The Office of Corpus Christi

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

I. History of the Feast of Corpus Christi II. Theology of the Real Presence III

8 THE BEACON § JUNE 11, 2009 PASTORAL LETTER [email protected] [email protected] PASTORAL LETTER THE BEACON § JUNE 11, 2009 9 The Real Presence: Life for the New Evangelization To the priests, deacons, religious and [6] From the earliest times, the Eucharist III. Practical Reflections all the faithful: held a special place in the life of the Church. St. Ignatius, who, as a boy, had heard St. John [9] This faith in the Real Presence moves N the Solemnity of the Most preach and knew St. Polycarp, a disciple of St. us to a certain awe and reverence when we Holy Body and Blood of Christ, John, said, “I have no taste for the food that come to church. We do not gather as at a civic I wish to offer you some perishes nor for the pleasures of this life. I assembly or social event. We are coming into theological, historical and want the Bread of God which is the Flesh of the Presence of our Lord God and Savior. The O practical reflections on the Christ… and for drink I desire His Blood silence, the choice of the proper attire (i.e. not Eucharist. The Eucharist is which is love that cannot be destroyed” (Letter wearing clothes suited for the gym, for sports, “the culmination of the spiritual life and the goal to the Romans, 7). Two centuries later, St. for the beach and not wearing clothes of an of all the sacraments” (Summa Theol., III, q. 66, Ephrem the Syrian taught that even crumbs abbreviated style), even the putting aside of a. -

The Notre Dame Scholastic

Notre Dame ^cholasHc ^iscz'-Q^Q^i^Szmp(^-Victuvx\e'''VxvZ' Quasi- Cray- MoriJuru^ A Literary — News Weekly MARCH 4, 1927 No. 20 1872-1927 < Philosophy Number en o en o -v=^-<^-«i-5'-:Vj,.~^-=;,:.-.—-A-- THE NOTRE DAME SCHOLASTIC WELL DRESSED MEN PREFER MAX ADLER CLOTHES Hickey-Frcemin OMtonuMd Ootbct The LONDON A two-button young men's style, tailored by Hickey- Freeman—and that means it reflects a needled skill as fine as the best custom tailors can achieve—at a price at which they can't afford to do it. For the London costs little more than you would ex pect to pay for a good ready-made suit that wouldn't boast half the custom-made characteristics of Hickey- Freeman clothes. New Spring Topcoats MAX ADLER COM P A N Y ON THE CORNER MICHIGAN AND WASHINGTON THE NOTRE DAME SCHOLASTIC 609 ,ow/ GIFTS IT'S A GIFTS LtAPBURV GIFTS Hate to go gift shopping? You wouldn't if you shopped at. Wyman's. Toys for young relatives in Toyland. Home gifts GET THAT (wedding presents) on the third floor. Mother, Sister and Best Girl birthday - SPRING SUIT gifts all over the store—and dozens of New patterns, new shades in obliging salespeople to help you. stripes, plaids, Scotch weaves, Oxford grays. Come and See Us This stuff is collegiate—well- GEORGE WYMAN made, moderately priced. & COMPANY You'll see Spring Learburys on sJ the campus every day now— lots of them. Come in Mon LOOK WELL— day for yours. AND SUCCEED LEARBURY HE OLIVER HOTEL Authentic-Styled BARBER SHOP : : : : COLLEGE CLOTHES T CATERING TO N. -

Divine Worship Newsletter

ARCHDIOCESE OF PORTLAND IN OREGON Divine Worship Newsletter The Presentation - Pugin’s Windows, Bolton Priory ISSUE 5 - FEBRUARY 2018 Introduction Welcome to the fifth Monthly Newsletter of the Office of Divine Worship of the Archdiocese of Portland in Oregon. We hope to provide news with regard to liturgical topics and events of interest to those in the Archdiocese who have a pastoral role that involves the Sacred Liturgy. The hope is that the priests of the Archdiocese will take a glance at this newsletter and share it with those in their parishes that are interested in the Sacred Liturgy. This Newsletter will be eventually available as an iBook through iTunes but for now it will be available in pdf format on the Archdiocesan website. It will also be included in the weekly priests’ mailing. If you would like to be emailed a copy of this newsletter as soon as it is published please send your email address to Anne Marie Van Dyke at [email protected] just put DWNL in the subject field and we will add you to the mailing list. In this issue we continue a new regular feature which will be an article from the Office of Liturgical Celebrations of His Holiness. Under the guidance of Msgr. Guido Marini, the Holy Father’s Master of Ceremonies, this office has commissioned certain studies of interest to Liturgists and Clergy. Each month we will publish an article or an extract which will be of interest to our readers. If you have a topic that you would like to see explained or addressed in this newsletter please feel free to email this office and we will try to answer your questions and treat topics that interest you and perhaps others who are concerned with Sacred Liturgy in the Archdiocese. -

Ex. Sol. of Corpus Christi 6.23.19.Pub

Institute of Christ the King Sovereign Priest Saint Anthony of Padua Oratory Latin Mass Apostolate in the Archdiocese of Newark Extraordinary Form of the Roman Rite Website: www.institute-christ- king.org/westorange-home Address: Email: 1360 Pleasant Valley Way saint.anthonys@institute- West Orange, N.J. 07052 christ-king.org Phone: Stay Connected to the Institute 973-325-2233 Text "Institute" to 84576 Fax: Receive news, event notifica- tions, Spiritual reflections & 973-325-3081 more via email or text. External Solemnity of Corpus Christi June 23, 2019 JUNE: MONTH OF THE SACRED HEART Holy Mass Schedule: Baptism: Please contact the Oratory in advance. Sunday: 7:30AM, 9:00AM & 11:00AM (High Mass) Marriage: Please contact the Rectory in advance of pro- Weekdays: Monday - Saturday 9:00AM posed marriage date. except Tuesday 7:00PM Benediction of the Most Blessed Sacrament: 2nd Sunday First Friday : Additional Mass at 7:00PM followed of the month following the 9:00AM Holy Mass by Benediction of the Blessed Sacrament Holy Hour of Adoration: Thurs. 7:00PM Holy Days of Obligation: 9:00AM & 7:00PM (Please confirm with current bulletin or website) Novenas after Holy Mass Tuesday: St. Anthony 25th of the month (Infant of Prague): 7:00PM Mass followed by devotions (not on Sat. or Sun.) Wednesday: St. Joseph Confession: Saturday: Our Lady of the Miraculous Medal Monthly from the 17th to 25th: Infant of Prague 30 minutes before each Mass & upon request. Please reference the weekly bulletins (also available on the website) for any temporary changes to the Mass schedule. Very Rev. Msgr. -

Feast of Corpus Christi June 6, 2021

FEAST OF CORPUS CHRISTI JUNE 6, 2021 MASS INTENTIONS Sat. 6/5 4:00 PM Peter and Mayme Sefing by the Turri Family Sun. 6/6 11:00 AM Anna and Andy Prokopovich by Michalene and Jim Eisenhart Mon. 6/7 7:00 PM Helen E. Capozzelli by Bob and Lorraine Giulani Tue. 6/8 7:00 AM Mary Woods by Her Son Jim Mellon Wed 6/9 7:00 AM Nancy Hartzel by Sally and Les Thur. 6/10 7:00 AM Thomas Chuckra, Jr. by His Wife Mary Fran Fri. 6/11 7:00 AM Betty Wysocki by JoAnn Heller Sat. 6/12 4:00 PM Deceased Members of Freeland Class of 1966 by Paula Sun. 6/13 11:00AM James P. Cosgrove, Sr. by His Family Weekend of May 15/16: Sunday $3,930.00; Loose $33.00; Dues $2,051.00; Care and Education of Priests $98.00; Initial Offering $10.00; Solemnity of Mary $10.00; Ash Wednesday $5.00; Holy Thursday $5.00; Good Friday $5.00; Easter Flowers $15.00; Easter $40.00; Ascension $378.00; Holy Father $10.00; Home Mission $21.00; Catholic Communications $206.00; Poor Box $86.00 Weekend of May 22/23: Sunday $3,814.00; Loose $307.00; Dues $946.00; Care and Education of Priests $105.00; Feast of the Assumption $5.00; Christmas $5.00; Rice Bowl $5.00; Easter Flowers $20.00; Holy Thursday $5.00; Good Friday $5.00; Easter $20.00; Catholic Home Mission $20.00; Ascension $46.00; Catholic Communications $80.00; Holy Father $10.00; Poor Box $246.57 Weekend of May 29/30: Sunday $2,767.00; Loose $28.00; Dues $836.00; Care and Education of Priests $40.00; Ascension $45.00; Catholic Communications $25.00; Churches in Europe $20.00; Holy Father $10.00; Poor Box $107.17 CANDLES ON THE ALTAR are in Memory of Walter Tamposki by Dan Ravina MEMORIAL DONATIONS in Memory of Joan Staruch: $50.00 by Debbie, Jessica, and Matthew Stivers; $100.00 by Gerald and Mary Feissner and Family. -

Sacramental Signification: Eucharistic Poetics from Chaucer to Milton

Sacramental Signification: Eucharistic Poetics from Chaucer to Milton Shaun Ross Department of English McGill University, Montreal August 2016 A thesis submitted to McGill University in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy © Shaun Ross 2016 i Table of Contents Abstract……………………………………………………………………………………………ii Resumé……………………………………………………………………………………………iv Acknowledgements…………………………………………………………………………….....vi Introduction………………………………………………………………………………………..1 Chapter One: Medieval Sacraments: Immanence and Transcendence in The Pearl-poet and Chaucer………...23 Chapter Two: Southwell’s Mass: Sacrament and Self…………………………………………………………..76 Chapter Three: Herbert’s Eucharist: Giving More……………………………………………………………...123 Chapter Four: Donne’s Communions………………………………………………………………………….181 Chapter Five: Communion in Two Kinds: Milton’s Bread and Crashaw’s Wine……………………………. 252 Epilogue: The Future of Presence…………………………………………………………………………325 Works Cited…………………………………………………………………………………….330 ii Abstract This dissertation argues that in early modern England the primary theoretical models by which poets understood how language means what it means were applications of eucharistic theology. The logic of this thesis is twofold, based firstly on the cultural centrality of the theology and practice of the eucharist in early modern England, and secondly on the particular engagement of poets within that social and intellectual context. My study applies this conceptual relationship, what I call “eucharistic poetics,” to English religious and -

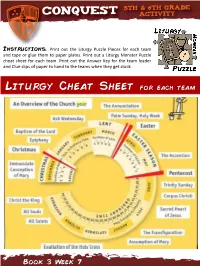

Liturgy Cheat Sheet for Each Team

Instructions: Print out the Liturgy Puzzle Pieces for each team and tape or glue them to paper plates. Print out a Liturgy Monster Puzzle cheat sheet for each team. Print out the Answer Key for the team leader and Clue slips of paper to hand to the teams when they get stuck. Liturgy Cheat Sheet for each team Book 3 Week 7 Answer Key for team leader 1. Advent Season 2. Immaculate Conception 3. Christmas 4. Christmas Season 5. Holy Family 6. Mary, Mother of God 7. Epiphany 8. Baptism of the Lord 9. Ordinary Time after Christmas 10.Ash Wednesday 11. Lent 12.Annunciation 13. Palm Sunday 14. Holy Thursday 15. Good Friday 16. Holy Saturday (Easter Vigil) 17. Easter Sunday 18. Easter Season 19. Ascension 20.Pentecost 21.Ordinary Time after Easter 22.Trinity Sunday 23.Corpus Christi 24.Sacred Heart 25.Immaculate Heart 26.Assumption 27.Triumph of the Cross 28.All Saints Day 29.All Souls Day 30.Christ the King Liturgy clues for team leader to hand out Advent Season The Advent Season is the beginning of the Church's liturgical year. The First Sunday of Advent begins four Sundays before Christmas. Immaculate Conception Each year on December 8th, the Church celebrates this feast which honors the fact that Mary was conceived without original sin through the grace of God so that she may be a fitting home for our savior. Christmas Each year on December 25th, the Church celebrates the birth of our Lord Jesus Christ in history. Christmas Season The Christmas Season runs from Christmas day to the Feast of the Baptism of the Lord. -

1 HOMILY CORPUS CHRISTI YRC 2016 Today Is the Feast of Corpus

HOMILY CORPUS CHRISTI YRC 2016 Today is the feast of Corpus Christi, the Body of Christ in Latin, so I want to talk about the Eucharist. A Pew survey of Catholics in 2008 found that 50% of Catholics did not believe in the real presence, that the bread and wine become the Body and Blood of Christ during the Eucharistic Prayer. I was surprised by that at the time, but thought it really cannot be proven scientifically, you have to accept in on faith, so maybe this is something people have a hard time with. Then I read a 2013 study that wanted to investigate this a little further. They asked Catholics different questions. They found that 50% of Catholics said that they did not know what the Catholic Church teaches about the Eucharist. The vast majority of the 50% that knew the Church teaching also believed it. A small percentage of those who reported that they did not know the Church teaching, believed in the real presence. They kind of came to that on their own. This points to a different problem, not that people have a hard time believing the Church teaching but that they do not know the Church teaching. So I want to talk a little about the development of the theology of the Eucharist. Jesus gave us the Eucharist at the Last Supper, and the basis for our belief in the Real Presence if found in the Gospels. Jesus said this is my Body, this is my Blood. Do this in memory of me. He did not say this is like my body and blood; this is symbolic of my body and blood. -

Issue 21 - June 2019

ARCHDIOCESE OF PORTLAND IN OREGON Divine Worship Newsletter Corpus Christi Procession, Bolsena Italy ISSUE 21 - JUNE 2019 Welcome to the twenty first Monthly Newsletter of the Office of Divine Worship of the Archdiocese of Portland in Oregon. We hope to provide news with regard to liturgical topics and events of interest to those in the Archdiocese who have a pastoral role that involves the Sacred Liturgy. The hope is that the priests of the Archdiocese will take a glance at this newsletter and share it with those in their parishes that are involved or interested in the Sacred Liturgy. This Newsletter is now available through Apple Books and always available in pdf format on the Archdiocesan website. It will also be included in the weekly priests’ mailing. If you would like to be emailed a copy of this newsletter as soon as it is published please send your email address to Anne Marie Van Dyke at [email protected]. Just put DWNL in the subject field and we will add you to the mailing list. All past issues of the DWNL are available on the Divine Worship Webpage and from Apple Books. The answer to last month’s competition was St. Paul outside the Walls in Rome - the first correct answer was submitted by Sr. Esther Mary Nickel, RSM of Saginaw, MI. If you have a topic that you would like to see explained or addressed in this newsletter please feel free to email this office and we will try to answer your questions and treat topics that interest you and perhaps others who are concerned with Sacred Liturgy in the Archdiocese. -

A Reflection for the Feast of Corpus Christi 11 June 2020 Father Paul

A Reflection for the Feast of Corpus Christi 11 June 2020 Father Paul Smith The Feast of Corpus Christi (Body of Christ) falls on the Thursday after Trinity Sunday which we celebrate today. While the Church of England refers to it also as the Thanksgiving for the Institution of the Holy Communion, in the Catholic tradition of our church it has greater weight than that; if I can put it in those terms. Indeed, at St Michael’s, it is a significant day, when as we celebrate the Eucharist we make our devotion to the presence of Jesus in the Blessed Sacrament of the Altar. The truth that Jesus is particularly and mysteriously present in the Sacrament is something that we gather both to remember and rejoice in. In the great ‘I am’ sayings of John’s gospel, Jesus says: ‘I am the bread of life’. (John 6.35). Moreover, in the gospel set for today Jesus says: ‘I am the living bread that came down from heaven. Whoever eats of this bread will live for ever, and the bread that I will give for the life of the world is my flesh’. (John 6.51). Herein lay our Eucharistic understanding both to receive Holy Communion, and to adore the presence of Jesus in the Sacrament of the Altar. On this Feast Day there is normally a procession of the Blessed Sacrament around the church. Indeed these processions have gone on in the Roman Catholic Church for centuries, the Feast having been instituted in the year 1246. Processions have not been confined to inside the building, they have gone on in towns and villages throughout our own nation. -

Thought for the Week Thought for the Week Is Based on One of the Day's

Thought for the Week Thought for the Week is based on one of the day’s lectionary readings. For the Bible online, go to: http://bible.oremus.org/ Choose your version (we use NRSV in church) Copy and paste the reference into the search box and the passage will be displayed. Wednesday 2 June Luke 9.11-17 Tomorrow is the feast of Corpus Christi, the body of Christ, which falls on the Thursday after Trinity Sunday. It is celebrated in the Anglican, Roman Catholic and Orthodox churches and dates back to the 13th century. Many countries in the world observe a holiday on Corpus Christi and much festivity takes place with colourful processions through the streets. The consecrated host is carried around with great dignity and awe in a monstrance – a container designed to safely display something of great value. In the UK this generally takes place within or immediately around a church. The idea of this festival seems to have originated with Juliana of Liege, from Belgium, a nun who petitioned for a special feast to celebrate the Eucharist outside the season of Lent. The institution of the Eucharist was already recognised on Maundy Thursday as it is now, but somewhat overshadowed that day by other aspects of the Passion of Christ; the footwashing, the agony in the Garden. Also of course, no festivities would be allowed during Lent. The Corpus Christi feast focussed on the Eucharist alone; and outside of Lent, everyone could ‘go to town’ with the celebrations, a great knees up; a release of energy and joy after the privations of Lent. -

Lauda Sion Salvatorem – Editor’S Notes

Lauda Sion Salvatorem – Editor’s Notes "Lauda Sion Salvatorem" is a sequence prescribed for the Roman Catholic Mass for the Feast of Corpus Christi. The original poem was written by St. Thomas Aquinas around 1264, at the request of Pope Urban IV. The Feast of Corpus Christi (Latin for "Body of Christ") is a Catholic liturgical solemnity celebrating the real presence of the body and blood of Jesus Christ, the Son of God, in the elements of the Eucharist—known as transubstantiation. The feast is liturgically celebrated on the Thursday after Trinity Sunday, which typically falls in mid-June. Hilarión Eslava set this Gregorian chant into a lavish orchestral setting, including two Baritone solos. He also included an organ reduction for use in lieu of the orchestral accompaniment. For purposes of making this a little more accessible to amateur choirs, I chose to also include a poetic English translation in the score, which was not provided in Eslava’s original work. LATIN LYRICS: Lauda Sion Salvatorem, lauda ducem et pastorem, in hymnis et canticis. Quantum potes, tantum aude: quia maior omni laude, nec laudare sufficis. Laudis thema specialis, panis vivus et vitalis hodie proponitur. Quem in sacrae mensa cenae, turbae fratrum duodenae datum non ambigitur. Sit laus plena, sit sonora, sit iucunda, sit decora mentis iubilatio. Dogma datur christianis, quod in carnem transit panis, et vinum in sanguinem. Quod non capis, quod non vides, animosa firmat fides, praeter rerum ordinem. Caro cibus, sanguis potus: manet tamen Christus totus sub utraque specie. Sumit unus, sumunt mille: quantum isti, tantum ille: nec sumptus consumitur.