Experience of Disability In, Through, and Around Music Through Narrative

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

EDM (Dance Music): Disco, Techno, House, Raves… ANTHRO 106 2018

EDM (Dance Music): Disco, Techno, House, Raves… ANTHRO 106 2018 Rebellion, genre, drugs, freedom, unity, sex, technology, place, community …………………. Disco • Disco marked the dawn of dance-based popular music. • Growing out of the increasingly groove-oriented sound of early '70s and funk, disco emphasized the beat above anything else, even the singer and the song. • Disco was named after discotheques, clubs that played nothing but music for dancing. • Most of the discotheques were gay clubs in New York • The seventies witnessed the flowering of gay clubbing, especially in New York. For the gay community in this decade, clubbing became 'a religion, a release, a way of life'. The camp, glam impulses behind the upsurge in gay clubbing influenced the image of disco in the mid-Seventies so much that it was often perceived as the preserve of three constituencies - blacks, gays and working-class women - all of whom were even less well represented in the upper echelons of rock criticism than they were in society at large. • Before the word disco existed, the phrase discotheque records was used to denote music played in New York private rent or after hours parties like the Loft and Better Days. The records played there were a mixture of funk, soul and European imports. These "proto disco" records are the same kind of records that were played by Kool Herc on the early hip hop scene. - STARS and CLUBS • Larry Levan was the first DJ-star and stands at the crossroads of disco, house and garage. He was the legendary DJ who for more than 10 years held court at the New York night club Paradise Garage. -

Discourse on Disco

Chapter 1: Introduction to the cultural context of electronic dance music The rhythmic structures of dance music arise primarily from the genre’s focus on moving dancers, but they reveal other influences as well. The poumtchak pattern has strong associations with both disco music and various genres of electronic dance music, and these associations affect the pattern’s presence in popular music in general. Its status and musical role there has varied according to the reputation of these genres. In the following introduction I will not present a complete history of related contributors, places, or events but rather examine those developments that shaped prevailing opinions and fields of tension within electronic dance music culture in particular. This culture in turn affects the choices that must be made in dance music production, for example involving the poumtchak pattern. My historical overview extends from the 1970s to the 1990s and covers predominantly the disco era, the Chicago house scene, the acid house/rave era, and the post-rave club-oriented house scene in England.5 The disco era of the 1970s DISCOURSE ON DISCO The image of John Travolta in his disco suit from the 1977 motion picture Saturday Night Fever has become an icon of the disco era and its popularity. Like Blackboard Jungle and Rock Around the Clock two decades earlier, this movie was an important vehicle for the distribution of a new dance music culture to America and the entire Western world, and the impact of its construction of disco was gigantic.6 It became a model for local disco cultures around the world and comprised the core of a common understanding of disco in mainstream popular music culture. -

Winter20 Vol20no1

Winter20 vol20no1 Navigation tools MAGAZINE COVER / BACK PAGE ENLARGE QUADRANT RETURN TO SPREAD VIEW PREVIOUS / NEXT PAGE IN THIS ISSUE CLICK ON PAGE # TO GO TO STORY SCROLL PAGE ( IN ENLARGED VIEW ) WEB LINKS URLS IN TEXT & ADS ALSO CLICKABLE 24 CLICK HERE TO EXIT Get OR USE ctrl/cmd-Q together 30 The faces of small farms Winter20 vol20no1 Features From one ancient event to the relationship of our crops to microbes, a WSU scientist explores the possibilities of symbiosis. 24 Despite the hurdles, a new crop of Washington small farmers are finding their way into the field. 30 UPfront Virtually going where you have never gone before 8 A viral response revisited: The 1918 pandemic at WSC and a modern-day plague journal 10 –11 Inspiring students to dream beyond the limits of cultural stereotypes 14 An orchestra conductor’s concerted effortto give voice to unsung composers 16 Home—whether here or across the Pacific—is in her heart. 17 COVER: SAGEBRUSH COMMUNITY AT SADDLE ROCK IN CHELAN COUNTY (PHOTO AARON THEISEN) LEFT: LICHEN (BIOLOGICAL SYMBIOSIS OF ALGAE, FUNGUS, AND BACTERIA) ON PONDEROSA PINE NEAR LEAVENWORTH (PHOTO GREGG ZIMMERMAN) connecting you to WASHINGTON STATE UNIVERSITY the STATE the WORLD Chasing glacier “mice” in the world’s coldest locations LAST WORDS 52 SCOTT HOTALING (COURTESY KELLEY LAB/WSU SCHOOL OF BIOLOGICAL STUDIES) Departments Thematics 5 Symbiosis FIRST WORDS OUR STORY 12 20 Kyle Smith—guiding a transition game 21 Butch and the A PARTNERSHIP Lest we forget their Butchmen SIDELINES ultimate sacrifice 22 A new apple star comes to market IN SEASON 13 Other degrees BUILT ON 37 The ultimate physical exam 38 Taryn your radio ON of giving after WWII 39 Five questions with Jennifer Adair 40 Building on new directions ALUMNI PROFILES SHORT SUBJECT 18 COMMUNITY 41 40 by ’20 ALUMNI NEWS Big thinking about the 42 Do No Harm, Saving the Oregon Trail NEW MEDIA infinitesimal world of Like WSU, we believe in helping the community. -

Joseph Gallucci Prof. Howard Besser Intro to Moving Image Archiving And

Joseph Gallucci Prof. Howard Besser Intro to Moving Image Archiving and Preservation 9 December 2008 Our Sequined Heritage: A Night at the Gallery and the Audiovisual Record of New York's Underground Dance Clubs In the popular consciousness, at least among those who lived through the era and into the following generation, the word "disco" registers in the mind as something ersatz, plastic, disposable, chintzy, and, as the implication of such labels suggests, ultimately insignificant. A certain set of signifiers are automatically associated with discotheques: John Travolta's character in Saturday Night Fever, suited all in white with gold chains adorning an exposed, hirsute chest; glamorous celebrities engaging in unspeakably decadent behavior; and of course, the omnipresent music that seemingly refuses to die, falsetto male voices (save for Barry White) and belting divas over bouncy, string-laden, and percussive pop songs that are more often than not described as "guilty pleasures" by the very people who sing along to them at karaoke bars or dance to them at weddings. It It is telling that on Wikipedia, disco belongs to the subject category "1970s fads" (its arguable spiritual descendant, new wave, is similarly listed as a "1980s fad"). Punk, on the other hand, which emerged roughly simultaneously with disco's ascendance to the pop culture stratosphere, manages to escape this vaguely derogatory classification, perhaps because it was never embraced to quite the extent that disco was and cannot technically qualify as a "fad." However much these archetypes have persisted, it should be stated that little of it was rooted in reality: Saturday Night Fever, for instance, was based on an article written by Nik Cohn for New York Magazine that, while not too far off from the truth vis-à-vis the Italian-American inner-city working-class preoccupation with disco, was mostly fabricated (Laurino 137). -

7 Pros That Use the Avalon 737

7 Pros that use the Avalon 737 ! August 18, 2015 (http://www.recordingreviews.com/avalon-737/) " Dan (http://www.recordingreviews.com/author/dan/) # Audio (http://www.recordingreviews.com/category/audio/) Start Download File size: 487KB. OS: MacOSX. Rating: 5.0 Stars - Yeti The Avalon 737sp preamp is a staple in the studio, yet is not without controversy. You can regularly find engineers bashing it on forums, or as we have heard one tech call it, “A wire with gain”. We use it in our studio and love it. If you want to hear it in action, you can check out an in-depth Avalon 737 Demo (/avalon-737sp-review/) with audio samples we did some time ago. So, we know what a lot of unknown engineers on the audio forums think. But we set out to find out what the Pros think. So after a full day of research and about 7 pots of coffee, we came up with this list of 7 Pros that use the Avalon 737. Dave Pensado (http://www.pensadosplace.tv/) @pensadosplace CREDITS: MICHAEL JACKSON – EARTH, WIND & FIRE – MARIAH CAREY – P!NK – BEYONCÉ – SHAKIRA – USHER – WILL SMITH Back in 2004, a guest user on Gearslutz (https://www.gearslutz.com/board/q-dave-pensado/20626-dave-what-outboard-do-u-consider- mandatory.html) asked Dave a pretty straightforward question. “Dave what outboard do u consider mandatory?“ See screenshot below: Well that is pretty damn direct! I myself would love to know what gear Dave friggen Pensado considers not only a must have, but mandatory! Thankfully, Dave responded to the post and not only mentioned the Avalon 737, but made sure to put in parenthesis “a great all in one“. -

Disturbed | Primary Wave Music

DISTURBED facebook.com/Disturbed disturbed.lnk.to/instagram twitter.com/disturbed Imageyoutube.com/user/DisturbedTV not found or type unknown disturbed1.com en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Disturbed_(band) open.spotify.com/artist/3TOqt5oJwL9BE2NG9MEwDa Disturbed is an American hard rock band from Chicago, Illinois, formed in 1994. The band includes vocalist David Draiman, bassist John Moyer, guitarist/keyboardist Dan Donegan, and drummer Mike Wengren. Former band members are vocalist Erich Awalt and bassist Steve Kmak. The band has released six studio albums, five of which have consecutively debuted at number one on the Billboard 200. Disturbed went into hiatus in October 2011, during which the band’s members focused on various side projects, and returned in June 2015, releasing their first album in four years, Immortalized, on August 21, 2015. They also recorded and released one live album, Disturbed: Live at Red Rocks on November 18, 2016, which was recorded on August 18, 2016 at Red Rocks Amphitheater in Morrison, Colorado, located about 10 miles west of Denver, Colorado. Their seventh studio album, Evolution, was released on October 19, 2018. Before David Draiman joined Disturbed, guitarist Dan Donegan, drummer Mike Wengren, and bassist Steve “Fuzz” Kmak were in a band called Brawl with vocalist Erich Awalt. Before changing their name to “Brawl”, however, Donegan mentioned in the band’s DVD, Decade of Disturbed, that the name was originally going to be “Crawl”; they switched it to “Brawl”, due to the name already being used by another band. Awalt left the band shortly after the recording of a demo tape; the other three members advertised for a singer. -

The Loft Cinema Film Guide

loftcinema.org THE LOFT CINEMA Showtimes: FILM GUIDE 520-795-7777 JUNE 2019 WWW.LOFTCINEMA.ORG See what films are playing next, buy tickets, look up showtimes & much more! ENJOY BEER & WINE AT THE LOFT CINEMA! We also offer Fresco Pizza*, Tucson Tamale Company Tamales, Burritos from Tumerico, Ethiopian Wraps from JUNE 2019 Cafe Desta and Sandwiches from the 4th Ave. Deli, along with organic popcorn, craft chocolate bars, vegan LOFT MEMBERSHIPS 5 cookies and more! *Pizza served after 5pm daily. SPECIAL ENGAGEMENTS 6-27 SOLAR CINEMA 6, 9, 14, 17, 21 NATIONAL THEATRE LIVE 10 BEER OF THE MONTH: LOFT JR. 11 SUMMERFEST ESSENTIAL CINEMA 13 SIERRA NEVADA BREWING CO. LOFT STAFF SELECTS 19 ONLY $3.50 ALL THROUGH JUNE! COMMUNITY RENTALS 23 REEL READS SELECTION 25 CLOSED CAPTIONS & AUDIO DESCRIPTIONS! THE FILMS OF CHER 26-27 The Loft Cinema offers Closed Captions and Audio NEW FILMS 32-43 Descriptions for films whenever they are available. Check our MONDO MONDAYS 46 website to see which films offer this technology. CULT CLASSICS 47 FILM GUIDES ARE AVAILABLE AT: FREE MEMBERS SCREENING • 1702 Craft Beer & • Epic Cafe • R-Galaxy Pizza BE NATURAL... • Ermanos • Raging Sage (SEE PAGE 37) • aLoft Hotel • Fantasy Comics • Rocco’s Little FRIDAY, JUNE 14 AT 7:00PM • Antigone Books • First American Title Chicago • Aqua Vita • Frominos • SW University of • Black Crown Visual Arts REGULAR ADMISSION PRICES • Heroes & Villains Coffee • Shot in the Dark $9.75 - Adult | $7.25 - Matinee* • Hotel Congress $8.00 - Student, Teacher, Military • Black Rose Tattoo Cafe • Humanities $6.75 - Senior (65+) or Child (12 & under) • Southern AZ AIDS $6.00 - Loft Members • Bookman’s Seminars Foundation *MATINEE: ANY SCREENING BEFORE 4:00PM • Bookstop • Jewish Community • The Historic Y Tickets are available to purchase online at: • Borderlands Center • Time Market loftcinema.org/showtimes Brewery • KXCI or by calling: 520-795-0844 • Tucson Hop Shop • Brooklyn Pizza • La Indita • UA Media Arts Phone & Web orders are subject to a • Cafe Luce • Maynard’s Market $1 surcharge. -

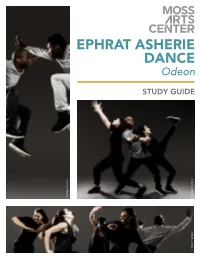

EPHRAT ASHERIE DANCE Odeon

EPHRAT ASHERIE DANCE Odeon STUDY GUIDE ©Matthew Murphy ©Matthew Murphy ©Matthew Murphy Wednesday, March 31, 2021, 10 AM EDT PROGRAM Odeon Choreographer: Ephrat Asherie, in collaboration with Ephrat Asherie Dance Music: Ernesto Nazareth Musical Direction: Ehud Asherie Lighting Design: Kathy Kaufmann Costume Design: Mark Eric We gratefully acknowledge and thank the Joyce Theater’s School & Family Programs for generously allowing the Moss Arts Center’s use and adaptation of its Ephrat Asherie Dance Odeon Resource and Reference Guide. Heather McCartney, director | Rachel Thorne Germond, associate EPHRAT ASHERIE DANCE “Ms. Asherie’s movement phrases—compact bursts of choreography with rapid-fire changes in rhythm and gestural articulation—bubble up and dissipate, quickly paving the way for something new.” –The New York Times THE COMPANY Ephrat Asherie Dance (EAD) is a dance company rooted in Black and Latinx vernacular dance. Dedicated to exploring the inherent complexities of various street and club dances, including breaking, hip-hop, house, and vogue, EAD investigates the expansive narrative qualities of these forms as a means to tell stories, develop innovative imagery, and find new modes of expression. EAD’s first evening-length work,A Single Ride, earned two Bessie nominations in 2013 for Outstanding Emerging Choreographer and Outstanding Sound Design by Marty Beller. The company has presented work at Apollo Theater, Columbia College, Dixon Place, FiraTarrega, Works & Process at the Guggenheim, Jacob’s Pillow Dance Festival, the Joyce Theater, La MaMa, River to River Festival, New York Live Arts, Summerstage, and The Yard, among others. ARTISTIC DIRECTOR Ephrat “Bounce” Asherie is a New York City-based b-girl, performer, choreographer, and director and a 2016 Bessie Award Winner for Innovative Achievement in Dance. -

Aliens, Afropsychedelia and Psyculture

The Vibe of the Exiles: Aliens, Afropsychedelia and Psyculture Feature Article Graham St John Griffith University (Australia) Abstract This article offers detailed comment on thevibe of the exiles, a socio-sonic aesthetic infused with the sensibility of the exile, of compatriotism in expatriation, a characteristic of psychedelic electronica from Goatrance to psytrance and beyond (i.e. psyculture). The commentary focuses on an emancipatory artifice which sees participants in the psyculture continuum adopt the figure of the alien in transpersonal and utopian projects. Decaled with the cosmic liminality of space exploration, alien encounter and abduction repurposed from science fiction, psychedelic event-culture cultivates posthumanist pretentions resembling Afrofuturist sensibilities that are identified with, appropriated and reassembled by participants. Offering a range of examples, among them Israeli psychedelic artists bent on entering another world, the article explores the interface of psyculture and Afrofuturism. Sharing a theme central to cosmic jazz, funk, rock, dub, electro, hip-hop and techno, from the earliest productions, Israeli and otherwise, Goatrance, assumed an off-world trajectory, and a concomitant celebration of difference, a potent otherness signified by the alien encounter, where contact and abduction become driving narratives for increasingly popular social aesthetics. Exploring the different orbits from which mystics and ecstatics transmit visions of another world, the article, then, focuses on the socio- sonic aesthetics of the dance floor, that orgiastic domain in which a multitude of “freedoms” are performed, mutant utopias propagated, and alien identities danced into being. Keywords: alien-ation; psyculture; Afrofuturism; posthumanism; psytrance; exiles; aliens; vibe Graham St John is a cultural anthropologist and researcher of electronic dance music cultures and festivals. -

Disturbed the Sickness Album Download Rar Disturbed the Sickness Album Download Rar

disturbed the sickness album download rar Disturbed the sickness album download rar. Completing the CAPTCHA proves you are a human and gives you temporary access to the web property. What can I do to prevent this in the future? If you are on a personal connection, like at home, you can run an anti-virus scan on your device to make sure it is not infected with malware. If you are at an office or shared network, you can ask the network administrator to run a scan across the network looking for misconfigured or infected devices. Another way to prevent getting this page in the future is to use Privacy Pass. You may need to download version 2.0 now from the Chrome Web Store. Cloudflare Ray ID: 67b17cbe28604e80 • Your IP : 188.246.226.140 • Performance & security by Cloudflare. Disturbed the sickness album download rar. DISTURBED. Disturbed merupakan sebuah grup musik metal Amerika Serikat yang didirikan pada tahun 1996. Anggotanya berjumlah 4 orang, yaitu David Draiman , Dan Donegan, John Moyer , dan Mike Wengren . Sejak band ini diluncurkan, album mereka telah terjual sebanyak 11 juta kopi di seluruh dunia. Menjadikan mereka sebagai salah satu band heavy metal tersukses abad ini. CARA DOWNLOAD KLIK TULISAN YANG BERGARIS MIRING. Ini recomendasi lagu Disturbed Paling Bagus Menurut saya dan wajib punya. Daftar Lagu : 01. Hell (from Ten Thousand Fists) 02. A Welcome Burden (from The Sickness) 03. This Moment (from Transformers: The Album) 04. Old Friend (from Asylum) 05. Monster (from Ten Thousand Fists) 06. Run (from Indestructible) 07. Leave It Alone (from Asylum) 08. -

New York State Multiple Dwelling Law Article 1 Introductory Provisions; Definitions

NEW YORK STATE MULTIPLE DWELLING LAW ARTICLE 1 INTRODUCTORY PROVISIONS; DEFINITIONS §1. Short title. This chapter shall be known as the "multiple dwelling law." §2. Legislative finding. It is hereby declared that intensive occupation of multiple dwelling sites, overcrowding of multiple dwelling rooms, inadequate provision for light and air, and insufficient protection against the defective provision for escape from fire, and improper sanitation of multiple dwellings in certain areas of the state are a menace to the health, safety, morals, welfare, and reasonable comfort of the citizens of the state; and that the establishment and maintenance of proper housing standards requiring sufficient light, air, sanitation and protection from fire hazards are essential to the public welfare. Therefore the provisions hereinafter prescribed are enacted and their necessity in the public interest is hereby declared as a matter of legislative determination. §3. Application to cities, towns and villages. 1. This chapter shall apply to all cities with a population of three hundred twenty-five thousand or more. 2. The legislative body of any other city, town or village may adopt the provisions of this chapter and make the same applicable to dwellings within the limits of such city, town or village by the passage of a local law or ordinance adopting the same; and upon the passage of such local law or ordinance all of the provisions of articles one, two, three, four, five, ten and eleven and such sections or parts of sections of the other articles of this chapter as such local law or ordinance shall enumerate, shall apply to such city, town or village from the date stated in such law or ordinance. -

Love Saves the Day

LOVE SAVES THE DAY DAVID MANCUSO AND THE LOFT BY TIM LAWRENCE 002 Like a soup or a bicycle or Wikipedia, the Loft is an amal- ophy around the psychedelic experience that would in- 003 gamation of parts that are weak in isolation, but joyful, rev- form the way records were selected at the Loft, was anoth- elatory and powerful when joined together. The first in- er echo that resonated at the Broadway Loft. Co-existing gredient is the desire of a group of friends to want to get with Leary, the civil rights, the gay liberation, feminist and together and have some fun. The second element is the the anti-war movements of the 1960s were manifest in discovery of a room that has good acoustics and is comfort- the egalitarian, rainbow coalition, come-as-you-are ethos able for dancing, which means it should have rectangular of the Loft. And the Harlem rent parties of the 1920s, in dimensions, a reasonably high ceiling, a nice wooden floor which economically underprivileged African American and the possibility of privacy. The next building block is tenants put on shindigs in order to help raise some money the sound system, which is most effective when it is sim- (through "donations" made at the door) to pay the rent, ple, clean and warm, and when it isn't pushed more than a established a template for putting on a private party that fraction above 100 decibels (so that people's ears don't be- didn't require a liquor or cabaret license and could ac- come tired or even damaged).