Drug Consumption Databases in Europe

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Considerations in Perioperative Assessment of Valproic Acid Coagulopathy Claude Abdallah George Washington University

Himmelfarb Health Sciences Library, The George Washington University Health Sciences Research Commons Anesthesiology and Critical Care Medicine Faculty Anesthesiology and Critical Care Medicine Publications 1-2014 Considerations in perioperative assessment of valproic acid coagulopathy Claude Abdallah George Washington University Follow this and additional works at: http://hsrc.himmelfarb.gwu.edu/smhs_anesth_facpubs Part of the Anesthesia and Analgesia Commons APA Citation Abdallah, C. (2014). Considerations in perioperative assessment of valproic acid coagulopathy. Journal of Anaesthesiology Clinical Pharmacology, Volume 30, Issue 1 (). http://dx.doi.org/10.4103/0970-9185.125685 This Journal Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Anesthesiology and Critical Care Medicine at Health Sciences Research Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Anesthesiology and Critical Care Medicine Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Health Sciences Research Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. [Downloaded free from http://www.joacp.org on Tuesday, February 25, 2014, IP: 128.164.86.61] || Click here to download free Android application for this journal Revv iew Article Considerations in perioperative assessment of valproic acid coagulopathy Claude Abdallah Department of Anesthesiology, Children’s National Medical Center, The George Washington University Medical Center, NW Washington, DC, USA Abstract Valproic acid (VPA) is one of the widely prescribed antiepileptic drugs in children with multiple indications. VPA-induced coagulopathy may occur and constitute a pharmacological and practical challenge affecting pre-operative evaluation and management of patients receiving VPA therapy. This review summarizes the different studies documenting the incidence, severity and available recommendations related to this adverse effect. -

PPE Requirements Hazardous Drug Handling

This document’s purpose is only to provide general guidance. It is not a definitive interpretation for how to comply with DOSH requirements. Consult the actual NIOSH hazardous drugs list and program regulations in entirety to understand all specific compliance requirements. Minimum PPE Required Minimum PPE Required Universal (Green) - handling and disposed of using normal precautions. PPE Requirements High (Red) - double gloves, gown, eye and face protection in Low (Yellow) - handle at all times with gloves and appropriate engineering Hazardous Drug Handling addition to any necessary controls. engineering controls. Moderate (Orange) -handle at all times with gloves, gown, eye and face protection (with splash potential) and appropirate engineering controls. Tablet Open Capsule Handling only - Contained Crush/Split No alteration Crush/Split Dispensed/Common Drug Name Other Drug Name Additional Information (Formulation) and (NIOSH CATEGORY #) Minimum PPE Minimum PPE Minimum PPE Minimum PPE Required required required required abacavir (susp) (2) ziagen/epzicom/trizivir Low abacavir (tablet) (2) ziagen/epzicom/trizivir Universal Low Moderate acitretin (capsule) (3) soriatane Universal Moderate anastrazole (tablet) (1) arimidex Low Moderate High android (capsule) (3) methyltestosterone Universal Moderate apomorphine (inj sq) (2) apomorphine Moderate arthotec/cytotec (tablet) (3) diclofenac/misoprostol Universal Low Moderate astagraf XL (capsule) (2) tacrolimus Universal do not open avordart (capsule) (3) dutasteride Universal Moderate azathioprine -

With LAMOTRIGINE IN

were independent of seizure type. Cardiac abnormalities occurring in epilepsy with GTCS may potentially facilitate sudden cardiac death (SUDEP). ETHOSUXIMIDE, VALPROIC ACID, AND LAMOTRIGINE IN CHILDHOOD ABSENCE EPILEPSY Efficacy, tolerability, and neuropsychological effects of ethosuximide, valproic acid, and lamotrigine in children with newly diagnosed childhood absence epilepsy were compared in a double-blind, randomized, controlled clinical trial performed at six centers in the US and organized as a Study Group. Drug doses were incrementally increased until freedom from seizures or highest tolerable dose was reached, Primary outcome was freedom from treatment failure after 16 weeks therapy, and secondary outcome was attentional dysfunction. In a total of 453 children, the freedom-from-failure rates after 16 weeks were similar for ethosuximide (53%) and valproic acid (58%), and higher than the rate for lamotrigine (29%) (P<0.001). Attentional dysfunction was more common with valproic acid (49%) than with ethosuximide (33%) (P=0.03). (Glauser TA, Cnaan A, Shinnar S, et al. Ethosuximide, valproic acid, and lamotrigine in childhood absence epilepsy. N Engl J Med March 4 2010;362:790-799). (Reprints: Dr Tracy A Glauser, Cincinnati Children's Hospital, 3333 Burnett Ave, MLC 2015, Cincinnati, OH 45229. E- mail: [email protected]). COMMENT. "Older is better," is the conclusion of Vining EPG, in an editorial (N Engl J Med 2010;362:843-845). As generally accepted in US practice and confirmed by the above controlled trial, ethosuximide from the 1950s is the optimal initial therapy for childhood absence epilepsy without GTCS. Ethosuximide is equal to valproic acid in seizure control and superior in effects on attention. -

Management of Status Epilepticus

Published online: 2019-11-21 THIEME Review Article 267 Management of Status Epilepticus Ritesh Lamsal1 Navindra R. Bista1 1Department of Anaesthesiology, Tribhuvan University Teaching Address for correspondence Ritesh Lamsal, MD, DM, Department Hospital, Institute of Medicine, Tribhuvan University, Nepal of Anaesthesiology, Tribhuvan University Teaching Hospital, Institute of Medicine, Tribhuvan University,Kathmandu, Nepal (e-mail: [email protected]). J Neuroanaesthesiol Crit Care 2019;6:267–274 Abstract Status epilepticus (SE) is a life-threatening neurologic condition that requires imme- diate assessment and intervention. Over the past few decades, the duration of seizure Keywords required to define status epilepticus has shortened, reflecting the need to start thera- ► convulsive status py without the slightest delay. The focus of this review is on the management of con- epilepticus vulsive and nonconvulsive status epilepticus in critically ill patients. Initial treatment ► neurocritical care of both forms of status epilepticus includes immediate assessment and stabilization, ► nonconvulsive status and administration of rapidly acting benzodiazepine therapy followed by nonbenzodi- epilepticus azepine antiepileptic drug. Refractory and super-refractory status epilepticus (RSE and ► refractory status SRSE) pose a lot of therapeutic problems, necessitating the administration of contin- epilepticus uous infusion of high doses of anesthetic agents, and carry a high risk of debilitating ► status epilepticus morbidity as well as mortality. ► super-refractory sta- tus epilepticus Introduction occur after 30 minutes of seizure activity. However, this working definition did not indicate the need to immediately Status epilepticus (SE) is a medical and neurologic emergency commence treatment and that permanent neuronal injury that requires immediate evaluation and treatment. It is associat- could occur by the time a clinical diagnosis of SE was made. -

In Silico Methods for Drug Repositioning and Drug-Drug Interaction Prediction

In silico Methods for Drug Repositioning and Drug-Drug Interaction Prediction Pathima Nusrath Hameed ORCID: 0000-0002-8118-9823 Submitted in total fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Mechanical Engineering THE UNIVERSITY OF MELBOURNE May 2018 Copyright © 2018 Pathima Nusrath Hameed All rights reserved. No part of the publication may be reproduced in any form by print, photoprint, microfilm or any other means without written permission from the author. Abstract Drug repositioning and drug-drug interaction (DDI) prediction are two fundamental ap- plications having a large impact on drug development and clinical care. Drug reposi- tioning aims to identify new uses for existing drugs. Moreover, understanding harmful DDIs is essential to enhance the effects of clinical care. Exploring both therapeutic uses and adverse effects of drugs or a pair of drugs have significant benefits in pharmacology. The use of computational methods to support drug repositioning and DDI prediction en- able improvements in the speed of drug development compared to in vivo and in vitro methods. This thesis investigates the consequences of employing a representative training sam- ple in achieving better performance for DDI classification. The Positive-Unlabeled Learn- ing method introduced in this thesis aims to employ representative positives as well as reliable negatives to train the binary classifier for inferring potential DDIs. Moreover, it explores the importance of a finer-grained similarity metric to represent the pairwise drug similarities. Drug repositioning can be approached by new indication detection. In this study, Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) classification is used as the primary source to determine the indications/therapeutic uses of drugs for drug repositioning. -

AHFS Pharmacologic-Therapeutic Classification System

AHFS Pharmacologic-Therapeutic Classification System Abacavir 48:24 - Mucolytic Agents - 382638 8:18.08.20 - HIV Nucleoside and Nucleotide Reverse Acitretin 84:92 - Skin and Mucous Membrane Agents, Abaloparatide 68:24.08 - Parathyroid Agents - 317036 Aclidinium Abatacept 12:08.08 - Antimuscarinics/Antispasmodics - 313022 92:36 - Disease-modifying Antirheumatic Drugs - Acrivastine 92:20 - Immunomodulatory Agents - 306003 4:08 - Second Generation Antihistamines - 394040 Abciximab 48:04.08 - Second Generation Antihistamines - 394040 20:12.18 - Platelet-aggregation Inhibitors - 395014 Acyclovir Abemaciclib 8:18.32 - Nucleosides and Nucleotides - 381045 10:00 - Antineoplastic Agents - 317058 84:04.06 - Antivirals - 381036 Abiraterone Adalimumab; -adaz 10:00 - Antineoplastic Agents - 311027 92:36 - Disease-modifying Antirheumatic Drugs - AbobotulinumtoxinA 56:92 - GI Drugs, Miscellaneous - 302046 92:20 - Immunomodulatory Agents - 302046 92:92 - Other Miscellaneous Therapeutic Agents - 12:20.92 - Skeletal Muscle Relaxants, Miscellaneous - Adapalene 84:92 - Skin and Mucous Membrane Agents, Acalabrutinib 10:00 - Antineoplastic Agents - 317059 Adefovir Acamprosate 8:18.32 - Nucleosides and Nucleotides - 302036 28:92 - Central Nervous System Agents, Adenosine 24:04.04.24 - Class IV Antiarrhythmics - 304010 Acarbose Adenovirus Vaccine Live Oral 68:20.02 - alpha-Glucosidase Inhibitors - 396015 80:12 - Vaccines - 315016 Acebutolol Ado-Trastuzumab 24:24 - beta-Adrenergic Blocking Agents - 387003 10:00 - Antineoplastic Agents - 313041 12:16.08.08 - Selective -

Therapeutic Class Overview Anticonvulsants

Therapeutic Class Overview Anticonvulsants INTRODUCTION Epilepsy is a disease of the brain defined by any of the following (Fisher et al 2014): ○ At least 2 unprovoked (or reflex) seizures occurring > 24 hours apart; ○ 1 unprovoked (or reflex) seizure and a probability of further seizures similar to the general recurrence risk (at least 60%) after 2 unprovoked seizures, occurring over the next 10 years; ○ Diagnosis of an epilepsy syndrome. Types of seizures include generalized seizures, focal (partial) seizures, and status epilepticus (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC] 2018, Epilepsy Foundation 2016). ○ Generalized seizures affect both sides of the brain and include: . Tonic-clonic (grand mal): begin with stiffening of the limbs, followed by jerking of the limbs and face . Myoclonic: characterized by rapid, brief contractions of body muscles, usually on both sides of the body at the same time . Atonic: characterized by abrupt loss of muscle tone; they are also called drop attacks or akinetic seizures and can result in injury due to falls . Absence (petit mal): characterized by brief lapses of awareness, sometimes with staring, that begin and end abruptly; they are more common in children than adults and may be accompanied by brief myoclonic jerking of the eyelids or facial muscles, a loss of muscle tone, or automatisms. ○ Focal seizures are located in just 1 area of the brain and include: . Simple: affect a small part of the brain; can affect movement, sensations, and emotion, without a loss of consciousness . Complex: affect a larger area of the brain than simple focal seizures and the patient loses awareness; episodes typically begin with a blank stare, followed by chewing movements, picking at or fumbling with clothing, mumbling, and performing repeated unorganized movements or wandering; they may also be called “temporal lobe epilepsy” or “psychomotor epilepsy” . -

Pharmacokinetic Drug–Drug Interactions Among Antiepileptic Drugs, Including CBD, Drugs Used to Treat COVID-19 and Nutrients

International Journal of Molecular Sciences Review Pharmacokinetic Drug–Drug Interactions among Antiepileptic Drugs, Including CBD, Drugs Used to Treat COVID-19 and Nutrients Marta Kara´zniewicz-Łada 1 , Anna K. Główka 2 , Aniceta A. Mikulska 1 and Franciszek K. Główka 1,* 1 Department of Physical Pharmacy and Pharmacokinetics, Poznan University of Medical Sciences, 60-781 Pozna´n,Poland; [email protected] (M.K.-Ł.); [email protected] (A.A.M.) 2 Department of Bromatology, Poznan University of Medical Sciences, 60-354 Pozna´n,Poland; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +48-(0)61-854-64-37 Abstract: Anti-epileptic drugs (AEDs) are an important group of drugs of several generations, rang- ing from the oldest phenobarbital (1912) to the most recent cenobamate (2019). Cannabidiol (CBD) is increasingly used to treat epilepsy. The outbreak of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic in 2019 created new challenges in the effective treatment of epilepsy in COVID-19 patients. The purpose of this review is to present data from the last few years on drug–drug interactions among of AEDs, as well as AEDs with other drugs, nutrients and food. Literature data was collected mainly in PubMed, as well as google base. The most important pharmacokinetic parameters of the chosen 29 AEDs, mechanism of action and clinical application, as well as their biotransformation, are presented. We pay a special attention to the new potential interactions of the applied first-generation AEDs (carba- Citation: Kara´zniewicz-Łada,M.; mazepine, oxcarbazepine, phenytoin, phenobarbital and primidone), on decreased concentration Główka, A.K.; Mikulska, A.A.; of some medications (atazanavir and remdesivir), or their compositions (darunavir/cobicistat and Główka, F.K. -

Classification of Medicinal Drugs and Driving: Co-Ordination and Synthesis Report

Project No. TREN-05-FP6TR-S07.61320-518404-DRUID DRUID Driving under the Influence of Drugs, Alcohol and Medicines Integrated Project 1.6. Sustainable Development, Global Change and Ecosystem 1.6.2: Sustainable Surface Transport 6th Framework Programme Deliverable 4.4.1 Classification of medicinal drugs and driving: Co-ordination and synthesis report. Due date of deliverable: 21.07.2011 Actual submission date: 21.07.2011 Revision date: 21.07.2011 Start date of project: 15.10.2006 Duration: 48 months Organisation name of lead contractor for this deliverable: UVA Revision 0.0 Project co-funded by the European Commission within the Sixth Framework Programme (2002-2006) Dissemination Level PU Public PP Restricted to other programme participants (including the Commission x Services) RE Restricted to a group specified by the consortium (including the Commission Services) CO Confidential, only for members of the consortium (including the Commission Services) DRUID 6th Framework Programme Deliverable D.4.4.1 Classification of medicinal drugs and driving: Co-ordination and synthesis report. Page 1 of 243 Classification of medicinal drugs and driving: Co-ordination and synthesis report. Authors Trinidad Gómez-Talegón, Inmaculada Fierro, M. Carmen Del Río, F. Javier Álvarez (UVa, University of Valladolid, Spain) Partners - Silvia Ravera, Susana Monteiro, Han de Gier (RUGPha, University of Groningen, the Netherlands) - Gertrude Van der Linden, Sara-Ann Legrand, Kristof Pil, Alain Verstraete (UGent, Ghent University, Belgium) - Michel Mallaret, Charles Mercier-Guyon, Isabelle Mercier-Guyon (UGren, University of Grenoble, Centre Regional de Pharmacovigilance, France) - Katerina Touliou (CERT-HIT, Centre for Research and Technology Hellas, Greece) - Michael Hei βing (BASt, Bundesanstalt für Straßenwesen, Germany). -

1-(4-Amino-Cyclohexyl)

(19) & (11) EP 1 598 339 B1 (12) EUROPEAN PATENT SPECIFICATION (45) Date of publication and mention (51) Int Cl.: of the grant of the patent: C07D 211/04 (2006.01) C07D 211/06 (2006.01) 24.06.2009 Bulletin 2009/26 C07D 235/24 (2006.01) C07D 413/04 (2006.01) C07D 235/26 (2006.01) C07D 401/04 (2006.01) (2006.01) (2006.01) (21) Application number: 05014116.7 C07D 401/06 C07D 403/04 C07D 403/06 (2006.01) A61K 31/44 (2006.01) A61K 31/48 (2006.01) A61K 31/415 (2006.01) (22) Date of filing: 18.04.2002 A61K 31/445 (2006.01) A61P 25/04 (2006.01) (54) 1-(4-AMINO-CYCLOHEXYL)-1,3-DIHYDRO-2H-BENZIMIDAZOLE-2-ONE DERIVATIVES AND RELATED COMPOUNDS AS NOCICEPTIN ANALOGS AND ORL1 LIGANDS FOR THE TREATMENT OF PAIN 1-(4-AMINO-CYCLOHEXYL)-1,3-DIHYDRO-2H-BENZIMIDAZOLE-2-ON DERIVATE UND VERWANDTE VERBINDUNGEN ALS NOCICEPTIN ANALOGE UND ORL1 LIGANDEN ZUR BEHANDLUNG VON SCHMERZ DERIVÉS DE LA 1-(4-AMINO-CYCLOHEXYL)-1,3-DIHYDRO-2H-BENZIMIDAZOLE-2-ONE ET COMPOSÉS SIMILAIRES POUR L’UTILISATION COMME ANALOGUES DU NOCICEPTIN ET LIGANDES DU ORL1 POUR LE TRAITEMENT DE LA DOULEUR (84) Designated Contracting States: • Victory, Sam AT BE CH CY DE DK ES FI FR GB GR IE IT LI LU Oak Ridge, NC 27310 (US) MC NL PT SE TR • Whitehead, John Designated Extension States: Newtown, PA 18940 (US) AL LT LV MK RO SI (74) Representative: Maiwald, Walter (30) Priority: 18.04.2001 US 284666 P Maiwald Patentanwalts GmbH 18.04.2001 US 284667 P Elisenhof 18.04.2001 US 284668 P Elisenstrasse 3 18.04.2001 US 284669 P 80335 München (DE) (43) Date of publication of application: (56) References cited: 23.11.2005 Bulletin 2005/47 EP-A- 0 636 614 EP-A- 0 990 653 EP-A- 1 142 587 WO-A-00/06545 (62) Document number(s) of the earlier application(s) in WO-A-00/08013 WO-A-01/05770 accordance with Art. -

Dorset Medicines Advisory Group

DORSET CARDIOLOGY WORKING GROUP GUIDELINE FOR CALCIUM CHANNEL BLOCKERS IN HYPERTENSION SUMMARY The pan-Dorset cardiology working group continues to recommend the use of amlodipine (a third generation dihydropyridine calcium-channel blocker) as first choice calcium channel blocker on the pan-Dorset formulary for hypertension. Lercanidipine is second choice, lacidipine third choice and felodipine is fourth choice. This is due to preferable side effect profiles in terms of ankle oedema and relative costs of the preparations. Note: where angina is the primary indication or is a co-morbidity prescribers must check against the specific product characteristics (SPC) for an individual drug to confirm this is a licensed indication. N.B. Lacidipine and lercandipine are only licensed for use in hypertension. Chapter 02.06.02 CCBs section of the Formulary has undergone an evidence-based review. A comprehensive literature search was carried out on NHS Evidence, Medline, EMBASE, Cochrane Database, and UK Duets. This was for recent reviews or meta-analyses on calcium channel blockers from 2009 onwards (comparative efficacy and side effects) and randomised controlled trials (RCTs). REVIEW BACKGROUND Very little good quality evidence exists. No reviews, meta-analyses or RCTs were found covering all calcium channel blockers currently on the formulary. Another limitation was difficulty obtaining full text original papers for some of the references therefore having to use those from more obscure journals instead. Some discrepancies exist between classification of generations of dihydropyridine CCBs, depending upon the year of publication of the reference/authors’ interpretation. Dihydropyridine (DHP) CCBs tend to be more potent vasodilators than non-dihydropyridine (non-DHP) CCBs (diltiazem, verapamil), but the latter have greater inotropic effects. -

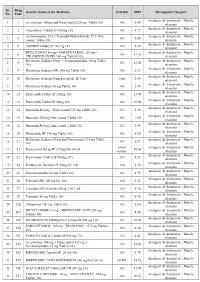

PMBJP Product.Pdf

Sr. Drug Generic Name of the Medicine Unit Size MRP Therapeutic Category No. Code Analgesic & Antipyretic / Muscle 1 1 Aceclofenac 100mg and Paracetamol 325 mg Tablet 10's 10's 8.00 relaxants Analgesic & Antipyretic / Muscle 2 2 Aceclofenac Tablets IP 100mg 10's 10's 4.37 relaxants Acetaminophen 325 + Tramadol Hydrochloride 37.5 film Analgesic & Antipyretic / Muscle 3 4 10's 8.00 coated Tablet 10's relaxants Analgesic & Antipyretic / Muscle 4 5 ASPIRIN Tablets IP 150 mg 14's 14's 2.70 relaxants DICLOFENAC 50 mg+ PARACETAMOL 325 mg+ Analgesic & Antipyretic / Muscle 5 6 10's 11.30 CHLORZOXAZONE 500 mg Tablets 10's relaxants Diclofenac Sodium 50mg + Serratiopeptidase 10mg Tablet Analgesic & Antipyretic / Muscle 6 8 10's 12.00 10's relaxants Analgesic & Antipyretic / Muscle 7 9 Diclofenac Sodium (SR) 100 mg Tablet 10's 10's 6.12 relaxants Analgesic & Antipyretic / Muscle 8 10 Diclofenac Sodium 25mg per ml Inj. IP 3 ml 3 ml 2.00 relaxants Analgesic & Antipyretic / Muscle 9 11 Diclofenac Sodium 50 mg Tablet 10's 10's 2.90 relaxants Analgesic & Antipyretic / Muscle 10 12 Etoricoxilb Tablets IP 120mg 10's 10's 33.00 relaxants Analgesic & Antipyretic / Muscle 11 13 Etoricoxilb Tablets IP 90mg 10's 10's 25.00 relaxants Analgesic & Antipyretic / Muscle 12 14 Ibuprofen 400 mg + Paracetamol 325 mg Tablet 10's 15's 5.50 relaxants Analgesic & Antipyretic / Muscle 13 15 Ibuprofen 200 mg film coated Tablet 10's 10's 1.80 relaxants Analgesic & Antipyretic / Muscle 14 16 Ibuprofen 400 mg film coated Tablet 10's 15's 3.50 relaxants Analgesic & Antipyretic