-online-in-israel-an- application-of-bourdieus-field-theory/ This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/231999 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence.