Dw = Fds = Pads = Pdv W =

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lecture 4: 09.16.05 Temperature, Heat, and Entropy

3.012 Fundamentals of Materials Science Fall 2005 Lecture 4: 09.16.05 Temperature, heat, and entropy Today: LAST TIME .........................................................................................................................................................................................2� State functions ..............................................................................................................................................................................2� Path dependent variables: heat and work..................................................................................................................................2� DEFINING TEMPERATURE ...................................................................................................................................................................4� The zeroth law of thermodynamics .............................................................................................................................................4� The absolute temperature scale ..................................................................................................................................................5� CONSEQUENCES OF THE RELATION BETWEEN TEMPERATURE, HEAT, AND ENTROPY: HEAT CAPACITY .......................................6� The difference between heat and temperature ...........................................................................................................................6� Defining heat capacity.................................................................................................................................................................6� -

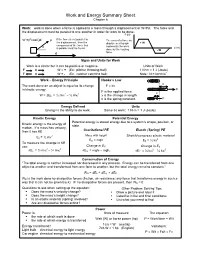

Work and Energy Summary Sheet Chapter 6

Work and Energy Summary Sheet Chapter 6 Work: work is done when a force is applied to a mass through a displacement or W=Fd. The force and the displacement must be parallel to one another in order for work to be done. F (N) W =(Fcosθ)d F If the force is not parallel to The area of a force vs. the displacement, then the displacement graph + W component of the force that represents the work θ d (m) is parallel must be found. done by the varying - W d force. Signs and Units for Work Work is a scalar but it can be positive or negative. Units of Work F d W = + (Ex: pitcher throwing ball) 1 N•m = 1 J (Joule) F d W = - (Ex. catcher catching ball) Note: N = kg m/s2 • Work – Energy Principle Hooke’s Law x The work done on an object is equal to its change F = kx in kinetic energy. F F is the applied force. 2 2 x W = ΔEk = ½ mvf – ½ mvi x is the change in length. k is the spring constant. F Energy Defined Units Energy is the ability to do work. Same as work: 1 N•m = 1 J (Joule) Kinetic Energy Potential Energy Potential energy is stored energy due to a system’s shape, position, or Kinetic energy is the energy of state. motion. If a mass has velocity, Gravitational PE Elastic (Spring) PE then it has KE 2 Mass with height Stretch/compress elastic material Ek = ½ mv 2 EG = mgh EE = ½ kx To measure the change in KE Change in E use: G Change in ES 2 2 2 2 ΔEk = ½ mvf – ½ mvi ΔEG = mghf – mghi ΔEE = ½ kxf – ½ kxi Conservation of Energy “The total energy is neither increased nor decreased in any process. -

Lecture 8: Maximum and Minimum Work, Thermodynamic Inequalities

Lecture 8: Maximum and Minimum Work, Thermodynamic Inequalities Chapter II. Thermodynamic Quantities A.G. Petukhov, PHYS 743 October 4, 2017 Chapter II. Thermodynamic Quantities Lecture 8: Maximum and Minimum Work, ThermodynamicA.G. Petukhov,October Inequalities PHYS 4, 743 2017 1 / 12 Maximum Work If a thermally isolated system is in non-equilibrium state it may do work on some external bodies while equilibrium is being established. The total work done depends on the way leading to the equilibrium. Therefore the final state will also be different. In any event, since system is thermally isolated the work done by the system: jAj = E0 − E(S); where E0 is the initial energy and E(S) is final (equilibrium) one. Le us consider the case when Vinit = Vfinal but can change during the process. @ jAj @E = − = −Tfinal < 0 @S @S V The entropy cannot decrease. Then it means that the greater is the change of the entropy the smaller is work done by the system The maximum work done by the system corresponds to the reversible process when ∆S = Sfinal − Sinitial = 0 Chapter II. Thermodynamic Quantities Lecture 8: Maximum and Minimum Work, ThermodynamicA.G. Petukhov,October Inequalities PHYS 4, 743 2017 2 / 12 Clausius Theorem dS 0 R > dS < 0 R S S TA > TA T > T B B A δQA > 0 B Q 0 δ B < The system following a closed path A: System receives heat from a hot reservoir. Temperature of the thermostat is slightly larger then the system temperature B: System dumps heat to a cold reservoir. Temperature of the system is slightly larger then that of the thermostat Chapter II. -

Entropy: Is It What We Think It Is and How Should We Teach It?

Entropy: is it what we think it is and how should we teach it? David Sands Dept. Physics and Mathematics University of Hull UK Institute of Physics, December 2012 We owe our current view of entropy to Gibbs: “For the equilibrium of any isolated system it is necessary and sufficient that in all possible variations of the system that do not alter its energy, the variation of its entropy shall vanish or be negative.” Equilibrium of Heterogeneous Substances, 1875 And Maxwell: “We must regard the entropy of a body, like its volume, pressure, and temperature, as a distinct physical property of the body depending on its actual state.” Theory of Heat, 1891 Clausius: Was interested in what he called “internal work” – work done in overcoming inter-particle forces; Sought to extend the theory of cyclic processes to cover non-cyclic changes; Actively looked for an equivalent equation to the central result for cyclic processes; dQ 0 T Clausius: In modern thermodynamics the sign is negative, because heat must be extracted from the system to restore the original state if the cycle is irreversible . The positive sign arises because of Clausius’ view of heat; not caloric but still a property of a body The transformation of heat into work was something that occurred within a body – led to the notion of “equivalence value”, Q/T Clausius: Invented the concept “disgregation”, Z, to extend the ideas to irreversible, non-cyclic processes; TdZ dI dW Inserted disgregation into the First Law; dQ dH TdZ 0 Clausius: Changed the sign of dQ;(originally dQ=dH+AdL; dL=dI+dW) dHdQ Derived; dZ 0 T dH Called; dZ the entropy of a body. -

Lecture 6: Entropy

Matthew Schwartz Statistical Mechanics, Spring 2019 Lecture 6: Entropy 1 Introduction In this lecture, we discuss many ways to think about entropy. The most important and most famous property of entropy is that it never decreases Stot > 0 (1) Here, Stot means the change in entropy of a system plus the change in entropy of the surroundings. This is the second law of thermodynamics that we met in the previous lecture. There's a great quote from Sir Arthur Eddington from 1927 summarizing the importance of the second law: If someone points out to you that your pet theory of the universe is in disagreement with Maxwell's equationsthen so much the worse for Maxwell's equations. If it is found to be contradicted by observationwell these experimentalists do bungle things sometimes. But if your theory is found to be against the second law of ther- modynamics I can give you no hope; there is nothing for it but to collapse in deepest humiliation. Another possibly relevant quote, from the introduction to the statistical mechanics book by David Goodstein: Ludwig Boltzmann who spent much of his life studying statistical mechanics, died in 1906, by his own hand. Paul Ehrenfest, carrying on the work, died similarly in 1933. Now it is our turn to study statistical mechanics. There are many ways to dene entropy. All of them are equivalent, although it can be hard to see. In this lecture we will compare and contrast dierent denitions, building up intuition for how to think about entropy in dierent contexts. The original denition of entropy, due to Clausius, was thermodynamic. -

Work-Energy for a System of Particles and Its Relation to Conservation Of

Conservation of Energy, the Work-Energy Principle, and the Mechanical Energy Balance In your study of engineering and physics, you will run across a number of engineering concepts related to energy. Three of the most common are Conservation of Energy, the Work-Energy Principle, and the Mechanical Engineering Balance. The Conservation of Energy is treated in this course as one of the overarching and fundamental physical laws. The other two concepts are special cases and only apply under limited conditions. The purpose of this note is to review the pedigree of the Work-Energy Principle, to show how the more general Mechanical Energy Bal- ance is developed from Conservation of Energy, and finally to describe the conditions under which the Mechanical Energy Balance is preferred over the Work-Energy Principle. Work-Energy Principle for a Particle Consider a particle of mass m and velocity V moving in a gravitational field of strength g sub- G ject to a surface force Rsurface . Under these conditions, writing Conservation of Linear Momen- tum for the particle gives the following: d mV= R+ mg (1.1) dt ()Gsurface Forming the dot product of Eq. (1.1) with the velocity of the particle and rearranging terms gives the rate form of the Work-Energy Principle for a particle: 2 dV⎛⎞ d d ⎜⎟mmgzRV+=() surfacei G ⇒ () EEWK += GP mech, in (1.2) dt⎝⎠2 dt dt Gravitational mechanical Kinetic potential power into energy energy the system Recall that mechanical power is defined as WRmech, in= surfaceiV G , the dot product of the surface force with the velocity of its point of application. -

3. Energy, Heat, and Work

3. Energy, Heat, and Work 3.1. Energy 3.2. Potential and Kinetic Energy 3.3. Internal Energy 3.4. Relatively Effects 3.5. Heat 3.6. Work 3.7. Notation and Sign Convention In these Lecture Notes we examine the basis of thermodynamics – fundamental definitions and equations for energy, heat, and work. 3-1. Energy. Two of man's earliest observations was that: 1)useful work could be accomplished by exerting a force through a distance and that the product of force and distance was proportional to the expended effort, and 2)heat could be ‘felt’ in when close or in contact with a warm body. There were many explanations for this second observation including that of invisible particles traveling through space1. It was not until the early beginnings of modern science and molecular theory that scientists discovered a true physical understanding of ‘heat flow’. It was later that a few notable individuals, including James Prescott Joule, discovered through experiment that work and heat were the same phenomenon and that this phenomenon was energy: Energy is the capacity, either latent or apparent, to exert a force through a distance. The presence of energy is indicated by the macroscopic characteristics of the physical or chemical structure of matter such as its pressure, density, or temperature - properties of matter. The concept of hot versus cold arose in the distant past as a consequence of man's sense of touch or feel. Observations show that, when a hot and a cold substance are placed together, the hot substance gets colder as the cold substance gets hotter. -

Chemistry 130 Gibbs Free Energy

Chemistry 130 Gibbs Free Energy Dr. John F. C. Turner 409 Buehler Hall [email protected] Chemistry 130 Equilibrium and energy So far in chemistry 130, and in Chemistry 120, we have described chemical reactions thermodynamically by using U - the change in internal energy, U, which involves heat transferring in or out of the system only or H - the change in enthalpy, H, which involves heat transfers in and out of the system as well as changes in work. U applies at constant volume, where as H applies at constant pressure. Chemistry 130 Equilibrium and energy When chemical systems change, either physically through melting, evaporation, freezing or some other physical process variables (V, P, T) or chemically by reaction variables (ni) they move to a point of equilibrium by either exothermic or endothermic processes. Characterizing the change as exothermic or endothermic does not tell us whether the change is spontaneous or not. Both endothermic and exothermic processes are seen to occur spontaneously. Chemistry 130 Equilibrium and energy Our descriptions of reactions and other chemical changes are on the basis of exothermicity or endothermicity ± whether H is negative or positive H is negative ± exothermic H is positive ± endothermic As a description of changes in heat content and work, these are adequate but they do not describe whether a process is spontaneous or not. There are endothermic processes that are spontaneous ± evaporation of water, the dissolution of ammonium chloride in water, the melting of ice and so on. We need a thermodynamic description of spontaneous processes in order to fully describe a chemical system Chemistry 130 Equilibrium and energy A spontaneous process is one that takes place without any influence external to the system. -

Discipline in Thermodynamics

energies Perspective Discipline in Thermodynamics Adrian Bejan Department of Mechanical Engineering and Materials Science, Duke University, Durham, NC 27708-0300, USA; [email protected] Received: 24 April 2020; Accepted: 11 May 2020; Published: 15 May 2020 Abstract: Thermodynamics is a discipline, with unambiguous concepts, words, laws and usefulness. Today it is in danger of becoming a Tower of Babel. Its key words are being pasted brazenly on new concepts, to promote them with no respect for their proper meaning. In this brief Perspective, I outline a few steps to correct our difficult situation. Keywords: thermodynamics; discipline; misunderstandings; disorder; entropy; second law; false science; false publishing 1. Our Difficult Situation Thermodynamics used to be brief, simple and unambiguous. Today, thermodynamics is in a difficult situation because of the confusion and gibberish that permeate through scientific publications, popular science, journalism, and public conversations. Thermodynamics, entropy, and similar names are pasted brazenly on new concepts in order to promote them, without respect for their proper meaning. Thermodynamics is a discipline, a body of knowledge with unambiguous concepts, words, rules and promise. Recently, I made attempts to clarify our difficult situation [1–4], so here are the main ideas: The thermodynamics that in the 1850s joined science serves now as a pillar for the broadest tent, which is physics. From Carnot, Rankine, Clausius, and William Thomson (Lord Kelvin) came not one but two laws: the law of energy conservation (the first law) and the law of irreversibility (the second law). The success of the new science has been truly monumental, from steam engines and power plants of all kinds, to electric power in every outlet, refrigeration, air conditioning, transportation, and fast communication today. -

16. the First Law of Thermodynamics

16. The First Law of Thermodynamics Introduction and Summary The First Law of Thermodynamics is basically a statement of Conservation of Energy. The total energy of a thermodynamic system is called the Internal Energy U. A system can have its Internal Energy changed (DU) in two major ways: (1) Heat Q can flow into the system from the surroundings and (2) the system can do work W on the surroundings. The concept of Heat Energy Q has been discussed previously in connection with Specific Heat c and the Latent Heats of fusion and vaporization at phase transitions. Here, we will focus on the Heat Q absorbed or given off by an ideal gas. Also, the Work W done by an ideal gas will be calculated. Both heat and work are energy, and it is important to understand the difference between the heat Q and the work W. Thermodynamic Work W Previously, we understood the concept of Mechanical Work in connection with Newton's Laws of Motion. There the focus was work done ON THE SYSTEM. For example, the work done on a mass M in raising it up a height h against gravity is W=Mgh. Thermodynamic Work is similar to Mechanical Work BUT in Thermodynamic Work the focus is on the work done BY THE SYSTEM. Historically, Thermodynamics was developed in order to understand the work done BY heat engines like the steam engine. So when a system (like a heat engine) does work ON its surroundings, then the Thermodynamic Work is POSITIVE. (This is the opposite for Mechanical Work.) If work is done on the heat engine, the Thermodynamic Work is NEGATIVE. -

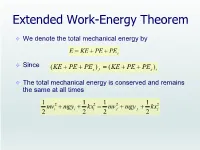

Extended Work-Energy Theorem

Extended Work-Energy Theorem We denote the total mechanical energy by E KE PE PEs Since (KE PE PEs ) f (KE PE PEs )i The total mechanical energy is conserved and remains the same at all times 1 1 1 1 mv 2 mgy kx2 mv 2 mgy kx2 2 i i 2 i 2 f f 2 f A block projected up a incline A 0.5-kg block rests on a horizontal, frictionless surface. The block is pressed back against a spring having a constant of k = 625 N/m, compressing the spring by 10.0 cm to point A. Then the block is released. (a) Find the maximum distance d the block travels up the frictionless incline if θ = 30°. (b) How fast is the block going when halfway to its maximum height? A block projected up a incline Point A (initial state): v 0, y 0, x 10cm 0.1m Point B (final state): i i i v f 0, y f h d sin , x f 0 1 kx2 mgy mgd sin 2 i f 1 1 1 1 mv 2 mgy kx2 mv 2 mgy kx2 2 i i 2 i 2 f f 2 f 1 kx2 0.5(625N / m )( 0.1 m )2 d 2 i mg sin (0.5kg )(9.8 m / s2 )sin30 1.28m A block projected up a incline Point A (initial state): vi 0, yi 0, xi 10cm 0.1m Point B (final state): v f ?, y f h / 2 d sin / 2, x f 0 1 2 1 2 h k 2 2 kxi mv f mg ( ) x v gh 2 2 2 m i f h d sin (1.28m)sin 30 0.64m 1 1 1 1 kmv 2 mgy kx2 mv 2 mgy kx2 v 2 x2i gh i 2 i 2 f f 2 f f m i ..... -

The Second Law and Entropy Misconceptions Demystified

entropy Editorial The Second Law and Entropy Misconceptions Demystified Milivoje M. Kostic Department of Mechanical Engineering, Northern Illinois University, DeKalb, IL 60115, USA; [email protected] Received: 1 June 2020; Accepted: 8 June 2020; Published: 11 June 2020 Abstract: The challenges and claims of hypothetical violations of the Second Law of thermodynamics have been a topic of many scientific, philosophical and social publications, even in the most prestigious scientific journals. Fascination with challenging the Second Law has further accelerated throughout the development of statistical and quantum physics, and information theory. It is phenomenologically reasoned here that non-equilibrium, useful work-energy potential is always dissipated to heat, and thus thermodynamic entropy (a measure of thermal disorder, not any other disorder) is generated always and everywhere, at any scale without exception, including life processes, open systems, micro-fluctuations, gravity or entanglement. Furthermore, entropy cannot be destroyed by any means at any scale (entropy is conserved in ideal, reversible processes and irreversibly generated in real processes), and thus, entropy cannot overall decrease, but only overall increase. Creation of ordered structures or live species always dissipate useful energy and generate entropy, without exception, and thus without Second Law violation. Entropy destruction would imply spontaneous increase in non-equilibrium, with mass-energy flux displacement against cause-and-effect, natural forces, as well as negate the reversible existence of the very equilibrium. In fact, all resolved challengers’ paradoxes and misleading violations of the Second Law to date have been resolved in favor of the Second Law and never against. We are still to witness a single, still open Second Law violation, to be confirmed.