Tim Lawrence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

EDM (Dance Music): Disco, Techno, House, Raves… ANTHRO 106 2018

EDM (Dance Music): Disco, Techno, House, Raves… ANTHRO 106 2018 Rebellion, genre, drugs, freedom, unity, sex, technology, place, community …………………. Disco • Disco marked the dawn of dance-based popular music. • Growing out of the increasingly groove-oriented sound of early '70s and funk, disco emphasized the beat above anything else, even the singer and the song. • Disco was named after discotheques, clubs that played nothing but music for dancing. • Most of the discotheques were gay clubs in New York • The seventies witnessed the flowering of gay clubbing, especially in New York. For the gay community in this decade, clubbing became 'a religion, a release, a way of life'. The camp, glam impulses behind the upsurge in gay clubbing influenced the image of disco in the mid-Seventies so much that it was often perceived as the preserve of three constituencies - blacks, gays and working-class women - all of whom were even less well represented in the upper echelons of rock criticism than they were in society at large. • Before the word disco existed, the phrase discotheque records was used to denote music played in New York private rent or after hours parties like the Loft and Better Days. The records played there were a mixture of funk, soul and European imports. These "proto disco" records are the same kind of records that were played by Kool Herc on the early hip hop scene. - STARS and CLUBS • Larry Levan was the first DJ-star and stands at the crossroads of disco, house and garage. He was the legendary DJ who for more than 10 years held court at the New York night club Paradise Garage. -

Discourse on Disco

Chapter 1: Introduction to the cultural context of electronic dance music The rhythmic structures of dance music arise primarily from the genre’s focus on moving dancers, but they reveal other influences as well. The poumtchak pattern has strong associations with both disco music and various genres of electronic dance music, and these associations affect the pattern’s presence in popular music in general. Its status and musical role there has varied according to the reputation of these genres. In the following introduction I will not present a complete history of related contributors, places, or events but rather examine those developments that shaped prevailing opinions and fields of tension within electronic dance music culture in particular. This culture in turn affects the choices that must be made in dance music production, for example involving the poumtchak pattern. My historical overview extends from the 1970s to the 1990s and covers predominantly the disco era, the Chicago house scene, the acid house/rave era, and the post-rave club-oriented house scene in England.5 The disco era of the 1970s DISCOURSE ON DISCO The image of John Travolta in his disco suit from the 1977 motion picture Saturday Night Fever has become an icon of the disco era and its popularity. Like Blackboard Jungle and Rock Around the Clock two decades earlier, this movie was an important vehicle for the distribution of a new dance music culture to America and the entire Western world, and the impact of its construction of disco was gigantic.6 It became a model for local disco cultures around the world and comprised the core of a common understanding of disco in mainstream popular music culture. -

Joseph Gallucci Prof. Howard Besser Intro to Moving Image Archiving And

Joseph Gallucci Prof. Howard Besser Intro to Moving Image Archiving and Preservation 9 December 2008 Our Sequined Heritage: A Night at the Gallery and the Audiovisual Record of New York's Underground Dance Clubs In the popular consciousness, at least among those who lived through the era and into the following generation, the word "disco" registers in the mind as something ersatz, plastic, disposable, chintzy, and, as the implication of such labels suggests, ultimately insignificant. A certain set of signifiers are automatically associated with discotheques: John Travolta's character in Saturday Night Fever, suited all in white with gold chains adorning an exposed, hirsute chest; glamorous celebrities engaging in unspeakably decadent behavior; and of course, the omnipresent music that seemingly refuses to die, falsetto male voices (save for Barry White) and belting divas over bouncy, string-laden, and percussive pop songs that are more often than not described as "guilty pleasures" by the very people who sing along to them at karaoke bars or dance to them at weddings. It It is telling that on Wikipedia, disco belongs to the subject category "1970s fads" (its arguable spiritual descendant, new wave, is similarly listed as a "1980s fad"). Punk, on the other hand, which emerged roughly simultaneously with disco's ascendance to the pop culture stratosphere, manages to escape this vaguely derogatory classification, perhaps because it was never embraced to quite the extent that disco was and cannot technically qualify as a "fad." However much these archetypes have persisted, it should be stated that little of it was rooted in reality: Saturday Night Fever, for instance, was based on an article written by Nik Cohn for New York Magazine that, while not too far off from the truth vis-à-vis the Italian-American inner-city working-class preoccupation with disco, was mostly fabricated (Laurino 137). -

The Loft Cinema Film Guide

loftcinema.org THE LOFT CINEMA Showtimes: FILM GUIDE 520-795-7777 JUNE 2019 WWW.LOFTCINEMA.ORG See what films are playing next, buy tickets, look up showtimes & much more! ENJOY BEER & WINE AT THE LOFT CINEMA! We also offer Fresco Pizza*, Tucson Tamale Company Tamales, Burritos from Tumerico, Ethiopian Wraps from JUNE 2019 Cafe Desta and Sandwiches from the 4th Ave. Deli, along with organic popcorn, craft chocolate bars, vegan LOFT MEMBERSHIPS 5 cookies and more! *Pizza served after 5pm daily. SPECIAL ENGAGEMENTS 6-27 SOLAR CINEMA 6, 9, 14, 17, 21 NATIONAL THEATRE LIVE 10 BEER OF THE MONTH: LOFT JR. 11 SUMMERFEST ESSENTIAL CINEMA 13 SIERRA NEVADA BREWING CO. LOFT STAFF SELECTS 19 ONLY $3.50 ALL THROUGH JUNE! COMMUNITY RENTALS 23 REEL READS SELECTION 25 CLOSED CAPTIONS & AUDIO DESCRIPTIONS! THE FILMS OF CHER 26-27 The Loft Cinema offers Closed Captions and Audio NEW FILMS 32-43 Descriptions for films whenever they are available. Check our MONDO MONDAYS 46 website to see which films offer this technology. CULT CLASSICS 47 FILM GUIDES ARE AVAILABLE AT: FREE MEMBERS SCREENING • 1702 Craft Beer & • Epic Cafe • R-Galaxy Pizza BE NATURAL... • Ermanos • Raging Sage (SEE PAGE 37) • aLoft Hotel • Fantasy Comics • Rocco’s Little FRIDAY, JUNE 14 AT 7:00PM • Antigone Books • First American Title Chicago • Aqua Vita • Frominos • SW University of • Black Crown Visual Arts REGULAR ADMISSION PRICES • Heroes & Villains Coffee • Shot in the Dark $9.75 - Adult | $7.25 - Matinee* • Hotel Congress $8.00 - Student, Teacher, Military • Black Rose Tattoo Cafe • Humanities $6.75 - Senior (65+) or Child (12 & under) • Southern AZ AIDS $6.00 - Loft Members • Bookman’s Seminars Foundation *MATINEE: ANY SCREENING BEFORE 4:00PM • Bookstop • Jewish Community • The Historic Y Tickets are available to purchase online at: • Borderlands Center • Time Market loftcinema.org/showtimes Brewery • KXCI or by calling: 520-795-0844 • Tucson Hop Shop • Brooklyn Pizza • La Indita • UA Media Arts Phone & Web orders are subject to a • Cafe Luce • Maynard’s Market $1 surcharge. -

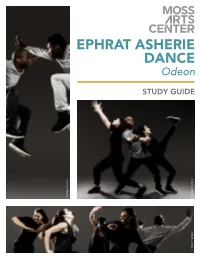

EPHRAT ASHERIE DANCE Odeon

EPHRAT ASHERIE DANCE Odeon STUDY GUIDE ©Matthew Murphy ©Matthew Murphy ©Matthew Murphy Wednesday, March 31, 2021, 10 AM EDT PROGRAM Odeon Choreographer: Ephrat Asherie, in collaboration with Ephrat Asherie Dance Music: Ernesto Nazareth Musical Direction: Ehud Asherie Lighting Design: Kathy Kaufmann Costume Design: Mark Eric We gratefully acknowledge and thank the Joyce Theater’s School & Family Programs for generously allowing the Moss Arts Center’s use and adaptation of its Ephrat Asherie Dance Odeon Resource and Reference Guide. Heather McCartney, director | Rachel Thorne Germond, associate EPHRAT ASHERIE DANCE “Ms. Asherie’s movement phrases—compact bursts of choreography with rapid-fire changes in rhythm and gestural articulation—bubble up and dissipate, quickly paving the way for something new.” –The New York Times THE COMPANY Ephrat Asherie Dance (EAD) is a dance company rooted in Black and Latinx vernacular dance. Dedicated to exploring the inherent complexities of various street and club dances, including breaking, hip-hop, house, and vogue, EAD investigates the expansive narrative qualities of these forms as a means to tell stories, develop innovative imagery, and find new modes of expression. EAD’s first evening-length work,A Single Ride, earned two Bessie nominations in 2013 for Outstanding Emerging Choreographer and Outstanding Sound Design by Marty Beller. The company has presented work at Apollo Theater, Columbia College, Dixon Place, FiraTarrega, Works & Process at the Guggenheim, Jacob’s Pillow Dance Festival, the Joyce Theater, La MaMa, River to River Festival, New York Live Arts, Summerstage, and The Yard, among others. ARTISTIC DIRECTOR Ephrat “Bounce” Asherie is a New York City-based b-girl, performer, choreographer, and director and a 2016 Bessie Award Winner for Innovative Achievement in Dance. -

Aliens, Afropsychedelia and Psyculture

The Vibe of the Exiles: Aliens, Afropsychedelia and Psyculture Feature Article Graham St John Griffith University (Australia) Abstract This article offers detailed comment on thevibe of the exiles, a socio-sonic aesthetic infused with the sensibility of the exile, of compatriotism in expatriation, a characteristic of psychedelic electronica from Goatrance to psytrance and beyond (i.e. psyculture). The commentary focuses on an emancipatory artifice which sees participants in the psyculture continuum adopt the figure of the alien in transpersonal and utopian projects. Decaled with the cosmic liminality of space exploration, alien encounter and abduction repurposed from science fiction, psychedelic event-culture cultivates posthumanist pretentions resembling Afrofuturist sensibilities that are identified with, appropriated and reassembled by participants. Offering a range of examples, among them Israeli psychedelic artists bent on entering another world, the article explores the interface of psyculture and Afrofuturism. Sharing a theme central to cosmic jazz, funk, rock, dub, electro, hip-hop and techno, from the earliest productions, Israeli and otherwise, Goatrance, assumed an off-world trajectory, and a concomitant celebration of difference, a potent otherness signified by the alien encounter, where contact and abduction become driving narratives for increasingly popular social aesthetics. Exploring the different orbits from which mystics and ecstatics transmit visions of another world, the article, then, focuses on the socio- sonic aesthetics of the dance floor, that orgiastic domain in which a multitude of “freedoms” are performed, mutant utopias propagated, and alien identities danced into being. Keywords: alien-ation; psyculture; Afrofuturism; posthumanism; psytrance; exiles; aliens; vibe Graham St John is a cultural anthropologist and researcher of electronic dance music cultures and festivals. -

New York State Multiple Dwelling Law Article 1 Introductory Provisions; Definitions

NEW YORK STATE MULTIPLE DWELLING LAW ARTICLE 1 INTRODUCTORY PROVISIONS; DEFINITIONS §1. Short title. This chapter shall be known as the "multiple dwelling law." §2. Legislative finding. It is hereby declared that intensive occupation of multiple dwelling sites, overcrowding of multiple dwelling rooms, inadequate provision for light and air, and insufficient protection against the defective provision for escape from fire, and improper sanitation of multiple dwellings in certain areas of the state are a menace to the health, safety, morals, welfare, and reasonable comfort of the citizens of the state; and that the establishment and maintenance of proper housing standards requiring sufficient light, air, sanitation and protection from fire hazards are essential to the public welfare. Therefore the provisions hereinafter prescribed are enacted and their necessity in the public interest is hereby declared as a matter of legislative determination. §3. Application to cities, towns and villages. 1. This chapter shall apply to all cities with a population of three hundred twenty-five thousand or more. 2. The legislative body of any other city, town or village may adopt the provisions of this chapter and make the same applicable to dwellings within the limits of such city, town or village by the passage of a local law or ordinance adopting the same; and upon the passage of such local law or ordinance all of the provisions of articles one, two, three, four, five, ten and eleven and such sections or parts of sections of the other articles of this chapter as such local law or ordinance shall enumerate, shall apply to such city, town or village from the date stated in such law or ordinance. -

Love Saves the Day

LOVE SAVES THE DAY DAVID MANCUSO AND THE LOFT BY TIM LAWRENCE 002 Like a soup or a bicycle or Wikipedia, the Loft is an amal- ophy around the psychedelic experience that would in- 003 gamation of parts that are weak in isolation, but joyful, rev- form the way records were selected at the Loft, was anoth- elatory and powerful when joined together. The first in- er echo that resonated at the Broadway Loft. Co-existing gredient is the desire of a group of friends to want to get with Leary, the civil rights, the gay liberation, feminist and together and have some fun. The second element is the the anti-war movements of the 1960s were manifest in discovery of a room that has good acoustics and is comfort- the egalitarian, rainbow coalition, come-as-you-are ethos able for dancing, which means it should have rectangular of the Loft. And the Harlem rent parties of the 1920s, in dimensions, a reasonably high ceiling, a nice wooden floor which economically underprivileged African American and the possibility of privacy. The next building block is tenants put on shindigs in order to help raise some money the sound system, which is most effective when it is sim- (through "donations" made at the door) to pay the rent, ple, clean and warm, and when it isn't pushed more than a established a template for putting on a private party that fraction above 100 decibels (so that people's ears don't be- didn't require a liquor or cabaret license and could ac- come tired or even damaged). -

From Disco to Electronic Music: Following the Evolution of Dance Culture Through Music Genres, Venues, Laws, and Drugs

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont CMC Senior Theses CMC Student Scholarship 2010 From Disco to Electronic Music: Following the Evolution of Dance Culture Through Music Genres, Venues, Laws, and Drugs. Ambrose Colombo Claremont McKenna College Recommended Citation Colombo, Ambrose, "From Disco to Electronic Music: Following the Evolution of Dance Culture Through Music Genres, Venues, Laws, and Drugs." (2010). CMC Senior Theses. Paper 83. http://scholarship.claremont.edu/cmc_theses/83 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you by Scholarship@Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in this collection by an authorized administrator. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Table of Contents I. Introduction 1 II. Disco: New York, Philadelphia, Chicago, and Detroit in the 1970s 3 III. Sound and Technology 13 IV. Chicago House 17 V. Drugs and the UK Acid House Scene 24 VI. Acid house parties: the precursor to raves 32 VII. New genres and exportation to the US 44 VIII. Middle America and Large Festivals 52 IX. Conclusion 57 I. Introduction There are many beginnings to the history of Electronic Dance Music (EDM). It would be a mistake to exclude the impact that disco had upon house, techno, acid house, and dance music in general. While disco evolved mostly in the dance capital of America (New York), it proposed the idea that danceable songs could be mixed smoothly together, allowing for long term dancing to previously recorded music. Prior to the disco era, nightlife dancing was restricted to bands or jukeboxes, which limited variety and options of songs and genres. The selections of the DJs mattered more than their technical excellence at mixing. -

Descarga Directa En

DÍAS DE VINILO UNA HISTORIA DEL DISEÑO GRÁFICO MUSICAL 17 de abril - 13 de septiembre de 2015 Salas 1, 3, 4, 5, 6 y 7 EXPOSICIÓN CATÁLOGO Organización y Producción Textos Patio Herreriano, Museo de Arte F. Javier Panera Cuevas Contemporáneo Español. Fotografías Comisario © Archivo Fotográfico Museo Patio F. Javier Panera Cuevas Herreriano (Juan Carlos Quindós) Coordinación Diseño y maquetación Patricia Sánchez Cid María Ángeles Díez Mendoza Comunicación ISBN 978-84-96286-31-3 Susana Gil Trigueros Todos los derechos reservados Montaje © De las imágenes y los textos Feltrero División Arte sus autores © De la edición Museo Patio Seguro Herreriano Aon - AXA Art Selección de obras de la Colección Arte Contemporáneo-Museo Patio Herreriano integradas en DÍAS DE VINILO. Una historia del diseño Serenade (1989) gráfico musical Elena Asins Colección Arte Contemporáneo Bodegón cubista con guitarra (1925) José Moreno Villa Tríptico transformable (1966) CAC Aon Gil y Carvajal, S.A. Manuel Barbadillo CAC Gas Natural Fenosa Bodegón cubista con guitarra (1925) José Moreno Villa Pieza escuchando la pared (1992) CAC ACS, Actividades de Construcción y Juan Muñoz Servicios, S.A. CAC Accenture España, S.L. Couple de danseurs (1926-28) Espacio rítmico en Fa menor (2007) Joaquín Peinado José Antonio Orts CAC Aon Gil y Carvajal, S.A. CAC Banco Popular Español, S.A. Bodegón con violín y partitura (1930 c.) Dancing with the minimalism 3 (1996) Ismael G. de la Serna Elena del Rivero CAC Unión Fenosa Distribución, S.A. CAC Aon Gil y Carvajal, S.A. Càntic del sol (1975) Dancing with the minimalism 2 (1996) Joan Miró Elena del Rivero Colección Arte Contemporáneo CAC Aon Gil y Carvajal, S.A. -

Break the Game: a Practice-Based Study of Breaking

Break the Game: A Practice-based Study of Breaking and Movement Design in Video Games JoDee Allen A Thesis In the Department of Individualized Program (INDI) Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts INDI at Concordia University Montreal, Quebec, Canada August 2015 © JoDee Allen, 2015 ii CONCORDIA UNIVERSITY School of Graduate Studies This is to certify that the thesis prepared By: JoDee Allen Entitled: Break the Game: A Practice-based Study of Breaking and Movement Design in Video Games and submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts – Individualized Program Complies with the regulations of the University and meets the accepted standards with respect to the originality and quality. Signed by the final examining committee: _________________________________ Chair M.J. Thompson _________________________________ Examiner Bart Simon _________________________________ Examiner Sha Xin Wei _________________________________ Supervisor Michael Montanaro Approved by ______________________________________________________________________________ Chair of Department or Graduate Program Director __________________2015 _______________________________________________________________ Dean of Faculty iii ABSTRACT Break the Game: A Practice-based Study of Breaking and Movement Design in Video Games JoDee Allen As players go through a circular pattern of experiencing games they pass through: observation, interpretation, hypothesis making, decision-making then finally acting upon decisions. Their successes and failures help the player construct an understanding of the game world, and as a result increases their confidence in their ability to make informed decisions when faced with game play challenges. In order for a player to be emotionally absorbed by the game’s story they must be fully immersed in the action. -

Occupational Safety and Health Admin., Labor § 1926.604

PART 1926—SAFETY AND HEALTH 1926.61 Retention of DOT markings, plac- ards and labels. REGULATIONS FOR CONSTRUCTION 1926.62 Lead. 1926.64 Process safety management of high- Subpart A—General ly hazardous chemicals. 1926.65 Hazardous waste operations and Sec. emergency response. 1926.1 Purpose and scope. 1926.66 Criteria for design and construction 1926.2 Variances from safety and health of spray booths. standards. 1926.3 Inspections—right of entry. Subpart E—Personal Protective and Life 1926.4 Rules of practice for administrative adjudications for enforcement of safety Saving Equipment and health standards. 1926.95 Criteria for personal protective 1926.5 OMB control numbers under the Pa- equipment. perwork Reduction Act. 1926.96 Occupational foot protection. 1926.6 Incorporation by reference. 1926.97 Electrical protective equipment. 1926.98 [Reserved] Subpart B—General Interpretations 1926.100 Head protection. 1926.10 Scope of subpart. 1926.101 Hearing protection. 1926.11 Coverage under section 103 of the act 1926.102 Eye and face protection. distinguished. 1926.103 Respiratory protection. 1926.12 Reorganization Plan No. 14 of 1950. 1926.104 Safety belts, lifelines, and lanyards. 1926.13 Interpretation of statutory terms. 1926.105 Safety nets. 1926.14 Federal contract for ‘‘mixed’’ types 1926.106 Working over or near water. of performance. 1926.107 Definitions applicable to this sub- 1926.15 Relationship to the Service Contract part. Act; Walsh-Healey Public Contracts Act. 1926.16 Rules of construction. Subpart F—Fire Protection and Prevention 1926.150 Fire protection. Subpart C—General Safety and Health 1926.151 Fire prevention. Provisions 1926.152 Flammable liquids.