Australian Women's Book Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FEM-Affinity Exhibition Publication Online PDF Here

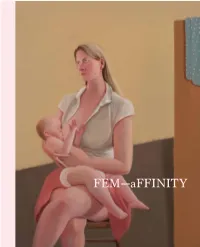

1 — FEM—aFFINITY — 2 FEM—aFFINITY Fulli Andrinopoulos / Jane Trengove Dorothy Berry / Jill Orr Wendy Dawson / Helga Groves Bronwyn Hack / Heather Shimmen Eden Menta / Janelle Low Lisa Reid / Yvette Coppersmith Cathy Staughton / Prudence Flint A NETS Victoria & Arts Project Australia touring exhibition, curated by Catherine Bell Cover Prudence Flint Feed 2019 oil on linen 105 × 90 cm Courtesy of the artist, represented by Australian Galleries, Melbourne BacK Cover Eden Menta & Janelle Low Eden and the Gorge 2019 inkjet print, ed. 1/5 100 × 80 cm Courtesy of the artists; Eden Menta is represented by Arts Project Australia, Melbourne — Co-published by: National Exhibitions Touring Support Victoria c/- The Ian Potter Centre: NGV Australia Federation Square PO Box 7259 Melbourne Vic 8004 netsvictoria.org.au and Arts Project Australia 24 High Street Northcote Vic 3070 artsproject.org.au — Design: Liz Cox, studiomono.co Copyediting & proofreading: Clare Williamson Printer: Ellikon Edition: 1000 ISBN: 978-0-6486691-0-4 Images © the artists 2019. Text © the authors, NETS Victoria and Arts Project Australia 2019. The views and opinions expressed here are those of the authors. No material, whether written or photographic, may be reproduced without the permission of the artists, authors, NETS Victoria and Arts Project Australia. Every effort has been made to ensure that any text and images in this publication have been reproduced with the permission of the artists or the appropriate authorities, wherever it is possible. 3 — Lisa Reid Not titled 2019 -

Download LOOK. LOOK AGAIN Brochure

LOOK. LOOK AGAIN CAMPUS PARTNER LOOK. OUTSKIRTS Outskirts: feminisms along the edge is a feminist cultural studies journal produced through the discipline of Gender Studies at UWA. Published LOOK AGAIN twice yearly, the journal presents new and challenging critical material from a range of disciplinary perspectives and feminist topics, to discuss and contest contemporary and historical issues involving women and feminisms. An initiative of postgraduate students at UWA, Outskirts began as a printed magazine in 1996 before going online in 1998 under the editorship of Delys Bird and then Alison Bartlett since 2006. Outskirts will be publishing selected papers from the symposium Are we there yet? in 2013. GENDER STUDIES Gender Studies is an interdisciplinary area that examines the history and politics of gender relations. Academic staff teach units about the history of ideas of gender, intersections with race, class and sexuality, and the operations of social power. They are also engaged in a range of scholarly research activities around the history and politics of gender relations, sexualities, cinema, maternity, witchcraft, masculinities, activism, intersections of race, class and gender, feminist theory and the body. While some graduates have gone on to specialise in gender- related areas such as equity and diversity, policy development, social justice and workplace relations, most apply their skills in the broader fields of communications, education, public service, research occupations and professional practice. Gender Studies staff are participating in the public programs and symposium associated with this exhibition. LOOK. LOOK AGAIN Above: Sangeeta Sandrasegar, Untitled (Self portrait of Prudence), 2009 felt, glass beads, sequins, cotton, 88 x 60 cm ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Courtesy of the artist The Lawrence Wilson Art Gallery would like to extend sincere thanks to Cover: Nora Heysen, Gladioli, 1933, oil on canvas, 63 x 48.5 cm all the artists whose work is included in this exhibition. -

Marlene Dumas and Autobiography

Kissing the Toad: Marlene Dumas and Autobiography Author Fragar, Julie Published 2013 Thesis Type Thesis (PhD Doctorate) School Queensland College of Art DOI https://doi.org/10.25904/1912/407 Copyright Statement The author owns the copyright in this thesis, unless stated otherwise. Downloaded from http://hdl.handle.net/10072/367588 Griffith Research Online https://research-repository.griffith.edu.au KISSING THE TOAD: Marlene Dumas and Autobiography Julie Fragar MFA Queensland College of Art Griffith University Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. March 2013 i ABSTRACT The work of South African born painter Marlene Dumas has frequently been described as “intimate”, “conversational” and filled with “desire”. Though her work is fiercely material and painterly, and though the majority of her subjects derive from universal mass-media images or art history, a preoccupation with Dumas’ biographical self persists in most interpretations of her work. This thesis considers why this is so. I assert that Dumas’ work engages in a highly self-reflexive mode of authorial presence that is marked by a reference to its own artificiality or contrivance. I argue that, while understandable, simplistic biographical or intentional readings of Dumas’ work are unhelpful, and that Dumas’ authorial presence, more interestingly, questions the nature of authentic communication through art. This argument also suggests that the visual arts require a more nuanced understanding of the authorial self in art than has been evident to date. To demonstrate better critical engagement with the author, I refer to theories from contemporary autobiographical studies that provide a rich language of authorial presence. -

Creativity & Cultural Production in the Hunter

An applied ethnographic study of Creativity & Cultural new entrepreneurial systems in the Production in the Hunter creative industries. �Newcastle THE UNIVER.51TY Of ""IIIIIIINow The University of Newcastle I April 20i9, ARC Grant LP i30i00348 NEWCASTLE AustralianCover11.111r.nt AUSTRALIA •Mlfiii 11. VISUAL ARTS 11.1 A Brief History of Visual Arts in Australia The visual arts in Australia have a very long history. In Rattling Spears: A History of Indigenous Australian Art (2016), Ian McLean indicates that Indigenous communities across the country produced symbolic work that carried meaning for its users for aeons before colonisation saw the paintbrushes of Joseph Lycett and John Glover represent the new settlements and the recent arrival of Europeans. A number of works outline the history of art in Australia (Hughes 1970, Smith 1960, 1979, 1990 and 2000, Sayers 2001, Anderson 2011, Grishin 2013). Christopher Allen in Art in Australia: From Colonization to Postmodernism (1997) sets out the stages he believes Australian Art has progressed through, from the early colonial to high colonial, the Heidelberg School, Federation, Modernism, Abstraction and Social Realism, as seen in the work of the Angry Penguins, Postmodern pluralism and more recently, contemporary art from the 1990s onward. Beginning with Joseph Banks’ illustrations of flora and fauna during Cook’s voyage to Australia, followed by George Stubbs’ ‘Kongouro’ painting in 1772, images of the flora and fauna of the continent entered the consciousness of Europeans. New settler artists, some of them convicted felons, drew and painted their new home, including its indigenous people. Joseph Lycett, for example, painted ‘Corroboree at Newcastle’ in 1818 while John Glover’s ‘Corroboree at Mills Plains’ in 1832 represented life in Van Diemen’s Land. -

In Memory of Doctor Pam Dahl-Helm Johnston

Coolabah, No.14, 2014, ISSN 1988-5946, Observatori: Centre d’Estudis Australians / Australian Studies Centre, Universitat de Barcelona Mapping Our Heartlands: In Memory of Doctor Pam Dahl-Helm Johnston Janie Conway-Herron Copyright© Janie Conway-Herron 2014. This text may be archived and redistributed both in electronic form and in hard copy, provided that the author and journal are properly cited and no fee is charged. Johnston P., 2007. HEARTLANDS: Anatomy of the Human Heart Exhibition, Kendal Gallery in conjunction with Women’s Arts International Festival, Kendal Cumbria My relationship with my heart is close; intimate. I heard it beating before I was born. I have heard it beating all my life. I will hear my last heartbeat as I die. It is what I share with all in the family of humanity (Johnston, P., 2007). When Pam and I finished writing Remembering Ruby – a tribute to author and Bundjalung elder Doctor Ruby Langford Ginibi for a special edition of Coolabah Journal – I had little idea that within six months I would also be mourning my dear friend, fellow academic, artistic colleague and sister in arms, Doctor Pam Johnston. Now, just over a year after her death, I am grateful to have been given the opportunity by Coolabah to edit this special collection of pieces commemorating the extraordinary life and times of Pam Dahl-Helm Johnston. Pam’s life is remarkable for any number of reasons: her inimitable spirit and remarkable resilience in the face of many difficulties is a quality that those close to her will remember well. However it is her achievements as an activist and artist that give us an opportunity to show how the life of this remarkable woman was shaped by the context of her times and the changing discourses of representation, identity and gender politics in the peripatetic cultural landscape of Australia 5 Coolabah, No.14, 2014, ISSN 1988-5946, Observatori: Centre d’Estudis Australians / Australian Studies Centre, Universitat de Barcelona in the 20th and 21st centuries. -

Our Unending Heritage : a Critical Biography Based on the Life of Ella

Our Unending Heritage A critical biography based on the life of Ella Osborn Fry CBE (née Robinson) 1916 – 1997 by Amanda Bell Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the University of Technology Sydney, 2008 Certificate of Authorship/Originality I certify that the work in this thesis has not previously been submitted for a degree nor has it been submitted as part of requirements for a degree except as fully acknowledged within the text. I also certify that the thesis has been written by me. Any help that I have received in my research work and the preparation of the thesis itself has been acknowledged. In addition, I certify that all information sources and literature used are indicated in the thesis. i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to acknowledge some women in particular, who have ensured this thesis came to fruition: Anne Bamford, who encouraged me to commence this project; my supervisor, Rosemary Johnston, who kept me on track with her positive support and guidance; Helen Henderson for her advice and time; Phoebe Scott, a past student of mine and now an art historian in her own right, for her invaluable research assistance; Roberta Rentz, librarian at Brisbane Girls Grammar School, for her willingness to assist and locate reference material; Cherrell Hirst, who has been my mentor since moving to Queensland in 2002 and who has provided positive encouragement throughout this process. I thank the Board of Brisbane Girls Grammar School for its genuine support of the project and finally, my heartfelt thanks to my children, my parents and my best friend, for enduring endless conversations about my writing. -

Karla Dickens Like Many Others Has Spent Time Involved in Green Politics — She Started with Greenpeace Some 30 Years Ago

K ARLA DICKENS ------------------- SOS SOS 20:20 vision blurred vision clear raw sight unknown truths awake a long slow burn No '60s trip hold on to your hat dial a friend the show has began things just got real Some saw their hearts some weep for dollars the air took a deep breath seeds were planted families connected Loved ones die old wounds rise the earth heals 24/7 reports wash your hands Jeffery Pull up your socks be grateful love thy neighbour black lives matter educate yourself The future is now grow hope in your garden eat love feed love be brave SOS S TRAPPED BY THE LOVE OF MONEY 2020 Mixed media Pentaptych , dimensions variable — each component 150 × 66 × 5 cm (approx.) $33,000 S TRAPPED BY THE LOVE OF MONEY I 2020 S TRAPPED BY THE LOVE OF MONEY II 2020 S TRAPPED BY THE LOVE OF MONEY III 2020 S TRAPPED BY THE LOVE OF MONEY IV 2020 S TRAPPED BY THE LOVE OF MONEY V 2020 M ORE OR LESS 2019 Mixed media 87 × 222 cm $19,800 N O SENSE 2020 Mixed media Diptych, dimensions variable — 50 × 34 × 56 cm and 220 × 60 × 3 cm $14,300 N O SENSE 2020—VERSO N O SENSE 2020—DETAIL A S IS 2019 Mixed media 120 × 120 cm $14,300 B LACK JOE' S 2019 Mixed media 120 × 120 cm $14,300 B EFORE YOU GO 2020 Mixed media 120 × 120 cm $14,300 W AR AND ORDER 2020 Mixed media Triptych, dimensions variable — each component 20 × 24 × 28 cm (approx.) $13,200 W AR AND ORDER I 2020 W AR AND ORDER II 2020 W AR AND ORDER III 2020 G AME OVER 2020 Mixed media Pentaptych, dimensions variable — 51 × 25 × 18 cm (largest) $13,200 G AME OVER 2020 — VERSO W E ARE ON FIRE (NOT -

Reinventing Rapport: an Investigation of the Mother/Daughter Dyad Within Contemporary Figure Painting

Reinventing Rapport: An Investigation of the Mother- Daughter Dyad within Contemporary Figure Painting. by Mary Pridmore BA (Hons), Dip Ed, BFA (Hons), University of Tasmania Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Tasmania, February 2008 ii Signed statement of originality This thesis contains no material which has been accepted for a degree or diploma by the University or any other institution. To the best of my knowledge and belief, it incorporates no material previously published or written by another person except where the acknowledgement is made in the text. Mary Pridmore iii Signed statement of authority of access to copying This thesis may be available for loan and limited copying in accordance with the Copyright Act 1968. Mary Pridmore iv Acknowledgements I dedicate the project to the warm, generous and talented women who inspired the project: my mother, Rosemary McGrath, my maternal grandmother, Dame Enid Lyons and my godmother, Mary O’Byrne. I extend special thanks to my supervisor, Paul Zika, for his advice, support and wisdom throughout the course of the project. Thanks are also due to Maria Kunda who gave me valuable advice in the early stages of my reading and encouragement throughout. Thank you to Jennifer Livett and Anne Mestitz for invaluable support through all the stages of the development of this project. For editorial assistance, thanks to Saxby Pridmore, Jennifer Livett and Sandra Champion. Thanks are due to the academic community at the School of Art, post- graduate students and lecturers, and the support staff at the University of Tasmania. -

Striving for National Fitness

STRIVING FOR NATIONAL FITNESS EUGENICS IN AUSTRALIA 1910s TO 1930s Diana H Wyndham A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of History University of Sydney July 1996 Abstract Striving For National Fitness: Eugenics in Australia, 1910s to 1930s Eugenics movements developed early this century in more than 20 countries, including Australia. However, for many years the vast literature on eugenics focused almost exclusively on the history of eugenics in Britain and America. While some aspects of eugenics in Australia are now being documented, the history of this movement largely remained to be written. Australians experienced both fears and hopes at the time of Federation in 1901. Some feared that the white population was declining and degenerating but they also hoped to create a new utopian society which would outstrip the achievements, and avoid the poverty and industrial unrest, of Britain and America. Some responded to these mixed emotions by combining notions of efficiency and progress with eugenic ideas about maximising the growth of a white population and filling the 'empty spaces'. It was hoped that by taking these actions Australia would avoid 'racial suicide' or Asian invasion and would improve national fitness, thus avoiding 'racial decay' and starting to create a 'paradise of physical perfection'. This thesis considers the impact of eugenics in Australia by examining three related propositions: • that from the 1910s to the 1930s, eugenic ideas in Australia were readily accepted because of concerns about the declining birth rate • that, while mainly derivative, Australian eugenics had several distinctly Australian qualities • that eugenics has a legacy in many disciplines, particularly family planning and public health This examination of Australian eugenics is primarily from the perspective of the people, publications and organisations which contributed to this movement in the first half of this century. -

An Australian Woman's Impression and Its Influences

NOTE: Green underlined artist names indicate that a detail biography is provided in Dictionary of Australian Artists. Page 1 Copyright © 2019 David James Angeloro “ An Australian Woman’s Impression and Its Influences ” David James Angeloro “( A More Complete Picture )” by David James Angeloro was born and raised in Syracuse, New York and graduated from Columbia University ( New York City ) and (Excerpt of Draft January 2019) Hobart University ( Geneva ). In 1971, he immigrated to Australia where he has worked as a management- technology consultant for commonwealth-state-local government organisations and large corporations throughout Australasia. David’s interest (obsession) with fine arts started while attending university in New York City. In Australia, he earned a Masters of Art from Sydney University for his thesis Sydney’s Women Sculptors: Women’s Work in Three Dimensions [ 1788-1940 ]. His passion for art extends to art history with particular interests in women artists (his two daughters are well-known artists of mashed-up video works), sculptors and painter-etchers. The Angeloro family collections have been nearly fifty years in the making. David’s collecting philosophy focused on affordable second tier artists, who were generally well- known in their day, but have been ‘forgotten’ by art historians and curators. David has followed the world-wide trend of reassessing the position and value of pre-1940 painters, illustrators, printmakers and sculptors, especially marginalized women artists. Why I’m Selling The Collection ? I’m selling my collection because after nearly fifty years, I’m returning to New York and I don’t want these Australian treasures to be lost and unappreciated. -

Sound Citizens the Public Voices of Australian Women Broadcasters, 1923-1956

SOUND CITIZENS THE PUBLIC VOICES OF AUSTRALIAN WOMEN BROADCASTERS, 1923-1956 Catherine Alison Maree Fisher March 2018 A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The Australian National University © by Catherine Fisher 2018 All Rights Reserved DECLARATION I declare that this thesis is entirely my own original work unless otherwise referenced or acknowledged. Catherine Fisher Date ………………………. …………………. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The process of writing this PhD thesis has been transformative both personally and professionally, and I am grateful to many people. Firstly, I would not have been able to complete this project without the guidance and support of my supervisor, Dr Karen Fox. She is an incredibly kind, dedicated, and conscientious scholar who has always gone above and beyond in her role as my supervisor. Throughout the project she has read and commented on innumerable drafts, been a sounding board for my ideas, and fully supported my career development. It has been a pleasure to work with her for the past three years. My other panel members have also provided me with exceptional support and advice. Professor Angela Woollacott is an inspiring and generous historian who has always believed in me and pushed me to produce the best work possible. Dr Amanda Laugesen has provided regular encouragement and sharp-eyed feedback that has immeasurably improved the final product. Thank you all. I am indebted to the many collections staff who have enabled me to complete this project, especially the collections access staff at the National Film and Sound Archive, Verity Rousset at Murdoch University Archives, and Pamela Barnetta at the National Archives of Australia. -

The Annual Journal and Report of Victorian Women Lawyers ABOUT THIS EDITION of PORTIA

The annual journal and report of Victorian Women Lawyers ABOUT THIS EDITION OF PORTIA THE THEME FOR PORTIA 2019 IS IDEAS AND IDENTITY. THROUGH THIS THEME, WE HAVE EXPLORED INNOVATIVE IDEAS AND IDENTITY POLITICS. ‘Ideas and identity’ draws upon a paradox in recent times, that as technology has enhanced capacity for communication and created a more interconnected world, we are witnessing fractures in people clutching to identity. Whether that be gender, race, sexuality, nationality or religion, there is a real sense that the world is experiencing widening divides. An example is how the recent reforms in New South Wales left South Australia and Western Australia as the only jurisdictions to regulate abortion through the criminal law (a matter currently subject to review of the South Australian Law Reform Institute); but due to the current Religious Discrimination Bill may pose a threat to women in need of such services by prioritising the interests of medical professionals who may conscientiously object. Of course, holding tightly to identity need not widen divides where there is genuine respect and robust debate. Focusing on gender, race, sexuality, nationality or religion and the intersections among them can help us identify who is being left out, and why. Victorian Women Lawyers (VWL) is continuing to bring intersectional issues of diversity and gender into the spotlight through its many events such as the panel discussion on the recent Modern Slavery Act 2018 (Cth) and its impact on slavery and domestic servitude in Australia today. We are glad to report on events like this and to include articles on issues of intersectionality in our Features section.