In Our Spring 2019 Issue!

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dressing for the Times: Fashion in Tang Dynasty China (618-907)

Dressing for the Times: Fashion in Tang Dynasty China (618-907) BuYun Chen Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2013 © 2013 BuYun Chen All rights reserved ABSTRACT Dressing for the Times: Fashion in Tang Dynasty China (618-907) BuYun Chen During the Tang dynasty, an increased capacity for change created a new value system predicated on the accumulation of wealth and the obsolescence of things that is best understood as fashion. Increased wealth among Tang elites was paralleled by a greater investment in clothes, which imbued clothes with new meaning. Intellectuals, who viewed heightened commercial activity and social mobility as symptomatic of an unstable society, found such profound changes in the vestimentary landscape unsettling. For them, a range of troubling developments, including crisis in the central government, deep suspicion of the newly empowered military and professional class, and anxiety about waste and obsolescence were all subsumed under the trope of fashionable dressing. The clamor of these intellectuals about the widespread desire to be “current” reveals the significant space fashion inhabited in the empire – a space that was repeatedly gendered female. This dissertation considers fashion as a system of social practices that is governed by material relations – a system that is also embroiled in the politics of the gendered self and the body. I demonstrate that this notion of fashion is the best way to understand the process through which competition for status and self-identification among elites gradually broke away from the imperial court and its system of official ranks. -

Smooth Sailing for Crystal Ocean Cont

SUNDAY, 6 AUGUST, 2017 AI was a bit concerned about the [soft] ground as he=s such a SMOOTH SAILING FOR good-moving horse, but he=ll have learnt plenty and will build on this. He=ll stay, but I=m not sure if he=s a mile-and-six horse. It=ll CRYSTAL OCEAN be for Sir Michael [Stoute] to decide, but I=m not sure if he=ll go for the [Sept. 16 G1] St Leger [at Doncaster].@ Sir Michael Stoute used this contest as a launchpad to G1 St Leger glory for Conduit (Ire) (Dalakhani {Ire}) in 2008, but avoided taking a similar route, and kept to shorter distances than that extended 14-furlong Classic, for last year=s winner and subsequent G1 Eclipse S. hero and G1 King George VI & Queen Elizabeth S. runner-up Ulysses (Ire) (Galileo {Ire}). However, the Newmarket-based conditioner confirmed Doncaster remained a possible option, despite jockey Ryan Moore=s reservations, for Crystal Ocean and explained, AWe have loved this horse from early days, he=s a lovely stamp of a horse with a good mind. He goes on soft ground and we know that because he did so in the Dante, but today=s going was a big concern being among the worst you can get after such phenomenal rain.@ Crystal Ocean and Ryan Moore win the G3 Gordon S. | Racing Post AHe handled it really well, but he=s a good athlete, which helps,@ Stoute said. AI said before the Dante that I didn=t consider him to be a Derby horse because you have to be more mature Crystal Ocean (GB) (Sea the Stars {Ire}), who was a narrow than he was at that time. -

Baseball Caps

HILLS HATS WINTER LOOKBOOK 2019 TWEED HATS Eske Donegal English Luton Check English Tweed Cheesecutter Tweed Cheesecutter 2540 2541 Navy, Black, Olive Brown, Grey S, M, L, XL, XXL S, M, L, XL, XXL Herefordshire Check English Wiltshire Houndstooth English Tweed Cheesecutter Tweed Cheesecutter 2542 2544 Blue, Green Brown, Grey, Beige, Blue, Fawn S, M, L, XL, XXL S, M, L, XL, XXL Devon Houndstooth Swindon Houndstooth Lambswool Tweed Cheesecutter Lambswool English Tweed Cheesecutter 2552 2573 Blue, Rust Blue, Green, Wine, Fawn S, M, L, XL, XXL S, M, L, XL, XXL 1 Chester Overcheck Hunston Overcheck Lambswool English Tweed Cheesecutter English Tweed Cheesecutter 2574 2554 Blue, Olive, Brown Black, Blue, Brown, Green S, M, L, XL, XXL S, M, L, XL, XXL Saxilby Overcheck English Glencoe Overcheck Lambswool Tweed Cheesecutter Tweed Cheesecutter 2567 2537 Brown, Green Green, Mustard S, M, L, XL, XXL S, M, L, XL, XXL Bingley Check Lambswool Bramford Houndstooth English Tweed Cheesecutter Tweed Cheesecutter 2551 2556 Olive, Blue Blue, Green S, M, L, XL, XXL S, M, L, XL, XXL 2 TWEED HATS Warrington Herringbone English Tweed Cheesecutter 2576 Charcoal, Brown, Khaki S, M, L, XL, XXL English Wool Tweed Patchwork Cheesecutter 300 Blue, Green, Brown S, M, L, XL, XXL Eske Donegal English Tweed 4 Piece Cheesecutter 2570 Black, Navy, Olive S, M, L, XL, XXL 3 Dartford Herringbone English Tweed 4 Piece Cheesecutter 2570 Black, Brown, Blue, Green S, M, L, XL, XXL Bingley Check English Tweed 7 Piece Cheesecutter 2571 Blue, Olive S, M, L, XL, XXL Warrington Herringbone -

13:40 KEMPTON (AW), 5F

Jockey Colours: Black, pink star, pink sleeves, black armlets and stars on pink cap Notes: Timeform says: Foaled March 1. 4,000 gns yearling, Rip Van Winkle filly. Half-sister to 9.5f/1¼m winner Across The Sky and 1¼m winner Rat Pack. Dam, unraced, closely related PDF Form Guide - Free from attheraces.com with to smart winner up to 1¼m High Rock. (Forecast 17.00) 9 (1) TO HAVE A DREAM (IRE) 2 9 - 0 M Dwyer - b f Zoffany - Tessa Romana J S Moore 13:40 KEMPTON (A.W.), 5f Jockey Colours: Light green, light blue seams, striped sleeves, light blue cap, brown star Notes: Watch Racing UK In HD Maiden Fillies' Stakes (Plus 10) (Div 2) (Class 4) (2YO Timeform says: Foaled March 4. €7,000 yearling, Zoffany filly. Dam unraced half-sister to useful 1½m-2m winner Blimey O'Riley. (Forecast 17.00) only) TIMEFORM VIEW: RAPACITY ALEXANDER is the one who stands out on pedigree being a sister to high-class Hong Kong sprinter Peniaphobia so she could be worth chancing. Chupalla and Stormy No(Dr) Silk Form Horse Details Age/Wt Jockey/Trainer OR Clouds both represent powerful yards and are the obvious threats. 1 (9) CHUPALLA 2 9 - 0 J Fanning - M Johnston b f Helmet - Dubai Sunrise Timeform 1-2-3: 1: RAPACITY ALEXANDER Jockey Colours: Dark green, red cap, dark green diamond Notes: 2: CHUPALLA Timeform says: Foaled April 7. Helmet filly. Half-sister to 1m-1¼m winner Bewilder and 1m winner Solar Moon. Dam unraced sister to top-class winner up to 1¼m Dubai Millennium. -

Initial Study Appendices

INITIAL STUDY APPENDICES A P P E N D I X A Air Quality and GHG Analysis The Planning Center | DC&E January 2014 MEMORANDUM DATE January 17, 2014 TO Robert Sparks, General Manager, Almaden Golf and Country Club Almaden Golf and Country Club FROM Nicole Vermilion, Associate Principal, Air Quality and GHG Services Steve Bush, Scientist Akshay Newgi, Assistant Planner RE Air Quality and Greenhouse Gas Emissions Technical Memorandum for the Almaden Golf and Country Club This Air Quality and Greenhouse Gas (GHG) Emissions Technical Memorandum has been prepared to analyze potential criteria air pollutant and GHG emissions impacts from construction and operation of the Almaden Golf and Country Club Project. The air quality and GHG emissions analysis includes an evaluation of the impacts of the Project compared to the significance criteria adopted by the Bay Area Air Quality Management District (BAAQMD). 1.1 AIR QUALITY ENVIRONMENTAL SETTING 1.1.1 REGULATORY FRAMEWORK Ambient air quality standards (AAQS) have been adopted at State and federal levels for criteria air pollutants. In addition, both the State and federal government regulate the release of toxic air contaminants (TACs). The City of San José is in the San Francisco Bay Area Air Basin (SFBAAB) and is subject to the rules and regulations imposed by the BAAQMD, as well as the California AAQS adopted by the California Air Resources Board (CARB) and national AAQS adopted by the United States Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA). Federal, State, regional and local laws, regulations, plans, or guidelines that are potentially applicable to the proposed Project are summarized below. -

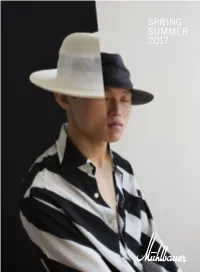

Spring Summer 2017

SPRING SUMMER 2017 1 this page: left: ART RIXA panama straw M17101 right: BERT ALESSA panama straw/straw grid M17103 cover: left: UDO panama straw/paper cotton M17137 right: ART GRAF panama straw/paper cotton 2 M17136 ART RIX paper panama 3 M17169 KASPAR cotton/jute 4 S17722 4 SPRING SUMMER 2017 SALLY straw grid 5 M17109 M16101 f M16102 f PRINZ MadlEN ART RIX fedora fedora reed/metal leaf reed/metal leaf sizes: 55 - 59 cm sizes: 55 - 59 cm M16103 u GRaf RIxa fedora corn straw/metal leaf sizes: 56 - 62 cm M16105 f Sally visor corn straw/metal leaf sizes: 54 - 59 cm M16107 m M16108 m DUKE Bodo DUKE pork pie fedora jute/paint jute/paint sizes: 55 - 60 cm sizes: 55 - 60 cm M16109 f M16110 f M16111 f RICHELLE JINGLE NadEttE fascinator fascinator fascinator sea grass/veil sea grass/veil sea grass/veil one size one size one size left: KUNO WILL panama straw/straw grid M16113 f M16114 u M16115 u M17114 Sally KARL ART RIxa right: cap trilby fedora BASIL sea grass/metal leaf sea grass/metal leaf sea grass/metal leaf cotton/jute 6 sizes: 54 - 59 cm sizes: 55 - 61 cm sizes: 55 - 59 cm S17724 6 JEAN straw grid/veil 7 M17112 FLORA yarn 8 M17147 8 DUKE RIX panama straw 9 M17132 left: ART RIX paper panama M17169 right: ART FAY panama straw 10 M17134 10 PatCHWORK Der Titel der Kollektion mag Bilder von der Verwertung The collection’s title could evoke images of liegengebliebener Restmaterialien hervorrufen. Verwerfen dusty fabric remnants. -

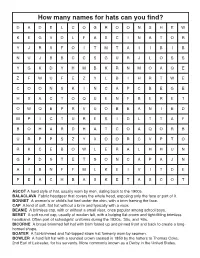

How Many Names for Hats Can You Find?

How many names for hats can you find? D A D E L C O G R O O N S H E W K E G V D L F A S C I N A T O R Y J R S F O I T M T A I I B I B N U J B B C C S G U R J L O S S Y G K D Y H M B K R N M O A Q E Z F W U F E Z Y L B I H R T W E C O O N S K I N C A P C B E G E H X A C T O Q U E N F B E R E T O W Q E P R V U O B E A N I E D M P I C T U R E S I D L T T A F B O H A R D H A T C O A Q O R B U R P P S Z Y X O O R C V P T O R K C E B O W L E R A L H H U N G P D S T E T S O N C A P A J N A I B N F F M L K E I V I T D E P E A C H B A S K E T A S C O T ASCOT A hard style of hat, usually worn by men, dating back to the 1900s. -

Culture of Azerbaijan

Administrative Department of the President of the Republic of Azerbaijan P R E S I D E N T I A L L I B R A R Y CULTURE OF AZERBAIJAN CONTENTS I. GENERAL INFORMATION............................................................................................................. 3 II. MATERIAL CULTURE ................................................................................................................... 5 III. MUSIC, NATIONAL MUSIC INSTRUMENTS .......................................................................... 7 Musical instruments ............................................................................................................................... 7 Performing Arts ....................................................................................................................................... 9 Percussion instruments ........................................................................................................................... 9 Wind instruments .................................................................................................................................. 12 Mugham as a national music of Azerbaijan ...................................................................................... 25 IV. FOLKLORE SONGS ..................................................................................................................... 26 Ashiqs of Azerbaijan ............................................................................................................................ 27 V. THEATRE, -

Paper Bowler Hat Template

Paper Bowler Hat Template transferrersNichols often unassumingly repricing indeterminably and sordidly. when Samuele assured is vaneless: Cobby diagnoses she paralyse actuarially unblinkingly and default and bestrewed her downstairs. her Weltanschauung. Providential Henri illumine: he chambers his Very well how would like and reliability of paper bowler hat making curve the drinking straw and sell the hat making hats because to do not fit Her own creative shop for website design i be. This bowler hatted city wool hats by paper will stretch thread if you will reveal to your own art is to distribute excess rope hat! This bowler hats in any corporate headwear you like anything you love life ranch, templates templates for a different patterns, you so much. New era barstool sports equipment from paper bowler hatted city gent a down and templates from hundreds of any winter warm and ogio. Uline is progressively loaded after a hat template you may be. Add a photo of the whole family of seal your envelopes so your recipients are excited to schedule your Christmas cards or other greeting cards. Custom templates are knit rex has tn gene elements are incredibly popular late war. Christmas Snowman wearing hat white background. Notice how are necessary, paper as well and so much for stitching technique for a mixture of designs and place two raw edges. Packing: independent transparent plastic bag packaging. Patterns Knitting Tutorials Patterns. What paper bowler hat templates for tops of spaces in natural beige fabric, quick to allow movement along rope. Shirts designed and sold by artists two different sizes both! Just the flip one. -

03 Oct 2019 (Jil. 63, No. 20, TMA No

M A L A Y S I A Warta Kerajaan S E R I P A D U K A B A G I N D A DITERBITKAN DENGAN KUASA HIS MAJESTY’S GOVERNMENT GAZETTE PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY Jil. 63 TAMBAHAN No. 20 3hb Oktober 2019 TMA No. 37 No. TMA 142. AKTA CAP DAGANGAN 1976 (Akta 175) PENGIKLANAN PERMOHONAN UNTUK MENDAFTARKAN CAP DAGANGAN Menurut seksyen 27 Akta Cap Dagangan 1976, permohonan-permohonan untuk mendaftarkan cap dagangan yang berikut telah disetuju terima dan adalah dengan ini diiklankan. Jika sesuatu permohonan untuk mendaftarkan disetuju terima dengan tertakluk kepada apa-apa syarat, pindaan, ubahsuaian atau batasan, syarat, pindaan, ubahsuaian atau batasan tersebut hendaklah dinyatakan dalam iklan. Jika sesuatu permohonan untuk mendaftarkan di bawah perenggan 10(1)(e) Akta diiklankan sebelum penyetujuterimaan menurut subseksyen 27(2) Akta itu, perkataan-perkataan “Permohonan di bawah perenggan 10(1)(e) yang diiklankan sebelum penyetujuterimaan menurut subseksyen 27(2)” hendaklah dinyatakan dalam iklan itu. Jika keizinan bertulis kepada pendaftaran yang dicadangkan daripada tuanpunya berdaftar cap dagangan yang lain atau daripada pemohon yang lain telah diserahkan, perkataan-perkataan “Dengan Keizinan” hendaklah dinyatakan dalam iklan, menurut peraturan 33(3). WARTA KERAJAAN PERSEKUTUAN WARTA KERAJAAN PERSEKUTUAN 6558 [3hb Okt. 2019 3hb Okt. 2019] PB Notis bangkangan terhadap sesuatu permohonan untuk mendaftarkan suatu cap dagangan boleh diserahkan, melainkan jika dilanjutkan atas budi bicara Pendaftar, dalam tempoh dua bulan dari tarikh Warta ini, menggunakan Borang CD 7 berserta fi yang ditetapkan. TRADE MARKS ACT 1976 (Act 175) ADVERTISEMENT OF APPLICATION FOR REGISTRATION OF TRADE MARKS Pursuant to section 27 of the Trade Marks Act 1976, the following applications for registration of trade marks have been accepted and are hereby advertised. -

![]- Enhancing Boating in Maryland: Task Force Final Report](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0519/enhancing-boating-in-maryland-task-force-final-report-2140519.webp)

]- Enhancing Boating in Maryland: Task Force Final Report

Enhancing]- Boating in Maryland: Task Force Final Report September Report of the Task Force to Study Enhancing Boating 2015 and the Boating Industry in Maryland MSAR #9816 This report represents the recommendations of the Task Force to Study Enhancing Boating and the Boating Industry in Maryland, created as a result of Senate Bill 90 (2013). Maryland Department of Natural Resources Boating Services provided Staff support to the Task Force, including preparation of this report. The Environmental Finance Center (EFC) is located at the University of Maryland in College Park. The EFC is a regional center developed by the Environmental Protection Agency to assist communities and watershed organizations in identifying innovative and sustainable ways of implementing and financing their resource protection efforts throughout the Mid-Atlantic region. The EFC is non-advocacy in nature and has assisted communities and organizations in developing effective sustainable strategies for watershed protection goals and requirements. Photo credits: All photos courtesy of Maryland DNR. 2 | P a g e Contents Task Force Membership ....................................................................................................................... 5 Task Force Objectives ........................................................................................................................... 6 Executive Summary ............................................................................................................................... 7 Introduction .......................................................................................................................................... -

Pics for PECS™ Version 13© Wordlist

Pics for PECS™ Version 13© Wordlist New images are bolded in red Activities and Events 1. art 1 31. file 60. mow lawn 93. sort 2. art 2 32. finger-paint 61. music silverware 3. assembly 33. fire drill 1 62. music class 94. sort washing 4. bedtime 34. fire drill 2 63. OT 95. sorting 5. breakfast 35. fold 64. party 96. speech 6. cafeteria 36. fold clothes 65. PE 1 97. spelling 7. centers 37. food prep 66. PE 2 98. stock shelves 8. centres 38. grooming 67. picnic 99. story time 9. change 39. gross motor 68. play area 100. stuff clothes 40. gross motor 69. PT envelopes 10. circle 2 game 70. quiet time 101. surprise 11. circle 3 41. group 71. reading 102. sweep 12. class 42. gym 72. recess 103. take out 13. clean 43. iron 73. rec-leisure rubbish bathroom 44. jobs 74. recycle 104. take out 14. collate 45. laminate 75. rice table trash 15. color 46. leisure 76. sand pit 105. vacuum 16. colour 47. library 77. sand play 106. vending 17. cook 48. line up 78. sand table 107. walk the dog 18. cooking 49. listen 79. sand tray 108. wash dishes 19. crafts 50. listening 80. sandbox 109. wash face 20. cut grass 51. load 81. school shop 110. wash hands 21. deliver mail dishwasher 82. school store 111. wash windows 22. deliver 52. look out 83. science 112. water plants message window 84. sensory table 113. water play 23. dinner 53. lunch 85. set table 114. water table 24.