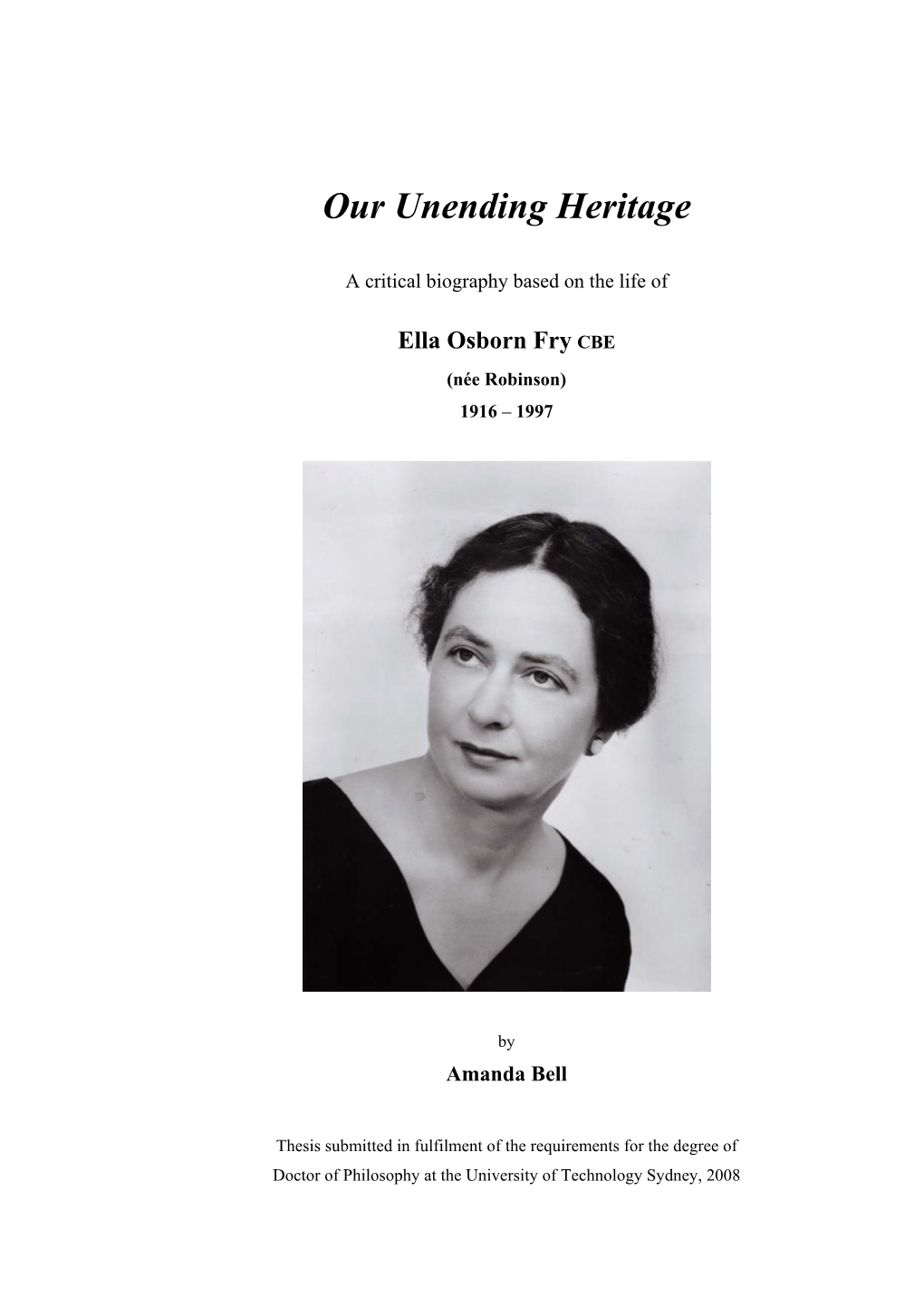

Our Unending Heritage : a Critical Biography Based on the Life of Ella

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

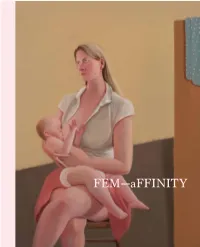

FEM-Affinity Exhibition Publication Online PDF Here

1 — FEM—aFFINITY — 2 FEM—aFFINITY Fulli Andrinopoulos / Jane Trengove Dorothy Berry / Jill Orr Wendy Dawson / Helga Groves Bronwyn Hack / Heather Shimmen Eden Menta / Janelle Low Lisa Reid / Yvette Coppersmith Cathy Staughton / Prudence Flint A NETS Victoria & Arts Project Australia touring exhibition, curated by Catherine Bell Cover Prudence Flint Feed 2019 oil on linen 105 × 90 cm Courtesy of the artist, represented by Australian Galleries, Melbourne BacK Cover Eden Menta & Janelle Low Eden and the Gorge 2019 inkjet print, ed. 1/5 100 × 80 cm Courtesy of the artists; Eden Menta is represented by Arts Project Australia, Melbourne — Co-published by: National Exhibitions Touring Support Victoria c/- The Ian Potter Centre: NGV Australia Federation Square PO Box 7259 Melbourne Vic 8004 netsvictoria.org.au and Arts Project Australia 24 High Street Northcote Vic 3070 artsproject.org.au — Design: Liz Cox, studiomono.co Copyediting & proofreading: Clare Williamson Printer: Ellikon Edition: 1000 ISBN: 978-0-6486691-0-4 Images © the artists 2019. Text © the authors, NETS Victoria and Arts Project Australia 2019. The views and opinions expressed here are those of the authors. No material, whether written or photographic, may be reproduced without the permission of the artists, authors, NETS Victoria and Arts Project Australia. Every effort has been made to ensure that any text and images in this publication have been reproduced with the permission of the artists or the appropriate authorities, wherever it is possible. 3 — Lisa Reid Not titled 2019 -

Our Cultural Collections a Guide to the Treasures Held by South Australia’S Collecting Institutions Art Gallery of South Australia

Our Cultural Collections A guide to the treasures held by South Australia’s collecting institutions Art Gallery of South Australia. South Australian Museum. State Library of South Australia. Car- rick Hill. History SA. Art Gallery of South Aus- tralia. South Australian Museum. State Library of South Australia. Carrick Hill. History SA. Art Gallery of South Australia. South Australian Museum. State Library of South Australia. Car- rick Hill. History SA. Art Gallery of South Aus- Published by Contents Arts South Australia Street Address: Our Cultural Collections: 30 Wakefield Street, A guide to the treasures held by Adelaide South Australia’s collecting institutions 3 Postal address: GPO Box 2308, South Australia’s Cultural Institutions 5 Adelaide SA 5001, AUSTRALIA Art Gallery of South Australia 6 Tel: +61 8 8463 5444 Fax: +61 8 8463 5420 South Australian Museum 11 [email protected] www.arts.sa.gov.au State Library of South Australia 17 Carrick Hill 23 History SA 27 Artlab Australia 43 Our Cultural Collections A guide to the treasures held by South Australia’s collecting institutions The South Australian Government, through Arts South Our Cultural Collections aims to Australia, oversees internationally significant cultural heritage ignite curiosity and awe about these collections comprising millions of items. The scope of these collections is substantial – spanning geological collections, which have been maintained, samples, locally significant artefacts, internationally interpreted and documented for the important art objects and much more. interest, enjoyment and education of These highly valuable collections are owned by the people all South Australians. of South Australia and held in trust for them by the State’s public institutions. -

Art Gallery of South Australia Major Achievements 2003

ANNUAL REPORT of the ART GALLERY OF SOUTH AUSTRALIA for the year 1 July 2003 – 30 June 2004 The Hon. Mike Rann MP, Minister for the Arts Sir, I have the honour to present the sixty-second Annual Report of the Art Gallery Board of South Australia for the Gallery’s 123rd year, ended 30 June 2004. Michael Abbott QC, Chairman Art Gallery Board 2003–2004 Chairman Michael Abbott QC Members Mr Max Carter AO (until 18 January 2004) Mrs Susan Cocks (until 18 January 2004) Mr David McKee (until 20 July 2003) Mrs Candy Bennett (until 18 January 2004) Mr Richard Cohen (until 18 January 2004) Ms Virginia Hickey Mrs Sue Tweddell Mr Adam Wynn Mr. Philip Speakman (commenced 20 August 2003) Mr Andrew Gwinnett (commenced 19 January 2004) Mr Peter Ward (commenced 19 January 2004) Ms Louise LeCornu (commenced 19 January 2004) 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Principal Objectives 5 Major Achievements 2003-2004 6 Issues and Trends 9 Major Objectives 2004–2005 11 Resources and Administration 13 Collections 22 3 APPENDICES Appendix A Charter and Goals of the Art Gallery of South Australia 27 Appendix B1 Art Gallery Board 29 Appendix B2 Members of the Art Gallery of South Australia 29 Foundation Council and Friends of the Art Gallery of South Australia Committee Appendix B3 Art Gallery Organisational Chart 30 Appendix B4 Art Gallery Staff and Volunteers 31 Appendix C Staff Public Commitments 33 Appendix D Conservation 36 Appendix E Donors, Funds, Sponsorships 37 Appendix F Acquisitions 38 Appendix G Inward Loans 50 Appendix H Outward Loans 53 Appendix I Exhibitions and Public Programs 56 Appendix J Schools Support Services 61 Appendix K Gallery Guide Tour Services 61 Appendix L Gallery Publications 62 Appendix M Annual Attendances 63 Information Statement 64 Appendix N Financial Statements 65 4 PRINCIPAL OBJECTIVES The Art Gallery of South Australia’s objectives and functions are effectively prescribed by the Art Gallery Act, 1939 and can be described as follows: • To collect heritage and contemporary works of art of aesthetic excellence and art historical or regional significance. -

Art and Artists in Perth 1950-2000

ART AND ARTISTS IN PERTH 1950-2000 MARIA E. BROWN, M.A. This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The University of Western Australia School of Design Art History 2018 THESIS DECLARATION I, Maria Encarnacion Brown, certify that: This thesis has been substantially accomplished during enrolment in the degree. This thesis does not contain material which has been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma in my name, in any university or other tertiary institution. No part of this work will, in the future, be used in a submission in my name, for any other degree or diploma in any university or other tertiary institution without the prior approval of The University of Western Australia and where applicable, any partner institution responsible for the joint-award of this degree. This thesis does not contain any material previously published or written by another person, except where due reference has been made in the text. The work(s) are not in any way a violation or infringement of any copyright, trademark, patent, or other rights whatsoever of any person. The research involving human data reported in this thesis was assessed and approved by the University of Western Australia Human Research Ethics Committee. Approval # RA/4/1/7748. This thesis does not contain work that I have published, nor work under review for publication. Signature: Date: 14 May 2018 i ABSTRACT This thesis provides an account of the development of the visual arts in Perth from 1950 to 2000 by examining in detail the state of the local art scene at five key points in time, namely 1953, 1962, 1975, 1987 and 1997. -

Down to Earth

Down to Earth 23 MAY - 9 AUGUST 2017 This exhibition of ceramics from the University of Western Australia Art Collection and the Cruthers Collection of Women’s Art, in partnership with the City of Perth Library, is a UWA Away Project. Stewart Scambler, Column, 2013, woodfired stoneware, 37 x 14 cm, The University of Western Australia Art Collection, Gift of the Friends of the Lawrence Wilson Art Gallery, 2013 Guy Grey-Smith, untitled (platter with bobtail lizard design), n.d, hand-painted slip on earthenware, 28 cm, The University of Western Australia Art Collection, Gift of Cherry Lewis, 2014 DOWN TO EARTH Despite originating from different countries, namely Australia, particularly in the sky and tree trunks. Grey-Smith’s untitled work, China and Thailand, the ceramics displayed in Down to Earth are featuring blue/purple bobtail lizards against a harmonious pink intertwined in terms of both the themes that influenced their creators background, again pushes at the boundaries between European and the processes through which they were made. Within this abstraction of form and figurative representation of distinctly exhibition, observable links permeate the ceramics in several ways. Australian subject matter. The use of a hand-painted slip2 to describe Firstly, several of the works represent the local Western Australian the lizards has allowed for a painterly treatment of the subject matter landscape, through visual depiction or through processes that rely and abstraction of form into curvilinear brushstrokes. Juniper’s on local materials. Other Australian ceramists such as Milton Moon untitled ceramic landscape pushes abstraction even further, with a and Joan Campbell have used processes that reflect Zen Buddhism, considered focus on harmonising colour and simplifying forms in a in simplicity and natural asymmetry. -

Download LOOK. LOOK AGAIN Brochure

LOOK. LOOK AGAIN CAMPUS PARTNER LOOK. OUTSKIRTS Outskirts: feminisms along the edge is a feminist cultural studies journal produced through the discipline of Gender Studies at UWA. Published LOOK AGAIN twice yearly, the journal presents new and challenging critical material from a range of disciplinary perspectives and feminist topics, to discuss and contest contemporary and historical issues involving women and feminisms. An initiative of postgraduate students at UWA, Outskirts began as a printed magazine in 1996 before going online in 1998 under the editorship of Delys Bird and then Alison Bartlett since 2006. Outskirts will be publishing selected papers from the symposium Are we there yet? in 2013. GENDER STUDIES Gender Studies is an interdisciplinary area that examines the history and politics of gender relations. Academic staff teach units about the history of ideas of gender, intersections with race, class and sexuality, and the operations of social power. They are also engaged in a range of scholarly research activities around the history and politics of gender relations, sexualities, cinema, maternity, witchcraft, masculinities, activism, intersections of race, class and gender, feminist theory and the body. While some graduates have gone on to specialise in gender- related areas such as equity and diversity, policy development, social justice and workplace relations, most apply their skills in the broader fields of communications, education, public service, research occupations and professional practice. Gender Studies staff are participating in the public programs and symposium associated with this exhibition. LOOK. LOOK AGAIN Above: Sangeeta Sandrasegar, Untitled (Self portrait of Prudence), 2009 felt, glass beads, sequins, cotton, 88 x 60 cm ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Courtesy of the artist The Lawrence Wilson Art Gallery would like to extend sincere thanks to Cover: Nora Heysen, Gladioli, 1933, oil on canvas, 63 x 48.5 cm all the artists whose work is included in this exhibition. -

National Portrait Gallery of Australia Annual Report 13/14

National Portrait Gallery of Australia Annual Report 13/14 National Portrait Gallery of Australia Annual Report 13/14 © National Portrait Gallery of Australia 2014 issn 2204-0811 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical (including photocopying, recording or any information storage and retrieval system), without permission from the publisher. This report is also accessible on the National Portrait Gallery’s website portrait.gov.au National Portrait Gallery King Edward Terrace Canberra, Australia Telephone (02) 6102 7000 portrait.gov.au 24 September 2014 Senator the Hon George Brandis qc Attorney-General Minister for the Arts Parliament House CANBERRA ACT 2600 Dear Minister On behalf of the National Portrait Gallery of Australia Board, I am pleased to submit the Gallery’s first independent annual report for presentation to each House of Parliament. The report covers the period 1 July 2013 to 30 June 2014. This report is submitted in accordance with the National Portrait Gallery of Australia Act, 2012 and the Commonwealth Authorities and Companies Act, 1997. The Performance Report has been prepared according to the Commonwealth Authorities (Annual Reporting) Orders 2011. The financial statements were prepared in line with the Finance Minister’s Orders made under the Commonwealth Authorities and Companies Act, 1997. Yours sincerely Dr Helen Nugent ao Chairman national portrait gallery of australia annual report 2013/14 i Contents Chairman’s letter 3 Director’s report 7 Agency overview 13 Accountability and management 17 Performance summary 23 Report against corporate plan 27 Financial statements 49 Appendices 1. -

Collection Name: Ella Fry Collection of Photographs Collection Number: BA1362

Pictorial collection name: Ella Fry Collection of photographs Collection number: BA1362 Collection Item Photographer Description No. No. BA1362/ 1 Personal Ella [A toddler dressed in romper suit and hat] BA1362/ 2 Murray of Brisbane Ella [A toddler in a dress, holding a doll, seated and Gympie on large chair] BA1362/ 3 Personal Ella [A toddler seated on a rug, holding a doll, pram in background] BA1362/ 4 Personal Ella [A small child in dress and hat, holding a doll, seated on bench BA1362/ 5 Personal Ella [A small child in garden] BA1362/ 6 Personal Ella [A small child standing on verandah feeding a horse BA1362/ 7 Personal Ella [A small child in skirt, jumper, shoes and socks, glasses, seated on cane chair, reading BA1362/ 8 Personal Ella and Mother [A small girl wearing skirt, ,jumper, shoes and socks, glasses and huge bow in hair. Woman wearing long suit seated on chair] BA1362/ 9 Personal Father and Ella [Man in 3 piece suit and hat, girl in short dress, dark stockings, hat. Both standing in paddock, picnickers in background] BA1362/ 10 Personal Grandfather Angus, Father, Ella, Mel, Peter Angus, Donald Angus, Gran, Barbara Angus, Mother [family group] BA1362/ 11 Personal Grandfather and Gran Angus [Both dressed in best clothes] BA1362/ 12 Personal Ella and Mother [Woman in long skirt, jacket and hat, girl in dress and hat, standing in front of tree] BA1362/ 13 The Leicagraph Co Gran and Mother [Both women in long coats Sydney with fur collars and hats, walking down a city street] BA1362/ 14 Personal Gran, Grandfather, Mother [3 people at the beach, seated, leaning on rowing boat. -

Important Australian Art Sydney | 26 June 2019

Important Australian Art Sydney | 26 June 2019 Important Australian Art Sydney | Wednesday 26 June 2019 at 6pm MELBOURNE VIEWING BIDS ENQUIRIES PHYSICAL CONDITION Como House Online bidding will be available Merryn Schriever - Director OF LOTS IN THIS AUCTION Williams Rd & Lechlade Ave for the auction. For further Australian and International Art PLEASE NOTE THAT THERE South Yarra VIC 3141 information please visit: Specialist IS NO REFERENCE IN THIS www.bonhams.com +61 (0) 414 846 493 mob CATALOGUE TO THE PHYSICAL Friday 14 – Sunday 16 June [email protected] CONDITION OF ANY LOT. 10am – 5pm All bidders are advised to INTENDING BIDDERS MUST read the important information Alex Clark SATISFY THEMSELVES AS SYDNEY VIEWING on the following pages relating Australian and International Art TO THE CONDITION OF ANY 36 – 40 Queen St to bidding, payment, collection, Specialist LOT AS SPECIFIED IN CLAUSE Woollahra NSW 2025 and storage of any purchases. +61 (0) 413 283 326 mob 14 OF THE NOTICE TO [email protected] BIDDERS CONTAINED AT THE Friday 21 – Tuesday 25 June REGISTRATION END OF THIS CATALOGUE. 10am – 5pm IMPORTANT NOTICE Francesca Cavazzini Please note that all customers, Aboriginal and International Art As a courtesy to intending AUCTION irrespective of any previous Art Specialist bidders, Bonhams will provide a 36 - 40 Queen Street activity with Bonhams, are +61 (0) 416 022 822 mob written indication of the physical Woollahra NSW 2025 required to complete the Bidder francesca.cavazzini@bonhams. condition of lots in this sale if a Registration Form in advance of com request is received up to 24 Wednesday 26 June at 6pm the sale. -

Grant Recipient Granted Amount Grant Purpose

Grants approved in 2013/14: grant recipient Granted Amount Grant purpose (Connecting Communities) CC Home Care 2,500 To provide essential equipment to assist an individual with a physical disability in making their first transition into Incorporated independent living. 11th Battalion Living History Unit Inc 8,661 Towards historical uniforms to support the commemoration of the Anzac Centenary period. Aboriginal Communities Charitable Organization, 5,000 To support people experiencing financial hardship. Inc Aboriginal Health Council of Western Australia 60,000 Towards a study into the optimal provision of community health services to remote areas of Western Australia. Aboriginal Health Council of Western Australia 2,000,000 Towards the purchase of the new premises for this state wide organisation supporting Aboriginal health services across the Western A ustralia. Abortion Grief Australia Inc 54,621 Towards office equipment to support mental health and wellbeing services for people impacted by abortion. Academic Clinics for Exceptional Students (Inc) 15,000 Towards information technology to improve the educational services for people with a learning disabilities on low incomes. Activ Foundation Incorporated 24,457 Towards minor modifications and equipment for 12 vehicles used to transport people with intellectual disabilities to enable them to participate in the community. Active Greening Inc 17,581 To support the delivery of community activities and events within the Perth Metropolitan area, that aim to connect community with nature and encourage a sense of belonging. AdoptASchool Association Inc 14,625 Towards organisational development that will support active volunteerism in WA. Adoption Support for Families and Children Inc 4,820 Towards a camp to be held in October for children and families. -

Marlene Dumas and Autobiography

Kissing the Toad: Marlene Dumas and Autobiography Author Fragar, Julie Published 2013 Thesis Type Thesis (PhD Doctorate) School Queensland College of Art DOI https://doi.org/10.25904/1912/407 Copyright Statement The author owns the copyright in this thesis, unless stated otherwise. Downloaded from http://hdl.handle.net/10072/367588 Griffith Research Online https://research-repository.griffith.edu.au KISSING THE TOAD: Marlene Dumas and Autobiography Julie Fragar MFA Queensland College of Art Griffith University Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. March 2013 i ABSTRACT The work of South African born painter Marlene Dumas has frequently been described as “intimate”, “conversational” and filled with “desire”. Though her work is fiercely material and painterly, and though the majority of her subjects derive from universal mass-media images or art history, a preoccupation with Dumas’ biographical self persists in most interpretations of her work. This thesis considers why this is so. I assert that Dumas’ work engages in a highly self-reflexive mode of authorial presence that is marked by a reference to its own artificiality or contrivance. I argue that, while understandable, simplistic biographical or intentional readings of Dumas’ work are unhelpful, and that Dumas’ authorial presence, more interestingly, questions the nature of authentic communication through art. This argument also suggests that the visual arts require a more nuanced understanding of the authorial self in art than has been evident to date. To demonstrate better critical engagement with the author, I refer to theories from contemporary autobiographical studies that provide a rich language of authorial presence. -

Sample Chapter

EIGHT: WAR AND LOVE Father didn’t approve of me going to war. He said I would see terrible things I would never forget. – Nora Heysen1 In September 1943 Australian and American forces launched a major offensive in New Guinea against the Japanese in an attempt to halt its army’s rapid southern advance and the imminent threat it posed to Australia.2 After World War I, the League of Nations under the Treaty of Versailles allocated German territories in the region to the victorious Allies. By 1921 Australia had received a formal mandate from the British government to administer the country as a territory of Australia, includ ing the northeast corner of the island formerly German New Guinea. The suspension of this mandate occurred when the Japanese invasion of New Guinea took place in December 1941. By this time Australians were facing the real possibility of the Japanese on their own shores. The proximity of New Guinea to Australia’s northern coast made the unthinkable feasible. In 1942, prior to the combined forces’ arrival, young and undertrained Australian units3 had struggled against the Japanese and the diabolical impact of tropical diseases, most detrimentally malaria, and dengue fever and scrub typhus. The deployment of the joint forces numbering tens of thousands led by US General Douglas MacArthur and Australia’s General Thomas Blamey eventually won back large tracts of territory from the Japanese. According to Australian War Memorial records this was the ‘springboard’4 for MacArthur’s successful advance into the Netherlands East Indies and the Philippines. The Japanese sustained enormous losses against the comparatively wellequipped and resupplied Allied forces supported by air and sea drops: Between March 1943 and April 1944, some 1,200 Australians were killed, and an estimated 35,000 Japanese died.